Wagner News No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

25–30 Juni 2018 Innehåll

Konstnärlig ledare | Roland Pöntinen 25–30 juni 2018 Innehåll 4 Välkommen! 6 Roland Pöntinen | Konstnärlig ledare 7 Andrea Tarrodi | Tonsättarporträtt 8 Ulla O’Barius | Båstad kammarmusikförening 9 Peter Wilgotsson | Musik i Syd 11 Konsertprogram VARIFRÅN KOMMER MUSIKEN? 12 Introduktion om Debussy 14 Måndag 25 juni 18 Tisdag 26 juni 23 Onsdag 27 juni 27 Torsdag 28 juni 31 Fredag 29 juni 34 Lördag 30 juni 37 Om musiken 44 Artister 70 Vinterprogram 74 BIljettinformation båstad chamber music festival 2018 3 foto anna aatola foto anna aatola et är med stor glädje och dNa. att publiken får möjlighet att möta en Välkommen sommar! förväntan jag tar över nu levande tonsättare i egen hög person ger stafettpinnen för båstad mervärde åt lyssningsupplevelsen och kan Välkommen musik! chamber music festival ge oväntade nycklar till förståelsen av inte samtidigt som jag sänder en bara vår tids musik utan även gångna tiders Välkomna underbara artister! tacksamhetens tanke till mina tonskapande. Dfantastiska föregångare helén Jahren och Karin dornbusch. deras hängivna arbete, i år heter årets tonsättare andrea tarrodi Välkommen Kära publik! tillsammans med lika hängivna volontärer, har och några händelser som ser ut som en varje år bidragit till att göra festivalen till en av tanke är att en inspelning med hennes landets viktigaste musikhändelser. stråkkvartetter framförda av »dahlkvistarna« vann en Grammis alldeles nyligen samt att Jag vill också rikta ett särskilt tack till musik i Konserthusets i stockholm traditionella syd, som stöttar och vårdar båstad chamber tonsättarweekend 2018 ägnades andrea music festival som en av blomstren i sin tarrodi och hennes musik. välkommen bukett five star festivals. -

The Wagner Society Members Who Were Lucky Enough to Get Tickets Was a Group I Met Who Had Come from Yorkshire

HARMONY No 264 Spring 2019 HARMONY 264: March 2019 CONTENTS 3 From the Chairman Michael Bousfield 4 AGM and “No Wedding for Franz Liszt” Robert Mansell 5 Cover Story: Project Salome Rachel Nicholls 9 Music Club of London Programme: Spring / Summer 2019 Marjorie Wilkins Ann Archbold 18 Music Club of London Christmas Dinner 2018 Katie Barnes 23 Visit to Merchant Taylors’ Hall Sally Ramshaw 25 Dame Gwyneth Jones’ Masterclasses at Villa Wahnfried Roger Lee 28 Sir John Tomlinson’s masterclasses with Opera Prelude Katie Barnes 30 Verdi in London: Midsummer Opera and Fulham Opera Katie Barnes 33 Mastersingers: The Road to Valhalla (1) with Sir John Tomlinson Katie Barnes 37 Mastersingers: The Road to Valhalla (2) with Dame Felicity Palmer 38 Music Club of London Contacts Cover picture: Mastersingers alumna Rachel Nicholls by David Shoukry 2 FROM THE CHAIRMAN We are delighted to present the second issue of our “online” Harmony magazine and I would like to extend a very big thank you to Roger Lee who has produced it, as well as to Ann Archbold who will be editing our Newsletter which is more specifically aimed at members who do not have a computer. The Newsletter package will include the booking forms for the concerts and visits whose details appear on pages 9 to 17. Overseas Tours These have provided a major benefit to many of our members for as long as any us can recall – and it was a source of great disappointment when we had to suspend these. Your committee have been exploring every possible option to offer an alternative and our Club Secretary, Ian Slater, has done a great deal of work in this regard. -

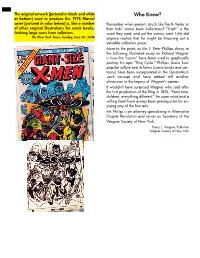

Wagner in Comix and 'Toons

- The original artwork [pictured in black and white Who Knew? at bottom] used to produce the 1975 Marvel cover [pictured in color below] is, like a number Remember when parents struck like Darth Vader at of other original illustrations for comic books, their kids’ comic book collections? “Trash” is the fetching large sums from collectors. word they used, and out the comics went. Little did The New York Times, Sunday, June 30, 2008 anyone realize that he might be throwing out a valuable collectors piece. More to the point, as Mr. F. Peter Phillips shows in the following illustrated essay on Richard Wagner is how the “comix” have been used to graphically portray his epic “Rng Cycle.” Phillips shows how popular culture and its forms (comic books and car- toons) have been incorporated in the Gesamtkust- werk concept and have added still another dimension to the legacy of Wagner’s operas. It wouldn’t have surprised Wagner who said after the first production of the Ring in 1876, “Next time, children, everything different.” An open mind and a willing heart have always been prerequisites for en- joying any of the fine arts. Mr. Phllips is an attorney specializing in Alternative Dispute Resolution and serves as Secretary of the Wagner Society of New York. Harry L. Wagner, Publisher Wagner Society of New York Wagner in Comix and ‘Toons By F. Peter Phillips Recent publications have revealed an aspect of Wagner-inspired literature that has been grossly overlooked—Wagner in graphic art (i.e., comics) and in animated cartoons. The Ring has been ren- dered into comics of substantial integrity at least three times in the past two decades, and a recent scholarly study of music used in animated cartoons has noted uses of Wagner’s music that suggest that Wagner’s influence may even more profoundly im- bued in our culture than we might have thought. -

Opera Festivals

2012 Festivals Opera JMB Travel Consultants - Opera specialists for 26 years, sharing your passion DestinationsAix-en-Provence Opera Festival ...........................4 Salzburg Opera Festival .......................................8 Bregenz Opera Festival ........................................5 Puccini Opera Festival .........................................9 Bayreuth Opera Festival .......................................5 Puccini Opera and Wine Escorted Tour ................9 Munich Opera Festival .........................................6 Verona Opera Festival........................................10 Macerata Opera Festival ......................................6 Wexford Opera Festival .....................................11 Pesaro – The Rossini Opera Festival .....................7 Wexford Opera Festival Escorted Tour ................11 Savonlinna Opera Festival ...................................7 Call to discuss your requirements with our specialists on 01242 221300 JMB Travel is one of the leading UK tour operators specialising solely in Opera, and has 26 years’ unrivalled Introductionexperience in catering to the particular needs of the Opera lover. We couple that professionalism and care of the individual’s requirements with a huge choice that covers over 10 different Music Festivals noted for their Opera, where well over 50 different productions will be performed during the season. The holidays include virtually in every case, the best grade The air holidays and flights in this brochure are ATOL protected opera ticket, -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

Tiina Rosenberg

Don ’t be Quiet TIINA ROSENBERG , Don’ ,t be Quiet ESSAYS ON FEMINISM AND PERFORMANCE Don’t Be Quiet, Start a Riot! Essays on Feminism and Performance Tiina Rosenberg Published by Stockholm University Press Stockholm University SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden www.stockholmuniversitypress.se Text © Tiina Rosenberg 2016 License CC-BY ORCID: Tiina Rosenberg: 0000-0002-7012-2543 Supporting Agency (funding): The Swedish Research Council First published 2016 Cover Illustration: Le nozze di Figaro (W.A. Mozart). Johanna Rudström (Cherubino) and Susanna Stern (Countess Almaviva), Royal Opera, Stockholm, 2015. Photographer: Mats Bäcker. Cover designed by Karl Edqvist, SUP Stockholm Studies in Culture and Aesthetics (Online) ISSN: 2002-3227 ISBN (Paperback): 978-91-7635-023-2 ISBN (PDF): 978-91-7635-020-1 ISBN (EPUB): 978-91-7635-021-8 ISBN (Kindle): 978-91-7635-022-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16993/baf This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Suggested citation: Rosenberg, Tiina 2016 Don’t Be Quiet, Start a Riot! Essays on Feminism and Performance. Stockholm: Stockholm University Press. DOI: http://dx.doi. org/10.16993/baf. License CC-BY 4.0 To read the free, open access version of this book online, visit http://dx.doi.org/10.16993/baf or scan this QR code with your mobile device. -

Tristan & Isolde

Wagner Society of New Zealand Patron: Sir Donald McIntyre NEWSLETTER Vol. 12 No. 2 September 2014 Tristan & Isolde: TRIUMPH! Mixed Emotions July 2014: two performances of Wagner one in each hemisphere and two different reactions. In Auckland the response to the APO’s concert performance brought the audience to its feet cheering. In the words of Jeanette Miller and Richard Green: “More’s the pity if it were to prove a once-in-a-lifetime concert experience—the massed standing ovation that greeted the final chord of the Auckland Philharmonia’s Tristan und Isolde was surely testament enough that New Zealand audiences have a hunger for more of the same. 12,000 miles away (give or take a few) the audience in Bayreuth was Eckehard Stier conducts while Daveda Karanas (Brangäne) keeps watch. Photo: Adrian Malloch also on its feet reacting to Frank Castorf’s ‘radically deconstructed’ Those members of the Wagner the Steersman, opened Act 1. We Ring with a different sort of hunger Society who were lucky enough to were then enthralled by Annalena in mind. Lance Ryan, who sings attend the Auckland Philharmonia’s Persson’s Isolde and Daveda Karanas the role of Siegfried in this year’s concert performance of Tristan & as Brangäne. Persson’s voice was bright production, gave the following Isolde not only became part of history, and clear while Karanas’ singing was quote to The Guardian: “I have attending the New Zealand premiere contrastingly rich and lustrous giving never come across an audience with of the work, but were treated to a the impression that she always had so much hatred, so much anger, wonderful performance. -

Sir John in Love

REAM.2122 MONO ADD RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Sir John in Love (1924-28) An Opera in Four Acts Libretto by the composer, based on Shakespeare’s (in order of appearance) Shallow, a country Justice Heddle Nash Sir Hugh Evans, a Welsh Parson Parry Jones Slender, a foolish young gentleman, Shallow’s cousin Gerald Davies Peter Simple, his servant Andrew Gold, Page, a citizen of Windsor Denis Dowling, Sir John Falstaff Roderick Jones Bardolph John Kentish Nym Sharpers attending on Falstaff Denis Catlin Pistol } Forbes Robinson Anne Page, Page’s daughter April Cantelo Mrs Page, Page’s wife Laelia Finneberg Mrs Ford, Ford’s wife Marion Lowe Sir John in Love Fenton, a young gentleman of the Court at Windsor James Johnston Dr. Caius, a French physician Francis Loring Rugby, his servant Ronald Lewis Mrs Quickly, his housekeeper Pamela Bowden The Host of the ‘Garter Inn’ Owen Brannigan Ford, a citizen of Windsor John Cameron The BBC wordmark and the BBC logo are trade marks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and are used under licence. BBC logo © BBC 1996 c © Of all the musical forms essayed by Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958), his operas have received the least recognition or respect. His propensity to write without commissions and to encourage amateur or student groups to premiere his stage pieces 3 EVANS As we sat down in Papylon 4’36” has perhaps played a part in this neglect. Yet he was incontestably a man of the theatre. 4 HOST Peace, I say! 3’04” He produced an extensive, quasi-operatic score of incidental music for Aristophanes’ , for the Cambridge Greek Play production in 1909. -

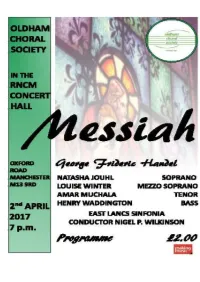

2017-04-02 Messiah

OLDHAM CHORAL SOCIETY PATRON: Jeffrey Lawton CHAIRMAN: Fred Jones Vice-Chair: Margaret Hood Vice-President: Nancy Murphy Hon. Secretary: Ray Smith Hon. Treasurer: John Price Music Director: Nigel P. Wilkinson Accompanist: Angela Lloyd-Mostyn Conductor Emeritus: John Bethell MBE Librarian: Tricia Golden / Janeane Taylor Ticket Sec.: Margaret Hallam Patrons’ Sec.: Sylvia Andrew Uniform Co-ordination: Val Dawson Webmaster: David Baird Concert Manager: Gerard Marsden Promotions Group: David Baird, Edna Gill, Margaret Hood, Fred Jones, Maggs Martin, Sue Morris, June O’Grady, Brenda Roberts, LIFE MEMBERS Eva Dale, Fred Jones, Margaret Hood, Alan Mellor, Nancy Murphy, Peter Quan, Eric Youd A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR One of the joys of being in a choir is that from time to time you get to sing your favourite work. That is my pleasure this evening. I have loved the "Messiah" for many years (not saying how many!). To my mind it is a pity that it is usually confined to the busy period of Christmas, so I am particularly pleased to have a Lenten performance. The emotion and drama of the Easter story are something quite special, and deserve to be savoured. Our wonderful soloists and the East Lancs Sinfonia will, I am sure, join with the choir to produce a magical musical experience. We will not be having our usual lighter-themed concert at Middleton Arena this year. Instead we will be holding a Choir "At Home" evening on Friday, 16th June in our regular rehearsal venue - the beautiful Ballroom of Chadderton Town Hall, from 7.30 to 10.30pm. You are invited to join us for a short concert, followed by some time for social and fund-raising activities. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 31

CONVENTION HALL . ROCHESTER Thirty-first Season, 1911-1912 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor Programme WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE MONDAY EVENING, JANUARY 29 AT 8.15 COPYRIGHT, 1911, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER : : Vladimir De Pachmann The Greatest Pianist Of the 20th Century ON TOUR IN THE UNITED STATES SEASON: 1911-1912 For generations the appearance of new stars on the musical firmament has been announced — then they came with a temporary glitter — soon to fade and to be forgotten. De Pachmann has outlived them all. With each return he won additional resplendence and to-day he is acknowl- edged by the truly artistic public to be the greatest exponent of the piano of the twentieth century. As Arthur Symons, the eminent British critic, says "Pachmann is the Verlaine or Whistler of the Pianoforte the greatest player of the piano now living." Pachmann, as before, uses the BALDWIN PIANO for the expression of his magic art, the instrument of which he himself says " .... It cries when I feel like crying, it sings joyfully when I feel like singing. It responds — like a human being — to every mood. I love the Baldwin Piano." Every lover of the highest type of piano music will, of course, go to hear Pachmann — to revel in the beauty of his music and to marvel at it. It is the beautiful tone quality, the voice which is music itself, and the wonderfully responsive action of the Baldwin Piano, by which Pachmann's miraculous hands reveal to you the thrill, the terror and the ecstasy of a beauty which you had never dreamed was hidden in sounds. -

The Genius of Valhalla: the Life of Reginald Goodall Online

5gsQm (Read free ebook) The Genius of Valhalla: The Life of Reginald Goodall Online [5gsQm.ebook] The Genius of Valhalla: The Life of Reginald Goodall Pdf Free John Lucas ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #4884408 in Books Boydell Press 2009-10-15Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.00 x .80 x 6.10l, .94 #File Name: 1843835177264 pages | File size: 79.Mb John Lucas : The Genius of Valhalla: The Life of Reginald Goodall before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Genius of Valhalla: The Life of Reginald Goodall: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Inflated Wagnerian RepBy reading manThis biography is as interesting for its account of British musical life during Goodall's lifetime as it is for the facts about him.Although he's remembered by many as a colleague and associate of Britten, as well as a conductor of Britten's music, I think it's fair to say his lasting fame is as a Wagnerian.The glowing reviews he received for his Wagner performances are quoted by Lucas, as well as miscellaneous remarks about his prowess in this music from letters and remarks.The problem is that the recorded evidence doesn't corroborate those reviews and remarks, at least not to this listener.Let's consider his "live" performances.The PARSIFAL with Jon Vickers is ludicrous. Wagner's last masterpiece in slow-motion would be an apposite description. It makes you wonder why Jon Vickers held Goodall in such high esteem.