How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parlamento Europeo

11.9.2013 IT Gazzetta ufficiale dell'Unione europea C 262 E / 1 IV (Informazioni) INFORMAZIONI PROVENIENTI DALLE ISTITUZIONI, DAGLI ORGANI E DAGLI ORGANISMI DELL'UNIONE EUROPEA PARLAMENTO EUROPEO INTERROGAZIONI SCRITTE CON RISPOSTA Interrogazioni scritte presentate dai deputati al Parlamento europeo e relative risposte date da un’Istituzione dell’Unione europea (2013/C 262 E/01) Sommario Pagina E-005730/12 by Ivo Belet to the Commission Subject: Universal chargers for digital cameras, laptops, portable media players, etc. Nederlandse versie ............................................................................................................................................................ 13 English version .................................................................................................................................................................. 14 E-005731/12 by Ivo Belet to the Commission Subject: Underground installation of high-voltage power lines Nederlandse versie ............................................................................................................................................................ 15 English version .................................................................................................................................................................. 16 E-005732/12 by Hermann Winkler to the Commission Subject: Regulation (EU) No 1131/2011 amending Annex II of Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council with regard to steviol -

Download SUR 11 In

ISSN 1806-6445 11 international journal on human rights Víctor Abramovich From Massive Violations to Structural Patterns: New Approaches and Classic Tensions in the Inter-American Human Rights System v. 6 • n. 11 • Dec. 2009 Viviana Bohórquez Monsalve and Javier Aguirre Román Biannual Tensions of Human Dignity: Conceptualization and Application to International Human Rights Law English Edition Debora Diniz, Lívia Barbosa and Wederson Rufino dos Santos Disability, Human Rights and Justice Julieta Lemaitre Ripoll Love in the Time of Cholera: LGBT Rights in Colombia ECONOmic, SOcial and CUltUral Rights Malcolm Langford Domestic Adjudication and Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: A Socio-Legal Review Ann Blyberg The Case of the Mislaid Allocation: Economic and Social Rights and Budget Work Aldo Caliari Trade, Investment, Finance and Human Rights: Assessment and Strategy Paper Patricia Feeney Business and Human Rights: The Struggle for Accountability in the UN and the Future Direction of the Advocacy Agenda InternatiOnal HUman Rights COLLOQUIUM Interview with Rindai Chipfunde-Vava, Director of the Zimbabwe Election Support Network (ZESN) Report on the IX International Human Rights Colloquium ISSN 1806-6445 SUR - INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ON HUMAN RIGHTS is SUR - HUMAN RIGHTS UNIVERSITY NETWORK is a biannual journal published in English, Portuguese and a network of academics working together with the mission Spanish by Sur - Human Rights University Network. to strengthen the voice of universities in the South on human It is available on the Internet at <http://www.surjournal.org> rights and social justice, and to create stronger cooperation between them, civil society organizations and the United SUR - International Journal on Human Rights is listed in Nations. -

NWX-NASA-JPL-AUDIO-CORE (US) Moderator: Anita Sohus 02-02-17/2:30 Pm CT Confirmation #1801281 Page 1

NWX-NASA-JPL-AUDIO-CORE (US) Moderator: Anita Sohus 02-02-17/2:30 pm CT Confirmation #1801281 Page 1 NWX-NASA-JPL-AUDIO-CORE (US) Moderator: Anita Sohus February 2, 2017 2:30 pm CT Coordinator: Thank you for standing by. Today’s call is being recorded. If you have any objections you may disconnect at this time. Thank you. You may begin. Kay Ferrari: Thank you very much. Good afternoon everyone this is Kay Ferrari from the Solar System Ambassador’s Program and NASA Nationwide. In keeping with the theme of today’s program, Women in STEM. This will be an all-female program. And I am pleased to be introducing our speaker who is going to facilitate today’s program. Jessica Kenney is an education outreach specialist at the Space Science Telescope Institute. She is the Program Director for Space Astronomy Summer Program and she will be facilitating our program. Jessica, welcome. Jessica Kenney: Thank you Kay. Thank you for your delightful introduction. It is my honor to introduce you guys to the Universe of Learning Science Briefing today entitled, Women in STEM: Hidden Figures, Modern Figures. It is a pleasure to have everyone on the call today. And because we have a full schedule we will go ahead and jump in with our first speaker, Kim NWX-NASA-JPL-AUDIO-CORE (US) Moderator: Anita Sohus 02-02-17/2:30 pm CT Confirmation #1801281 Page 2 Arcand. She is the visualization lead of NASA’s Chandra X-Ray Observatory which has its headquarters in the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts. -

Quarter II, 2016 from the President

OperantsQUARTER II, 2016 from the president f you are a practitioner, what do you do if your usual procedures aren’t working? Most of us ask others for help. The final authority, however, is not a supervisor or colleague. It is the underlying science. B. F. Skinner described Iscience as “first of all an attitude. It is a disposition to deal with the facts, rather than what one has said about them.” But what are “facts?” They are descriptions about how the world works. New discoveries may extend our understanding of phenomena. But one thing about science does not change: it does not include non-material agencies as causes of physical, biological, or behavioral events. As behavior analysts or as behaviorologists, we do not appeal to personality, selfishness, motivation, or other inferred “agencies” to explain behavior. These “agencies” do not consist of behavior. Behavior exists inside our skins of course. Like overt actions, internal behavior depends upon contingencies: the relation between existing actions, their results, and the circumstances in which those relations exist. If a procedure is not working, we do not attribute failure to an internal agency resisting change. We attribute lack of success to a set of contingencies that we need to change. Julie S. Vargas, Ph.D. President, B. F. Skinner Foundation Arabic Translated by Nidal Daou ماذا تفعل لو كنت مامرسااومامرسة يفً علم النفس او تحليل السلوك التطبيقي، و األساليب االعتيادية مل تنجح؟ يف ظروف كهذه، نلجأ لآلخرين للمساعدة. املرجع االخري فهو ليس املرشف)ة( عىل عملك او الزميل)ة(. إمنا املرجع االخري فهو العلم األسايس. -

Operants Fourth Quarter

operantsEpisode IV, 2015 from the president . F. Skinner loved to tell a story to illus- trate the power of doubling. The story has many versions. As Skinner told it, a man did a huge favor for a Chinese emperor. When the emperor asked him how he Bwould like to be paid, the man bowed and said, “Oh, just pay me in rice grains using this chess board: Count out one grain for the first square, two grains for the next, four for the next and so on, doubling each time.” That didn’t seem like much rice, so the Emperor agreed. Skinner would chuckle as he said that doubling 64 times ended up with more rice than existed in all of China. Subscriptions to Operants nearly doubled from 2013 to 2014 and again in 2015. Operants subscribers can’t continue to double for 64 years: There are fewer than 9,223,372,036,854,775,808 people on earth. But we hope to continue the magazine’s impressive growth. The growth in quality as well as subscrip- tions can be traced to the work of the editors and correspondents. Operants now links subscribers into a worldwide behavioral community. Wheth- er a contributor or a reader, your participation furthers the Foundation’s goal of making the world a better place through behavioral science. Julie S. Vargas, Ph.D. President, B. F. Skinner Foundation Chinese Traditional Translated by Libby Cheng 斯金納 (B.F. Skinner) 喜歡講故事來說明雙倍的力量。這個故事有很多版本。由Skinner講的版本是,有一個人幫了中國皇帝一個大忙。當皇帝問 該男子想要什麼報酬, 他鞠躬, 然後說:“只要使用這個棋盤付我米粒就好了, 計算方法如下: 第一個棋盤方格付一粒米,第二個付兩粒米,第三 個付四粒米,如此類推, 每次雙倍。” 這似乎並不多米,所以皇帝同意了。斯金納(Skinner)輕笑,他說,倍增64次後的米粒還要比存在於全中國的 多。 Operants的認捐在2013至2014年差不多翻了一倍,在2015年又翻了一倍, Operants的用戶無法繼續雙增64年:因地球上的人口少於 9,223,372,036,854,775,808。但是,我們希望本雜誌的認捐繼續有顯著增長。 在質量以及訂閱的增長可以追溯到編輯和通信者的工作。 Operants現在用戶鏈接到一個世界性行為業界的社群。無論是貢獻者或讀者, 您的參與進一步加強了行為學使世界變得更美好的基金會的目標。 Dutch Translated by Maximus Peperkamp & Bart Bruins B.F. -

Electric Goes Down with Pole in M-21/Alden Nash Accident YMCA

25C The Lowell Volume 14, Issue 14 Serving Lowell Area Readers Since 1893 Wednesday, February 14, 1990 Electric goes down with pole in M-21/Alden Nash accident An epileptic seizure suffered by Daniel Barrett was the cause of his vehicle leaving the road. The electrical pole was broken in three different places. Roughly 200 homes and Zeigler Ford sign and the businesses were without elec- power pole about 10-feet tricity for I1/: hours (5-7:30 above ground before the veh- p.m.) on Thursday (Feb. 8) icle came to a rest on Alden following a one-car accident Nash. at the comer of M-21 and According to Kent County Alden Nash. Deputy Greg Parolini a wit- 0 The Kent County Sheriff ness reported that the vehicle Department s report staled accelerated as it left the road- that Daniel Joseph Barrett, way. 19, of Lowell, was eastbound Barrett incurred B-injuries on M-21 when he suffered an (visible injuries) and was epileptic seizure, causing his transported to Blodgett Hos- vehicle to cross the road and pital by Lowell Ambulance. enter a small dip in the Barrett's collision caused boulevard. Upon leaving the the electrical pole to break in Following Thursday evening's accident at M-21 and Daniel Barrett suffered B-injuries (visible injuries) in low area, the car became air- three different places. A Low- borne, striking the Harold Alden Nash, a Lowell Light and Power crew was busy Thursday's accident. Acc., cont'd., pg. 2 erecting a new electrical pole. # YMCA & City sign one year agreement Alongm • Main Street rinjsro The current will be a detriment to the pool ahead of time if something is and maintenance of the this year. -

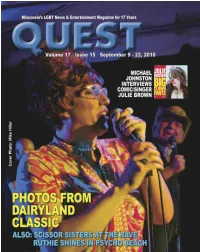

Quest Vol 17 Issue 15

Cover Photo: Mike Hiller 'RQ·W /RVH 6OHHS 2YHU ,W *HW 7HVWHG ,W·V )UHH $W QR FRVW WR \RX ZH SURYLGH U -/ ÌiÃÌ} >` ÌÀi>ÌiÌ vÀ i° U i«>ÌÌÃ E 6>VV>ÌÃ vÀ }>Þ À LÃiÝÕ> i° U i«>ÌÌÃ 6>VV>ÌÃ vÀ ÃÌÀ>} Ì i >` Üi° U ÞÕÃ À >i >ÃÃV>Ìi` 6 ÌiÃÌ} >` VÕÃi}° +RXUV 0RQGD\V 7XHVGD\V SP SP :DQQD SOD\ 'RFWRU" 1XUVH" 0D\EH 3KOHERWRPLVW" :H DUH ORRNLQJ IRU OLFHQVHG PHGLFDO VWDII YROXQWHHUV WR DGPLQLVWHU YDFFLQDWLRQV EORRG GUDZV DQG ZRUN LQ RXU 67' FOLQLF (DVW %UDG\ 6W 0LOZ FRQWDFWXV#EHVWGRUJ CREAM CITY FOUNDATION’S MARIA GREEN BAY CITY EMPLOYEE WANTS CADENAS TO RECEIVE YOUNG ALUMNI GAY PARTNER HEALTH BENEFITS AWARD FROM BELOIT COLLEGE Green Bay - A city employee for Green Bay Wisconsin has requested Milwaukee - Maria Cadenas, Executive Director of Cream City Founda - health insurance benefits for his domestic partner reported the Green tion, is being honored by Beloit College with the Young Alumni Award. Bay Press Gazette. If approved by the Green Bay City Council, this The sixth person to receive this award, Cadenas was chosen by Beloit would most likely require a policy change making Green Bay the first College’s Alumni Association Board of Directors and will be presented municipality in Northeastern Wisconsin to provide those benefits for the award during her 10th year Homecoming/Reunion weekend in late same sex partners. Presently De Pere’s school district is the only other September. non-private employer to offer these benefits. The Young Alumni Award is given to young Beloit College alumni on David Fowles, a long-time employee who drives a truck for the city's the basis of overall achievements, personal growth in career, and out - Public Works Department had previoulsy registered with his partner as standing civic, cultural, and professional / business service in such ways a couple in the states domsetic partner registry. -

Gay Gamesiii, P

JOSEPH E. SEAGRAM & SONS, INC. supports the AIDS service organizations that provide care and treatment to people with AIDS and supports education and research for the prevention and cure of AIDS. Please join us at AID & COMFORT II September 22, 1990 Berkeley, California Champagne Perrier-Jouet The Monterey Vineyard Chivas Regal Seagra m's VO Crown Royal Seagram's 7 Crown Martell Cognac Sterling Vineyards Mumm Champagne The Glenlivet Scotch Sandeman Ports & Sherries Wyborowa Vodka NEWS 12 ARTS Boston's Marie Film Mo' Better Blues ,55 Acacia, Film Heiner Carow 56 women's discus Music Edwina l£e Tyler 58 winner at Gay GamesIII, p. 20 Books The Body and Its Dangers 62 Photo: Patsy Books A Body to I¥ For 63 Lynch/OutWeek . Books When the Pamt Boy Sing1Ibe Black Marble PooV A~~ 'M Artcetera Film Director Jennie Livingston 65 HEAlTH HEALTII Political Science (Harrington) 40 DEPARTMENTS Outspoken (Editorial) 4 Letters 5 Stonewall Riots (Natalie) 5 Blurt Out 6 Jennifer Camper 8 NO TIME FORMILLER TIME' 42 Sotomayor 10 AI Weisel on Jesse Helms, Miller beer and pre Obituaries 32 fIrst gay and lesbian boycott of the '90s Liberation Logic (fulayan) 34 The Doctor Is Out (Silverstein) 36 Look Out 48 Out of My Hands (BalD 50 Gossip Watch 51 Out on the Town (Tracey and Pammy) 52 Going Out Calendar (X) 70 On the Cover: Illustration by Steven Stines Tuning In (X) 72 Dancing Out (X) 73 Community Directory 74 Bar Guide 76 OutWeek jlSSN 1047-8442) is published weekly (52, issues) manner, either in whole or in part, without written permiuion by OutWeek Publishing Corporation, 159 W. -

Youth Perceptions of Mtv Reality

WHEN IS REALITY REAL?: YOUTH PERCEPTIONS OF MTV REALITY PROGRAMS A thesis presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Rachel M. Potratz November 2007 2 This thesis titled WHEN IS REALITY REAL?: YOUTH PERCEPTIONS OF MTV REALITY PROGRAMS by RACHEL M. POTRATZ has been approved for the School of Telecommunications and the Scripps College of Communication by Norma Pecora Professor, School of Telecommunications Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication 3 Abstract POTRATZ, RACHEL M., M.A., November 2007, School of Telecommunications WHEN IS REALITY REAL?: YOUTH PERCEPTIONS OF MTV REALITY PROGRAMS (125 p). Director of Thesis: Norma Pecora This thesis examines how college freshmen relate to the personalities and content on MTV reality programs. Drawing from current theories about how viewers relate to television such as realism perceptions, identification, wishful identification, and parasocial interaction, this project looks takes a qualitative approach to understanding the particular relationships that exist between young viewers and the content and young casts of MTV reality programs. Eight college freshmen at a Midwestern university were interviewed about their perceptions of MTV reality programs, particularly Real World, Laguna Beach and The Hills. Additionally, a survey of 78 students was conducted in an introductory telecommunications course. It was found that judgments about the realism were based primarily on the students’ use of comparisons with their own lives and experiences. Additionally, knowledge of production processes played a role in realism perceptions. It was also found that students engaged in parasocial interaction and used reality television to learn about the world. -

UD Police Seize Drugs in Dormitory Authorities Search for Missing Suspect by Lisa Greiner Were Selling the Drugs

...... ---------------~.---,; _. ---·-\\' ,,----------- Fishers cast off _,.,_ .. ,/ ' .... ,~ Women's lacrosse Speci(l .l~rteport: Latin .America into trout season ..... - ...... ~ a e 4 . sticks UMBC ___.-::::::::;:::::;--""~ 11 \~?~~ FREE TUESDAY .Delaware vs. Delaware State: the sports rivalry that never was By jeff Pearlman college. lo yaltit~s of sports fans within the state. "Most players want to see it happen, but would bring Delaware closer together," he Staff Reporter The University of Delaware Fightin' Others believe the university will not play the coaches don't think that they could give said. It forms an exciting picture in the minds Blue Hens again st the Delaware State Delaware State because officials and us a game," Brantley said. of most Delaware sports fans. College Hornets. coaches don 't see the advantage of a playing Bill Collick, Delaware State football Close, but not dose enough Football coach Harold R. "Tubby" a smaller school, or because they fear coach, said, "I think it would be The two teams came close to playing in Raymond coaching against former player See Column Page 6 losing 1.0 Delaware State's powerful teams. 1remendous, only in the sense that it would the late 1970s, but the rivalry never Bill Collick or renowned slam-dunkcr Alex Iron ically, Delaware and Delaware State "There seems 1.0 be feeling from some of be a great thing for Delaware." materialized. Coles going against one of the nation's have never met in any high-revenue sports our coaches that we're above them, and that "Many kids who played against each "Back in 1979 the two schools reached · · leading scorers, Tommy Davis. -

Xavier Names New Rector RHA President Resigns at Last Week's

SanF FranciscoO GHORN UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO VOLUME 89, NUMBER 17 THURSDAY, MARCH 11,1993 RHA President resigns at last week's Senate meeting Foghorn Staff Report didn't know that she couldn't sit on the Senate as a non-student and he blamed Residence Hall Association President the "misunderstanding" on "Constitu Rebecca Cardinal resigned from her post tional overlap" which he hopes will be on the ASUSF Senate after the March 2 cleared up in Constitutional revisions. ASUSF Senate meeting. The ASUSF Constitution states that in The Foghorn has learned that Cardi order to be a member of ASUSF, stu nal is not, and has not ever been, a dents must be "any undergraduate stu student at USF. dent registered and enrolled in the Col Cardinal, a student at the Academy of lege of Arts and Sciences, McLaren Art, has only been living at USF, there School of Business, and the School of fore she is able to retain her position as Nursing in compliance with the rules and RHA President. She is not a Co-op stu policies of the University of San Fran dent, as believed, a status needed in cisco" and they must "pay the mandatory order to sit on the Senate. Associated Student fee(s)." According to Gandhi Soundararajan, As a non-student, Cardinal has never ASUSF President, he was told about paid the mandatory ASUSF fee. Cardinal's status one week ago by Bill Cardinal, just like all ASUSF Sena Clark, Senate advisor and director of tors, took an oath of office last May Student Leadership and Outreach Ser swearing to "uphold and defend the Con vices. -

October 7, 2019 Strategy Session Minutes Book 148, Page 827

October 7, 2019 Strategy Session Minutes Book 148, Page 827 The City Council of the City of Charlotte, North Carolina convened for a Strategy Session on Monday, October 7, 2019 at 5:46 p.m. in Room 267 of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Government Center with Mayor Vi Lyles presiding. Councilmembers present were Dimple Ajmera, Tariq Bokhari, Ed Driggs, Larken Egleston, Julie Eiselt, Matt Newton, Greg Phipps and Braxton Winston II. ABSENT: Councilmembers Justin Harlow, LaWana Mayfield, and James Mitchell. * * * * * * * AGENDA OVERVIEW Marcus Jones, City Manager said I want to start off by highlighting that the great part about our Strategy Sessions is that there is an opportunity for items that have been in Committee, that have been voted out of Committee to come before the full body during the Strategy Session. We have two items tonight that have come out of Committee, one being the Business Investment Grant Policy and the other being the Street Maps. When we get to Councilmember Phipps’ Committee, there is one item that deals with policies around our Municipal Service Districts that while we don’t have a presentation for it, he will address it during that time. Those are the issues that are coming out of Council Committees; we also have an update on Vision Zero as well as the Waste Water Master Plan and one of the things that we do at the Strategy Session also is to give you a heads up before something comes on a future agenda. So, you will have an item on a future agenda around the Waste Water Master Plan and then lastly before the Committee Updates; at the last Business Meeting, there was a question about the Neighbors App by Ring, and we have Deputy Police Chief Estes here tonight to help address that.