The Enduring Mythological Role of the Anonymous Source Deep Throat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Begin Video Clip

C-SPAN FIRST LADIES/JACQUELINE KENNEDY May 09, 2014 9:56 a.m. ET (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) JACQUELINE KENNEDY: And I think every first lady should do something in this position to help the things she cares about. I just think that everything in the White House should be the best -- the entertainment that's given here. The art of children is the same the world over. And so, of course, is our feeling for children. I think it is good in a world where there's quite enough to divide people, that we should cherish the language and emotion that unite us all. (END VIDEO CLIP) SUSAN SWAIN: Jacqueline Kennedy's 1,000 days as first lady were defined by images -- political spouse, young mother, fashion icon, advocate for the arts. As television came of age, it was ultimately the tragic images of President Kennedy's assassination and funeral that cemented Jacqueline Kennedy in the public consciousness. Good evening and welcome to C-SPAN's series "First Ladies: Influence and Image.” Tonight, we'll tell you the story of the wife of the 35th president of the United States, named Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy. And we have two guests at the table for the next two hours to tell you more about her life story. Michael Beschloss, presidential historian, author of many books on the presidency, and has a special focus over the years on the Cold War era and the Kennedy administration. Thanks for being here. MICHAEL BESCHLOSS: Pleasure. SWAIN: Barbara Perry is a UVA political scientist and as part of the "Modern First Ladies" series at the University of Kansas has written a Jacqueline Kennedy biography. -

Woodward and Bernstein, Dynamic Duo, Together Again By

Woodward and Bernstein, Dynamic Duo, Together Again By ALESSANDRA STANLEY years later the news media haven't highest level branches of govern- the Republican National Committee It was like Simon sitting down with changed that much. It's the political ment was eroding and journalists' in 1973 when the Watergate scandal Garfunkel or Sonny returning to climate that has dramatically al- credibility was on the rise. was reaching its peak.) Cher. Woodward and Bernstein were tered. President Bush couldn't be luck- Not surprisingly, perhaps, Fox sitting side by side, openly discussing And that was the most striking im- ier. Now, respect for the news media News paid less attention to the reve- the identity of Deep Throat. Starting age of the whole Watergate reunion. has rarely been lower, and the one lation than other 24-hour news net- on the "Today" show, and wending Two journalists famous for protect- major investigative piece conducted works. Mr. Bernstein and Mr. Wood- their way from "Good ing a confidential government source during his re-election campaign by ward were on CNN but not on Fox. The Morning America" to were being celebrated at the same CBS News was botched, because Dan "When The Washington Post put moment that two other journalists, Rather's report that Mr. Bush used them on low-rated cable news net- TV "Larry King Live," the two Watergate report- Matt Cooper of Time magazine and family connections to get in — and works first, we decided to pass," the Watch ers basked in the relief Judith Miller of The New York around — the Texas National Guard network's spokesman, Paul Schur, and reflected glory of Times are facing possible jail time relied on fake documents. -

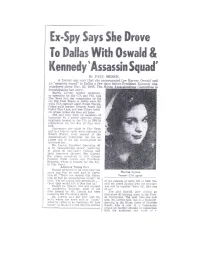

Ex-Spy Says She Drove to Dallas with Oswald & Kennedy 'Assassin

Ex-Spy Says She Drove To Dallas With Oswald & Kennedy 'Assassin Squad' By PAUL MESKIL A former spy says that she accompanied Lee Harvey Oswald and an "assassin squad" to Dallas a few days before President Kennedy was murdered there Nov. 22, 1963. The House Assassinations Committee is investigating her story. Marita Lorenz, former undercov- er operative for the CIA and FBI, told The News that her companions on the car trip from Miami to Dallas were Os. wald, CIA contract agent Frank Sturgis, Cuban exile leaders Orlando Bosch and Pedro Diaz Lanz, and two Cuban broth- ers whose names she does not know. She said they were all members of Operation 40, a secret guerrilla group originally formed by the CIA in 1960 in preparation for the Bay of Pigs inva- sion. Statements she made to The News and to a federal agent were reported to Robert Blakey, chief counsel of the Assassinations Committee. He has as- signed one of his top investigators to interview her. Ms. Lorenz described Operation 40 as an ''assassination squad" consisting of about 30 anti-Castro Cubans and their American advisers. She claimed the group conspired to kill Cuban Premier Fidel Castro and President Kennedy, whom it blamed for the Bay of Pigs fiasco. Admitted Taking Part Sturgis admitted in an interview two years ago that he took part in Opera- Maritza Lorenz tion 40. "There are reports that Opera- Farmer CIA agent tion 40 had an assassination squad." he said. "I'm not saying that personally ... In the summer or early fall of 1963. -

The Watergate Story (Washingtonpost.Com)

The Watergate Story (washingtonpost.com) Hello corderoric | Change Preferences | Sign Out TODAY'S NEWSPAPER Subscribe | PostPoints NEWS POLITICS OPINIONS BUSINESS LOCAL SPORTS ARTS & GOING OUT JOBS CARS REAL RENTALS CLASSIFIEDS LIVING GUIDE ESTATE SEARCH: washingtonpost.com Web | Search Archives washingtonpost.com > Politics> Special Reports 'Deep Throat' Mark Felt Dies at 95 The most famous anonymous source in American history died Dec. 18 at his home in Santa Rosa, Calif. "Whether ours shall continue to be a government of laws and not of men is now before Congress and ultimately the American people." A curious crime, two young The courts, the Congress and President Nixon refuses to After 30 years, one of reporters, and a secret source a special prosecutor probe release the tapes and fires the Washington's best-kept known as "Deep Throat" ... the burglars' connections to special prosecutor. A secrets is exposed. —Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox after his Washington would be the White House and decisive Supreme Court firing, Oct. 20, 1973 changed forever. discover a secret taping ruling is a victory for system. investigators. • Q&A Transcript: John Dean's new book "Pure Goldwater" (May 6, 2008) • Obituary: Nixon Aide DeVan L. Shumway, 77 (April 26, 2008) Wg:1 http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/special/watergate/index.html#chapters[6/14/2009 6:06:08 PM] The Watergate Story (washingtonpost.com) • Does the News Matter To Anyone Anymore? (Jan. 20, 2008) • Why I Believe Bush Must Go (Jan. 6, 2008) Key Players | Timeline | Herblock -

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum Wilderness Years (1962 – 1968) Collection

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum Wilderness Years (1962 – 1968) Collection Series I: Correspondence Sub-Series A: Alphabetical Box 1-39: Correspondence Files. 1963-1965. Sorted. (PPS 238) Box 40-48: Correspondence Files. 1966-1968. Sorted. (PPS 230) Sub-Series B: Social and Political Correspondence Box 1-6: Correspondence Files. Form and guide letters. 1960-1968. (PPS 243) Box 7-10: Correspondence File. Form Letter Answers. (PPS 231) Box 11-13: Correspondence Files. Outgoing correspondence files. ca. June 1961-Oct. 1962. (PPS 245) Box 14-21: Correspondence Files. Various files – Social and political correspondence. 1965- 1968. (PPS 247) Box 22-25: Correspondence Files. Anne Volz Higgins Personal, Social, Political Correspondence. 1967. (PPS 248) Box 26-32: Correspondence Files. Secretaries source file, Ann V. Higgins – form letters (1964- 1968). Materials compiled in three 3-ring notebooks. (PPS 250) Correspondence Files. Mailing lists and campaign thank yous. (PPS 250A) Box 33- :Correspondence Files. 1960-1968 Campaigns. X (extra) copies. – Arranged alphabetically. (PPS 246) Sub-Series C: Appearances and Invitations Box 1-4: Correspondence. Correspondence re: Appearances, Contributions, and Interviews. (PPS 227) Box 5: Correspondence relating to RN’s 1961-1962 schedule: California invitations, turn downs, and pending. (PPS 228) Box 6: Correspondence File. 1960-1964. (PPS 232) Box 7-14: Correspondence Files. Speaking invitations and turn downs. 1963-1967. (PPS 237) Box 15-18: Correspondence re: invitations. 1963-1967. Arranged by State (PPS 234) Box 19-20: Correspondence. College speaking invitations. 1963-1967. (PPS 229) Sub-Series D: Law Firms Box 1: Correspondence: Adams, Duque & Hazeltine (PPS 238) Box 2: Correspondence. 1963. -

The Impartiality Paradox

The Impartiality Paradox Melissa E. Loewenstemt The constitutional principles that bind our free society instruct that the American people must "hold the judgeship in the highest esteem, that they re- gard it as the symbol of impartial, fair, and equal justice under law."'1 Accord- ingly, in contrast with the political branches, the Supreme Court's decisions "are legitimate only when [the Court] seeks to dissociate itself from individual 2 or group interests, and to judge by disinterested and more objective standards." As Justice Frankfurter said, "justice must satisfy the appearance of justice. 3 Almost instinctively, once a President appoints a judge to sit on the Su- preme Court,4 the public earmarks the Justice as an incarnation of impartiality, neutrality, and trustworthiness. Not surprisingly then, Presidents have looked to the Court for appointments to high profile and important committees of national concern. 5 It is among members of the judiciary that a President can find individuals certain to obtain the immediate respect of the American people, and often the world community. It is a judge's neutrality, fair-mindedness, and integrity that once again label him a person of impartiality and fairness, a per- son who seeks justice, and a President's first choice to serve the nation. The characteristics that led to a judge's initial appointment under our adversary sys- tem, and which lend themselves to appearances of propriety and justice in our courts, often carry over into extrajudicial activities as well. As Ralph K. Winter, Jr., then a professor at the Yale Law School, stated: [t]he appointment of a Justice of the Supreme Court to head a governmental com- mission or inquiry usually occurs because of the existence of a highly controversial issue which calls for some kind of official or authoritative resolution ....And the use of Supreme Court Justices, experience shows, is generally prompted by a presi- t Yale Law School, J.D. -

John Greenewald, Jr., Creator Of: the Black Vault

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION FOI/PA DELETED PAGE INFORMATION SHEET FOI/PA# 1212526-0 Total Deleted Page(s) = 12 Page 30 - Referral/Consult; Page 31 - Referral/Consult; Page 50 - Referral/Direct; Page 51 - Referral/Direct; Page 52 - Referral/Direct; Page 53 - Referral/Direct; Page 54 - Referral/Direct; Page 55 - Referral/Direct; Page 56 - Referral/Direct; Page 57 - Referral/Direct; Page 58 - Referral/Direct; Page 59 - Referral/Direct; xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx X Deleted Page(s) X X No Duplication Fee X X For this Page X xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx P'7,,____y =___ E!:)-36 (Rev. 11-17-88) ~- FBI TRANSMIT VIA: PRECEDENCE: CLASSIFICATION:• 0 Teletype 0 Immediate 0 TOP SECRET 0 Facsimile 0 Priority 0 SECRET !KJ AIRTEL 0 Routine 0 CONFIDENTIAL 0 UNCLAS E F T 0 0 UNCLAS Date 11/19/92 INVEST DIV, DOMESTIC TERRORISM UNIT b6 (2 MM-61560) (FCI-1) (P) b7C ,..;; b6 aka - I I b7C AL; OF 0 I ( Reference FBIHQ te1ca1l to Miami 11/17/92. Enclosed for FBIHQ are three copies of a sel~ explanatory LHM suitable for dissemination. Per referenced telcall advising of DOJ authority, Miami has initiated a Neutrality case on captioned matter. b6 ~~~~~~lis a well known anti-Castro activist in the Miami b7c ____The following is a descrigtion o~ NAME RACE b6 __{jJ__ SEX.* = DOB b7Cc=J ~ -~ SSAN All INFORMATION CONTAINED "i"LA DL HEREIN IS UNCLASSIFIED. -

Journalism, Intelligence and the New York Times: Cyrus L

Matthew Jones Journalism, intelligence and The New York Times: Cyrus L. Sulzberger, Harrison E. Salisbury and the CIA Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Jones, Matthew (2015) Journalism, intelligence and The New York Times: Cyrus L. Sulzberger, Harrison E. Salisbury and the CIA. History. 100 (340). pp. 229-250. ISSN 0018-2648 ISSN DOI: 10.1111/1468-229X.12096 © 2014 The Author. History © 2014 The Historical Association and John Wiley & Sons Ltd This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/60486/ Available in LSE Research Online: December 2014 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Journalism, intelligence and The New York Times: Cyrus L. Sulzberger, Harrison E. Salisbury and the CIA In early June 1966, Cyrus L. Sulzberger, the renowned former Chief Foreign Correspondent of The New York Times – a Pulitzer Prize winner fifteen years before, friend to numerous world leaders, and a confidant of Charles de Gaulle - met Dean Acheson, the ex-US Secretary of State, to discuss the problems facing the Western Alliance precipitated by France’s recent departure from the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. -

{PDF EPUB} the Poetry of Richard Milhous Nixon by Richard M. Nixon Four Poems by Richard Milhous Nixon

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Poetry of Richard Milhous Nixon by Richard M. Nixon Four Poems by Richard Milhous Nixon. Abraham Lincoln, John Quincy Adams, and Jimmy Carter all published collections of poetry—and I don’t mean to diminish their stately, often tender contributions to arts and letters by what follows. But the simple fact of the matter is, their poetical efforts pale in comparison to Richard Nixon, who was, and remains, the most essential poet-president the United States of America has ever produced. The Poetry of Richard Milhous Nixon , a slim volume compiled by Jack S. Margolis and published in 1974, stands as a seminal work in verse. Comprising direct excerpts from the Watergate tapes—arguably the most fecund stage of Nixon’s career—it fuses the rugged rhetoric of statesmanship to the lithe contours of song, all rendered in assured, supple, poignant free verse. Below, to celebrate Presidents’ Day, are four selections from this historic chapbook, which has, lamentably, slipped out of print. THE POSITION The position is To withhold Information And to cover up This is Totally true. You could say This is Totally untrue. TOGETHER We are all In it Together. We take A few shots And It will be over. Don’t worry. I wouldn’t Want to be On the other side Right now. IN THE END In the end We are going To be bled To death. And in the end, It is all going To come out anyway. Then you get the worst Of both worlds. The power of Nixon’s poems was duly recognized by his peers—other writers, most notably Thomas Pynchon, have used them as epigraphs. -

Sinclair 2016

GOLDEN AGE HEROES: THE AMERICAN MYTH OF WOODWARD AND BERNSTEIN A Senior Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American Studies By Lauren Louise Sinclair Washington, D.C. April 27, 2016 GOLDEN AGE HEROES: THE AMERICAN MYTH OF WOODWARD AND BERNSTEIN Lauren Louise Sinclair Thesis Adviser: Professor Brian Hochman, Ph. D. ABSTRACT The Watergate scandal of the 1970s is one of the greatest presidential scandals in American history. In an elaborate scheme in quest for more power, President Richard Nixon and his administration performed unconstitutional acts of corruption while in the White House. These acts were brought to the public by the media and the investigative reporting done on the scandal. Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward are two of the most famous investigative journalists in American history due to their work on the scandal at The Washington Post. After the scandal had passed and Richard Nixon resigned from his presidency, Woodward and Bernstein wrote a book in 1974 telling of their experience reporting on Watergate titled All the President’s Men. This book was then made into an iconic film in 1976. The release of the book and film created a narrative of the two reporters as heroic journalists and propelled them into the public eye and popular culture. Woodward and Bernstein became poster children of investigative journalism, and my research aims to highlight the portrayal of the David and Goliath archetype applied to the journalists reporting the wrongdoings of the Nixon administration. -

Observations on the Rise of the Appellate Litigator

Observations on the Rise of the Appellate Litigator Thomas G. Hungar and Nikesh Jindal* I. INTRODUCTION........................................................................511 II. THE EMERGENCE OF A PRIVATE APPELLATE BAR ...................512 III. The Reasons Behind the Development of a Private Appellate Bar..........................................................................517 A. Appellate Practices as a Response to Modern Law Firm Economics ..............................................................518 B. Increasing Sophistication Among Clients About the Need for High-Quality Appellate Representation ...........523 C. The Increasing Stakes of Civil Litigation........................525 D. A Changing Supreme Court ............................................527 IV. SKILLS OF AN EFFECTIVE APPELLATE LAWYER.......................529 V. CONCLUSION ...........................................................................536 I. INTRODUCTION Over the last few decades, there has been a noticeable increase in the visibility and prominence of appellate litigators in the private bar. Most of the attention has focused on Supreme Court advocacy, where certain private law firms and lawyers have developed reputations for specialized expertise and experience in 1 briefing and arguing cases before the Court, but the phenomenon extends to other federal and state court appeals as well. The practice of law as a whole is becoming increasingly specialized, and the trend in appellate litigation is no exception, although it appears to be a more recent occurrence than the growth of substantive speciali- * Thomas G. Hungar is a partner at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP and Co- Chair of the firm’s Appellate and Constitutional Law Practice Group. He previously served as Deputy Solicitor General of the United States. Nikesh Jindal is an associate at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP and a member of the firm’s Litigation Department and of the Administrative Law and Regulatory and White Collar Defense and Investigations Practice Groups. -

Cbcopland on The

THE UNITED STATES ARMY FIELD BAND The Legacy of AARON COPLAND Washington, D.C. “The Musical Ambassadors of the Army” rom Boston to Bombay, Tokyo to Toronto, the United States Army Field Band has been thrilling audiences of all ages for more than fifty years. As the pre- mier touring musical representative for the United States Army, this in- Fternationally-acclaimed organization travels thousands of miles each year presenting a variety of music to enthusiastic audiences throughout the nation and abroad. Through these concerts, the Field Band keeps the will of the American people behind the members of the armed forces and supports diplomatic efforts around the world. The Concert Band is the oldest and largest of the Field Band’s four performing components. This elite 65-member instrumental ensemble, founded in 1946, has performed in all 50 states and 25 foreign countries for audiences totaling more than 100 million. Tours have taken the band throughout the United States, Canada, Mexico, South America, Europe, the Far East, and India. The group appears in a wide variety of settings, from world-famous concert halls, such as the Berlin Philharmonie and Carnegie Hall, to state fairgrounds and high school gymnasiums. The Concert Band regularly travels and performs with the Sol- diers’ Chorus, together presenting a powerful and diverse program of marches, over- tures, popular music, patriotic selections, and instrumental and vocal solos. The orga- nization has also performed joint concerts with many of the nation’s leading orchestras, including the Boston Pops, Cincinnati Pops, and Detroit Symphony Orchestra. The United States Army Field Band is considered by music critics to be one of the most versatile and inspiring musical organizations in the world.