CTX (Combating Terrorism Exchange), V.4:3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afghan National Security Forces Getting Bigger, Stronger, Better Prepared -- Every Day!

afghan National security forces Getting bigger, stronger, better prepared -- every day! n NATO reaffirms Afghan commitment n ANSF, ISAF defeat IEDs together n PRT Meymaneh in action n ISAF Docs provide for long-term care In this month’s Mirror July 2007 4 NATO & HQ ISAF ANA soldiers in training. n NATO reaffirms commitment Cover Photo by Sgt. Ruud Mol n Conference concludes ANSF ready to 5 Commemorations react ........... turn to page 8. n Marking D-Day and more 6 RC-West n DCOM Stability visits Farah 11 ANA ops 7 Chaghcharan n ANP scores victory in Ghazni n Gen. Satta visits PRT n ANP repels attack on town 8 ANA ready n 12 RC-Capital Camp Zafar prepares troops n Sharing cultures 9 Security shura n MEDEVAC ex, celebrations n Women’s roundtable in Farah 13 RC-North 10 ANSF focus n Meymaneh donates blood n ANSF, ISAF train for IEDs n New CC for PRT Raising the cup Macedonian mid fielder Goran Boleski kisses the cup after his team won HQ ISAF’s football final. An elated team-mate and team captain Elvis Todorvski looks on. Photo by Sgt. Ruud Mol For more on the championship ..... turn to page 22. 2 ISAF MIRROR July 2007 Contents 14 RC-South n NAMSA improves life at KAF The ISAF Mirror is a HQ ISAF Public Information product. Articles, where possible, have been kept in their origi- 15 RAF aids nomads nal form. Opinions expressed are those of the writers and do not necessarily n Humanitarian help for Kuchis reflect official NATO, JFC HQ Brunssum or ISAF policy. -

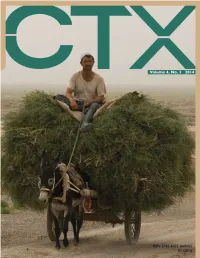

CTX Volume 4 No 3

August 2014 EDITORIAL STAFF From the Editor MICHAEL FREEMAN Executive Editor This issue begins with a familiar landscape: the eastern border area of Afghani- ANNA SIMONS Executive Editor stan, specifically the Paktika valley region. Major Mike Hutchinson gives a per- ELIZABETH SKINNER Managing Editor sonal account of the work he and his team, ODA 3325, did to dislodge the Taliban RYAN STUART Design & Layout from an area considered to be one of their strongholds. In the process, not only was the team able to defeat the insurgents militarily, but more importantly, EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD they found a way to reverse the trend of economic decay that years of fighting VICTOR ASAL had brought to the population. Following this article is a thoughtful discussion University at Albany SUNY by Captain Caleb Slayton of the ways in which U.S. military education about ALEJANDRA BOLANOS Islam falls short of its goal of preparing operators to effectively and respectfully National Defense University navigate within the Muslim world. The urge to fit Muslims into “good” and “bad” categories through coded language, he tells us, is doing a serious disservice LAWRENCE CLINE to both Islam and our forces. Naval Postgraduate School STEPHEN DI RIENZO Up next is Julia McClenon, who describes the devastating effects that official National Intelligence University discrimination and injustice are having on the indigenous Uyghur population SAJJAN GOHEL in Xinjiang Province in western China. From McClenon’s perspective (she has been living and working in China), Xinjiang represents a living primer on Asia Pacific Foundation how to drive an oppressed people to terrorist violence. -

Afghanistan Bibliography 2019

Afghanistan Analyst Bibliography 2019 Compiled by Christian Bleuer Afghanistan Analysts Network Kabul 3 Afghanistan Analyst Bibliography 2019 Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN), Kabul, Afghanistan This work is licensed under this creative commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode The Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN) is a non-profit, independent policy research organisation. It aims to bring together the knowledge, experience and drive of a large number of experts to better inform policy and to increase the understanding of Afghan realities. It is driven by engagement and curiosity and is committed to producing independent, high quality and research-based analysis on developments in Afghanistan. The institutional structure of AAN includes a core team of analysts and a network of contributors with expertise in the fields of Afghan politics, governance, rule of law, security, and regional affairs. AAN publishes regular in-depth thematic reports, policy briefings and comments. The main channel for dissemination of these publications is the AAN web site: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/ Cover illustration: “City of Kandahar, with main bazaar and citadel, Afghanistan.” Lithograph by Lieutenant James Rattray, c. 1847. Coloured by R. Carrick. TABLE OF CONTENTS Bibliography Introduction and Guide ..................................................................... 6 1. Ethnic Groups ................................................................................................... -

AFGHANISTAN D Qurghonteppa TAJIKISTAN Kerki (Kurgan-Tyube) Mary

C A m H 64 u 66 68 70 72 Mur 74 H ° D ° ° ° a-ye ° gho ° ar y b INA ya UZBEKISTAN r INA a AFGHANISTAN D Qurghonteppa TAJIKISTAN Kerki (Kurgan-Tyube) Mary Kiroya iz M rm Dusti Khorugh u e BADAKHSHAN r T g a Keleft Rostaq FayzFayzabad Abad b ir Qala-I-Panjeh Andkhvoy Jeyretan am JAWZJAN P Mazar-e-Sharif KUNDUZ TaluqanTaloqan Jorm TURKMENISTAN Shiberghan Kunduz h Eshkashem s Dowlatabad BALKH Kholm Khanabad TAKHAR u T K e d Baghlan Farkhar 36 z ° h Shulgarah e u 36 n Sari Pul Aybak Dowshi ° d y Maymana g BAGHLAN h SAMANGAN n Gilgit s u FARYAB Tokzar i G ISLAMIC Qeysar PANJSHER H AFGHANISTAN r Gushgy a SARI PUL Bazarak n u Jammu BADGHIS Mahmud-e- NURISTAN K Towraghondi Raqi ns Taybad oru KUNAR Mo Chaharikar N P and Qala-e-Naw rghab BAMYAN KAPISA A PARWAN M Asad Abad Mehtarlam Dowlat Bamyan H HiratHerat Chaghcharan Yar G Kashmir H Karokh A ar Owbeh Maydan Kabul ir L Jalalabad ud Shahr KABUL 34 WARDAK Mardan REPUBLIC REPUBLIC ° NANGARHAR 34 GHOR DAY LOGAR K ° HERATHIRAT h y Pul-e-Alam b Peshawar KUNDI Peywar Pass e Islamabad r d P an ass Nili lm Gardez He Ghazni Rawalpindi PAKTYA KHOST Shindand- GHAZNI Qarah Bagh Khost (Matun) Bannu Anar Darreh Khas Uruzgan Sharan PAKISTAN b a URUZGAN d n FARAH a ut gh ar Now Zad Ar H Farah Tirin Kot PAKTIKA OF OF h 32 ra ZABUL h a Kajaki ra ° F u 32 m k L Tank ° a Qalat a -e Delar rn d Ta w Ro h Lashkar Gah IRAN as National capital Kh Kandahar s Zhob u Provincial capital Kadesh d Zabol n I Town, village The boundaries and names shown and the designations HILMAND used on this map do not imply official endorsement or Zaranj Spin Buldak INDI ✈ Airports Chaman acceptance by the United Nations. -

SCO Membership Rich Ancient Culture of Central and Raoof Hassan, the Head of an Is- Making Processes and Using Reli- Perience and Religious Arguments West Asia

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:X Issue No:73 Price: Afs.15 www.afghanistantimes.af www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimeswww.twitter.com/ afghanistantimes SUNDAY . OCTOBER 11 . 2015 -Mizan 19, 1394 HS Britain fears Keep 10,000 indiscriminate troops in Page 4 attacks on Afghanistan: Westerners in US presidential Bangladesh hopeful KABUL: A Republican presiden- tial candidate has called for keep- US is an ing at least 10,000 troops in Af- immigrant ghanistan to help the local forces and combat terrorists. Marco Ru- nation, bio wrote in an opinion piece for Page 5 should wel- Abdul Zuhoor Qayomi to probe fall of Kunduz city to on President Muhammad Ashraf the USA Today: The war, which the Taliban. Internal Security Ghani and Chief Executive Offic- many mistakenly believed would come refu- KABUL: The Wolesi Jirga on Sat- Committee (ISC) of the Wolesi er (CEO) Abdullah Abdullah to end in a matter of weeks, has last- gees: Kerry urday asked the government to Jirga said that security forces af- review the military operations ed far longer than anyone expect- review its anti-militants opera- ter 12 days operations failed to against militants in Kunduz. A ed. The senator from Florida said tions in northern Kunduz prov- weed the militants out of Kunduz delegation comprised of lawmak- the Afghans, besides fighting ince. The lawmakers criticized province. It said that lack of coor- ers from different provinces and against a brutal enemy, had to deal clearance operations of Afghan se- dination among security forces is members of ISC and Defense with enduring challenges, includ- G20 curity forces in Kunduz and said one of the big challenge in this re- Committee of the Wolesi Jirga ing drug lords who had the coun- endorses that the offensive should be prop- gard. -

Nuanced Diplomacy in Zerok, Afghanistan

JULY 2008 . VOL 1 . ISSUE 8 After Action Report: tribe. Two sub-tribes in Zerok make up was also engaged. This time, the enemy the population base of the district. The was able to kill two ANA soldiers and Nuanced Diplomacy in people subsist on farming and small damage several vehicles. Zerok, Afghanistan trade. The district is approximately 33 square miles and sits just 12 miles from I immediately met with the elders, shura By Captain John G. Gibson, U.S. Army the Pakistan border. members, the district governor and the ANP chief at the Zerok District Center. enemy machine gun fire and Rocket Corruption and collusion were the I discussed security, governance and Propelled Grenades (RPGs) slammed into bedrock of Taliban operations focused development in the district. I asked the my convoy as two tracer rounds punched on the destabilization of Zerok district. shura members if they knew anything through the turret of my up armored The first three weeks of my deployment about the enemy forces operating in vehicle. My third firefight in four days consisted of several operations designed the area. The entire room responded and the summer was only starting. It was to simply assess the environment with a resounding “no.” Frustrated by mid-June 2007 in the mountains of the and create relationships with local the response, I reminded the group that sprawling Paktika Province. I quickly district leaders, Afghan National jobs and economic development were realized that the enemy knew my name, impossible without security. number of vehicles, departure times and “The members of the shura plans; I had just left a meeting with its I moved my entire convoy element back informants, the Zerok tribal shura. -

Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity

JULY 2008 . VOL 1 . ISSUE 8 Recent Highlights in on their positions. The fighters also June 18, 2008 (JORDAN): A Jordanian mined roads leading into the Taliban military court sentenced Ziad Khalaf Terrorist Activity occupied villages, which were seized on Raja al-Karbouly, an Iraqi al-Qa`ida June 16. – AFP, June 17 operative, to death for planning terrorist June 16, 2008 (UNITED STATES): attacks on Jordanians in Iraq. According The U.S. government designated June 17, 2008 (AFGHANISTAN): Four to an AP report, “The ruling was the the Philippines-based group Rajah British soldiers were killed in an second time the court had sentenced al- Solaiman Movement (RSM) as “specially explosion in Lashkar Gah, Helmand Karbouly to death in the case. Following designated global terrorists.” The Province. The Taliban took credit for the initial verdict in March 2007, a decision will freeze the assets of RSM the operation. – CNN, June 18 Jordanian Appeals Court asked military and its leaders. On June 4, the United judges to retry him to verify his claims Nations had previously declared that June 17, 2008 (PHILIPPINES): The that he suffered a mental illness.” – AP, the RSM was linked to al-Qa`ida. Abu Sayyaf Group released well-known June 18 – Bloomberg, June 16 journalist Ces Drilon, her cameraman and a university professor, all of whom June 18, 2008 (THAILAND): A roadside June 16, 2008 (IRAQ): Four bombs had been held hostage since June 8. They bomb ripped through a police vehicle in targeting homes and vehicles of Iraqi were freed on Jolo Island. The hostages Pattani Province, killing a police colonel security force members detonated recounted their experience, saying that and his driver. -

Who Is Who in the Pakistani Taliban: a Sampling of Insurgent

PROGRAM FOR CULTURE & CONFLICT STUDIES 1 Who is Who in the Pakistani Taliban: A Sampling of Insurgent Personalities in Seven Operational Zones in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Area (FATA) and North Western Frontier Province Taliban influence in the FATA in 2009. Source BBC Following the U.S.-led attack against Afghanistan in October 2001, Taliban sympathizers in Pakistan’s western tribal areas quickly pledged support and provided additional manpower and resources to help the Afghan Taliban resistance. The Pashtun tribes who dominate the western tribal agencies of Pakistan share ancestral lineages with many of Afghanistan’s Pashtun tribesman and both have long resisted colonial attempts of occupation. Even in a modern context, the core of the Afghan resistance movement against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan was based in these same areas, using Peshawar as a de facto capital and the tribal agency’s of North NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL PROGRAM FOR CULTURE & CONFLICT STUDIES 2 and South Waziristan as training areas and key junctions for transiting personnel and weapons into Afghanistan. The network ties that emerged following the Taliban’s ouster in 2001 between Pakistani militants and Afghan Taliban members are nothing new. The initial flow of Taliban fighters into the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) became a tidal wave following the collapse of the Taliban regime in Kandahar and after the monumental battle of Tora Bora in December 2001 and the subsequent spring 2002 battle of the Shah-i-khot Valley (Operation Anaconda). Along with the Taliban came hundreds of fleeing Arab and foreign fighters linked to al-Qaeda, many of whom settled among their Pashtun supporters and sympathizers in North and South Waziristan. -

2012 Consolidated Appeal for Afghanistan

SAMPLE OF ORGANIZATIONS PARTICIPATING IN CONSOLIDATED APPEALS CRS AARREC CWS Humedica MENTOR TGH ACF DanChurchAid IA MERLIN UMCOR ACTED DDG ILO Muslim Aid UNAIDS ADRA Diakonie Emerg. Aid IMC NCA UNDP Africare DRC INTERMON NPA UNDSS AMI-France EM-DH Internews NRC UNEP ARC FAO INTERSOS OCHA UNESCO ASB FAR IOM OHCHR UNFPA ASI FHI IPHD OXFAM UN-HABITAT AVSI FinnChurchAid IR PA UNHCR CARE FSD IRC PACT UNICEF CARITAS GAA IRD PAI UNIFEM CEMIR International GOAL IRIN Plan UNJLC CESVI GTZ IRW PMU-I UNMAS CFA GVC Islamic Relief Première Urgence UNOPS CHF Handicap JOIN RC/Germany UNRWA CHFI International JRS RCO VIS CISV HealthNet TPO LWF Samaritan's Purse WFP CMA HELP Malaria Consortium Save the Children WHO CONCERN HelpAge Malteser SECADEV World Concern COOPI International Mercy Corps Solidarités World Relief CORDAID HKI MDA SUDO WV COSV Horn Relief MDM TEARFUND ZOA HT MEDAIR Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 Humanitarian Dashboard ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Table I. Requirements per cluster ......................................................................................................... 8 Table II. Requirements per priority level ............................................................................................... 8 Table III. Requirements per organization ......................................................................................................... -

CTC Sentinel 1(8)

JULY 2008 . VOL 1 . ISSUE 8 COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER AT WEST POINT CTC Sentinel OBJECTIVE . RELEVANT . RIGOROUS Contents Why Terrorists Quit: Gaining FEATURE ARTICLE From Al-Qa`ida’s Losses 1 Why Terrorists Quit: By Michael Jacobson Gaining From Al-Qa`ida’s Losses By Michael Jacobson REPORTS 4 An Ideological and Operational Threat: Abu `Amr/Shaykh `Isa By Erich Marquardt & Abdul Hameed Bakier 8 Indonesia’s Approach to Jihadist Deradicalization By Kirsten E. Schulze 10 The High Stakes Battle for the Future of Musa Qala By David C. Isby 13 Al-Qa`ida Seeking to Recruit African- American Muslims By Cadets Benjamin Haas & Daniel McGrory 15 Propaganda and Peace Deals: The Taliban’s Information War in Pakistan By Arthur Keller 18 Uncovering Extremist Violence in Morocco Jordanians protest the 2005 Amman hotel bombings, an operation that created divisions among al-Qa`ida’s supporters. By Alison Pargeter 21 After Action Report: Nuanced n recent months, there has been the radical group Hizb al-Tahrir3 (also Diplomacy in Zerok, Afghanistan a spate of seemingly good news spelled Hizb-ut-Tahrir) established the By Captain John G. Gibson, U.S. Army in the counter-terrorism arena, Quilliam Foundation, which describes as former terrorist leaders and itself as “Britain’s first Muslim counter- 23 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity Iclerics have renounced their previous extremism think tank.”4 28 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts beliefs. Former Egyptian Islamic Jihad head Sayyid Imam al-Sharif (also known While these are clearly positive as Dr. Fadl), -

7, 72 ENG 557Cp.2

UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONERFOR REFUGEES R 7, 72 ENG 557cp.2 , PRELIMINARY REPORT ON CONDITIONS AFFECTING THE 'REPATRIATION OF AFGHAN REFUGEES Prepared by: Richard English, Ph.D For the Operational Lnit for Repatriation tc Afghanistan l;NHCR, Geneva 20 June D83 1A Be not so sweet that they swallow you. Be not so bitter that they spityou out. -- Pushtun proverb The views presented in this reportare those of the author and should not be construedas representing the official position or policy of the United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees. CONCLLSION 36 REFERENCES 58 ANNEX I/TABLES 59 ANNEX II /POLITICAL PARTIES 7, ANNEX III CROSS -BORDER AGENCIES & COMMITTEES OF COOPERATION 78 ANNEX IG/DIRECTORY OF NGOS 37 MAPS 1. Major Ethnic Groups of Afghanistan 3 2. Percentage of Refugees in Iran & Pakistan 12 Originating in Each Province of Afghanistan 3. Location of Afghan Refugee Camps in NWFP 4. Location of Afghan Refugee Camps in Baluchistan 5. Approximate Locations of Internally Displaced 14 Populations in Afghanistan 6. Crossing Points for Afghan Refugees 23 Returning to Afghanistan 7 Relief Map of Afghanistan with Planning 34 Regions Indicated 8 Planning Regions 33 Map of individual regions followpp. 33, 39, 42, 49,33 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1. Project Background 5 2. Objectives 3. The Report 4. Acknowledgements BACKGROUND 1. Population 6 2. Economy and Subsistence 10 3. Consequenses of the War ii - - Agriculture 11 - - Refugees in Pakistan 12 - - Refugees in Iran 13 - - The Internally Displaced 14 - - The Resistance _ .14 4. Prospects for Repatriation. 13 UNHCR .CONCERNS AND ACTIVITIES /AFGHANISTAN ti... -

08 August 2017

IOM - Humanitarian Assistance Programme Weekly Activity Report Week Starting Date Week Ending Date Period: 02 –August-17 08-August-17 Submission Date: 08-August-17 Cumulative Highlights01 January to 08 August 2017 # of Provinces # of ND # of Joint # of Report- # of Report- # of Houses # of Houses # of Houses # of Individu- # of Individu- # of Verified # of Verified # of Families # of Individ- Affected incidents Assessments ed Affected ed Affected Completely Severely Moderately als Deaths als Injured Affected Affected Assisted by uals Assisted Reported Families Individuals Destroyed Damaged Damaged Families Individuals IOM by IOM 33 233 496 14,857 104,036 1,702 4,515 1,229 116 95 6,786 43,315 5,021 35,147 2016 vs 2017 Analysis Weekly Highlights 02-08 August 2017 # of Provinces # of ND # of Joint # of Report- # of Report- # of Houses # of Houses # of Houses # of Individu- # of Individu- # of Verified # of Verified # of Families # of Individ- Affected incidents Assessments ed Affected ed Affected Completely Severely Moderately als Deaths als Injured Affected Affected Assisted by uals Assisted Reported Families Individuals Destroyed Damaged Damaged Families Individuals IOM by IOM 1 3 3 10 70 0 10 0 0 0 10 70 19 133 Natural Disasters, Coordination and DRR activity UPDATE: 02-08 August 2017 Paktika: As per initial reports obtained from ANDMA on 28 July, as a result of flood; 45 families were reportedly affected in Orgon, Zerok and Gayan district. The flood mainly impacted crops, orchards and agriculture lands with few houses reportedly partially damaged. Access is still not possible to the Zerok and Gayan due to security concerns.