Reading the Entrails: an Alberta Ecohistory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steward : 75 Years of Alberta Energy Regulation / the Sans Serif Is Itc Legacy Sans, Designed by Gordon Jaremko

75 years of alb e rta e ne rgy re gulation by gordon jaremko energy resources conservation board copyright © 2013 energy resources conservation board Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication ¶ This book was set in itc Berkeley Old Style, designed by Frederic W. Goudy in 1938 and Jaremko, Gordon reproduced in digital form by Tony Stan in 1983. Steward : 75 years of Alberta energy regulation / The sans serif is itc Legacy Sans, designed by Gordon Jaremko. Ronald Arnholm in 1992. The display face is Albertan, which was originally cut in metal at isbn 978-0-9918734-0-1 (pbk.) the 16 point size by Canadian designer Jim Rimmer. isbn 978-0-9918734-2-5 (bound) It was printed and bound in Edmonton, Alberta, isbn 978-0-9918734-1-8 (pdf) by McCallum Printing Group Inc. 1. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board. Book design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. 2. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board — History. 3. Energy development — Government policy — Alberta. 4. Energy development — Law and legislation — Alberta. 5. Energy industries — Law and legislation — Alberta. i. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board. ii. Title. iii. Title: 75 years of Alberta energy regulation. iv. Title: Seventy-five years of Alberta energy regulation. hd9574 c23 a4 j37 2013 354.4’528097123 c2013-980015-8 con t e nt s one Mandate 1 two Conservation 23 three Safety 57 four Environment 77 five Peacemaker 97 six Mentor 125 epilogue Born Again, Bigger 147 appendices Chairs 154 Chronology 157 Statistics 173 INSPIRING BEGINNING Rocky Mountain vistas provided a dramatic setting for Alberta’s first oil well in 1902, at Cameron Creek, 220 kilometres south of Calgary. -

Evolution of Canada's Oil and Gas Industry

Evolution Of Canada’s oil and gas industry A historical companion to Our Petroleum Challenge 7th edition EVOLUTION of Canada’s oil and gas industry Copyright 2004 by the Canadian Centre for Energy Information Writer: Robert D. Bott Editors: David M. Carson, MSc and Jan W. Henderson, APR, MCS Canadian Centre for Energy Information Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2R 0C5 Telephone: (403) 263-7722 Facsimile: (403) 237-6286 Toll free: 1-877-606-4636 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.centreforenergy.com Canadian Cataloguing in Publications Data Main entry under title: EVOLUTION of Canada’s oil and gas industry Includes bibliographical references 1. Petroleum industry and trade – Canada 2. Gas industry – Canada 3. History – petroleum industry – Canada I. Bott, Robert, 1945-II. Canadian Centre for Energy Information ISBN 1-894348-16-8 Readers may use the contents of this book for personal study or review only. Educators and students are permitted to reproduce portions of the book, unaltered, with acknowledgment to the Canadian Centre for Energy Information. Copyright to all photographs and illustrations belongs to the organizations and individuals identified as sources. For other usage information, please contact the Canadian Centre for Energy Information in writing. Centre for Energy The Canadian Centre for Energy Information (Centre for Energy) is a non-profit organization created in 2002 to meet a growing demand for balanced, credible information about the Canadian energy sector. On January 1, 2003, the Petroleum Communication Foundation (PCF) became part of the Centre for Energy. Our educational materials will build on the excellent resources published by the PCF and, over time, cover all parts of the Canadian energy sector from oil, natural gas, coal, thermal and hydroelectric power to nuclear, solar, wind and other sources of energy. -

Calgary Royals Graduates: Where Are They Now?

CALGARY ROYALS GRADUATES: WHERE ARE THEY NOW? Adams, Matthew - KIJHL Osoyoos Coyotes, University University, Red Deer College, Eckville Eagles NCHL- Springfield Indians, Louisville Icehawks, Drafted by the of Victoria AB, Calgary Royals Coach New York Islanders 1989 drafted round 11 #212 Allan, Shane - WHL Kootenay Ice, BCHL Penticton Vees Colleens, Mike - Royals, AJHL Ethan Jamernik - Fort McMurray Oil Barons AJHL Allen, Matt - 2002-2004. Royals Junior A, AJHL, Collett, Jeff - 2007-2010 Calgary Royals, NCAA Ethien, Karlen - Junior A Royals MRC, SAIT Colorado College, AMBHL CRAA Bantam AAA Evans, Jordan - SJHL Yorkton Terriers, SJHL Allen, Peter - Calgary Canucks AJHL, Yale University, Assistant Coach Kindersley Klippers Pittsburgh Penguins, Team Canada, Vancouver Con, Rob - Calgary Royal, AJHL Calgary Canucks, Farrer, Ben - Calgaryy Canucks, Providence College, Canucks, Germany NCAA University of Alaska Anchorage, IHL Trenton Devils, Wheeling Nailers Ference, Brad. Allen, Sean - Golden Rockets KIJHL, Princeton Posse Indianapolis Ice, NHLChicago Blackhawks, AHL Spokane Chiefs, Florida Panthers, Phoenix Coyotes, KIJHL, Nelson Leafs KIJHL Albany River Rats, AHL Rochester Americans, NHL New Jersey Devils, Tri-City Americans, Louisville Allen, Taylor - AJHL Lloydminster Bobcats Buffalo Sabres Panthers, Morzine-Avoriaz, San Antonio Rampage, Anderson, Brett - Kimberley Dynamiters KIJHL Conacher, Dan - Calgary Royals, AJHL Okotoks Albany River Rats, Omaha Ak-Sar-Ben Knights, Anderson, Isaiah - Grand Forks Border Bruins KIJHL Oilers, SJHL La Ronge Ice Wolves, CIS Dalhousie Calgary, Flames, Grand Rapids Griffins, Drafted by the Anklewich, Bennett - Nelson Leafs KIJHL University Vancouver Canucks in the 1997 draft round 1 #10 Anklewich, Cameron - NOJHL Espanola Express, Conacher, Pat - AJHL Calgary Canucks, BCHL Ferguson, Logan - AJHL Canmore Eagles, Holy Cross NCAA III Kings College Penticton Panthers, SJHL Yorkton Terriers, NCAA Div I Anklewich, Chris - Calgary Royals Jr. -

Living in Edmonton

LIVING I N EDMONTON A HANDY GUIDE TO WORK AT BioWare EDMONTON MAIN MENU EDMONTON FACTS ACCOMODATIONS TRANSPORTATION CULTURE & FUN BIOWARE PHOTOBOOTH INTRO We would like to thank you for your interest in BioWare, a division of EA. We know working in another country can be a challenge, but it can also be a unique opportunity to get to know a new place, culture, and people and have a great amount of new experiences. This guide has useful information about various topics that should answer many of your questions, but feel free to contact your recruiter to address any questions or concerns you may have. EDMONTON FACTS COST OF LIVING We imagine that you are wondering if your income will be enough to get by in Edmonton. Below you can find some examples of regular consumption products along with their average prices in the city. Lunch: $12-$15 Cup of cappuccino: $4.00 1 pint of beer (bar): $5.00 Drink (bar): $6.00 Milk (1 L): $2.15 Beefsteak (1lbs): $12.00 Bread loaf: $2.50 Pasta (packet): $3.00 Bag of chips: $2.00 Roasted chicken: $10.00 Can of Coke: 1.50 Chocolate bar: $1.50 Gyms $30-$60 Movie ticket: $13.00 Amusement Park: $20-$40 FINDING ACCOMODATIONS It is highly recommended to start your house hunting and checking out all other amenities over the internet. Below you can find some websites that could prove useful in your search. Useful Links Housing Family Resources City information Padmapper Public Schools General information Rent Edmonton Catholic Schools Edmonton Tourism Edmonton Kijiji Childcare Discover Edmonton Realtor.ca Child Friendly Immigration Alberta Craigslist Health Care Services Edmonton Public Library Environment Telephone Find a Doctor Edmonton Recycling Hospitals Travel Alberta Video Rogers Telus Pets Bell Fido General Info Edmonton Humane Internet/Cable Society Vets & Pet Hospitals Bell Pet Licences Telus Shaw Energy Epcor Enmax EDMONTON BY DISTRICTS 1 – North West 2 – North East 2 · A suburban area of Edmonton. -

TALES of Lismijjhrjimoil .^^Éèmkfl Tm*

TALES OF liSMIJJhrJIMoiL .^^ÉÈMkfl tm*. liât _i FIRST OIL WELL IN WESTERN CANADA NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE OF CANADA The information in this pamphlet is from the book Oil City: Black Cold in Waterton Park by Johan F. Dormaar and Robert A. Watt available at the Waterton Natural History Association's Heritage Centre. D.S ERV "One time, on their way to Chief Mountain, my 1889t0l893 grandparents stopped near this site to have lunch. My In 1889, Allan Patrick staked and filed a mineral claim near grandmother went to get water. She located a spring Oil Creek (now known as Cameron Creek). In the following but she didn't draw any water out because it had a years, more than 150 mineral claims were filed throughout peculiar color to it. It looked blackish to her. She got a the region. There were a few attempts to sink oil wells but dipper full and examined it carefully; the contents by 1893, all had failed. were filthy, oily and thicker than water. It seemed that the black liquid running into the spring was coming Waterton's natural oil seeps were well known by Aboriginal from another source. She located the source of the peoples who used it as lubricant or medicine. Exactly how, black liquid and took a sample home to show her when and who among the settlers first learned of the oil is husband." Hansen Bearspaw, Stoney Elder the source of much debate, myth and story. Waterton seems like an unlikely place for an oil boom - but it happened! Enjoy some tales of that time as you use the map in the middle of this booklet to visit some historic locations. -

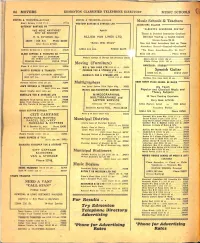

Try Edmonton Telephone Directory

84 MOVERS EDMONTON CLASSIFIED TELEPHONE DIRECTORY MUSIC SCHOOLS MOVERS & TRANSFERS—Continued MOVERS & TRANSFERS—CoDtloucd Music Schools & Teachers Eran's Delivery H325 79 st TTm WESTERN CARTAGE ft STORAGE LTD ACCOROIAHA COLLEGE — eATlWAY BARTASE GO "ALBERTA'S ACCORDION CENTRE" "WE MOVE ANYTHING" Agents CITY OR COUNTRY Theory St Practical InstrucUoo Combiaed W. M. DAVroSON. Mgr. ALLIED VAN LINES LTD. Individual Teaching — Graded Courses 10439 • 105 Ave. Phone 21B05 Starter Course $8 00 "Nation Wide Movers" After Hours 27428 New and Used Accordions Sold on Terms I \ Accordions Rented—Repaired—Overhauled 12010 111 Ave. PHONE 86175 Gateway Cartage Co 3 - 10510 90 st . .2742S "We Know Accordions—Try Us First" OLOBE EXPRESS A TRANSFER CO 8511 118 Ave. Phone 75408 ANY TIME — ANYWHERE Western Cartage & Storage Ltd CPQ Sbeds 21631 ED. CURTIS and S. CHUBCU Adams Alec H 1052S 126 st 84287 11344-93 Street PHONE 77765 Moving (Furniture) Alberta College 10041 101 st 42545 Glover H A 8629 103A ava ... BARCELONA STUDIOS' 24506 BIG 4 VAN LINES LTD1Q625 92 st .. .21414 HARRY'S EXPRESS A TRANSFER CONQDGN VAN & STORAGE LTD Spanish Guitar 9417 ni ave..21335 10588 101 St PHONE 21847 "EFFICIENT (24.H0UR) SERVICE" MCNEILL'S VAN & STORAGE LTD 9611 107 Ave. PHONE 20647 10112 114 Et. .84848 Barlbtau Miss Irene 9809 82 are 34519 BOON HARRY PIAHO SCHOOL OF MUSIC Horwood Transfer 9945 69 ave 31844 Multigraphers JIM'S EXPRESS ft TRANSFER Ace Letter Service 333A Teelcr btdg. .. 26621 We Teach 9639 I03A ave..26669 WATTS MULTIORAPHIHO COMPANY Popular and Classical Music and Kenn's Tfamfer G628 102A ave 27536 Theory Subjects HrNEILL'S van ft STOAAQE LTD MIMEOGRAPHING, 10 Years Teaching Experience 10112 114 st 84848 MULTIGRAPMING and Merrtianti Truck Service 8702 78 ave ....33588 LETTER SERVICE Harry Boon, A.T.C.M. -

Great Canadian Oil Patch, 2Nd Edition

1 THE GREAT CANADIAN OIL PATCH, SECOND EDITION. By Earle Gray Drilling rigs in the Petrolia oil field, southwestern Ontario, in the 1870’s. The rigs were sheltered to protect drillers from winter snow and summer rain. Photo courtesy Lambton County Museums. “Text from ‘The Great Canadian Oil Patch. Second edition: The Petroleum era from birth to peak.’ Edmonton: JuneWarren Publishing, 2005. 584 pages plus slip cover. Free text made available courtesy JWN Energy. The book is out of print but used copies are available from used book dealers.” Contents Part One: In the Beginning xx 1 Abraham Gesner Lights Up the World xx 2 Birth of the Oil Industry xx 3 The Quest in the West: Two Centuries of Oil Teasers and Gassers xx 4 Turner Valley and the $30 Billion Blowout xx 5 A Waste of Energy xx 6 Norman Wells and the Canol Project xx 7 An Accident at Leduc xx 8 Pembina: The Hidden Elephant xx 2 Part Two: Wildcatters and Pipeliners xx 9 The Anatomy of an Oil Philanthropy xx 10 Max Bell: Oil, Newspapers, and Race Horses xx 11 Frank McMahon: The Last of the Wildcatters xx 12 The Fina Saga xx 13 Ribbons of Oil xx 14 Westcoast xx 15 The Great Pipeline Debate xx 16 The Oil Sands xx 17 Frontier Energy: Cam Sproule and the Arctic Vision xx 18 Frontier Energy: From the End of the Mackenzie River xx 19 Don Axford and his Dumb Offshore Oil Idea xx Part Three: Government Help and Hindrance xx 20 The National Oil Policy xx 21 Engineering Energy and the Oil Crisis xx 22 Birth and Death of the National Energy Program xx 23 Casualties of the NEP xx Part Four: Survivors xx 24 The Largest Independent Oil Producer xx 25 Births, obituaries, and two survivors: the fate of the first oil ventures xx Epilogue: The End of the Oil and Gas Age? xx Bibliography xx Preface and acknowledgements have been omitted from this digital version of the book. -

Chamber Report Message from the President & Ceo

2019 CHAMBER REPORT MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT & CEO an active participant in the city’s members for your ideas and Municipal Development plan input. process, ensuring the needs of our business community are Our community engagement being heard. We are proud to and events continue to expand. be part of the Villeneuve Airport We have an amazing team of Task force and look forward to dedicated staff and volunteers the development of business who work tirelessly to bring our and opportunities over the next members and residents events few years. that we can all be proud of. The Chamber is proud of the As we look towards 2020, work that we do during election we look forward to the years bringing the candidates opportunities that lie ahead. to our business members as We are extremely fortunate to well as facilitating and hosting have a very dedicated Board of the public election forums. This Directors who are committed year was no exception with to ensuring the Chamber the Provincial, Federal and a represents our business byelection in Sturgeon County community. The Board, along taking place. with our very active Government Through the enormous Affairs Committee will continue challenges this past year, we We continued with our to monitor changes that have been inspired by the information workshops could impact our businesses many businesses who have and roundtable discussions and will provide information continued to adapt and show throughout the year as we on emerging issues. Our resilience and perseverance. recognize the importance in Chamber network will continue We were thrilled to welcome facilitating opportunities for to advocate on behalf of our 170 new members this year, increased knowledge and business community, locally, most of which were new providing a platform for our provincially and federally. -

Exhibition Lands Historical Report

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw ertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopa Edmonton Exhibition Lands sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf Area Redevelopment Plan Phase II ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj 3/17/2018 klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzKen Tingley xcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcv bnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwe rtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjk lzxcvbnmrtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwe 1 Table of Contents Preface: First Nations Lands and at the Exhibition 2 The Edmonton Exhibition Lands: Chapter 1 4 Theme Chapter 1: The Exhibition: Deep Roots in Agriculture 61 Theme Chapter 2: Borden Park: Playground, Midway and Zoo 75 Theme Chapter 3: Horse Racing at the Exhibition 85 Theme Chapter 4: Midways at the Exhibition: Rides, Vice, and Scandals 100 Theme Chapter 5: Attractions at the Exhibition 1914-1961 105 Theme Chapter 6: Everyone Loves A Parade 108 Theme Chapter 7: Rodeo Days at the Exhibition 115 Theme Chapter 8: Athletics and Sports at the Exhibition: Horseshoes to Hockey 121 Conclusion 130 Appendix: Historical Land Titles; City of Edmonton Ownership of Exhibition Lands 130 Appendix: Edmonton Gardens summary 131 Aerial Views and Maps 133 2 Preface: First Nations Lands and at the Exhibition Hundreds of archaeological sites indicate aboriginal use of the land in what is now Edmonton and district for at least 5000 years. These first people hunted, fished and gathered raw resources to be processed into tools and other useful materials. By the time the first fur trade forts were established in the district in 1795, the Cree had named this area Otinow (a place where everyone came). However, First Nations may have used this area well before this European contact. About 12,000 years ago the study area was under a large lake, with a vast area surrounding it. -

Atlas Home Systems

Trades & Supporters Atlas Home Systems AV Works A&M Concrete B Wright Drywall AAA-1 Signs Baba Landscaping Access Plumbing Babylon Painting Aclark Roofing Baywest Projects ACQ Built Bell Media Ancient Stoneworks Benks Painting Ann Love Interiors Best Plumbing Aquatech Mechanical Big Dogs Production Aspen Commercial and Residential Inspections Big Johns Foundations Gratz Weeping Tile Buttar Woodworks Haden Pumping Canada Post Harvard Radio Canadian Western Bank Home Based Signs Capital Concrete Home Theatre Installs Casa Brio Design IB Engineering CBC Icon Flooring City Glass Igloo Building Supplies City Scapes J and P Construction ClearSkies Heating & Air Conditioning Jay-T Custom Coatings Coast Wholesale Appliances Jetco Mechanical Concrete Inc. JFS Electrical Corus Radio Joes Construction Cuda Contracting JTD Contracting Dannburg Flooring Lads Foundations Designs by Dreger Lafarge Divine Flooring Specialist Leading Edge Interior Railing Durabuilt Lenbeth Weeping Tile Durapro Parging LW Contracting Edmonton Journal McCallum Elms Weeping Tile Metro News Euro Design Mustang Helical Piling Expert Electrical Nava Cabinet Solutions F Andersen Drywall Nerval Corp Fancy Doors and Mouldings Newcap Radio Fireplace by Weiss Johnson Noble Interiors Folkgraphis Frames Norelco/Richelieu Garage Zone Inc. Norstair Gatt Heating Northlands Gem Cabinets Northstar Heating and Ventilation Gemco Oil City Signs Global Television Overhead Door Company Park Lighting Sherwood Steel Pattison Outdoor Spindle Factory Pattison Radio Group St. Albert Gazette Plutonic -

What Can Art Do About Pipeline Politics?

AGAINST the DAY Brian Holmes What Can Art Do about Pipeline Politics? Chicago is known for its blues bars, its futures markets, its gun crimes, and the sprawling rail yards that make it the freight hub of North America. What’s missing from that list is a vast nexus of underground pipes that exerts a subterranean influence on the entire metropolitan region. Without the knowledge of most inhabitants, the “Windy City” has become the Mid- western capital of the oil industry. Let us have a look from the four directions. Up north, Enbridge’s main lines from Edmonton take aim at Chicago from the 450-acre Superior Ter- minal in Duluth, Minnesota. One of these pipes, infamous Line 61, is gradu- ally being tripled in capacity to reach a staggering 1.2 million barrels of diluted bitumen a day, more than enough to replace the defeated Keystone XL project. A northward-flowing line, also operated by Enbridge, pumps diluent from the massive BP refinery on the southeast edge of Chicago to buyers in the faraway Tar Sands region. From the south, three major pipe- lines connect Texas oil wells to Chicago area refineries by way of the giant storage hubs of Patoka, Illinois, and Cushing, Oklahoma. Two more Enbridge lines flow in the opposite direction, bringing the deluge of Tar Sands oil within reach of thirsty Gulf Coast markets. Out west, the pipeline story con- tinues along the rails, in the form of hundred-car-long tanker trains filled to bursting with explosive Bakken crude. Some forty of these rolling pipe- lines—also known as “bomb trains”—cross the densely populated Chicago metro area every week, so far without any catastrophic incident (the closest explosion yet was in Galena, some 150 miles away). -

Patchett, M. M., & Lozowy, A. (2012). Reframing the Canadian Oil Sands

Patchett, M. M., & Lozowy, A. (2012). Reframing the Canadian Oil Sands. Imaginations: Journal of Cross-Cultural Image Studies , (3-2). http://www.csj.ualberta.ca/imaginations/wp- content/uploads/2012/09/011_Patchett_Lozowy_V2.pdf Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ REfREFRAMINGRAMING THE CANADIAN OIL SANDSThE CANAdIAN OIl S ANdS Curatorial Essay by MERLE Patchett • Photographs AND Essay by ANDRIkO LOzOwy “Reframing the Canadian Oil Sands” is a collaborative Cet article est une collaboration entre le photographe exchange between photographer Andriko Lozowy and Andriko Lozowy et la géographe culturelle Merle cultural geographer Merle Patchett that engages pho- Patchett. La photographie et la théorie photographique tography and photographic theory to evoke a more crit- y sont mises à profit afin de susciter un engagement ical and politically meaningful visual engagement with visuel significatif des points de vue politique et critique the world’s largest capital oil project. Since the appear- avec le plus important projet pétrolier à ce jour. Depuis ance of Edward Burtynsky’s aerial and abstracted pho- les photographies aériennes de la région des sables tographic-mappings of the region, capturing the scale of bitumineux par Edward Burtynsky, cette manière de the Oil Sands from ‘on high’ has become the dominant photographier à distance les zones d’exploitation a visual imaginary.