Robocop Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL SELEZIONE UFFICIALE 2006 Un Film Di PAUL VERHOEVEN UN KOLOSSAL BELLICO in CUI SUCCEDE DAVVERO OGNI COSA

presenta un film di PAUL VERHOEVEN TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL SELEZIONE UFFICIALE 2006 un film di PAUL VERHOEVEN UN KOLOSSAL BELLICO IN CUI SUCCEDE DAVVERO OGNI COSA. RITMO DA GRAN SPETTACOLO DI VITA E MORTE. (CORRIERE DELLA SERA) MOLTO SPETTACOLARE (LA STAMPA) GIRATO BENISSIMO, GRANDE RITMO, NON ANNOIA MAI (IL MESSAGGERO) IMMAGINI FORTI E DI GRANDE VALORE FIGURATIVO (IL TEMPO) TRADIZIONALE E INNOVATIVO. BELLO. (IL GIORNALE) VERHOEVEN AUTENTICA FORZA VISIONARIA (IL MANIFESTO) 10 MINUTI DI APPLAUSI AL FESTIVAL DI VENEZIA PREMIO ARCA CINEMAGIOVANI MIGLIOR FILM Dutch Film Festival PREMIO MIGLIOR FILM PREMIO MIGLIOR REGISTA PREMIO MIGLIORE ATTRICE Platinum Award MASSIMO CAMPIONE DI INCASSI IN OLANDA Oscar 2007 MIGLIOR FILM STRANIERO CANDIDATO UFFICIALE PER L’ OLANDA CAST ARTISTICO RachelSteinn/Ellis De Vries CARICE VAN HOUTEN Ludwig Müntze SEBASTIAN KOCH Hans Akkermans THOM HOFFMAN Ronnie HALINA REIJN Ufficiale Franken WALDEMAR KOBUS Gerben Kuipers DEREK DE LINT GeneraleSS Käutner CHRISTIAN BERKEL VanGein PETER BLOK Rob MICHIEL HUISMAN Tim Kuipers RONALD ARMBRUST voci italiane RachelSteinn/Ellis De Vries CHIARA COLIZZI Ludwig Müntze LUCA WARD Hans Akkermans MASSIMO LODOLO Ronnie LAURA BOCCANERA Ufficiale Franken MASSIMO CORVO Gerben Kuipers GINO LA MONICA dialoghi e direzione del doppiaggio MASSIMO CORVO stabilimento di doppiaggio TECHNICOLOR SOUND SERVICES CAST TECNICO regia: PAUL VERHOEVEN storia originale: GERARD SOETEMAN sceneggiatura: GERARD SOETEMAN direttore della fotografia: PAUL VERHOEVEN luci: KARLWALTER LINDENLAUB, ACS, -

D5310 DIE HARD (USA, 1988) (Other Titles: Piege De Cristal; Stirb Langsam; Trappola Di Cristallo)

D5310 DIE HARD (USA, 1988) (Other titles: Piege de cristal; Stirb langsam; Trappola di cristallo) Credits: director, John McTiernan ; writers, Jeb Stuart, Steven E. de Souza ; story, Roderick Thorp. Cast: Bruce Willis, Bonnie Bedelia, Reginald Veljohnson, Robert Davi, Grand L. Bush. Summary: Action/adventure film set in contemporary Los Angeles. A team of terrorists thieves has seized an office building in L.A. and taken hostages. A New York cop (Willis), in town to spend Christmas with his estranged wife (Bedelia), is the only hope for the people held by the thieves. Two FBI agents assigned to the case (Davi and Bush) are Vietnam veterans. Ansen, David. “The arts: movies: reactivating action heroes” Newsweek 112 (Jul 25, 1988), p. 58. [Reprinted in Film review annual 1989] Breuning, Ulrich. “Die hard” Levenede billeder 5 (Feb 1989), p. 46-7. Broesky, Pat H. “Death is hard ... reincarnation is easy” New York times 143 (Jun 12, 1994), sec. 2, p. 15. Canby, Vincent. “Film view: ‘Die hard’ calls to the kidult” New York times 137 (Jul 31, 1988), sec. 2, p. 19-20. Carr, Jay. “Bruce Willis’ ‘Die hard’: Stylized terror” Boston globe (Jul 15, 1988), p. 29. _______. “Star Bonnie Bedelia keeping her cool” Boston globe (Jul 21, 1988), Calendar, p. 9. Cherchi Usai, Paolo. “Trappola di cristallo” Segnocinema 36 (Jan 1989), p. 26-7. Chiacchiari, Federico. “Trappola di cristallo” Cineforum 28/278 (Oct 1988), p. 92-3. Cieutat, Michel. “Piege de cristal” Positif 334 (Dec 1988), p. 73. Combs, Richard. “Die hard” Monthly film bulletin 56 (Feb 1989), p. 45-6. -

Ficha-Interfaces-Imaginadas-Robocop.Pdf

Proyecto de Innovación Docente Interacción Persona-Ordenador 3º Grado en Ingeniería Informática 2017 Universidad de Salamanca RoboCop (1987) Robocop (título original) Análisis realizado por: Víctor Barrueco Gutiérrez Datos de producción Director: Paul Vernoeven Guionista: Edward Neumeier & Michael Miner Tipo: Película Duración: 103min Ficha en IMDB: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0093870/ Sinopsis [Breve descripción de la historia que se cuenta] se propone un futuro no muy lejano en la ciudad de Detroit, una ciudad llena de delincuencia. Murphy un agente de policía muere en acto de servicio. Para acabar con el crimen se aprueba la creación de un nuevo agente híbrido entre humano y maquina para el cual se usa los restos de Murphy. Necesidades [Análisis de las necesidades de usuario que propician la propuesta de las interfaces] En la película se ven una gran cantidad de tecnologías mayormente orientadas al uso militar y formas de acabar con la delincuencia de forma agresiva. En ella vemos varias necesidades tanto en forma física (hardware) como software. A continuación, se enumeran los principales dispositivos (tecnología ¡/interfaz) que aparecen en la película junto a las tareas de usuario que permiten realizar. Primera Necesidades aparición Controles visuales y sonido 0:10:30 En la película aparece un robot militar cuyo fin es repeler la resistencia. Al detector una amenaza (de foma visual) lanza una advertencia al objetivo. En la película se muestra como falla el reconocimiento de sonido al no ser capaz de reconocer el ruido que Enlace al clip: hace la pistolaal caer. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TstteJ1eIZg 2 Primera Necesidades aparición Sintetizador de voz 0:10:45 Al igual que en el gadget anterior, este aparece por primera vez en el ED 209. -

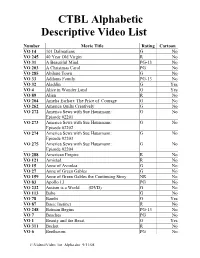

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List Number Movie Title Rating Cartoon VO 14 101 Dalmatians G No VO 245 40 Year Old Virgin R No VO 31 A Beautiful Mind PG-13 No VO 203 A Christmas Carol PG No VO 285 Abilene Town G No VO 33 Addams Family PG-13 No VO 32 Aladdin G Yes VO 4 Alice in Wonder Land G Yes VO 89 Alien R No VO 204 Amelia Earhart: The Price of Courage G No VO 262 America Quilts Creatively G No VO 272 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2201 VO 273 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2202 VO 274 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2203 VO 275 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2204 VO 288 American Empire R No VO 121 Amistad R No VO 15 Anne of Avonlea G No VO 27 Anne of Green Gables G No VO 159 Anne of Green Gables the Continuing Story NR No VO 83 Apollo 13 PG No VO 232 Autism is a World (DVD) G No VO 113 Babe G No VO 78 Bambi G Yes VO 87 Basic Instinct R No VO 248 Batman Begins PG-13 No VO 7 Beaches PG No VO 1 Beauty and the Beast G Yes VO 311 Becket R No VO 6 Beethoven PG No J:\Videos\Video_list_Alpha.doc 9/11/08 VO 160 Bells of St. Mary’s NR No VO 20 Beverly Hills Cop R No VO 79 Big PG No VO 163 Big Bear NR No VO 289 Blackbeard, The Pirate R No VO 118 Blue Hawaii NR No VO 290 Border Cop R No VO 63 Breakfast at Tiffany's NR No VO 180 Bridget Jones’ Diary R No VO 183 Broadcast News R No VO 254 Brokeback Mountain R No VO 199 Bruce Almighty Pg-13 No VO 77 Butch Cassidy and the Sun Dance Kid PG No VO 158 Bye Bye Blues PG No VO 164 Call of the Wild PG No VO 291 Captain Kidd R No VO 94 Casablanca -

Bachelorarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hochschulschriftenserver der Hochschule Mittweida BACHELORARBEIT Frau Annett Petzold Digital Effects in Spielfilmen 2016 Fakultät Medien BACHELORARBEIT Digital Effects in Spielfilmen Autor: Frau Annett Petzold Studiengang: Medientechnik (Ba. Eng.) Seminargruppe: MT12F-B Erstprüfer: Professor Doktor-Ingenieur Robert J. Wierzbicki Zweitprüfer: Master of Science Rika Fleck Einreichung: Mittweida, 08.01.2016 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS Digital Effects in Feature Films author: Ms. Annett Petzold course of studies: Media Engineering seminar group: MT12F-B first examiner: Professor Doctor-Engineer Robert J. Wierzbicki second examiner: Master of Science Rika Fleck submission: Mittweida, 08.01.2016 IV Bibliografische Angaben: Nachname, Vorname: Digital Effects in Spielfilmen: Werden Spezialeffekte in Zukunft nur noch digital umgesetzt? Digital Effects in Feature Films: Are there going to be only computer- generated effects in the future? 2016 - 69 Seiten Mittweida, Hochschule Mittweida (FH), University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2016 Abstract Ziel dieser Arbeit ist es, den aktuellen Einsatz von Filmeffekten im Spielfilmbereich zu untersuchen und mit Hilfe der Ergebnisse auf zukünftige Entwicklungen zu schließen. Im Fokus des Forschungsinteresses steht dabei die Frage, ob Digital Effects das Potential besitzen, den Gebrauch traditioneller Special Effects auf lange Sicht in Spielfilmproduktionen zu ersetzen. Diese Untersuchungen -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

Full Text (PDF)

Document generated on 09/29/2021 9:46 a.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Quand ER est visité par QT Sylvie Gendron L’État du cinéma en salles au Québec Number 179, July–August 1995 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/49640ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Gendron, S. (1995). Review of [Quand ER est visité par QT]. Séquences, (179), 56–57. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 1995 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Télévision qualités qu'il avait perdues sur cassette. Sur la bande-son, les fréquences aiguës sont mieux cali brées, tandis que les basses retrouvent leur impact premier (on peut parfaitement distinguer chacun des pas pneumatiques de RoboCop et on s'étonne de vant la puissance effrayante de son rival, ED-209). Sur les pistes analogiques, on peut entendre tout au long du film les commentaires du réalisateur Paul Verhoeven, du scénariste Edward Neumeier et du producteur Jon Davison. Les anecdotes racontées par Neumeier se révèlent fascinantes et enri chissantes, mais il faut entendre le charmant accent de Verhoeven (il est hollandais d'origine, RoboCop étant son premier film américain) qui s'enthousiasme et s'excite encore aujourd'hui pour le projet. -

ASC History Timeline 1919-2019

American Society of Cinematographers Historical Timeline DRAFT 8/31/2018 Compiled by David E. Williams February, 1913 — The Cinema Camera Club of New York and the Static Camera Club of America in Hollywood are organized. Each consists of cinematographers who shared ideas about advancing the art and craft of moviemaking. By 1916, the two organizations exchange membership reciprocity. They both disband in February of 1918, after five years of struggle. January 8, 1919 — The American Society of Cinematographers is chartered by the state of California. Founded by 15 members, it is dedicated to “advancing the art through artistry and technological progress … to help perpetuate what has become the most important medium the world has known.” Members of the ASC subsequently play a seminal role in virtually every technological advance that has affects the art of telling stories with moving images. June 20, 1920 — The first documented appearance of the “ASC” credential for a cinematographer in a theatrical film’s titles is the silent western Sand, produced by and starring William S. Hart and shot by Joe August, ASC. November 1, 1920 — The first issue of American Cinematographer magazine is published. Volume One, #1, consists of four pages and mostly reports news and assignments of ASC members. It is published twice monthly. 1922 — Guided by ASC members, Kodak introduced panchromatic film, which “sees” all of the colors of the rainbow, and recorded images’ subtly nuanced shades of gray, ranging from the darkest black to the purest white. The Headless Horseman is the first motion picture shot with the new negative. The cinematographer is Ned Van Buren, ASC. -

Artist Catalogue

NOBODY, NOWHERE THE LAST MAN (1805) THE END OF THE WORLD (1916) END OF THE WORLD (1931) DELUGE (1933) THINGS TO COME (1936) PEACE ON EARTH (1939) FIVE (1951) WHEN WORLDS COLLIDE (1951) THE WAR OF THE WORLDS (1953) ROBOT MONSTER (1953) DAY THE WORLD ENDED (1955) KISS ME DEADLY (1955) FORBIDDEN PLANET (1956) INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS (1956) WORLD WITHOUT END (1956) THE LOST MISSILE (1958) ON THE BEACH (1959) THE WORLD, THE FLESH AND THE DEVIL (1959) THE GIANT BEHEMOTH (1959) THE TIME MACHINE (1960) BEYOND THE TIME BAR- RIER (1960) LAST WOMAN ON EARTH (1960) BATTLE OF THE WORLDS (1961) THE LAST WAR (1961) THE DAY THE EARTH CAUGHT FIRE (1961) THE DAY OF THE TRIFFIDS (1962) LA JETÉE (1962) PAN- IC IN YEAR ZERO! (1962) THE CREATION OF THE HUMANOIDS (1962) THIS IS NOT A TEST (1962) LA JETÉE (1963) FAIL-SAFE (1964) WHAT IS LIFE? THE TIME TRAVELERS (1964) THE LAST MAN ON EARTH (1964) DR. STRANGELOVE OR: HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE BOMB (1964) THE DAY THE EARTH CAUGHT FIRE (1964) CRACK IN THE WORLD (1965) DALEKS – INVASION EARTH: 2150 A.D. (1966) THE WAR GAME (1965) IN THE YEAR 2889 (1967) LATE AUGUST AT THE HOTEL OZONE (1967) NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (1968) PLANET OF THE APES (1968) THE BED-SITTING ROOM (1969) THE SEED OF MAN (1969) COLOSSUS: THE FORBIN PROJECT (1970) BE- NEATH THE PLANET OF THE APES (1970) NO BLADE OF GRASS (1970) GAS-S-S-S (1970) THE ANDROM- EDA STRAIN (1971) THE OMEGA MAN (1971) GLEN AND RANDA (1971) ESCAPE FROM THE PLANET OF THE APES (1971) SILENT RUNNING (1972) DO WE HAVE FREE WILL? BEWARE! THE BLOB (1972) -

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven Limited Edition Blu-ray release (2-disc set) on 2 December 2019 From legendary filmmaker Paul Verhoeven (Robocop, Basic Instinct) and screenwriter Gerard Soeteman (Soldier of Orange) comes an explosive, fast-paced and thrilling coming- of-age drama. Raw, intense and unabashedly sexual, Spetters is a wild ride that will knock the unsuspecting for a loop. Starring Renée Soutendijk, Jeroen Krabbé (The Fugitive) and the late great Rutger Hauer (Blade Runner), this limited edition 2-disc set (1 x Blu-ray & 1 x DVD) brings Spetters to Blu-ray for the first time in the UK and is a must own release, packed with over 4 hours of bonus content. In Spetters, three friends long for better lives and see their love of motorcycle racing as a perfect way of doing it. However the arrival of the beautiful and ambitious Fientje threatens to come between them. Special features Remastered in 4K and presented in High Definition for the first time in the UK Audio commentary by director Paul Verhoeven Symbolic Power, Profit and Performance in Paul Verhoeven’s Spetters (2019, 17 mins): audiovisual essay written and narrated by Amy Simmons Andere Tijden: Spetters (2002, 29 mins): Dutch TV documentary on the making of Spetters, featuring the filmmakers, cast and critics of the film Speed Crazy: An Interview with Paul Verhoeven (2014, 8 mins) Writing Spetters: An Interview with Gerard Soeteman (2014, 11 mins) An Interview with Jost Vacano (2014, 67 mins): wide ranging interview with the film’s cinematographer discussing his work on films including Soldier of Orange and Robocop Image gallery Trailers Illustrated booklet (***first pressing only***) containing a new interview with Paul Verhoeven by the BFI’s Peter Stanley, essays by Gerard Soeteman, Rob van Scheers and Peter Verstraten, a contemporary review, notes on the extras and film credits Product details RRP: £22.99 / Cat.