Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 ACS PUMS DATA DICTIONARY August 7, 2015 HOUSING RECORD

2011 ACS PUMS DATA DICTIONARY August 7, 2015 HOUSING RECORD RT 1 Record Type H .Housing Record or Group Quarters Unit SERIALNO 7 Housing unit/GQ person serial number 0000001..9999999 .Unique identifier DIVISION 1 Division code 0 .Puerto Rico 1 .New England (Northeast region) 2 .Middle Atlantic (Northeast region) 3 .East North Central (Midwest region) 4 .West North Central (Midwest region) 5 .South Atlantic (South region) 6 .East South Central (South region) 7 .West South Central (South Region) 8 .Mountain (West region) 9 .Pacific (West region) PUMA 5 Public use microdata area code (PUMA) 00100..08200 .Public use microdata area codes 77777 .Combination of 01801, 01802, and 01905 in Louisiana Note: Public use microdata areas (PUMAs) designate areas of 100,000 or more population. Use with ST for unique code. REGION 1 Region code 1 .Northeast 2 .Midwest 3 .South 4 .West 9 .Puerto Rico ST 2 State Code 01 .Alabama/AL 02 .Alaska/AK 04 .Arizona/AZ 05 .Arkansas/AR 06 .California/CA 08 .Colorado/CO 09 .Connecticut/CT 10 .Delaware/DE 11 .District of Columbia/DC 12 .Florida/FL 13 .Georgia/GA 1 15 .Hawaii/HI 16 .Idaho/ID 17 .Illinois/IL 18 .Indiana/IN 19 .Iowa/IA 20 .Kansas/KS 21 .Kentucky/KY 22 .Louisiana/LA 23 .Maine/ME 24 .Maryland/MD 25 .Massachusetts/MA 26 .Michigan/MI 27 .Minnesota/MN 28 .Mississippi/MS 29 .Missouri/MO 30 .Montana/MT 31 .Nebraska/NE 32 .Nevada/NV 33 .New Hampshire/NH 34 .New Jersey/NJ 35 .New Mexico/NM 36 .New York/NY 37 .North Carolina/NC 38 .North Dakota/ND 39 .Ohio/OH 40 .Oklahoma/OK 41 .Oregon/OR 42 .Pennsylvania/PA 44 .Rhode -

Contributions to Regional Haze in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic States

Contributions to Regional Haze in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic United States Mid-Atlantic/Northeast Visibility Union (MANE-VU) Contribution Assessment Prepared by NESCAUM For the Mid-Atlantic/Northeast Visibility Union (MANE-VU) Figure III-21 2002 Annual Average PM 2.5 , Sulfate, Nitrate and Total Carbon for MANE-VU based on IMPROVE and STN data. Mass data are supplemented by the FRM network AIRS vs. CMAQ in PA,MD,DE,DC,VA,WV,NC during August 9~16, 2002 100 O3 hourly 75 O3 daytime hourly O3 diurnal max 50 O3 daily mean 15%/35% Fractional Error (%) . (%) Error Fractional 25 30%/50% 60%/75% 0 -75 -50 -25 0 25 50 75 Fractional Bias (%) Contribution to PM Sulfate in Brigantine, NJ Surface Emission + All Canada & Mexico PA Emission 11.2% 30% OH Other US Elevated 9.2% Emission 1.9% NY 4.3% RI VT WV 0.0% 0.0% 4.1% DC CONTRIBUTION OF RPO TO PM SO4 IN CLASS I AREAS 0.0% ME MD MANE-VU LADCO VISTAS CenRAP0.1% Esurface 4.0% AR VA 100 NH MS 0.2% 4.0% 90 0.3% IN 0.3% SC MI 80 AL GA KY 3.9% CT TX 0.9% DE 2.9% LA 1.2% 2.2% NJ 70 0.5% 0.7% 1.6% 2.0% 0.3% NC 3.5% 60 TN IL IA MA WI 2.9% 50 MN MO 1.6% 2.2% 0.6% 1.0% 1.3% Percent 40 0.5% 0.9% 30 20 10 0 Brigantine, NJ Acadia, ME Lye Brook, VT Shenandoah, VA August 2006 Members of NESCAUM Board Arthur Marin, Executive Director NESCAUM Anne Gobin, Bureau Chief Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Air Management James P. -

Caribbean Billfish Project?

Image by sportfishimages.com What is the Caribbean Billfish Project? The goal of the Caribbean Billfish Project (CBP) is to recapture lost wealth and contribute to sustainable livelihoods in the West- ern Central Atlantic region through investment in economically, technically and ecologically feasible billfish fisheries management and conservation approaches. The objective is to develop business plans for one or more long-term pilot projects aimed at sustain- able management and conservation of billfish within the Western Central Atlantic Ocean. The CBP has 4 components: 1. Generating value and conservation outcomes through innovative management. 2. Strengthening regional billfish management and conservation planning. 3. A Functional and Responsive Consortium on Billfish Management and Conservation (CBMC). 4. Business plans developed for pilot investments in sustainable management and conservation of billfish. 2 • Caribbean Billfish Project List of Acronyms CBMC Consortium on Billfish Management and Conservation CFMC Caribbean Fisheries Management Council CI Conservation International CNFO Caribbean Network of Fisherfolk Organizations CRFM Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism FAD Fish Aggregating Devices GGFA Grenada Game Fishing Association ICCAT International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas IUU Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated IGFA International Game Fish Association OSPESCA Central America Fisheries and Aquaculture Organization RFMO Regional Fisheries Management Organization RFB Regional Fisheries Body WECAFC Western -

About MANE-VU.Pmd

ABOUT Mid-Atlantic/Northeast MANE-VU Visibility Union FACT SHEET Regional haze is air pollution that visually obscures mountain ranges, city skylines and scenic vistas. With regional haze diminishing pristine views of the Nation’s national parks and wilderness areas, visi- tors may not experience the beauty seen in the past. Regional haze also poses risks to human health. An organization called MANE-VU, a coalition of air quality experts from nearly 20 federal, state and tribal agencies, is working to develop solutions to bring back beautiful vistas to the Mid-Atlantic and North- east regions. MANE-VU, the Mid-Atlantic/Northeast Visibility Union, includes representatives from Connecticut, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, the Penobscot Indian Nation, Rhode Island, St. Regis Mohawk Tribe, Ver- mont, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and the National Park Service. The federal Clean Air Act requires EPA to address impaired visibility caused by haze in federal Class I areas – certain national parks and wilderness areas. In 1999 EPA issued the Regional Haze Rule, which requires states and interested tribes to take steps to reduce haze-causing emissions from numerous sources over large geographic areas. In accordance with the Rule, all states in the na- tion are required to identify key sources of haze- causing pollution, develop plans to reduce emis- sions from those sources, and submit these plans to EPA by 2008. EPA established five regional planning organizations across the nation to coor- dinate this effort. -

Deep Structure of the Atlantic Margins and Neighboring Oceanic Crust from Wide-Angle Seismic Data and Plate Kinematic Reconstructions

Deep structure of the Atlantic margins and neighboring oceanic crust from wide-angle seismic data and plate kinematic reconstructions. Frauke Klingelhoefer, Youssef Biari, Dieter Franke, Thomas Funck, Lies Loncke, Jean-Claude Sibuet, Christophe Basile, James Austin, Caesar Rigoti, Mohamed Sahabi, Massinissa Benabdellouahed, and Walter Roest This study Biari et al., 2021 Rotational poles Matthews et al., 2016 Volcanic provinces Whittaker et al., 2015 Marginal plateaus Loncke et al., 2020 Click to visit Conclusions Next slide Central Atlantic (~195 Ma) Initial extension Assymmetric seafloor spreading Accretion of thin oceanic crust Funck et al., 2004 Biari et al., 2015 Biari et al., 2017 ● 37 km unthinned continental crust thickness ● No indications for the existence of serpentinized upper mantle material ● 150 km broad region with serpentinized upper mantle material exhumed to the seafloor ● Oceanic crust of 7–8 km thickness ● ~3 thin oceanic crust ● Unthinned continental crust has a thickness of ~36 km South Atlantic – Falkland Segment (~160Ma) Schimschal and Jokat, 2019 Falkland Plateau comprises three regions: ● the Falkland/Malvinas islands (underlain by a 35 km crust of continental origin) ● the Falkland Plateau basin (underlain by thick oceanic crust) ● the Maurice Ewing Bank (28 km thick continental fragment heavily overprinted by magmatic intrusions) South Atlantic – Austral Segment (~133 Ma) Schnabel et al., 2008 Hirsch et al., 2009 ● 20–25 km of thinned continental crust ● Continental crust thinning from 40 to 15 km below the SDR ● One single thick SDR complex ● Further thinning crust seaward of SDR. ● Up to 10 km thick underplate layers at the ● High velocity lower crustal body transition zone interpreted to be igneous material. -

The Atlantic Northeast Region and the French Canada

Outline The Atlantic Northeast and French Canada 1. The Atlantic Northeast 2. French Canada and Overarching Themes Atlantic Northeast Atlantic Northeast Defining the Region Defining the Region • What’s the unique characteristic? • Less explicit than other unique characteristics • The “New England Question” • Character, rurality, not French, relatively What’s the author doing on p. 104? limited resources on land, relatively rich • adjacent ocean, very early settlement • Do you agree with the argument? • Region defined by bordering regions, but has own character Atlantic Northeast Atlantic Northeast Economic Struggles Economic Struggles • “Suffered longer and more continually from physical geography disadvantages economic handicaps than any other on the • continent” • soils are poor • Why? • growing season is short and cool Atlantic Northeast Atlantic Northeast • growing season • the time period each year when dominant crops can be grown • climate and crop selection • days between first and last frost • extremely important statistic for agriculture http://epaedia.eea.europa.eu/page.php?pid=343#gallery Atlantic Northeast Atlantic Northeast Economic Struggles Economic Struggles • physical geography (site) disadvantages physical geography (site) advantages- soils are poor • • turned-disadvantages growing season is short and cool • • fish stock mineral resources are scarce • • water power resources not sufficient • second-growth timber grows slowly Atlantic Northeast Atlantic Northeast Economic Struggles Economic Struggles • lower income per capita -

Contributions to Regional Haze in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic United States: Preliminary Update Through 2007

Contributions to Regional Haze in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic United States: Preliminary Update Through 2007 Mid-Atlantic/Northeast Visibility Union (MANE-VU) Updated Contribution Assessment Prepared by Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management (NESCAUM) for the Mid-Atlantic/Northeast Visibility Union (MANE-VU) March 2012 Members of Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management Arthur Marin, Executive Director Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management Anne Gobin, Bureau Chief Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection, Bureau of Air Management Melanie Loyzim, Bureau Director Maine Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Air Quality Nancy Seidman, Deputy Assistant Commissioner Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Waste Prevention Craig Wright, Acting Director New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services, Air Resources Division William O’Sullivan, Director New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Office of Air Quality Management David Shaw, Director New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Air Resources Douglas L. McVay, Chief Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, Office of Air Resources Richard A. Valentinetti, Director Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation, Air Pollution Control Division Contributions to Regional Haze in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic United States: Preliminary Update Through 2007 Mid-Atlantic/Northeast Visibility Union (MANE-VU) Updated Contribution Assessment Prepared by Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management (NESCAUM) for the Mid-Atlantic/Northeast Visibility Union (MANE-VU) March 2012 ii CONTRIBUTIONS TO REGIONAL HAZE IN THE NORTHEAST AND MID-ATLANTIC UNITED STATES: PRELIMINARY UPDATE THROUGH 2007 MID-ATLANTIC/NORTHEAST VISIBILITY UNION (MANE-VU) UPDATED CONTRIBUTION ASSESSMENT Project Manager Paul Miller, NESCAUM Principal Contributors Leiran Biton, NESCAUM Printed: April 2015 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

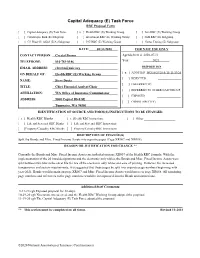

Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force RBC Proposal Form

Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force RBC Proposal Form [ ] Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force [ x ] Health RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Life RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Catastrophe Risk (E) Subgroup [ ] Investment RBC (E) Working Group [ ] SMI RBC (E) Subgroup [ ] C3 Phase II/ AG43 (E/A) Subgroup [ ] P/C RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Stress Testing (E) Subgroup DATE: 08/31/2020 FOR NAIC USE ONLY CONTACT PERSON: Crystal Brown Agenda Item # 2020-07-H TELEPHONE: 816-783-8146 Year 2021 EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] DISPOSITION [ x ] ADOPTED WG 10/29/20 & TF 11/19/20 ON BEHALF OF: Health RBC (E) Working Group [ ] REJECTED NAME: Steve Drutz [ ] DEFERRED TO TITLE: Chief Financial Analyst/Chair [ ] REFERRED TO OTHER NAIC GROUP AFFILIATION: WA Office of Insurance Commissioner [ ] EXPOSED ________________ ADDRESS: 5000 Capitol Blvd SE [ ] OTHER (SPECIFY) Tumwater, WA 98501 IDENTIFICATION OF SOURCE AND FORM(S)/INSTRUCTIONS TO BE CHANGED [ x ] Health RBC Blanks [ x ] Health RBC Instructions [ ] Other ___________________ [ ] Life and Fraternal RBC Blanks [ ] Life and Fraternal RBC Instructions [ ] Property/Casualty RBC Blanks [ ] Property/Casualty RBC Instructions DESCRIPTION OF CHANGE(S) Split the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets into separate pages (Page XR007 and XR008). REASON OR JUSTIFICATION FOR CHANGE ** Currently the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets are included on page XR007 of the Health RBC formula. With the implementation of the 20 bond designations and the electronic only tables, the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets were split between two tabs in the excel file for use of the electronic only tables and ease of printing. However, for increased transparency and system requirements, it is suggested that these pages be split into separate page numbers beginning with year-2021. -

REPORT of the 2020 PORBEAGLE SHARK STOCK ASSESSMENT MEETING (Online, 15-22 June2020)

PORBEAGLE STOCK ASSESSMENT MEETING - ONLINE 2020 REPORT OF THE 2020 PORBEAGLE SHARK STOCK ASSESSMENT MEETING (Online, 15-22 June2020) The results, conclusions and recommendations contained in this Report only reflect the view of the Sharks Species Group. Therefore, these should be considered preliminary until the SCRS adopts them at its annual Plenary meeting and the Commission revise them at its Annual meeting. Accordingly, ICCAT reserves the right to comment, object and endorse this Report, until it is finally adopted by the Commission. 1. Opening, adoption of agenda and meeting arrangements The Chair opened the meeting by expressing his gratitude for attendees’ interest and participation. He reminded the Group that the meeting’s objectives were to assemble and review all available information on porbeagle sharks, assess the status of porbeagle sharks, and update any information from research projects. On behalf of the Executive Secretary the Assistant Executive Secretary welcomed the participants. The Group agreed to adopt the agenda (Appendix 1). The list of participants is included in Appendix 2. The list of papers and presentations is in Appendix 3 and the abstracts provided by the authors are in Appendix 4. Rapporteurs were assigned to the agenda sections as follows: Sections Rapporteur Item 1 N.G. Taylor Item 2 J. Carlson, A. Domingo, C. Palma, M. Ortiz, Y. Semba, R. Forselledo, C. Santos, R. Coelho, F. Mas Item 3 E. Cortes, X. Zhang, H. Bowlby, L.G. Cardoso, and N.G. Taylor Item 4 H. Bowlby, N.G. Taylor, E. Cortés, Y. Semba, E. Babcock Item 5 A. Domingo, N. Duprey, and C. -

Atlantic Northeast Coastal Monitoring Summit New England Center Durham, NH December 10-12, 2002 Barry Burgan, USEPA

APPENDIX C Presentations from December 10, 2002 [This page intentionally left blank] Mr. Barry Burgan EPA Opening Remarks and Charge to Workshop [This page intentionally left blank] Atlantic Northeast Coastal Monitoring Summit New England Center Durham, NH December 10-12, 2002 Barry Burgan, USEPA Atlantic Northeast Coastal Monitoring Summit Welcome ! Charge Logistics Atlantic Northeast Coastal Monitoring Summit Meeting Charge: – Identify value-added integration of selected monitoring program elements to make better management decisions – Identify monitoring gaps and methods to fill them – Identify research needed to support region’s monitoring agenda Atlantic Northeast Coastal Monitoring Summit Leading Management issues: –Habitat –Nutrients –Contaminants Atlantic Northeast Coastal Monitoring Summit Set the stage: – Federal Initiatives (CWAP, NSTC) – National Coastal Assessment – GoM Action Plan – Ocean Commission interest in integration – GoMOOS- real time monitoring Atlantic Northeast Coastal Monitoring Summit Integration- Key word – Pilot – Eliminate Stove-pipes – Strengthen environmental monitoring – Starting point- don’t expect to complete in two days! We invited you because you can make the technical and management decisions and make this happen Atlantic Northeast Coastal Monitoring Summit How do we use the time together to build a regional monitoring framework? – We want you to actively participate – Forget past experiences with similar efforts – Leave preconceptions at the door – Stay open minded, use constructive reasoning -

00 RGA Marcellus Utica Profile Cover 2014.09.04.Cdr

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SERVICES FOR THE MARCELLUS AND UTICA SHALE GAS INDUSTRIES Cultural Resource Consultants DBE/WBE/SBE Certified RGA, Inc. Cultural Resource Consultants www.rgaincorporated.com RGA, Inc. (Richard Grubb & Associates) was established in 1988 as a full-service cultural resource management firm and has since grown to become one of the largest independent archaeological and historic preservation consulting companies in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast regions. The firm is DBE/WBE/SBE certified and has 39 full time professionals on staff. RGA has successfully completed over 450 energy sector projects in compliance with federal and state regulations for new substation and electric transmission lines, natural gas pipelines, and for Marcellus and Utica shale gas gathering lines and facilities. RGA Projects: Over 5,000 in 17 states RGA Energy Projects: Over 450 in 8 states RGA has developed innovative systems to effectively manage concurrent surveys and reporting for large-scale, time- sensitive energy projects. Presently our team of experts continues to support one of the largest mid-stream Marcellus shale gas companies in northeastern Pennsylvania. Our regional expertise in Marcellus and Utica shale gas infrastructure projects is broad and includes comprehensive knowledge of the natural and regulatory landscape, Native American and historic contexts, geomorphology, logistical challenges, and landowner and municipal concerns. Please contact us at one of our locations or e-mail Alice Domm at [email protected]. New -

Wildfire Retrofit Guide Mid-Atlantic/Northeast

mid-ATLantic/norTHEAST EDITION mid-ATLantic/norTHEAST Protect Your Property from Wildfire Table of contents 3 Introduction 4 Mid-Atlantic/Northeast Retrofit Guide 15 Property Assessment Checklist 4 PROTECT YOUR PROPERTY FROM WILDFIRE YOU CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE Periods of drought combined with increased populations in areas, such as the Atlantic Coastal Pine Barrens that cover 6,200 square miles of the coastal plain of New Jersey, Long Island in New York, and Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket in Massachusetts, and the high-density forests of the Western Piedmont, present an unpredictable danger of wildfires in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the country. As these areas are threatened by potentially larger and more destructive fires, property owners are looking for solutions to reduce the risk of damage to houses and businesses. This guide was created for the states of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia and West Virginia. It takes into account regional building styles and construction materials, common topographical characteristics and other risk factors identified by fire science research. While wildfire protection begins with the individual, this research proves that a community-wide approach to fire protection is the most effective, so please share this guide with neighbors and friends. If something combustible is located within a 100-foot perimeter of your house or business (including your neighbor’s house, business, surroundings or landscaping), it could potentially increase your risk of wildfire damage. Everyone benefits from a wildfire-adaptive community. Wildfire research has shown that individuals and families can protect their houses and businesses against wildfires by addressing three clear sources of vulnerability: the house or business itself, the landscaping nearby and the general vegetation in the area surrounding the structure.