Translatio and the Constructs of a Roman Nation in Virgil's Aeneid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ovid, Fasti 1.63-294 (Translated By, and Adapted Notes From, A

Ovid, Fasti 1.63-294 (translated by, and adapted notes from, A. S. Kline) [Latin text; 8 CE] Book I: January 1: Kalends See how Janus1 appears first in my song To announce a happy year for you, Germanicus.2 Two-headed Janus, source of the silently gliding year, The only god who is able to see behind him, Be favourable to the leaders, whose labours win Peace for the fertile earth, peace for the seas: Be favourable to the senate and Roman people, And with a nod unbar the shining temples. A prosperous day dawns: favour our thoughts and speech! Let auspicious words be said on this auspicious day. Let our ears be free of lawsuits then, and banish Mad disputes now: you, malicious tongues, cease wagging! See how the air shines with fragrant fire, And Cilician3 grains crackle on lit hearths! The flame beats brightly on the temple’s gold, And spreads a flickering light on the shrine’s roof. Spotless garments make their way to Tarpeian Heights,4 And the crowd wear the colours of the festival: Now the new rods and axes lead, new purple glows, And the distinctive ivory chair feels fresh weight. Heifers that grazed the grass on Faliscan plains,5 Unbroken to the yoke, bow their necks to the axe. When Jupiter watches the whole world from his hill, Everything that he sees belongs to Rome. Hail, day of joy, and return forever, happier still, Worthy to be cherished by a race that rules the world. But two-formed Janus what god shall I say you are, Since Greece has no divinity to compare with you? Tell me the reason, too, why you alone of all the gods Look both at what’s behind you and what’s in front. -

Waters of Rome Journal

TIBER RIVER BRIDGES AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ANCIENT CITY OF ROME Rabun Taylor [email protected] Introduction arly Rome is usually interpreted as a little ring of hilltop urban area, but also the everyday and long-term movements of E strongholds surrounding the valley that is today the Forum. populations. Much of the subsequent commentary is founded But Rome has also been, from the very beginnings, a riverside upon published research, both by myself and by others.2 community. No one doubts that the Tiber River introduced a Functionally, the bridges in Rome over the Tiber were commercial and strategic dimension to life in Rome: towns on of four types. A very few — perhaps only one permanent bridge navigable rivers, especially if they are near the river’s mouth, — were private or quasi-private, and served the purposes of enjoy obvious advantages. But access to and control of river their owners as well as the public. ThePons Agrippae, discussed traffic is only one aspect of riparian power and responsibility. below, may fall into this category; we are even told of a case in This was not just a river town; it presided over the junction of the late Republic in which a special bridge was built across the a river and a highway. Adding to its importance is the fact that Tiber in order to provide access to the Transtiberine tomb of the river was a political and military boundary between Etruria the deceased during the funeral.3 The second type (Pons Fabri- and Latium, two cultural domains, which in early times were cius, Pons Cestius, Pons Neronianus, Pons Aelius, Pons Aure- often at war. -

Roman Architecture with Professor Diana EE Kleiner Lecture 13

HSAR 252 - Roman Architecture with Professor Diana E. E. Kleiner Lecture 13 – The Prince and the Palace: Human Made Divine on the Palatine Hill 1. Title page with course logo. 2. Domus Aurea, Rome, sketch plan of park. Reproduced from Roman Imperial Architecture by John B. Ward-Perkins (1981), fig. 26. Courtesy of Yale University Press. 3. Portrait of Titus, from Herculaneum, now Naples, Archaeological Museum. Reproduced from Roman Sculpture by Diana E. E. Kleiner (1992), fig. 141. Portrait of Vespasian, Copenhagen. Reproduced from A History of Roman Art by Fred S. Kleiner (2007), fig. 9-4. 4. Roman Forum and Palatine Hill, aerial view. Credit: Google Earth. 5. Via Sacra, Rome. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. Arch of Titus, Rome, Via Sacra. Reproduced from Rome of the Caesars by Leonardo B. Dal Maso (1977), p. 45. 6. Arch of Titus, Rome, from side facing Roman Forum [online image]. Wikimedia Commons. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RomeArchofTitus02.jpg (Accessed February 24, 2009). 7. Arch of Titus, Rome, 18th-century painting [online image]. Wikimedia Commons. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:7_Rome_View_of_the_Arch_of_Titus.jpg (Accessed February 24, 2009). Arch of Titus, Rome, from side facing Colosseum. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. 8. Arch of Titus, Rome, attic inscription and triumphal frieze. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. 9. Arch of Titus, Rome, triumphal frieze, victory spandrels, and keystone. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. 10. Arch of Titus, Rome, composite capital. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. 11. Arch of Titus, Rome, triumph panel. Image Credit: Diana E. E. -

Writing Rome

TRAVEL SEMINAR TO ROME JACKIE MURRAY “Writing Rome” (TX201) is a one-credit travel seminar that will introduce students to interdisciplinary perspectives on Rome. “All roads lead to Rome.” This maxim guides our study tour of the Eternal City. In “Writing Rome” students will travel to KAITLIN CURLEY ANDERS, Rome and compare the city constructed in texts with the city constructed of brick, concrete, marble, wood, and metal. This travel seminar will offer tours of the major ancient sites (includ- ing the Fora, the Palatine, the Colosseum, the Pantheon), as well as the Vatican, the major museums, churches and palazzi, Fascist monuments, the Jewish quarter and other locales ripe with the PHOTOS BY: DAN CURLEY, DAN CURLEY, PHOTOS BY: historical and cultural layering that is the city’s hallmark. In addi- OFF-CAMPUS STUDY & EXCHANGES tion, students will keep travel journals and produce a culminat- ing essay (or other written work) about their experiences on the tour, thereby continuing the tradition of writing Rome. WHY ROME? Rome is the Eternal City, a cradle of western culture, and the root of the English word “romance.” Founded on April 21, 753 BCE (or so tradition tells us), the city was the heart of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, and today serves as the capitol of Italy. Creative Thought Matters Bustling, dense, layered, and sublime, Rome has withstood tyrants, invasions, disasters, and the ravages of the centuries. The Roman story is the story of civilization itself, with chapters ? written by citizens and foreigners alike. Now you are the author. COURSE SCHEDULE “Reading Rome,” the 3-credit lecture and discussion-based course, will be taught on the Skidmore College campus during the Spring 2011 semester. -

The Aqua Traiana / Aqua Paola and Their Effects on The

THE AQUA TRAIANA / AQUA PAOLA AND THEIR EFFECTS ON THE URBAN FABRIC OF ROME Carolyn A. Mess A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Architectural History In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Architectural History May 2014 Cammy Brothers __________________ Sheila Crane __________________ John Dobbins __________________ ii ABSTRACT Infrastructure has always played an important role in urban planning, though the focus of urban form is often the road system and the water system is only secondary. This is a misconception as often times the hydraulic infrastructure determined where roads were placed. Architectural structures were built where easily accessible potable water was found. People established towns and cities around water, like coasts, riverbanks, and natural springs. This study isolates two aqueducts, the Aqua Traiana and its Renaissance counterpart, the Aqua Paola. Both of these aqueducts were exceptional feats of engineering in their planning, building techniques, and functionality; however, by the end of their construction, they symbolized more than their outward utilitarian architecture. Within their given time periods, these aqueducts impacted an entire region of Rome that had twice been cut off from the rest of the city because of its lack of a water supply and its remote location across the Tiber. The Aqua Traiana and Aqua Paola completely transformed this area by improving residents’ hygiene, building up an industrial district, and beautifying the area of Trastevere. This study -

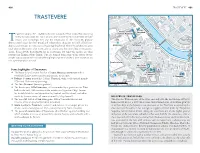

Trastevere (Map P. 702, A3–B4) Is the Area Across the Tiber

400 TRASTEVERE 401 TRASTEVERE rastevere (map p. 702, A3–B4) is the area across the Tiber (trans Tiberim), lying below the Janiculum hill. Since ancient times there have been numerous artisans’ Thouses and workshops here and the inhabitants of this essentially popular district were known for their proud and independent character. It is still a distinctive district and remains in some ways a local neighbourhood, where the inhabitants greet each other in the streets, chat in the cafés or simply pass the time of day in the grocery shops. It has always been known for its restaurants but today the menus are often provided in English before Italian. Cars are banned from some of the streets by the simple (but unobtrusive) method of laying large travertine blocks at their entrances, so it is a pleasant place to stroll. Some highlights of Trastevere ª The beautiful and ancient basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere with a wonderful 12th-century interior and mosaics in the apse; ª Palazzo Corsini, part of the Gallerie Nazionali, with a collection of mainly 17th- and 18th-century paintings; ª The Orto Botanico (botanic gardens); ª The Renaissance Villa Farnesina, still surrounded by a garden on the Tiber, built in the early 16th century as the residence of Agostino Chigi, famous for its delightful frescoed decoration by Raphael and his school, and other works by Sienese artists, all commissioned by Chigi himself; HISTORY OF TRASTEVERE ª The peaceful church of San Crisogono, with a venerable interior and This was the ‘Etruscan side’ of the river, and only after the destruction of Veii by remains of the original early church beneath it; Rome in 396 bc (see p. -

Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 1

Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 1 The following characters are described in the pages that follow the list. Page Order Alphabetical Order Aeolus 2 Achaemenides 8 Neptune 2 Achates 2 Achates 2 Aeolus 2 Ilioneus 2 Allecto 19 Cupid 2 Amata 17 Iopas 2 Andromache 8 Laocoon 2 Anna 9 Sinon 3 Arruns 22 Coroebus 3 Caieta 13 Priam 4 Camilla 22 Creusa 6 Celaeno 7 Helen 6 Coroebus 3 Celaeno 7 Creusa 6 Harpies 7 Cupid 2 Polydorus 7 Dēiphobus 11 Achaemenides 8 Drances 30 Andromache 8 Euryalus 27 Helenus 8 Evander 24 Anna 9 Harpies 7 Iarbas 10 Helen 6 Palinurus 10 Helenus 8 Dēiphobus 11 Iarbas 10 Marcellus 12 Ilioneus 2 Caieta 13 Iopas 2 Latinus 13 Juturna 31 Lavinia 15 Laocoon 2 Lavinium 15 Latinus 13 Amata 17 Lausus 20 Allecto 19 Lavinia 15 Mezentius 20 Lavinium 15 Lausus 20 Marcellus 12 Camilla 22 Mezentius 20 Arruns 22 Neptune 2 Evander 24 Nisus 27 Nisus 27 Palinurus 10 Euryalus 27 Polydorus 7 Drances 30 Priam 4 Juturna 31 Sinon 2 An outline of the ACL presentation is at the end of the handout. Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 2 Aeolus – with Juno as minor god, less than Juno (tributary powers), cliens- patronus relationship; Juno as bargainer and what she offers. Both of them as rulers, in contrast with Neptune, Dido, Aeneas, Latinus, Evander, Mezentius, Turnus, Metabus, Ascanius, Acestes. Neptune – contrast as ruler with Aeolus; especially aposiopesis. Note following sympathy and importance of rhetoric and gravitas to control the people. Is the vir Aeneas (bringing civilization), Augustus (bringing order out of civil war), or Cato (actually -

Early Mythology Ancestry

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY EARLY MYTHOLOGY ANCESTRY 1 INTRODUCTION This book covers the earliest history of man and the mythology in some countries. The beginning from Adam and Eve and their descendants is from the Old Testament, but also by several authors and genealogy programs. The age of the persons in the lineages in Genesis is expressed in their “years”, which has little to do with the reality of our 365-day years. I have chosen one such program as a starting point for this book. Several others have been used, and as can be expected, there are a lot of conflicting information, from which I have had to choose as best I can. It is fairly well laid out so the specific information is suitable for print. In addition, the lineage information shown covers the biblical information, fairly close to the Genesis, and it also leads to both to mythical and historical persons in several countries. Where myth turns into history is up to the reader’s imagination. This book lists individuals from Adam and Eve to King Alfred the Great of England. Between these are some mythical figures on which the Greek (similar to Roman) mythology is based beginning with Zeus and the Nordic (Anglo-Saxon) mythology beginning with Odin (Woden). These persons, in their national mythologies, have different ancestors than the biblical ones. More about the Nordic mythology is covered in the “Swedish Royal Ancestry, Book 1”. Of additional interest is the similarity of the initial creation between the Greek and the Finnish mythology in its national Kalevala epos, from which a couple of samples are included here. -

Ap Latin Summer Assignment

AP LATIN SUMMER ASSIGNMENT: Cardinal Gibbons High School Magistra Crabbe: 2018/2019 Assignment: Read and prepare for a test on Books I, II, IV, VI, VIII, and XII of Virgil’s Aeneid. Directions: ● Carefully read the introduction to the Aeneid written by Bernard Knox, and fill out the corresponding reflection questions. These questions will be collected and graded in August. Content from the introduction will be represented on the test in August. ● Carefully read the English Portions of the Syllabus from Virgil’s Aeneid. This is the entirety of Books I, II, IV, VI, VIII, and XII of Virgil’s Aeneid. Students should read the Revised Penguin Edition by David West. Hard copies of this book are available from Mrs. Crabbe in room 211. ● Fill out the corresponding study questions for each book. In August, these study questions will be collected and graded. ● Students will take a test on these readings before beginning the Latin portion of the AP Syllabus. Index of This Document: Introduction to the Aeneid by Bernard Knox: pp 126 Reading Questions for Introduction: pp 2734 Book I Reading Questions: pp 3543 Book II Reading Questions: pp 4449 Book IV Reading Questions: pp 5056 Book VI Reading Questions: pp 5764 Book VIII Reading Questions: pp 6568 Book XII Reading Questions: pp 6974 Suggested Reading Schedule: May 28th June 1st: Relax this week and recover from your finals. Drink lots of water. Get plenty of sleep. Spend time outside and do something fun with your friends. Help your parents around the house. -

The Political Subtext of Anchises' Speech in Aeneid VI

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects Honors Program 5-2007 Augustus Deified or Denigrated: The Political Subtext of Anchises' Speech in Aeneid VI Scott D. Davis Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Scott D., "Augustus Deified or Denigrated: The Political Subtext of Anchises' Speech in Aeneid VI" (2007). Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. 666. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/666 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUGUSTUS DEIFIED OR DENIGRATED: THE POLITICAL SUBTEXT OF ANCHISES' SPEECH IN AENEID VI by Scott D. Davis Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of HONORS IN UNIVERSITY STUDIES WITH DEPARTMENT HONORS 1Il History Approved: Thesis/Project Advisor Department Honors Advisor Dr. Frances B. Titchener Dr. Susan Shapiro Direcwr, of Hqnors Program vt,u,1~~ D1:JJavidL~~ ' UT AH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT 2007 3 CONTENTS HISTORY CAPSTONE AND SENIOR HONORS THESIS Augustus Deified or Denigrated? The Political Subtext of Anchises' Speech in Aeneid VI. ...... ...... ..... ..... ... ....... ...... ..... ....... ..... .. ...... .4 APPENDIX A Numerical and Graphical Representations of Line Allotments ....... ...... ........ .. ...................... ......... .......... ...... .... .... ......... ....... 36 APPENDIXB Annotated Text of"Parade of Heroes," AeneidVI.756-892 ...... ..................................................................................... 40 APPENDIXC Oral Presentation given at the Conference of the Classical Association of the Middle West and South in Madison Wisconsin , April 2005 ........................................................... -

The Aeneid Virgil

The Aeneid Virgil TRANSLATED BY A. S. KLINE ROMAN ROADS MEDIA Classical education, from a Christian perspective, created for the homeschool. Roman Roads combines its technical expertise with the experience of established authorities in the field of classical education to create quality video courses and resources tailored to the homeschooler. Just as the first century roads of the Roman Empire were the physical means by which the early church spread the gospel far and wide, so Roman Roads Media uses today’s technology to bring timeless truth, goodness, and beauty into your home. By combining excellent instruction augmented with visual aids and examples, we help inspire in your children a lifelong love of learning. The Aeneid by Virgil translated by A. S. Kline This text was designed to accompany Roman Roads Media's 4-year video course Old Western Culture: A Christian Approach to the Great Books. For more information visit: www.romanroadsmedia.com. Other video courses by Roman Roads Media include: Grammar of Poetry featuring Matt Whitling Introductory Logic taught by Jim Nance Intermediate Logic taught by Jim Nance French Cuisine taught by Francis Foucachon Copyright © 2015 by Roman Roads Media, LLC Roman Roads Media 739 S Hayes St, Moscow, Idaho 83843 A ROMAN ROADS ETEXT The Aeneid Virgil TRANSLATED BY H. R. FAIRCLOUGH BOOK I Bk I:1-11 Invocation to the Muse I sing of arms and the man, he who, exiled by fate, first came from the coast of Troy to Italy, and to Lavinian shores – hurled about endlessly by land and sea, by the will of the gods, by cruel Juno’s remorseless anger, long suffering also in war, until he founded a city and brought his gods to Latium: from that the Latin people came, the lords of Alba Longa, the walls of noble Rome. -

College Study Tours

College Study Tour s ITALY | THE GRAND TOUR Art, history, culture, fashion, food—in one boot-shaped package—Italy of the international leader in World Heritage Sites. Wander through the seems to have it all. With all of the time you could possibly need, you winding cobbled streets of Venice, and on to Florence where the plazas can now experience all of its grandeur in one epic tour. could compete with the world’s best museums. Relax like an Assisiani in small-time Assisi, and like a southerner in magnificent Sorrento. On this top-to-bottom journey, you’ll squeeze every last drop out of Italy Internalize the eerie quiet of ancient Pompeii, and in the city once known on a whirlwind 10-day adventure, savoring the balanced, well-aged as Caput Mundi—Latin for “head of the world”—see clamoring traffic flavors of some of history’s best years. You’ll have to kick up the pace a juxtaposed against some of the world’s most timeless sites. bit, but the tradeoff is an unparalleled lens on the beauty and excitement Venice (2) Pisa Florence (2) Assisi (1) Rome (2 or 4) Pompeii Capri Sorrento (1) efcollegestudytours.com/gtia | 877-485-4184 Day 1: Fly to Italy destination. Enjoy an island cruise and visit the Gardens Meet your group and travel on an overnight flight to Venice. of Augustus. Those who do not go on the excursion will INCLUDED ON TOUR: enjoy free time in the Sorrento region. Day 2: Venice Round-trip flights on major carriers Arrive in Venice: Welcome to Venice, the “Floating City.” Day 9: Sorrento Region | Rome Depending on your arrival time, you may have free time to Travel to Rome: When you arrive in Rome, share a pizza settle in and explore the city on your own.