Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Types of Dance Styles

Types of Dance Styles International Standard Ballroom Dances Ballroom Dance: Ballroom dancing is one of the most entertaining and elite styles of dancing. In the earlier days, ballroom dancewas only for the privileged class of people, the socialites if you must. This style of dancing with a partner, originated in Germany, but is now a popular act followed in varied dance styles. Today, the popularity of ballroom dance is evident, given the innumerable shows and competitions worldwide that revere dance, in all its form. This dance includes many other styles sub-categorized under this. There are many dance techniques that have been developed especially in America. The International Standard recognizes around 10 styles that belong to the category of ballroom dancing, whereas the American style has few forms that are different from those included under the International Standard. Tango: It definitely does take two to tango and this dance also belongs to the American Style category. Like all ballroom dancers, the male has to lead the female partner. The choreography of this dance is what sets it apart from other styles, varying between the International Standard, and that which is American. Waltz: The waltz is danced to melodic, slow music and is an equally beautiful dance form. The waltz is a graceful form of dance, that requires fluidity and delicate movement. When danced by the International Standard norms, this dance is performed more closely towards each other as compared to the American Style. Foxtrot: Foxtrot, as a dance style, gives a dancer flexibility to combine slow and fast dance steps together. -

Lh/1/0512 Lindy Hop – Rules

LH/1/0512 LINDY HOP – RULES 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 In all items, not regulated separately in the following, the appropriate conditions stipulated by the WRRC especially in the Tournament Rules shall be applicable. 1.2 Lindy Hop must remain free to allow evolution of the dance. Lindy Hop is danced to Swing music. Lindy Hop is based on 6 and 8 counts. Lindy Hop belongs to Lindy Hoppers. Lindy Hop shall give priority to musical interpretation There are NO syllabus for Lindy Hop 1.3 All competitors in WRRC tournaments must arrive and report to the tournament directors at least one hour prior to the beginning of the event. The specific required arrival time shall be stated in the tournament announcement. 1.4 The concept for Lindy Hop events arranged within the World Rock ‘n’ Roll Confederation is a smaller form of event where the audience, the dancers and the dance should be in focus. The competition should be arranged in a social context, the audience, participators and officials should have the possibility to dance and enjoy the spirit of Lindy Hop. There is no need for a huge arena like concepts and in coherence with Lindy Hop spirit the event can be arranged in Clubs, Theaters and smaller forms of arenas where the audiences can come close to the dancers and the joy and happiness that the dance spreads. The events should preferably be arranged together with other type of Swing dances. 1.5 LINDY HOP TOURNAMENTS Age Age music music music (bars/min) Duration of Duration of Speed of the the of Speed Juniors 8-17 1:30 50 Main Class Min. -

Balboa West Coast 6:30 Pm to 7:30 Pm a Closed Position Dance of RUEDA This Style of Swing Is California’S Official State Dance $18 Per Person Quick and Fancy Footwork

Erin and Tami are sisters who have co-owned and operated PBDA since 1983, making this our 37th year! If you have never danced Swing before, start here! Calling all hepcats! This is the original 1930s ”Savoy” style Swing – This 6-count style of Swing was all the rage in the ’40s Join our classes and enjoy our Saturday night up-tempo with Charleston movements, kicks, and character – and ’50s – up-tempo with an easy basic step. Swing dances featuring some of the best it’s the most show-stopping style! This dance is still very popular the world over. Swing bands in the country. Instructor: Erin Stevens Instructor: Tami Stevens It’s a proven fact that dancing promotes health Saturday Mornings ADVANCED STEPS & STYLINGS Monday Nights Sunday Afternoons and happiness – come join the fun! Starting: Feb. 22nd Saturday Afternoons Starting: Feb. 24th Starting: Feb. 23rd Six Week Series – $90 Starting: Feb. 22nd Six Week Series – $90 SAVE THE DATE…on Memorial Day Six Week Series – $90 LEVEL I: 10:00 am to 11:00 am Six Week Series – $90 LEVEL I: 7:15 to 8:15 pm LEVEL I: 4:15 pm to 5:15 pm Weekend, May 23–24, we will be hosting LEVEL II: 11:00 am to 12:00 pm LEVEL III: 12:00 pm to 1:00 pm LEVEL II: 8:15 to 9:15 pm LEVEL II: 5:15 pm to 6:15 pm Instructor: Tami Stevens a Swing Camp in honor of World Lindy Easy dips and flourishes to finish Hop Day (and Frankie Manning’s birthday). -

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice. -

2018/19 Hip Hop Rules & Regulations

2018/19 Hip Hop Rules for the New Zealand Schools Hip Hop Competition Presented by the New Zealand Competitive Aerobics Federation 2018/19 Hip Hop Rules, for the New Zealand Schools Hip Hop Championships © New Zealand Competitive Aerobic Federation Page 1 PART 1 – CATEGORIES ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 NSHHC Categories .............................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Hip Hop Unite Categories .................................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 NSHHC Section, Division, Year Group, & Grade Overview ................................................................................ 3 1.3.1 Adult Age Division ........................................................................................................................................ 3 1.3.2 Allowances to Age Divisions (Year Group) for NSHHC ................................................................................ 4 1.4 Participation Limit .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Part 2 – COMPETITION REQUIREMENTS ........................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Performance Area ............................................................................................................................................. -

Urban Street Dance Department

Urban Street Dance Department Divisions and Competition Rules Break Dance Division Urban Street Dance Division Implemented by the WADF Managing Committee January 2020 Artistic Dance Departments, Divisions and Competition Rules WADF Managing Committee Nils-Håkan Carlzon President Irina Shmalko Stuart Saunders Guido de Smet Senior Vice President Executive Secretary Vice President Marian Šulc Gordana Orescanin Roman Filus Vice President Vice President Vice President Page 2 Index Artistic Dance Departments, Divisions and Competition Rules Urban Street Dance Department Section G-2 Urban Street Dance Division Urban Street Dance Competitions Urban Street Urban Street Dance is a broad category that includes a variety of urban styles. The older dance styles that were created in the 1970s include up-rock, breaking, and the funk styles. At the same time breaking was developing in New York, other styles were being created in California. Several street dance styles created in California in the 1970s such as roboting, bopping, hitting, locking, bustin', popping, electric boogaloo, strutting, sac-ing, and dime-stopping. It is historically inaccurate to say that the funk styles were always considered hip-hop. "Hip-Hop Dance" became an umbrella term encompassing all of these styles. Tempo of the Music: Tempo: 27 - 28 bars per minute (108 - 112 beats per minute) Characteristics and Movement: Different new dance styles, such as Quick Popping Crew, Asian style, African style, Hype Dance, New-Jack-Swing, Popping & Locking, Jamming, etc., adding creative elements such as stops, jokes, flashes, swift movements, etc. Some Electric and Break movements can be performed but should not dominate. Floor figures are very popular but should not dominate the performance. -

Cross‐Cultural Perspectives on the Creation of American Dance 1619 – 1950

Moore 1 Cross‐Cultural Perspectives on the Creation of American Dance 1619 – 1950 By Alex Moore Project Advisor: Dyane Harvey Senior Global Studies Thesis with Honors Distinction December 2010 [We] need to understand that African slaves, through largely self‐generative activity, molded their new environment at least as much as they were molded by it. …African Americans are descendants of a people who were second to none in laying the foundations of the economic and cultural life of the nation. …Therefore, …honest American history is inextricably tied to African American history, and…neither can be complete without a full consideration of the other. ‐‐Sterling Stuckey Moore 2 Index 1) Finding the Familiar and Expressions of Resistance in Plantation Dances ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 6 a) The Ring Shout b) The Cake Walk 2) Experimentation and Responding to Hostility in Early Partner Dances ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 14 a) Hugging Dances b) Slave Balls and Race Improvement c) The Blues and the Role of the Jook 3) Crossing the Racial Divide to Find Uniquely American Forms in Swing Dances ‐‐‐‐‐‐ 22 a) The Charleston b) The Lindy Hop Topics for Further Study ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 30 Acknowledgements ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 31 Works Cited ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 32 Appendix A Appendix B Appendix C Appendix D Moore 3 Cross‐Cultural Perspectives on the Creation of American Dance When people leave the society into which they were born (whether by choice or by force), they bring as much of their culture as they are able with them. Culture serves as an extension of identity. Dance is one of the cultural elements easiest to bring along; it is one of the most mobile elements of culture, tucked away in the muscle memory of our bodies. -

Musica House Dance 2014

Musica house dance 2014 The Best New Best Dance Music || Electro & House Dance Club Mix || Vol (Electro House. Best dance music new electro house The latest in electronic dance music. Get the latest from. The Best Electronic Dance Music Sessions (Electro House, Progressive House, Tech House, EDM). Always. Best Dance Music Electro House Dance Club Mix. ▻More Free Music: See als our. Best Dance Music Electro House Dance Club Mix Tracklist: 1. Phunk Investigation - Let The Bass Kick. More Videos from Best Dance Music | Electro & House. CLUB MUSIC MIXES Free Download: ▸Follow us on Instagram for Models: https://www. TO CHANNEL!!! SEGUIMI ANCHE SU FACEBOOK More Free Music: Facebook: Create your own Electro House - EDM. It's been an eventful year in dance music, to say the least. Kudos to French house wunderkind Wilfred Giroux for being the tough-love friend. CLUB & DANCE songs New House Music Mix [Club Party Lover's] Maximal Electro House Stream New Best Dance Music Electro & House Dance Club Mix By Gerrard #1 by Anthony Gerrard from desktop or your mobile device. Listen to the best Electro house dance club music track remix mix shows. Romyyca89 @ Night Party Mix _Vol.1_-_(Dance-Club Edition). Free with Apple Music subscription. Just Dance - 50 EDM Club Electro House Hits. Various Artists Roar (Glee Free Dance Edit). Electro House Special Dance Mix Electro House Progressive usa, axwell, hits , great club, bass, collection, love house music. Vários/House - Best of Dance (2CD). Compre as novidades de música na House music is a genre of electronic music created by club DJs and music producers in House music developed in Chicago's underground dance club culture in the early s, as DJs (re-issue of a November article). -

Streetdance and Hip Hop - Let's Get It Right!

STREETDANCE AND HIP HOP - LET'S GET IT RIGHT! Article by David Croft, Freelance Dance Artist OK - so I decided to write this article after many years studying various styles of Street dance and Hip Hop, also teaching these styles in Schools, Dance schools and in the community. Throughout my years of training and teaching, I have found a lack of understanding, knowledge and, in some cases, will, to really search out the skills, foundation and blueprint of these dances. The words "Street Dance" and "Hip Hop" are widely and loosely used without a real understanding of what they mean. Street Dance is an umbrella term for various styles including Bboying or breakin (breakin is an original Hip Hop dance along with Rockin and Party dance – the word break dance did not exist in the beginning, this was a term used by the media, originally it was Bboying. (Bboy, standing for Break boy, Beat boy or Bronx boy)…….for more click here Conquestcrew Popping/Boogaloo Style was created by Sam Soloman and Popping technique involves contracting your muscles to the music using your legs, arms, chest and neck. Boogaloo has a very funky groove constantly using head and shoulders. It also involves rolling the hips and knees. Locking was created by Don Campbell. This involves movements like wrist twirls, points, giving himself “5”, locks (which are sharp stops), knee drops and half splits. (Popping/Boogaloo and Locking are part of the West Coast Funk movement ). House Dance and Hip Hop. With Hip Hop coming out of the East Coast (New York) and West Coast Funk from the west (California) there was a great collaboration in cultures bringing the two coasts together. -

Dance As Protocol: Social Choreography in Elite Washington

Miskell 1 DANCE AS PROTOCOL: SOCIAL CHOREOGRAPHY IN ELITE WASHINGTON, 1920-1940 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES AND UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY HONORS IN HISTORY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY FALL 2010 AND SPRING 2011 BRIDGET MISKELL Miskell 2 In the early twentieth century social dance played an important role in communal activity. In the aftermath of World War I and as the United States struggled through the Great Depression, both the elites and the working class moved away from established practices. Americans had a new fascination with dance during the Progressive area as people contested issues of identity through bodily discourse and this interest carried into the 1920s.1 Dance halls, which had long been a place for the working-class and ethnic communities to gather, drew the interest of elite society who wanted to explore “socially marginalized urban neighborhoods and the diverse populations that inhabited them.”2 This exploration manifested itself in the nightlife. Known as “slumming”, the upper class flocked to the jazz cabarets, speakeasies and nightclubs, spurring “the development of an array of new commercialized leisure spaces that simultaneously promoted social mixing and recast the sexual and racial landscape of American urban culture and space.”3 Beginning in New York City, this trend spread to almost every major City in the United States.4 The practice, which could be traced to a century earlier, contained very different motives in the 1920s. While in the mid-nineteenth century men explored lower class areas to feed their curiosity and women remained at home, in the early twentieth century men and women together chose to interact with the socially marginalized to escape the demands of high society and break free from family constraints.5 Upper class whites reevaluated the roles of blacks in 1 Linda J. -

B-Girl Like a B-Boy Marginalization of Women in Hip-Hop Dance a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Division of the University of H

B-GIRL LIKE A B-BOY MARGINALIZATION OF WOMEN IN HIP-HOP DANCE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT MANOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN DANCE DECEMBER 2014 By Jenny Sky Fung Thesis Committee: Kara Miller, Chairperson Gregg Lizenbery Judy Van Zile ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to give a big thanks to Jacquelyn Chappel, Desiree Seguritan, and Jill Dahlman for contributing their time and energy in helping me to edit my thesis. I’d also like to give a big mahalo to my thesis committee: Gregg Lizenbery, Judy Van Zile, and Kara Miller for all their help, support, and patience in pushing me to complete this thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………… 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 1 2. Literature Review………………………………………………………………… 6 3. Methodology……………………………………………………………………… 20 4. 4.1. Background History…………………………………………………………. 24 4.2. Tracing Female Dancers in Literature and Film……………………………... 37 4.3. Some History and Her-story About Hip-Hop Dance “Back in the Day”......... 42 4.4. Tracing Females Dancers in New York City………………………………... 49 4.5. B-Girl Like a B-Boy: What Makes Breaking Masculine and Male Dominant?....................................................................................................... 53 4.6. Generation 2000: The B-Boys, B-Girls, and Urban Street Dancers of Today………………...……………………………………………………… 59 5. Issues Women Experience…………………………………………………….… 66 5.1 The Physical Aspect of Breaking………………………………………….… 66 5.2. Women and the Cipher……………………………………………………… 73 5.3. The Token B-Girl…………………………………………………………… 80 6.1. Tackling Marginalization………………………………………………………… 86 6.2. Acknowledging Discrimination…………………………………………….. 86 6.3. Speaking Out and Establishing Presence…………………………………… 90 6.4. Working Around a Man’s World…………………………………………… 93 6.5. -

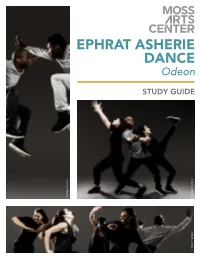

EPHRAT ASHERIE DANCE Odeon

EPHRAT ASHERIE DANCE Odeon STUDY GUIDE ©Matthew Murphy ©Matthew Murphy ©Matthew Murphy Wednesday, March 31, 2021, 10 AM EDT PROGRAM Odeon Choreographer: Ephrat Asherie, in collaboration with Ephrat Asherie Dance Music: Ernesto Nazareth Musical Direction: Ehud Asherie Lighting Design: Kathy Kaufmann Costume Design: Mark Eric We gratefully acknowledge and thank the Joyce Theater’s School & Family Programs for generously allowing the Moss Arts Center’s use and adaptation of its Ephrat Asherie Dance Odeon Resource and Reference Guide. Heather McCartney, director | Rachel Thorne Germond, associate EPHRAT ASHERIE DANCE “Ms. Asherie’s movement phrases—compact bursts of choreography with rapid-fire changes in rhythm and gestural articulation—bubble up and dissipate, quickly paving the way for something new.” –The New York Times THE COMPANY Ephrat Asherie Dance (EAD) is a dance company rooted in Black and Latinx vernacular dance. Dedicated to exploring the inherent complexities of various street and club dances, including breaking, hip-hop, house, and vogue, EAD investigates the expansive narrative qualities of these forms as a means to tell stories, develop innovative imagery, and find new modes of expression. EAD’s first evening-length work,A Single Ride, earned two Bessie nominations in 2013 for Outstanding Emerging Choreographer and Outstanding Sound Design by Marty Beller. The company has presented work at Apollo Theater, Columbia College, Dixon Place, FiraTarrega, Works & Process at the Guggenheim, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, the Joyce Theater, La MaMa, River to River Festival, New York Live Arts, Summerstage, and The Yard, among others. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Ephrat “Bounce” Asherie is a New York City-based b-girl, performer, choreographer, and director and a 2016 Bessie Award Winner for Innovative Achievement in Dance.