A WALK in the PARK an Esplanade Is a Long, Open, Level Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscape Assessment for the Buckskin Mountain Area, Wildlife Habitat Improvement

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) Depository) 11-19-2004 Landscape Assessment for the Buckskin Mountain Area, Wildlife Habitat Improvement Bureau of Land Management Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Bureau of Land Management, "Landscape Assessment for the Buckskin Mountain Area, Wildlife Habitat Improvement" (2004). All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository). Paper 77. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs/77 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bureau of Land Management Phone 435.644.4300 Grand Staircase-Escalante NM 190 E. Center Street Fax 435.644.4350 Kanab, UT 84741 Landscape Assessment for the Buckskin Mountain Area Wildlife Habitat Improvement Version: 19 November 2004 Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction..................................................................................................................... 3 A. Background and Need for Management Activity ................................................................... 3 B. Purpose ..................................................................................................................................... -

Chapter 2 Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

CHAPTER 2 PALEOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY OF THE GRAND CANYON PAIGE KERCHER INTRODUCTION The Paleozoic Era of the Phanerozoic Eon is defined as the time between 542 and 251 million years before the present (ICS 2010). The Paleozoic Era began with the evolution of most major animal phyla present today, sparked by the novel adaptation of skeletal hard parts. Organisms continued to diversify throughout the Paleozoic into increasingly adaptive and complex life forms, including the first vertebrates, terrestrial plants and animals, forests and seed plants, reptiles, and flying insects. Vast coal swamps covered much of mid- to low-latitude continental environments in the late Paleozoic as the supercontinent Pangaea began to amalgamate. The hardiest taxa survived the multiple global glaciations and mass extinctions that have come to define major time boundaries of this era. Paleozoic North America existed primarily at mid to low latitudes and experienced multiple major orogenies and continental collisions. For much of the Paleozoic, North America’s southwestern margin ran through Nevada and Arizona – California did not yet exist (Appendix B). The flat-lying Paleozoic rocks of the Grand Canyon, though incomplete, form a record of a continental margin repeatedly inundated and vacated by shallow seas (Appendix A). IMPORTANT STRATIGRAPHIC PRINCIPLES AND CONCEPTS • Principle of Original Horizontality – In most cases, depositional processes produce flat-lying sedimentary layers. Notable exceptions include blanketing ash sheets, and cross-stratification developed on sloped surfaces. • Principle of Superposition – In an undisturbed sequence, older strata lie below younger strata; a package of sedimentary layers youngs upward. • Principle of Lateral Continuity – A layer of sediment extends laterally in all directions until it naturally pinches out or abuts the walls of its confining basin. -

Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in the Intermountain Region Part 1

United States Department of Agriculture Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in the Intermountain Region Part 1 Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Report Service Research Station RMRS-GTR-375 April 2018 Halofsky, Jessica E.; Peterson, David L.; Ho, Joanne J.; Little, Natalie, J.; Joyce, Linda A., eds. 2018. Climate change vulnerability and adaptation in the Intermountain Region. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-375. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Part 1. pp. 1–197. Abstract The Intermountain Adaptation Partnership (IAP) identified climate change issues relevant to resource management on Federal lands in Nevada, Utah, southern Idaho, eastern California, and western Wyoming, and developed solutions intended to minimize negative effects of climate change and facilitate transition of diverse ecosystems to a warmer climate. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service scientists, Federal resource managers, and stakeholders collaborated over a 2-year period to conduct a state-of-science climate change vulnerability assessment and develop adaptation options for Federal lands. The vulnerability assessment emphasized key resource areas— water, fisheries, vegetation and disturbance, wildlife, recreation, infrastructure, cultural heritage, and ecosystem services—regarded as the most important for ecosystems and human communities. The earliest and most profound effects of climate change are expected for water resources, the result of declining snowpacks causing higher peak winter -

Characterization and Hydraulic Behaviour of the Complex Karst of the Kaibab Plateau and Grand Canyon National Park, USA

Characterization and hydraulic behaviour of the complex karst of the Kaibab Plateau and Grand Canyon National Park, USA CASEY J. R. JONES1, ABRAHAM E. SPRINGER1*, BENJAMIN W. TOBIN2, SARAH J. ZAPPITELLO2 & NATALIE A. JONES2 1School of Earth Sciences and Environmental Sustainability, Northern Arizona University, NAU Box 4099, Flagstaff, AZ 86011, USA 2Grand Canyon National Park, National Park Service, 1824 South Thompson Street, Flagstaff, AZ, 86001, USA *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The Kaibab Plateau and Grand Canyon National Park in the USA contain both shallow and deep karst systems, which interact in ways that are not well known, although recent studies have allowed better interpretations of this unique system. Detailed characterization of sinkholes and their distribution on the surface using geographical information system and LiDAR data can be used to relate the infiltration points to the overall hydrogeological system. Flow paths through the deep regional geological structure were delineated using non-toxic fluorescent dyes. The flow character- istics of the coupled aquifer system were evaluated using hydrograph recession curve analysis via discharge data from Roaring Springs, the sole source of the water supply for the Grand Canyon National Park. The interactions between these coupled surface and deep karst systems are complex and challenging to understand. Although the surface karst behaves in much the same way as karst in other similar regions, the deep karst has a base flow recession coefficient an order of magnitude lower than many other karst aquifers throughout the world. Dye trace analysis reveals rapid, con- duit-dominated flow that demonstrates fracture connectivity along faults between the surface and deep karst. -

Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States Department of Agriculture United States Forest Service

Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States Department of Agriculture United States Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station Daniel G. Milchunas General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-169 April 2006 Milchunas, Daniel G. 2006. Responses of plant communities to grazing in the southwestern United States. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-169. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 126 p. Abstract Grazing by wild and domestic mammals can have small to large effects on plant communities, depend- ing on characteristics of the particular community and of the type and intensity of grazing. The broad objective of this report was to extensively review literature on the effects of grazing on 25 plant commu- nities of the southwestern U.S. in terms of plant species composition, aboveground primary productiv- ity, and root and soil attributes. Livestock grazing management and grazing systems are assessed, as are effects of small and large native mammals and feral species, when data are available. Emphasis is placed on the evolutionary history of grazing and productivity of the particular communities as deter- minants of response. After reviewing available studies for each community type, we compare changes in species composition with grazing among community types. Comparisons are also made between southwestern communities with a relatively short history of grazing and communities of the adjacent Great Plains with a long evolutionary history of grazing. Evidence for grazing as a factor in shifts from grasslands to shrublands is considered. An appendix outlines a new community classification system, which is followed in describing grazing impacts in prior sections. -

Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek The huge outpourings of water at Thunder River, Tapeats Spring, and Deer Spring have attracted people since prehistoric times and today this little corner of Grand Canyon is exceedingly popular among seekers of the remarkable. Like a gift, booming streams of crystalline water emerge from mysterious caves to transform the harsh desert of the inner canyon into absurdly beautiful green oasis replete with the music of falling water and cool pools. Trailhead access can be difficult, sometimes impossible, and the approach march is long, hot and dry, but for those making the journey these destinations represent something close to canyon perfection. Locations/Elevations Mileages Indian Hollow (6250 ft / 1906 m) to Bill Hall Trail Junction (5400 ft / 1647 m): 5.0 mi (8.0 km) Monument Point (7200 ft / 2196 m) to Bill Hall Junction: 2.6 mi (4.2 km) Bill Hall Junction, AY9 (5400 ft / 1647 m) to Surprise Valley Junction, AM9 (3600 ft / 1098 m): 4.5 mi ( 7.2 km) Upper Tapeats Camp, AW7 (2400 ft / 732 m): 6.6 mi ( 10.6 km) Lower Tapeats, AW8 at Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 8.8 mi ( 14.2 km) Deer Creek Campsite, AX7 (2200 ft / 671 m): 6.9 mi ( 11.1 km) Deer Creek Falls and Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 7.6 mi ( 12.2 km) Maps 7.5 Minute Tapeats Amphitheater and Fishtail Mesa Quads (USGS) Trails Illustrated Map, Grand Canyon National Park (National Geographic) North Kaibab Map, Kaibab National Forest (good for roads) Water Sources Thunder River, Tapeats Creek, Deer Creek, and the Colorado River are permanent water sources. -

Grand Canyon

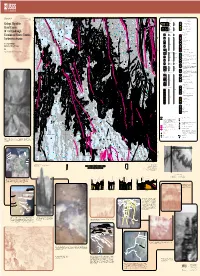

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

USGS General Information Product

Geologic Field Photograph Map of the Grand Canyon Region, 1967–2010 General Information Product 189 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Billingsley, G.H., Goodwin, G., Nagorsen, S.E., Erdman, M.E., and Sherba, J.T., 2019, Geologic field photograph map of the Grand Canyon region, 1967–2010: U.S. Geological Survey General Information Product 189, 11 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/gip189. ISSN 2332-354X (online) Cover. Image EF69 of the photograph collection showing the view from the Tonto Trail (foreground) toward Indian Gardens (greenery), Bright Angel Fault, and Bright Angel Trail, which leads up to the south rim at Grand Canyon Village. Fault offset is down to the east (left) about 200 feet at the rim. -

Pinyon-Juniper Woodland

Historical Range of Variation and State and Transition Modeling of Historic and Current Landscape Conditions for Potential Natural Vegetation Types of the Southwest Southwest Forest Assessment Project 2006 Preferred Citation: Introduction to the Historic Range of Variation Schussman, Heather and Ed Smith. 2006. Historical Range of Variation for Potential Natural Vegetation Types of the Southwest. Prepared for the U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Southwestern Region by The Nature Conservancy, Tucson, AZ. 22 pp. Introduction to Vegetation Modeling Schussman, Heather and Ed Smith. 2006. Vegetation Models for Southwest Vegetation. Prepared for the U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Southwestern Region by The Nature Conservancy, Tucson, AZ. 11 pp. Semi-Desert Grassland Schussman, Heather. 2006. Historical Range of Variation and State and Transition Modeling of Historical and Current Landscape Conditions for Semi-Desert Grassland of the Southwestern U.S. Prepared for the U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Southwestern Region by The Nature Conservancy, Tucson, AZ. 53 pp. Madrean Encinal Schussman, Heather. 2006. Historical Range of Variation for Madrean Encinal of the Southwestern U.S. Prepared for the U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Southwestern Region by The Nature Conservancy, Tucson, AZ. 16 pp. Interior Chaparral Schussman, Heather. 2006. Historical Range of Variation and State and Transition Modeling of Historical and Current Landscape Conditions for Interior Chaparral of the Southwestern U.S. Prepared for the U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Southwestern Region by The Nature Conservancy, Tucson, AZ. 24 pp. Madrean Pine-Oak Schussman, Heather and Dave Gori. 2006. Historical Range of Variation and State and Transition Modeling of Historical and Current Landscape Conditions for Madrean Pine-Oak of the Southwestern U.S. -

A Hiker's Companion to GRAND CANYON GEOLOGY

A Hiker’s Companion to GRAND CANYON GEOLOGY With special attention given to The Corridor: North & South Kaibab Trails Bright Angel Trail The geologic history of the Grand Canyon can be approached by breaking it up into three puzzles: 1. How did all those sweet layers get there? 2. How did the area become uplifted over a mile above sea level? 3. How and when was the canyon carved out? That’s how this short guide is organized, into three sections: 1. Laying down the Strata, 2. Uplift, and 3. Carving the Canyon, Followed by a walking geological guide to the 3 most popular hikes in the National Park. I. LAYING DOWN THE STRATA PRE-CAMBRIAN 2000 mya (million years ago), much of the planet’s uppermost layer was thin oceanic crust, and plate tectonics was functioning more or less as it does now. It begins with a Subduction Zone... Vishnu Schist: 1840 mya, the GC region was the site of an active subduction zone, crowned by a long volcanic chain known as the Yavapai Arc (similar to today’s Aleutian Islands). The oceanic crust on the leading edge of Wyomingland, a huge plate driving in from the NW, was subducting under another plate at the zone, a terrane known as the Yavapai Province. Subduction brought Wyomingland closer and closer to the arc for 150 million years, during which genera- tions of volcanoes were born and laid dormant along the arc. Lava and ash of new volcanoes mixed with the eroded sands and mud from older cones, creating a pile of inter-bedded lava, ash, sand, and mud that was 40,000 feet deep! Vishnu Schist Zoroaster Granite Wyomingland reached the subduction zone 1700 mya. -

Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek The huge outpourings of water at Thunder River, Tapeats Spring, and Deer Spring have attracted people since prehistoric times and today this little corner of Grand Canyon is exceedingly popular among seekers of the remarkable. Like a gift, booming streams of crystalline water emerge from mysterious caves to transform the harsh desert of the inner canyon into absurdly beautiful green oasis replete with the music of water falling into cool pools. Trailhead access can be difficult, sometimes impossible, and the approach march is long, hot and dry, but for those making the journey these destinations represent something close to canyon perfection. Updates and Closures Climbing and/or rappelling in the creek narrows, with or without the use of ropes or other technical equipment is prohibited. This restriction extends within the creek beginning at the southeast end of the rock ledges, known as the “Patio” to the base of Deer Creek Falls. The trail from the river to hiker campsites and points up-canyon remains open. This restriction is necessary for the protection of significant cultural resources. Locations/Elevations Mileages Indian Hollow (6250 ft / 1906 m) to Bill Hall Trail Junction (5400 ft / 1647 m): 5.0 mi (8.0 km) Monument Point (7200 ft / 2196 m) to Bill Hall Junction: 2.6 mi (4.2 km) Bill Hall Junction, AY9 (5400 ft / 1647 m) to Surprise Valley Junction, AM9 (3600 ft / 1098 m): 4.5 mi ( 7.2 km) Upper Tapeats Camp, AW7 (2400 ft / 732 m): 6.6 mi ( 10.6 km) Lower Tapeats, AW8 at Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 8.8 mi ( 14.2 km) Deer Creek Campsite, AX7 (2200 ft / 671 m): 6.9 mi ( 11.1 km) Deer Creek Falls and Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 7.6 mi ( 12.2 km) Maps 7.5 Minute Tapeats Amphitheater and Fishtail Mesa Quads (USGS) Trails Illustrated Map, Grand Canyon National Park (National Geographic) North Kaibab Map, Kaibab National Forest (USDA) Trailhead Access Leave the pavement on Forest Service Road (FSR) 22. -

A 16Th-Century Spanish Inscription in Grand Canyon? a Hypothesis

58 PARK SCIENCE • VOLUME 27 • NUMBER 2 • FALL 2010 Science Feature A 16th-century Spanish inscription in Grand Canyon? A hypothesis By Ray Kenny HE AMAZING JOURNEY OF Francisco Vásquez de Coronado Tis well-known to historians as well as afi cionados of the human history at Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. A handful of Spaniards sent by Coronado from New Mexico fi rst visited the Grand Canyon in September 1540. The story of the fi rst visitation is told in many books and is based upon interpretations from George Parker Winship’s 1892 translation of the accounts of Coronado’s journey written by members of the expedition (De Coronado 1892). As told by Winship in an introduction to the account of Coronado’s journey: It was perhaps on July 4th, 1540 that Coronado drew up his force in front of the fi rst of the “Seven Cities,” and after a sharp fi ght forced his way into the stronghold, the stone and adobe- Spanish conquistador DRAWING BY FREDERIC REMINGTON; PHOTO COPYRIGHT CORBIS built pueblo of Hawikuh, whose ruins can still be traced on a low hillock a few miles southwest of the village now occupied by the New Mexican Zuñi village and returned to Coronado with air line across to the other bank of the Indians. Here the Europeans camped the information he had secured from the stream which fl owed between them. for several weeks. … A small party was Native Americans. Upon learning about sent off toward the northwest, where the news of a large river in the arid lands, The exact location where Cárdenas and another group of seven villages was found.