The Life of Sir Henry (Harry) Gullett 1878

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GP Text Paste Up.3

FACING ASIA A History of the Colombo Plan FACING ASIA A History of the Colombo Plan Daniel Oakman Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/facing_asia _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry Author: Oakman, Daniel. Title: Facing Asia : a history of the Colombo Plan / Daniel Oakman. ISBN: 9781921666926 (pbk.) 9781921666933 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Economic assistance--Southeast Asia--History. Economic assistance--Political aspects--Southeast Asia. Economic assistance--Social aspects--Southeast Asia. Dewey Number: 338.910959 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Emily Brissenden Cover: Lionel Lindsay (1874–1961) was commissioned to produce this bookplate for pasting in the front of books donated under the Colombo Plan. Sir Lionel Lindsay, Bookplate from the Australian people under the Colombo Plan, nla.pic-an11035313, National Library of Australia Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press First edition © 2004 Pandanus Books For Robyn and Colin Acknowledgements Thank you: family, friends and colleagues. I undertook much of the work towards this book as a Visiting Fellow with the Division of Pacific and Asian History in the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University. There I benefited from the support of the Division and, in particular, Hank Nelson and Donald Denoon. -

General Sir William Birdwood and the AIF,L914-1918

A study in the limitations of command: General Sir William Birdwood and the A.I.F.,l914-1918 Prepared and submitted by JOHN DERMOT MILLAR for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales 31 January 1993 I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of advanced learning, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. John Dermot Millar 31 January 1993 ABSTRACT Military command is the single most important factor in the conduct of warfare. To understand war and military success and failure, historians need to explore command structures and the relationships between commanders. In World War I, a new level of higher command had emerged: the corps commander. Between 1914 and 1918, the role of corps commanders and the demands placed upon them constantly changed as experience brought illumination and insight. Yet the men who occupied these positions were sometimes unable to cope with the changing circumstances and the many significant limitations which were imposed upon them. Of the World War I corps commanders, William Bird wood was one of the longest serving. From the time of his appointment in December 1914 until May 1918, Bird wood acquired an experience of corps command which was perhaps more diverse than his contemporaries during this time. -

Major General James Harold CANNAN CB, CMG, DSO, VD

Major General James Harold CANNAN CB, CMG, DSO, VD [1882 – 1976] Major General Cannan is distinguished by his service in the Militia, as a senior officer in World War 1 and as the Australian Army’s Quartermaster General in World War 2. Major General James Harold Cannan, CB, CMG, DSO, VD (29 August 1882 – 23 May 1976) was a Queenslander by birth and a long-term member of the United Service Club. He rose to brigadier general in the Great War and served as the Australian Army’s Quartermaster General during the Second World War after which it was said that his contribution to the defence of Australia was immense; his responsibility for supply, transport and works, a giant-sized burden; his acknowledgement—nil. We thank the History Interest Group and other volunteers who have researched and prepared these Notes. The series will be progressively expanded and developed. They are intended as casual reading for the benefit of Members, who are encouraged to advise of any inaccuracies in the material. Please do not reproduce them or distribute them outside of the Club membership. File: HIG/Biographies/Cannan Page 1 Cannan was appointed Commanding Officer of the 15th Battalion in 1914 and landed with it at ANZAC Cove on the evening of 25 April 1915. The 15th Infantry Battalion later defended Quinn's Post, one of the most exposed parts of the Anzac perimeter, with Cannan as post commander. On the Western Front, Cannan was CO of 15th Battalion at the Battle of Pozières and Battle of Mouquet Farm. He later commanded 11th Brigade at the Battle of Messines and the Battle of Broodseinde in 1917, and the Battle of Hamel and during the Hundred Days Offensive in 1918. -

February 2017

MONUMENTALLY SPEAKING National Boer War Memorial Association Newsletter for NSW, SA, WA and ACT Artist’s impression NUMBER 30 – FEBRUARY 2017 NATIONAL BOER WAR MEMORIAL ASSOCIATION National Patron: Chief of the Defence Force, Air Chief Marshal Mark Binskin AC NSW Committee of NBWMA Inc – Chairman: David Deasey NSW Chairman’s Message involvement that has led to the Memorial Welcome to 2017. We stand at the brink project. We also take a look at the full of our most exciting period of time as design and show some of the technical we head toward the dedication of the intricacies behind the sculptures. Finally memorial, 31 May 2017 at 11am. All of our we have some fascinating stories of supporters and interested members of soldiers and equipment from the war the public are invited to attend this great This has been a great endeavour which occasion. The Organising Committee has spanned 15 years at this point. We hopes to have TV screens in place so that have set the target of funds to be raised all attendees can see where ever they are in this financial year at $100.000. As at placed. Seating will be limited compared December 2016 approximately $35.000 to the numbers likely to attend and had been raised, (over $20.000 from NSW) formal invitations for this seating will be leaving $65.000 still short of the target. issued shortly. Please don’t let that stop This issue will be just about our last you from coming, everyone is welcome. chance of getting those funds in. So Inside this issue we look at the please – if you are thinking of donating – circumstances behind Australia’s Boer War please do it now. -

Tom Gilmour HIST480 Dissertation.Pdf

University of Canterbury Propaganda in Prose A Comparative Analysis of Language in British Blue Book Reports on Atrocities and Genocide in Early Twentieth-Century Britain This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of B.A. Honours in History at the University of Canterbury. This dissertation is the result of my own work. Material from the published or unpublished work of other historians used in the dissertation is credited to the author in the footnote references. The dissertation is approximately 9964 words in length. Thomas Gilmour Supervisor: Dr. David Monger Category One HIST480 2016 1 Abstract This paper examines three British Blue Book reports published in early twentieth-century Britain during the war period. The first report examines the invasion of Belgium by the German army and their maltreatment of Belgian people. The second report discusses the Committee of Union and Progress’ acts of cruelty against Armenian Christians. Both of these reports were authored, compiled and then distributed by the British Government in Britain and other Western countries. The third report discusses German colonial rule in South-West Africa and their abuse of ‘native’ Herero. This report was compiled and authored in South- West Africa, but published for a British audience. This dissertation engages in a comparative analysis of these three Blue Book reports. It examines how they are structurally different, but thematically and qualitatively similar. Investigation begins with discussion of the reports’ authors and how they validate claims made in the respective prefaces. Subsequently, there is examination of thematic similarities between each report’s historical narratives. -

Contrasting Portrayals of Women in WW1 British Propaganda

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2015 Vol. 13 of history, propaganda has been aimed at patriarchal Victims or Vital: Contrasting societies and thus, has primarily targeted men. This Portrayals of Women in WWI remained true throughout WWI, where propaganda came into its own as a form of public information and British Propaganda manipulation. However, women were always part of Stacey Reed those societies, and were an increasingly active part History 385 of the conversations about the war. They began to be Fall 2014 targeted by propagandists as well. In war, propaganda served a variety of More than any other war before it, World War I purposes: recruitment of soldiers, encouraging social invaded the every day life of citizens at home. It was the responsibility, advertising government agendas and first large-scale war that employed popular mass media programs, vilifying the enemy and arousing patriotism.5 in the transmission and distribution of information from Various governments throughout WWI found that the the front lines to the Home Front. It was also the first image of someone pointing out of a poster was a very to merit an organized propaganda effort targeted at the effective recruiting tool for soldiers. Posters presented general public by the government.1 The vast majority of British men with both the glory of war and the shame this propaganda was directed at an assumed masculine of shirkers. Women were often placed in the role of audience, but the female population engaged with the encouraging their men to go to war. Many propaganda messages as well. -

Chapter Three

Bridging the Gap between 'War' and 'Peace': The Case of Belgian Refugees in Britain Item Type Book chapter Authors Ewence, Hannah Citation Ewence, H. (2017). Bridging the Gap between 'War' and 'Peace': The Case of Belgian Refugees in Britain. In H. Ewence & T. Grady (Eds.), Minorities and the First World War: From War to Peace. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. Publisher Palgrave Macmillan Download date 29/09/2021 08:39:48 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/620569 Chapter Three Bridging the Gap between ‘War’ and ‘Peace’: The Case of Belgian Refugees in Britain Hannah Ewence August 2014 marked the beginning of a four-year long period of international commemorative activities to honour the centenary of the First World War. The magnified significance awarded to the conflict has brought with it a vigorous national appetite in Britain to locate examples of sacrifice, heroism, and the force of the human spirit. The experience of refugees from Belgium, given shelter in Britain from the earliest days of the conflict, has provided just such a ready-made narrative for a ‘useable past’ which has allowed British politicians to claim moral cache for the historical treatment of immigrants.1 Similarly, within the retelling of that history, the British public have been encouraged to accept the hugely simplistic and yet comforting narrative of their nation as a bulwark of long-entrenched liberal values.2 In reality, whilst the estimated 250,000 so-called ‘Belgian refugees’ who found their way to Britain, largely between August 1914 and the end of 1915 (for exiles from other beleaguered continental nations who had arrived via Belgium also found themselves inaccurately characterised thus), were the recipients of an unprecedented outpouring of localised philanthropy, labour initiatives and an (initially) warm welcome, their treatment fell far from the model of amiable relations often claimed. -

British Imperial Policy and the Indian Air Route, 1918-1932

British Imperial Policy and the Indian Air Route, 1918-1932 CROMPTON, Teresa Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/24737/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version CROMPTON, Teresa (2014). British Imperial Policy and the Indian Air Route, 1918- 1932. Doctoral, Sheffield Hallam Universiy. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk British Imperial Policy and the Indian Air Route, 1918-1932 Teresa Crompton A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2014 Abstract The thesis examines the development of the civil air route between Britain and India from 1918 to 1932. Although an Indian route had been pioneered before the First World War, after it ended, fourteen years would pass before the route was established on a permanent basis. The research provides an explanation for the late start and subsequent slow development of the India route. The overall finding is that progress was held back by a combination of interconnected factors operating in both Britain and the Persian Gulf region. These included economic, political, administrative, diplomatic, technological, and cultural factors. The arguments are developed through a methodology that focuses upon two key theoretical concepts which relate, firstly, to interwar civil aviation as part of a dimension of empire, and secondly, to the history of aviation as a new technology. -

Votes and Proceedings

THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. No. 1. VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTH PARLIAMENT. WEDNESDAY, 9TH JULY, 1913. The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, in the City of Mel- Sbourne, on Wednesday, the ninth day of July, in the fourth year of the Reign of His Majesty King George the Fifth, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and thirteen- 1. On which day, being the first day of the meeting of The Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), Charles Gavan Duffy, C.M.G., Clerk of the House of Representatives, Walter Augustus Gale, Clerk Assistant, and Thomas Woollard, Serjeaut-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk:- PROCLAMATION By His Excellency the Right Honorable THOMAS, Baron DENMAN, Commonwealth of a Member of His Majesty's Most Honorable Privy Council, Knight Australia to wit. Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and DENMAN, Saint George, Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order, Governor-General. Governor-General and. Commander-in-Chief of the Commonwealth of Australia. WHEREAS by the Commonwealth of Australia Constibution Act it is, amongst other things, enacted that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the s§sions..of the Parliament as he thinks fit: Now therefore I, THOMAs, Baron DE:mAN, the Governor-General aforesaid, in exercise of the power conferred by the said Act, do by this my Proclamation appoint Wednesday, the ninth day of July, One thousapd nipe hundred and thirteen, as the day for the said Parliament to assemble and be hplden for the despatch of divers urgent and important affairs: And all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give their attendance accordingly, in the Building known as the Houses of Parliament, situate in Spring-street, in the City of Melbourne, at .the hour of half-past Ten o'clock a.m. -

![[T]He Poet Would Define the Amount of the Unknown Awakening in His Time in the Universal Soul](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3679/t-he-poet-would-define-the-amount-of-the-unknown-awakening-in-his-time-in-the-universal-soul-1573679.webp)

[T]He Poet Would Define the Amount of the Unknown Awakening in His Time in the Universal Soul

[T]he poet would define the amount of the unknown awakening in his time in the universal soul.... Poetry.. .will be in advance. Arthur Rimbaud. (Tijverything in the world exists to end in a book. The qualities required in this work - most certainly genius - frighten me as one of those devoid of them: not to stop there, and granted that the volume requires no signatory, what is it? - the hymn of the connexions between all things, harmony, and joy, entrusted with seeing divinely because the bond, limpid at will, has no expression except in the parallelism of leaves of a book before his glance. Stephane Mallarme [rjt's a faith in what used to be called in old Victorian novels 'the Divine Mystery.' I can't find a better word for it, because it is a mystery to me. All I know is that it pours down love.. .[and] I worship that with my uttermost being. Bruce Beaver 2 Introduction For critics of recent contemporary Australian poetry, the term 'New Poetry' sug• gests primarily the work of those poets published in John Tranter's 1979 anthology, The New Australian Poetry.1 According to Tranter these twenty-four poets, only two of whom are women, formed a 'loose group'2 of writers associated with various poetry readings, little magazines and small presses in Sydney and Melbourne during the late sixties and seventies.3 Although there were many little magazines and small presses associated with the period, and earlier anthologies which had gathered together achievements of the New Poets,4 to a significant extent Tranter's anthology has circumscribed for critics the boundaries of the New Poetry group, and those poets published in the anthology have attracted a measure of critical acclaim. -

Chasing the Monsoon: a Modern Pilgrimage Through India

CHASING THE MONSOON: A MODERN PILGRIMAGE THROUGH INDIA Author: Alexander Frater Number of Pages: 273 pages Published Date: 06 May 2005 Publisher: Pan MacMillan Publication Country: London, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9780330433136 DOWNLOAD: CHASING THE MONSOON: A MODERN PILGRIMAGE THROUGH INDIA Chasing the Monsoon: A Modern Pilgrimage Through India PDF Book In fact, a large portion of the book is taken up by Kerala, justified because of its importance in the scheme of things in this context. The binding of my original copy is broken, with the pages - stained with sweat, tanning oil, seawater, sand and muck - secured between the covers by means of a large rubber band. Almost there! All in all, a highly recommended book. The book is full of chance happenings, and meetings with people who are affable and whimsical at the same time, acting out in a typical way which has come to be characterized by the melange of cultures that India is. Forgot your password? Publication date. Great read. Throughout most of India, the onset of the monsoon rains, the "burst," was eagerly anticipated, the arrival of life- giving rains and cooler weather celebrated for centuries in art, poetry, and song. Though much of the book is littered with climactic Greek and latin phrases about cumulonimbus, wind shear, etc , one does not really need to understand the minutiae to enjoy the book. Henshaw anymore. Keep me logged in. Naipaul's ear for dialog and eye for telling little details, without the cynicism and bitterness. Anderen bekeken ook. I'm cold!! Chasing the Monsoon May 6, , Picador. -

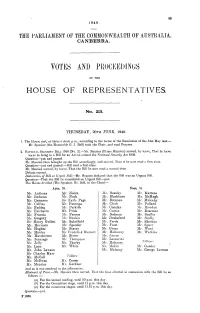

Votes And) Pi{Q0ceei)I Dngs

.1940. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF A1JSTRNLIA, CANBERRA. VOTES AND) PI{Q0CEEI)IDNGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. No. 23. THURSDAY, 20TH JUNE, 1940. 1. The Hlouse miet, ait three o'clock p.m., according to the terms of the Resolution of the 31st May last.- Mi'. Speaker (the Honorable Or. J. Bell) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2. NATIONAL SECURITY' BILL 1940 [No. 2].-Mr. Menzies (Prime Minister) moved, by leave, That he have leave to bring in a Bill for an Act to amend the National Secarity Act 1939. Question-put and passed. Mr. Menzies then brought up the Bill accordingly, and moved, That it be now read a first timie. Question-])ut and passed .- Bill read a first time. Mr. Menzies moved, by leave, That the Bill be now read a second timie. Debate ensued. Declaration of Bill as Urgent Bill.-Mr. Asenzies declared that the B1ill was an Urgent Bill. Question-That the B3ill he considered an Urgent Bill-pt. The House divided (The Speaker, Mr. Bell, in the Chair)- Ayes, 39. Noes, 31. M i . Anthony Mr. Nairn Beasley Mi'. Martens Mr. Badmnan Mr. Nock Mr'. Blackburn *Mr'. McHugh Mi'. Cameron Sir' Ear'le Page M r. Brennan Mr'. Mfulcahy M r. Collins Mr'. Paterson Clar k Mi' Pollard Conelan Mr. Rior'dan Mir. Fadden MI'. Perkii'% Mr. Mr. Fairbairn Mi' . Price Curtin A--Ir. Rlosevear Mri . Francis M.Prowse Mr'. Dedm an M~r. Scullin MALr. Gregory Ri.iankiin Mr. iDrakeford Mr'. Scully Sir Henry Gullett Mr'. Seliolfield Forde Mr. Sheehan Frost Mr.