Public Ritual and the Proclamation of Richard Cromwell As Lord

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholicism HDT WHAT? INDEX

ST. BERNARD’S PARISH OF CONCORD “I know histhry isn’t thrue, Hinnissy, because it ain’t like what I see ivry day in Halsted Street. If any wan comes along with a histhry iv Greece or Rome that’ll show me th’ people fightin’, gettin’ dhrunk, makin’ love, gettin’ married, owin’ th’ grocery man an’ bein’ without hard coal, I’ll believe they was a Greece or Rome, but not befur.” — Dunne, Finley Peter, OBSERVATIONS BY MR. DOOLEY, New York, 1902 “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Roman Catholicism HDT WHAT? INDEX ROMAN CATHOLICISM CATHOLICISM 312 CE October 28: Our favorite pushy people, the Romans, met at Augusta Taurinorum in northern Italy some even pushier people, to wit the legions of Constantine the Great — and the outcome of this would be an entirely new Pax Romana. While about to do battle against the legions of Maxentius which outnumbered his own 4 to 1, Constantine had a vision in which he saw a compound symbol (chi and rho , the beginning of ) appearing in the cloudy heavens,1 and heard “Under this sign you will be victorious.” He placed the symbol on his helmet and on the shields of his soldiers, and Maxentius’s horse threw him into the water at Milvan (Mulvian) Bridge and the Roman commander was drowned (what more could one ask God for?). 1. In a timeframe in which no real distinction was being made between astrology and astronomy, you will note, seeing a sign like this in the heavens may be classed as astronomy quite as readily as it may be classed as astrology. -

Being a Thesis Submitted for the Degree Of

The tJni'ers1ty of Sheffield Depaz'tient of Uistory YORKSRIRB POLITICS, 1658 - 1688 being a ThesIs submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by CIthJUL IARGARRT KKI August, 1990 For my parents N One of my greater refreshments is to reflect our friendship. "* * Sir Henry Goodricke to Sir Sohn Reresby, n.d., Kxbr. 1/99. COff TENTS Ackn owl edgements I Summary ii Abbreviations iii p Introduction 1 Chapter One : Richard Cromwell, Breakdown and the 21 Restoration of Monarchy: September 1658 - May 1660 Chapter Two : Towards Settlement: 1660 - 1667 63 Chapter Three Loyalty and Opposition: 1668 - 1678 119 Chapter Four : Crisis and Re-adjustment: 1679 - 1685 191 Chapter Five : James II and Breakdown: 1685 - 1688 301 Conclusion 382 Appendix: Yorkshire )fembers of the Coir,ons 393 1679-1681 lotes 396 Bibliography 469 -i- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Research for this thesis was supported by a grant from the Department of Education and Science. I am grateful to the University of Sheffield, particularly the History Department, for the use of their facilities during my time as a post-graduate student there. Professor Anthony Fletcher has been constantly encouraging and supportive, as well as a great friend, since I began the research under his supervision. I am indebted to him for continuing to supervise my work even after he left Sheffield to take a Chair at Durham University. Following Anthony's departure from Sheffield, Professor Patrick Collinson and Dr Mark Greengrass kindly became my surrogate supervisors. Members of Sheffield History Department's Early Modern Seminar Group were a source of encouragement in the early days of my research. -

HISTORY MEDIUM TERM PLAN (MTP) YEAR 4 2020: Taught 1St Half of Each Term HISTORY MTP Y4 Autumn 1: 8 WEEKS Spring 1: 6 WEEKS Su

HISTORY MEDIUM TERM PLAN (MTP) YEAR 4 2020: Taught 1st half of each term HISTORY Autumn 1: 8 WEEKS Spring 1: 6 WEEKS Summer 1: 6 WEEKS MTP Y4 Topic Title: Anglo-Saxons / Scots Topic Title: Vikings Topic Title: UK Parliament Taken from the Year Key knowledge: Key knowledge: Key knowledge: group • Roman withdrawal from Britain in CE • Viking raids and the resistance of Alfred the Great and • Establishment of the parliament - division of the curriculum 410 and the fall of the western Roman Athelstan. Houses of Lords and Commons. map Empire. • Edward the Confessor and his death in 1066 - prelude to • Scots invasions from Ireland to north the Battle of Hastings. Key Skills: Britain (now Scotland). • Anglo-Saxons invasions, settlements and Key Skills: kingdoms; place names and village life • Choose reliable sources of information to find out culture and Christianity (eg. Canterbury, about the past. Iona, and Lindisfarne) • Choose reliable sources of information to find out about • Give own reasons why changes may have occurred, the past. backed up by evidence. • Give own reasons why changes may have occurred, • Describe similarities and differences between people, Key Skills: backed up by evidence. events and artefacts. • Describe similarities and differences between people, • Describe how historical events affect/influence life • Choose reliable sources of information events and artefacts. today. to find out about the past. • Describe how historical events affect/influence life today. Chronological understanding • Give own reasons why changes may Chronological understanding • Understand that a timeline can be divided into BCE have occurred, backed up by evidence. • Understand that a timeline can be divided into BCE and and CE. -

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and Democracy in Britain C1000-2014

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and democracy in Britain c1000-2014. 1. Describe the Anglo-Saxon system of government. [4] • Witan –The relatives of the King, the important nobles (Earls) and churchmen (Bishops) made up the Kings council which was known as the WITAN. These men led the armies and ruled the shires on behalf of the king. In return, they received wealth, status and land. • At local level the lesser nobles (THEGNS) carried out the roles of bailiffs and estate management. Each shire was divided into HUNDREDS. These districts had their own law courts and army. • The Church handled many administrative roles for the King because many churchmen could read and write. The Church taught the ordinary people about why they should support the king and influence his reputation. They also wrote down the history of the period. 2. Explain why the Church was important in Anglo-Saxon England. [8] • The church was flourishing in Aethelred’s time (c.1000). Kings and noblemen gave the church gifts of land and money. The great MINSTERS were in Rochester, York, London, Canterbury and Winchester. These Churches were built with donations by the King. • Nobles provided money for churches to be built on their land as a great show of status and power. This reminded the local population of who was in charge. It hosted community events as well as religious services, and new laws or taxes would be announced there. Building a church was the first step in building a community in the area. • As churchmen were literate some of the great works of learning, art and culture. -

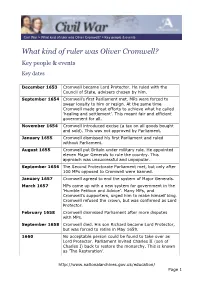

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Cromwelliana 2012

CROMWELLIANA 2012 Series III No 1 Editor: Dr Maxine Forshaw CONTENTS Editor’s Note 2 Cromwell Day 2011: Oliver Cromwell – A Scottish Perspective 3 By Dr Laura A M Stewart Farmer Oliver? The Cultivation of Cromwell’s Image During 18 the Protectorate By Dr Patrick Little Oliver Cromwell and the Underground Opposition to Bishop 32 Wren of Ely By Dr Andrew Barclay From Civilian to Soldier: Recalling Cromwell in Cambridge, 44 1642 By Dr Sue L Sadler ‘Dear Robin’: The Correspondence of Oliver Cromwell and 61 Robert Hammond By Dr Miranda Malins Mrs S C Lomas: Cromwellian Editor 79 By Dr David L Smith Cromwellian Britain XXIV : Frome, Somerset 95 By Jane A Mills Book Reviews 104 By Dr Patrick Little and Prof Ivan Roots Bibliography of Books 110 By Dr Patrick Little Bibliography of Journals 111 By Prof Peter Gaunt ISBN 0-905729-24-2 EDITOR’S NOTE 2011 was the 360th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester and was marked by Laura Stewart’s address to the Association on Cromwell Day with her paper on ‘Oliver Cromwell: a Scottish Perspective’. ‘Risen from Obscurity – Cromwell’s Early Life’ was the subject of the study day in Huntingdon in October 2011 and three papers connected with the day are included here. Reflecting this subject, the cover illustration is the picture ‘Cromwell on his Farm’ by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), painted in 1874, and reproduced here courtesy of National Museums Liverpool. The painting can be found in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village, Wirral, Cheshire. In this edition of Cromwelliana, it should be noted that the bibliography of journal articles covers the period spring 2009 to spring 2012, addressing gaps in the past couple of years. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Governor John Blackwell: His Life in England and Ireland OHN BLACKWELL is best known to American readers as an early governor of Pennsylvania, the most recent account of his J governorship having been published in this Magazine in 1950. Little, however, has been written about his services to the Common- wealth government, first as one of Oliver Cromwell's trusted cavalry officers and, subsequently, as his Treasurer at War, a position of considerable importance and responsibility.1 John Blackwell was born in 1624,2 the eldest son of John Black- well, Sr., who exercised considerable influence on his son's upbringing and activities. John Blackwell, Sr., Grocer to King Charles I, was a wealthy London merchant who lived in the City and had a country house at Mortlake, on the outskirts of London.3 In 1640, when the 1 Nicholas B. Wainwright, "Governor John Blackwell," The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (PMHB), LXXIV (1950), 457-472.I am indebted to Professor Wallace Notestein for advice and suggestions. 2 John Blackwell, Jr., was born Mar. 8, 1624. Miscellanea Heraldica et Genealogica, New Series, I (London, 1874), 177. 3 John Blackwell, Sr., was born at Watford, Herts., Aug. 25, 1594. He married his first wife Juliana (Gillian) in 1621; she died in 1640, and was buried at St. Thomas the Apostle, London, having borne him ten children. On Mar. 9, 1642, he married Martha Smithsby, by whom he had eight children. Ibid.y 177-178. For Blackwell arms, see J. Foster, ed., Grantees 121 122, W. -

OLIVER CROMWELL: CHANGE and CONTINUITY a Master's Thesis Presented to the School of Graduate Studies Department Ofhistory Indian

OLIVER CROMWELL: CHANGE AND CONTINUITY A Master's Thesis Presented to The School of Graduate Studies Department ofHistory Indiana State University Terre Haute, Indiana In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree by Kari L. Ellis May2002 INDIANA STATE UM!VERSITY UBRARY ll APPROVAL SHEET The thesis ofKari L. Ellis, Contribution to the School of Graduate Studies, Indiana State University, Series I, Number 2166, under the title Oliver Cromwell: Change and Continuity is approved as partial fulfillment of the Master of Arts Degree in the amount of six semester hours of graduate credit. Committee Chairperson r 111 ABSTRACT This study looks at the life of Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector ofEngland, in an effort to clarify the diverse and conflicting interpretations resulting from a lack of agreement between those who are biased for and against the Lord Protector. The purpose of the study of this conflicting information is not to settle whether Cromwell was a good figure or bad, but to define more clearly his time. Cromwell, clarified, creates a broader understanding of the seventeenth century Englishman. An introduction develops a brief summarization of Pre-Reformation Europe, the forces which brought changes, Reformation Europe and the Post-Reformation era in which Cromwell lived. The non-Cromwellian periods were included to develop a broader picture for the reader of the atmosphere into which Cromwell emerged. The study concentrates on six key points of conflict within the lifetime of Cromwell and discussion ofthose conflicts through use of periods or roles within his life. Cromwell's changeable nature does not lend itselfto a static, one-dimensional interpretation, but rather to one that attempts to incorporate the normal fluctuations of human nature and the continuity of change. -

Download (1287Kb)

Manuscript version: Author’s Accepted Manuscript The version presented in WRAP is the author’s accepted manuscript and may differ from the published version or Version of Record. Persistent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/123427 How to cite: Please refer to published version for the most recent bibliographic citation information. If a published version is known of, the repository item page linked to above, will contain details on accessing it. Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: Please refer to the repository item page, publisher’s statement section, for further information. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected]. warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications 1 Cover page: Professor Bernard Capp Dept of History University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7AL Email: [email protected] 02476523410 2 Healing the Nation: Royalist Visionaries, Cromwell, and the Restoration of Charles II Bernard Capp Abstract The radical visionaries of the civil war era had several royalist counterparts, today often overlooked. -

History Term 4

History: Why were Kings back in Fashion by 1660? Year 7 Term 4 Timeline Key Terms Key Questions 1625 Charles I becomes King of England. Civil War A war between people of the same country. What Caused the English Civil War? The Divine Right of Kings — Charles I felt that God had given him Charles closes Parliament. The Eleven Years of This is a belief that the King or Queen is the most 1629 Divine Right of the power to rule and so Parliament should follow his leadership. Tyranny begin. powerful person on earth as God put them into Kings Parliament disagreed with the King over the Divine Right of Kings. power. Parliament believed it should have an important role in running the Charles reopens Parliament in order to raise 1640 country. money for war. Parliament tried to limit the King’s power. Charles responded by Eleven Years Charles I ruled England without Parliament for declaring war on Parliament in 1642. Tyranny eleven years. Charles I attempts to arrest 5 members of 1642 parliament. The English Civil War begins. Why did Parliament Win the War? A government where a King or Queen is the Head of Monarchy 1644 Parliamentarians win the Battle of Marston Moor. State. The New Model Army was created by Parliamentarians in 1645. These soldiers were paid for their services and trained well. 1645 Parliamentarians win the Battle of Naseby. A group in the UK elected by the people. They have Parliament had more money. They controlled the south of England Parliament which was much richer in resources. -

Vol. VIII. No. 4. Ice Per Number 2,- (50 Cents.); for the Year, Payable in Advance, 5/- ($1.25)

Vol. VIII. No. 4. ice per number 2,- (50 cents.); for the year, payable in advance, 5/- ($1.25). THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS' HISTORICAL SOCIETY. TENTH MONTH (OCTOBER), 1911. London: HEADLEY BROTHERS, 140, BISHOPSGATE, E.G. Philadelphia: HERMAN NEWMAN, 1010 ARCH New York: DAVID S. TABER, 144 EAST 20TH STREET. VOLUME J, 1903-1904 CONTAINS : 'he Handwriting of George Fox. Illustrated. Our Recording Clerks : (i.) Ellis Hookes. (2.) Richard Richardson. The Case of William Gibson, 1723. Illustrated. The Quaker Family of Owen. Cotemporary Account of Illness and Death of George Fox. Early Records of Friends in the South of Scotland. Edmund Peckover's Travels in North America. VOLUME 2, 1905. CONTAINS : Deborah Logan and her Contributions to History. Joseph Williams's Recollections of the Irish Rebellion. William Penn's Introduction of Thomas Ellwood. Meetings in Yorkshire, 1668. Letters in Cypher from Francis Howgill to George Fox. The Settlement of London Yearly Meeting. oseph Rule, the Quaker in White. Edmund Peckover, Ex-Soldier and Quaker. Illustrated. u William Miller at the King's Gardens." VOLUME 3, 1906, CONTAINS ! Words of Sympathy for New England Sufferers. David Lloyd. Illustrated. King's Briefs, the Forerunners of Mutual Insurance Societies. Memoirs of the Life of Barbara Hoyland. u Esquire Marsh." Irish Quaker Records. VOLUME 4, 1907. CONTAINS : Our Bibliographers John Whiting. Presentations in Episcopal Visitations, 1662-1679. Episodes in the Life of May Drummond. The Quaker Allusions in u The Diary of Samuel Pepys." Illustrated. Personal Recollections of American Ministers, 1828-1852. Early Meetings in Nottinghamshire. Vol. VIII. No. 4. Tenth Month (October), 1911.