Radiohead and Identity: a Moon Shaped Pool and the Process of Identity Construction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

LCO Jonny Greenwood Feb FINAL HB

For immediate release Jonny Greenwood and the London Contemporary Orchestra Soloists in concert Sunday 23 February 2014 Wapping Hydraulic Power Station, E1W PerFormance at 7:30pm Tickets: £28 (incl. booking fee) www.lcorchestra.co.uk Guitarist and acclaimed composer Jonny Greenwood is once again joining forces with the London Contemporary Orchestra (LCO) to present a special one-off performance featuring music from his catalogue of film scores as well as a showcase of new material by Greenwood, at the Wapping Hydraulic Power Station in East London, Sunday 23 February 2014. Greenwood will appear alongside the LCO Soloists playing guitar, electronics and the Ondes Martenot. In addition to music by Greenwood, which includes cues from his scores for the Oscar and BAFTA-nominated films There Will Be Blood and The Master, and Japanese film Norwegian Wood based on the book by Haruki Murakami, the concert features works by J.S. Bach, Henry Purcell and contemporary British composer Edmund Finnis. This performance will mark a continued creative relationship between the London Contemporary Orchestra and Jonny Greenwood. The LCO has been performing Greenwood’s orchestral works since 2008 and this concert, curated by Greenwood and the LCO’s Artistic Directors Hugh Brunt and Robert Ames, will be the second major collaboration between the composer and orchestra since the LCO performed and recorded the score for the lauded 2012 film The Master, directed by Paul Thomas Anderson and starring Philip Seymour Hoffman and Joaquin Phoenix. Since 2003 Greenwood has become well known for his work as a film composer, and has scored five major films, including Bodysong, There Will Be Blood, We Need To Talk About Kevin, Norwegian Wood and The Master. -

The BG News December 12, 2003

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 12-12-2003 The BG News December 12, 2003 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News December 12, 2003" (2003). BG News (Student Newspaper). 7211. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/7211 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Bowling Green State University FRIDAY December 12, 2003 HOCKEY: BG hockey takes on PARTLY CLOUDY Findlay, looking to break HIGH: 31 I LOW: 18 their winless streak www.hgnews.com A daily independent student press VOLUME 98 ISSUE 71 before holiday; PAGE 5 NEWS Third Ohio 'Pif open on Wooster By Monica Frost then choose between a selection a.m. to 3 a.m. Thursday through University. "It's a healthy alter- . REPORICO of fresh meat or vegetarian Saturday from 11 a.m. to 4 a.m. native to fast food," Paglio said. Watch out local sandwich options. Customers can also and Sunday from noon until 3 "Everything is so fresh - I just shops — there's a new kid on the customize their pita selection a.m. love them." block. with cheeses, vegetable top- Stein said he believes The Pita The Pita Pit has 11 pitas under ". -

Radiohead's Pre-Release Strategy for in Rainbows

Making Money by Giving It for Free: Radiohead’s Pre-Release Strategy for In Rainbows Faculty Research Working Paper Series Marc Bourreau Telecom ParisTech and CREST Pinar Dogan Harvard Kennedy School Sounman Hong Yonsei University July 2014 RWP14-032 Visit the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series at: http://web.hks.harvard.edu/publications The views expressed in the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. Faculty Research Working Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. www.hks.harvard.edu Makingmoneybygivingitforfree: Radiohead’s pre-release strategy for In Rainbows∗ Marc Bourreau†,Pınar Dogan˘ ‡, and Sounman Hong§ June 2014 Abstract In 2007 a prominent British alternative-rock band, Radiohead, pre-released its album In Rainbows online, and asked their fans to "pick-their-own-price" (PYOP) for the digital down- load. The offer was available for three months, after which the band released and commercialized the album, both digitally and in CD. In this paper, we use weekly music sales data in the US between 2004-2012 to examine the effect of Radiohead’s unorthodox strategy on the band’s al- bum sales. We find that Radiohead’s PYOP offer had no effect on the subsequent CD sales. Interestingly, it yielded higher digital album sales compared to a traditional release. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #Bamnextwave

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Place BAM Harvey Theater Oct 11—13 at 7:30pm; Oct 13 at 2pm Running time: approx. one hour 15 minutes, no intermission Created by Ted Hearne, Patricia McGregor, and Saul Williams Music by Ted Hearne Libretto by Saul Williams and Ted Hearne Directed by Patricia McGregor Conducted by Ted Hearne Scenic design by Tim Brown and Sanford Biggers Video design by Tim Brown Lighting design by Pablo Santiago Costume design by Rachel Myers and E.B. Brooks Sound design by Jody Elff Assistant director Jennifer Newman Co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects and LA Phil Season Sponsor: Leadership support for music programs at BAM provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund Major support for Place provided by Agnes Gund Place FEATURING Steven Bradshaw Sophia Byrd Josephine Lee Isaiah Robinson Sol Ruiz Ayanna Woods INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE Rachel Drehmann French Horn Diana Wade Viola Jacob Garchik Trombone Nathan Schram Viola Matt Wright Trombone Erin Wight Viola Clara Warnaar Percussion Ashley Bathgate Cello Ron Wiltrout Drum Set Melody Giron Cello Taylor Levine Electric Guitar John Popham Cello Braylon Lacy Electric Bass Eileen Mack Bass Clarinet/Clarinet RC Williams Keyboard Christa Van Alstine Bass Clarinet/Contrabass Philip White Electronics Clarinet James Johnston Rehearsal pianist Gareth Flowers Trumpet ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Carolina Ortiz Herrera Lighting Associate Lindsey Turteltaub Stage Manager Shayna Penn Assistant Stage Manager Co-commissioned by the Los Angeles Phil, Beth Morrison Projects, Barbican Centre, Lynn Loacker and Elizabeth & Justus Schlichting with additional commissioning support from Sue Bienkowski, Nancy & Barry Sanders, and the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. -

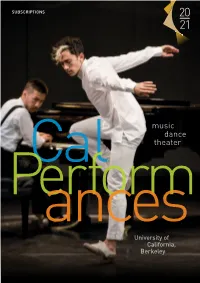

2020-21-Brochure.Pdf

SUBSCRIPTIONS 20 21 music dance Ca l theater Performances University of California, Berkeley Letter from the Director Universities. They exist to foster a commitment to knowledge in its myriad facets. To pursue that knowledge and extend its boundaries. To organize, teach, and disseminate it throughout the wider community. At Cal Performances, we’re proud of our place at the heart of one of the world’s finest public universities. Each season, we strive to honor the same spirit of curiosity that fuels the work of this remarkable center of learning—of its teachers, researchers, and students. That’s why I’m happy to present the details of our 2020/21 Season, an endlessly diverse collection of performances rivaling any program, on any stage, on the planet. Here you’ll find legendary artists and companies like cellist Yo-Yo Ma, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra with conductor Gustavo Dudamel, the Mark Morris Dance Group, pianist Mitsuko Uchida, and singer/songwriter Angélique Kidjo. And you’ll discover a wide range of performers you might not yet know you can’t live without—extraordinary, less-familiar talent just now emerging on the international scene. This season, we are especially proud to introduce our new Illuminations series, which aims to harness the power of the arts to address the pressing issues of our time and amplify them by shining a light on developments taking place elsewhere on the Berkeley campus. Through the themes of Music and the Mind and Fact or Fiction (please see the following pages for details), we’ll examine current groundbreaking work in the university’s classrooms and laboratories. -

Exposing Corruption in Progressive Rock: a Semiotic Analysis of Gentle Giant’S the Power and the Glory

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY Robert Jacob Sivy University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.459 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sivy, Robert Jacob, "EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 149. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/149 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Download Zip Albums Freeorrent Marques Houston, MH ##TOP## Full Album Zip

download zip albums freeorrent Marques Houston, MH ##TOP## Full Album Zip. marques houston, marques houston wife, marques houston net worth, marques houston age, marques houston wife age, marques houston songs, marques houston movies, marques houston and omarion, marques houston brother, marques houston height, marques houston group. DOWNLOAD. Действия. Singer, songwriter, and actor who started out in Immature/IMx but later topped the R&B charts with his solo work. Read Full Biography. Artist Information . Jump to Studio albums — Mr. Houston. Released: September 29, 2009; Label: MusicWorks, Fontana; Formats: CD, digital download. 62, 12. Mattress Music.. Marques Houston, MH Full Album Zip. Listen to Marques Houston in full in the Spotify app.Naked (Explicit Version) By Marques Houston.. 7 Th ng 4 Download Marques Houston Mh Album Free. marques houston mh . houston veteran zip, marques houston mattress music album download zip. Download Full Album, Download Marques Houston - . Marques Houston - Mattress Music Free Torrent, . veteran.zip mediafire 41.28 mb . Free download Marques Houston Mp3. We have about 30 mp3 files ready to play and download. To start this . Full discography of Marques Houston. Marques . Marques Houston Mr Houston Download Zip - issuu.com.. MH's BEST album, period! This is one of those timeless albums that you just have to have if your a R&B fan (specially 90's BORN). Marques Houston is Really 1 . Veteran | Marques Houston to stream in hi-fi, or to download in True CD Quality . of the songwriting and production work is greater than that of Naked and MH.. Houston, Marques : Veteran CD. $5.00 . Marques Houston : Naked (Clean Version) [us Import] CD (2005). -

The Strokes Share New Episode of Pirate Radio Series Featuring Colin Jost and Gordon Raphael

THE STROKES SHARE NEW EPISODE OF PIRATE RADIO SERIES FEATURING COLIN JOST AND GORDON RAPHAEL “BAD DECISIONS” CLIMBING TOP 10 AT ALT RADIO FIRST ALBUM IN SEVEN YEARS THE NEW ABNORMAL OUT NOW VIA CULT/RCA RECORDS TO CRITICAL ACCLAIM July 23, 2020—Today, The Strokes share a new installment of their ongoing pirate radio series, “Five Guys Talking About Things They Know Nothing About”—watch it HERE. The new episode is the third installment of the show, and the first in a series in which the band will speak with the producers of their albums. The episode airing today features The Strokes in conversation with Gordon Raphael—who produced their debut EP The Modern Age, their first two LPs Is This It and Room On Fire and contributed to their third LP First Impressions Of Earth—as well as their longtime friend, SNL’s Colin Jost. The band’s new album The New Abnormal, their first in seven years, was released in April to widespread critical acclaim. The album’s lead single, “Bad Decisions,” is currently Top 10 at Alternative radio and still climbing, marking the band’s first Alternative Top 10 since 2006 and setting the record for the most time between Alternative Top 10 entries. Additionally, “Bad Decisions,” went #1 on AAA in April. Upon release, The New Abnormal debuted at #1 on Billboard’s Top Album Sales Chart and reached #8 on the Billboard 200, #1 Current Rock Album, #1 Top Current Album, #1 Current Alternative Album and #1 Vinyl Album. Of The New Abnormal, The Times of London praises “The Strokes give us their second masterpiece,” while The -

6. the Evolving Role of Music Journalism Zachary Woolfe and Alex Ross

Classical Music Contemporary Perspectives and Challenges Classical Music This kaleidoscopic collection reflects on the multifaceted world of classical music as it advances through the twenty-first century. With insights drawn from Contemporary Perspectives and Challenges leading composers, performers, academics, journalists, and arts administrators, special focus is placed on classical music’s defining traditions, challenges and contemporary scope. Innovative in structure and approach, the volume comprises two parts. The first provides detailed analyses of issues central to classical music in the present day, including diversity, governance, the identity and perception of classical music, and the challenges facing the achievement of financial stability in non-profit arts organizations. The second part offers case studies, from Miami to Seoul, of the innovative ways in which some arts organizations have responded to the challenges analyzed in the first part. Introductory material, as well as several of the essays, provide some preliminary thoughts about the impact of the crisis year 2020 on the world of classical music. Classical Music Classical Classical Music: Contemporary Perspectives and Challenges will be a valuable and engaging resource for all readers interested in the development of the arts and classical music, especially academics, arts administrators and organizers, and classical music practitioners and audiences. Edited by Paul Boghossian Michael Beckerman Julius Silver Professor of Philosophy Carroll and Milton Petrie Professor and Chair; Director, Global Institute for of Music and Chair; Collegiate Advanced Study, New York University Professor, New York University This is the author-approved edition of this Open Access title. As with all Open Book publications, this entire book is available to read for free on the publisher’s website.