Conflicts Between Intellectual Property Protections When a Character Enters the Public Domain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

2013 Movie Catalog © Warner Bros

1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney © TriStar Pictures © Warner Bros. © NBC Universal © Columbia Pictures Industries, ©Inc. Summit Entertainment 2013 Movie Catalog Movie 2013 Inc. Pictures, Motion Swank 1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com MOVIES Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © New Line Cinema © 2013 Disney © Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney/Pixar © Summit Entertainment Promote Your movie event! Ask about FREE promotional materials to help make your next movie event a success! 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie Catalog TABLE OF CONTENTS New Releases ......................................................... 1-34 Swank has rights to the largest collection of movies from the top Coming Soon .............................................................35 Hollywood & independent studios. Whether it’s blockbuster movies, All Time Favorites .............................................36-39 action and suspense, comedies or classic films,Swank has them all! Event Calendar .........................................................40 Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm Classics ...................................................................41-42 Disney 2012 © Date Night ........................................................... 43-44 TABLE TENT Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm TM & © Marvel & Subs 1-800-876-5577 | www.swank.com Environmental Films .............................................. 45 FLYER Faith-Based -

In the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama Southern Division

Case 6:09-cv-02258-JEO Document 15 Filed 11/02/10 Page 1 of 13 FILED 2010 Nov-02 AM 11:54 U.S. DISTRICT COURT N.D. OF ALABAMA IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA SOUTHERN DIVISION ERIC S. ESCH, a/k/a BUTTERBEAN ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) 6:09-cv-02258-JEO ) UNIVERSAL PICTURES COMPANY, INC; ) NBC UNIVERSAL, INC.; and ) ILLUMINATION ENTERTAINMENT ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION Before the court is the motion of defendants Universal Pictures Company, Inc. (“Universal”), NBC Universal, Inc. (“NBC”), and Illumination Entertainment (“Illumination”), to dismiss this action pursuant to Rule 12(b)(6) of the FEDERAL RULES OF CIVIL PROCEDURE, on the ground that the complaint fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted. (Doc. 7).1 Additionally, before the court is the motion of the defendants to strike the affidavit of Corey L. Fischer offered in support of the plaintiff’s response to the motion to dismiss. (Doc. 11). The parties have been afforded an opportunity to brief the relevant issues. Upon consideration, and as fully discussed below, the court finds that the defendants’ motion to dismiss and motion to strike are due to be granted. BACKGROUND Procedural History The plaintiff, Eric S. Esch (“Esch”), filed a complaint in this court, premised on diversity 1References herein to “Doc. ___” are to the document numbers assigned by the Clerk of the Court and located at the top of each document. Case 6:09-cv-02258-JEO Document 15 Filed 11/02/10 Page 2 of 13 jurisdiction, against defendants Universal, NBC, and Illumination, alleging that the defendants appropriated his likeness without his consent for use in a film trailer for a movie entitled Despicable Me. -

Before Bogart: SAM SPADE

Before Bogart: SAM SPADE The Maltese Falcon introduced a new detective – Sam Spade – whose physical aspects (shades of his conversation with Stein) now approximated Hammett’s. The novel also originated a fresh narrative direction. The Op related his own stories and investigations, lodging his idiosyncrasies, omissions and intuitions at the core of Red Harvest and The Dain Curse. For The Maltese Falcon Hammett shifted to a neutral, but chilling third-person narration that consistently monitors Spade from the outside – often insouciantly as a ‘blond satan’ or a smiling ‘wolfish’ cur – but never ventures anywhere Spade does not go or witnesses anything Spade doesn’t see. This cold-eyed yet restricted angle prolongs the suspense; when Spade learns of Archer’s murder we hear only his end of the phone call – ‘Hello . Yes, speaking . Dead? . Yes . Fifteen minutes. Thanks.’ The name of the deceased stays concealed with the detective until he enters the crime scene and views his partner’s corpse. Never disclosing what Spade is feeling and thinking, Hammett positions indeterminacy as an implicit moral stance. By screening the reader from his gumshoe’s inner life, he pulls us into Spade’s ambiguous world. As Spade consoles Brigid O’Shaughnessy, ‘It’s not always easy to know what to do.’ The worldly cynicism (Brigid and Spade ‘maybe’ love each other, Spade says), the coruscating images of compulsive materialism (Spade no less than the iconic Falcon), the strings of point-blank maxims (Spade’s elegant ‘I don’t mind a reasonable amount of trouble’): Sam Spade was Dashiell Hammett’s most appealing and enduring creation, even before Bogart indelibly limned him for the 1941 film. -

Becoming Legendary: Slate Financing and Hollywood Studio Partnership in Contemporary Filmmaking

Kimberly Owczarski Becoming Legendary: Slate Financing and Hollywood Studio Partnership in Contemporary Filmmaking In June 2005, Warner Bros. Pictures announced Are Marshall (2006), and Trick ‘r’ Treat (2006)2— a multi-film co-financing and co-production not a single one grossed more than $75 million agreement with Legendary Pictures, a new total worldwide at the box office. In 2007, though, company backed by $500 million in private 300 was a surprise hit at the box office and secured equity funding from corporate investors including Legendary’s footing in Hollywood (see Table 1 divisions of Bank of America and AIG.1 Slate for a breakdown of Legendary’s performance at financing, which involves an investment in a the box office). Since then, Legendary has been a specified number of studio films ranging from a partner on several high-profile Warner Bros. films mere handful to dozens of pictures, was hardly a including The Dark Knight, Inception, Watchmen, new phenomenon in Hollywood as several studios Clash of the Titans, and The Hangoverand its sequel. had these types of deals in place by 2005. But In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, the sheer size of the Legendary deal—twenty five Legendary founder Thomas Tull likened his films—was certainly ambitious for a nascent firm. company’s involvement in film production to The first film released as part of this deal wasBatman an entrepreneurial endeavor, stating: “We treat Begins (2005), a rebooting of Warner Bros.’ film each film like a start-up.”3 Tull’s equation of franchise. Although Batman Begins had a strong filmmaking with Wall Street investment is performance at the box office ($205 million in particularly apt, as each film poses the potential domestic theaters and $167 million in international for a great windfall or loss just as investing in a theaters), it was not until two years later that the new business enterprise does for stockholders. -

Ebook Download Dolph Lundgren: Train Like an Action

DOLPH LUNDGREN: TRAIN LIKE AN ACTION HERO : BE FIT FOREVER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dolph Lundgren | 192 pages | 02 Jan 2018 | Skyhorse Publishing | 9781510728981 | English | New York, NY, United States Dolph Lundgren: Train Like an Action Hero : Be Fit Forever PDF Book Aug 02, Randy Daugherty rated it really liked it. Then take a lesson from internationally renowned action hero Dolph Lundgren. More Details Like we said before the man is a talented athlete with a wealth of knowledge that any fitness fanatic would find helpful. Related Articles. The philosophy is centered around lifestyle choices instead of diets or shallow motives. Joshua Huesser rated it it was amazing Dec 26, Briefing: The reasons you need to get fit 2. Follow Us. Get A Copy. Thank you for signing up, fellow book lover! Are you ready to take your exercise and fitness routine to the next level? Dolph Lundgren: Train Like an Action Hero —his autobiographical training guide—features weekly training programs, daily menu planners, guides to equipment and gear, fantastic photos from behind the scenes of Hollywood action movies, and much more! Maybe someday, he'll find the time. The man is an action movie icon whose role as the Soviet boxer Ivan Drago brought him great acclaim. Your First Name. Add to cart. No trivia or quizzes yet. Weaponry: How to best combine strength exercises, cardiovascular, and flexibility training 4. Overview Are you ready to take your exercise and fitness routine to the next level? Dolph has created a personal philosophy of fitness based on martial arts, yoga, strength training, biochemical research, professional sports, and over forty starring roles in classic action films. -

COVID-19 Rush Journal Club

COVID-19 Rush Journal Club NOVEL CORONAVIRUS SARS-COV-2. Transmission electron micrograph of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles, iso- lated from a patient. Image captured and color-enhanced at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID Available at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/niaid/49597768397/in/al- bum-72157712914621487/. Accessed April 19, 2020. This document is a collection of efforts from students of Rush University. It provides brief reviews of research articles regarding COVID-19. We hope that this will be helpful to clini- cians, students, community leaders, and the general public. This document, however, does not act as a replacement of the original source documents. Please use the DOI on each page to read more. Student Editors Blake Beehler, MD John Levinson, MS2 Alice Burgess, MS2 Luke McCormack, MS2 Alyssa Coleman, MS3 Diana Parker, MS2 Shyam Desai, MD Elena Perkins, MS3 Joseph Dodson, MS1 Hannah Raff, MS3 Joshua Doppelt, MD Ayesan Rewane, MSCR Emily Hejna, MS2 Audrey Sung, MS3 Danesha Lewis, PhD student Literature Selection Christi Brown, MS2 Lindsay Friedman, MS3 Danesha Lewis, PhD Student Travis Tran, MS2 Student Editors in Chief Joseph deBettencourt, MS3 Alyssa Coleman, MS3 Lindsay Friedman, MS3 Leah Greenfield, MS2 Beth Hall, MD Morgan Sturgis, MS2 Travis Tran, MS2 Ashley Wehrheim, MS2 Kaitlyn Wehrheim, MS2 Bijan Zarrabi, MS2 Faculty Editors and Mentors Frank Cockerill, MD - Adjunct Professor of Medicine Mete Altintas, PhD - Director, Translational and Preclinical Studies Rachel Miller, -

The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2015 "We want to get down to the nitty-gritty": The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form Kendall G. Pack Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Pack, Kendall G., ""We want to get down to the nitty-gritty": The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form" (2015). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 4247. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/4247 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “WE WANT TO GET DOWN TO THE NITTY-GRITTY”: THE MODERN HARDBOILED DETECTIVE IN THE NOVELLA FORM by Kendall G. Pack A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in English (Literature and Writing) Approved: ____________________________ ____________________________ Charles Waugh Brian McCuskey Major Professor Committee Member ____________________________ ____________________________ Benjamin Gunsberg Mark McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2015 ii Copyright © Kendall Pack 2015 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT “We want to get down to the nitty-gritty”: The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form by Kendall G. Pack, Master of Science Utah State University, 2015 Major Professor: Dr. Charles Waugh Department: English This thesis approaches the issue of the detective in the 21st century through the parodic novella form. -

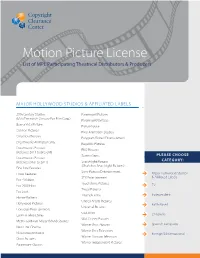

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers MAJOR HOLLYWOOD STUDIOS & AFFILIATED LABELS 20th Century Studios Paramount Pictures (f/k/a Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp.) Paramount Vantage Buena Vista Pictures Picturehouse Cannon Pictures Pixar Animation Studios Columbia Pictures Polygram Filmed Entertainment Dreamworks Animation SKG Republic Pictures Dreamworks Pictures RKO Pictures (Releases 2011 to present) Screen Gems PLEASE CHOOSE Dreamworks Pictures CATEGORY: (Releases prior to 2011) Searchlight Pictures (f/ka/a Fox Searchlight Pictures) Fine Line Features Sony Pictures Entertainment Focus Features Major Hollywood Studios STX Entertainment & Affiliated Labels Fox - Walden Touchstone Pictures Fox 2000 Films TV Tristar Pictures Fox Look Triumph Films Independent Hanna-Barbera United Artists Pictures Hollywood Pictures Faith-Based Universal Pictures Lionsgate Entertainment USA Films Lorimar Telepictures Children’s Walt Disney Pictures Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios Warner Bros. Pictures Spanish Language New Line Cinema Warner Bros. Television Nickelodeon Movies Foreign & International Warner Horizon Television Orion Pictures Warner Independent Pictures Paramount Classics TV 41 Entertaiment LLC Ditial Lifestyle Studios A&E Networks Productions DIY Netowrk Productions Abso Lutely Productions East West Documentaries Ltd Agatha Christie Productions Elle Driver Al Dakheel Inc Emporium Productions Alcon Television Endor Productions All-In-Production Gmbh Fabrik Entertainment Ambi Exclusive Acquisitions -

On Modernity, Identity and White-Collar Boxing. Phd

From Rookie to Rocky? On Modernity, Identity and White-Collar Boxing Edward John Wright, BA (Hons), MSc, MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. September, 2017 Abstract This thesis is the first sociological examination of white-collar boxing in the UK; a form of the sport particular to late modernity. Given this, the first research question asked is: what is white-collar boxing in this context? Further research questions pertain to social divisions and identity. White- collar boxing originally takes its name from the high social class of its practitioners in the USA, something which is not found in this study. White- collar boxing in and through this research is identified as a practice with a highly misleading title, given that those involved are not primarily from white-collar backgrounds. Rather than signifying the social class of practitioner, white-collar boxing is understood to pertain to a form of the sport in which complete beginners participate in an eight-week boxing course, in order to compete in a publicly-held, full-contact boxing match in a glamorous location in front of a large crowd. It is, thus, a condensed reproduction of the long-term career of the professional boxer, commodified for consumption by others. These courses are understood by those involved to be free in monetary terms, and undertaken to raise money for charity. As is evidenced in this research, neither is straightforwardly the case, and white-collar boxing can, instead, be understood as a philanthrocapitalist arrangement. The study involves ethnographic observation and interviews at a boxing club in the Midlands, as well as public weigh-ins and fight nights, to explore the complex interrelationships amongst class, gender and ethnicity to reveal the negotiation of identity in late modernity. -

Ways Accompanies Our Review of Official Court Granted Certiorari

2764 125 SUPREME COURT REPORTER 545 U.S. 912 first and second displays to the third. Giv- Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, 380 en the presumption of regularity that al- F.3d 1154, affirmed, and the Supreme ways accompanies our review of official Court granted certiorari. action, see n. 9, supra, the Court has iden- Holding: The Supreme Court, Justice tified no evidence of a purpose to advance Souter, held that one who distributes a religion in a way that is inconsistent with device with the object of promoting its use our cases. The Court may well be correct to infringe copyright, as shown by clear in identifying the third displays as the fruit expression or other affirmative steps taken of a desire to display the Ten Command- to foster infringement, is liable for the ments, ante, at 2740, but neither our cases resulting acts of infringement by third par- nor our history support its assertion that ties. such a desire renders the fruit poisonous. Vacated and remanded. * * * Justice Ginsburg filed concurring opinion For the foregoing reasons, I would re- in which Chief Justice Rehnquist and Jus- verse the judgment of the Court of Ap- tice Kennedy joined. peals. Justice Breyer filed concurring opinion in which Justice Stevens and Justice O’Con- , nor joined. 1. Copyrights and Intellectual Property O77 One infringes a copyright contribu- 545 U.S. 913, 162 L.Ed.2d 781 torily by intentionally inducing or encour- METRO–GOLDWYN–MAYER aging direct infringement and infringes STUDIOS INC., et al., vicariously by profiting from direct in- Petitioners, fringement while declining to exercise a v. -

Friday, May 29, 2020 6:30 P.M

FRIDAY, MAY 29, 2020 6:30 P.M. | STEPHENS CO. EXPO CENTER | DUNCAN, OKLAHOMA 6:30 P.M. ON FRIDAY, MAY 29, 2020 STEPHENS CO. EXPO CENTER DUNCAN, OKLAHOMA Welcome to the 2020 Bred to Buck Sale, With all the changes going on in the world, one thing that remains the same is our focus of producing elite bucking bulls. For over 35 years, we have strived to produce the very best in the business. We know the competition gets better every year so we work to remain a leader in the industry. One thing we have proven is all the great bulls are backed by proven cow families. Our program takes great pride in our cows and we KNOW they are the key to our operation. We sell 200 plus females each year between the Fall Female Sale and this Bred to Buck Female Sale, so we have our cow herd fine-tuned to only the most proven cow families. It is extremely hard to select females for this sale knowing that many of our very best cows will be leaving the program. However, we do take pride in the success our customers have with the Page genetics. There are so many great success stories from our customers, and we can’t begin to tell them all. Johna Page Bland, Office 2020 is a year we will never forget, our country has experienced changes and regulations that we have never seen throughout history. We will get through this, but we will have to 580.504.4723 // Fax: 580.223.4145 make some adjustments along the way.