Lytton Strachey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Records of the Chicheley Plowdens A.D. 1590-1913; with Four

DUKE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY J ^e \°0 * \ RECORDS OF THE CHICHELEY PLOWDENS, a.d. 1590-1913 /{/w v » Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from hb Duke University Libraries https://archive.org/details/recordsofchichel01plow RECORDS it OF THE Chicheley Plowdens A.D. I59O-I9I3 With Four Alphabetical Indices, Four Pedigree Sheets, and a Portrait of Edmund, the great Elizabethan lawyer BY WALTER F. C. CHICHELEY PLOWDEN (Late Indian Army) PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION HEATH, CRANTON & OUSELEY LTD. FLEET LANE, LONDON, E. C. 1914 ?7 3AV CONTENTS PAGB Introduction ....... i PART I FIRST SERIES The Plowdens of Plowden ..... 6 SECOND SERIES The Chicheley Plowdens . .18 THIRD SERIES The Welsh Plowdens . .41 FOURTH SERIES The American Plowdens ..... 43 PART II CHAPTER I. Sir Edmund Plowden of Wanstead, Kt. (1590-1659) 51 II. Francis the Disinherited and his Descendants, the Plowdens of Bushwood, Maryland, U.S.A. 99 III. Thomas Plowden of Lasham .... 107 IV. Francis of New Albion and his Descendants in Wales . - .112 V. The first two James Plowdens, with some Account OF THE CHICHELEYS AND THE STRANGE WlLL OF Richard Norton of Southwick . .116 VI. The Rev. James Chicheley Plowden, and his Descendants by his Eldest Son, James (4), with an Account of some of his Younger Children . 136 v Contents CHAPTER PAGE VII. Richard and Henry, the Pioneers of the Family in India, and their Children . 151 VIII. The Grandchildren of Richard Chicheley, the H.E.I.C. Director . , . .176 IX. The Grandchildren of Trevor, by his Sons, Trevor (2) and George ..... 186 Conclusion . .191 VI EXPLANATION OF THE SHIELD ON COVER The various arms, twelve in number, in the Chicheley Plowden shield, reading from left to right, are : 1. -

Biographies and Autobiographies of Historians, Edited by Doug Munro and John G

7 Intersecting and Contrasting Lives: G.M. Trevelyan and Lytton Strachey Alastair MacLachlan This essay is about history and biography in two senses. First, it examines two parallel and intersecting, but contrasting lives: that of George Macaulay Trevelyan (b. 1876), probably the most popular historian and political biographer of early twentieth-century England – a Fellow and in old age the Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, an independent scholar for 25 years and, for 12 years, Regius Professor of Modern History – and that of his slightly younger Trinity protégé, Giles Lytton Strachey (b. 1880), a would-be academic rejected by the academy, who set himself up as a critical essayist and a historical gadfly – the writer credited with the transformation of a moribund genre of pious memorialisation into a ‘new’ style of biography. Second, the essay explores their approaches to writing nineteenth-century history and biography, and it assesses their works as products of similar but changing times and places: Cambridge and London from about 1900 to the 1930s.1 1 I shall therefore ignore Trevelyan’s later writings (he died in 1962), and concentrate on the biographies written by Strachey (S) and Trevelyan (T), with a focus on their nineteenth-century studies. 137 CLIO'S LIVES ‘Read no history’, advised Disraeli, ‘nothing but biography, for that is life without theory’. But ‘life without theory’ can be intellectually emaciated, and a comparative biography may have the advantage of kneading into the subject theoretical muscle sometimes absent in single lives, highlighting the points where the two lives intersected and what was common and what distinctive about them. -

Address to the Royal Geographical Society of London

: ADDRESSis- TO THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON; DELIVERED AT THE ANNIVERSARY MEETING ON THE 24th May, 1852. PRECEDED BY OBSERVATIONS ON PRESENTING THE ROYAL MEDALS OF THE YEAR. BY Sir R. I. MURCHISON, G.C.St.S., M.A., F.R.S., MEMBER OF THE ACADEMIES OF ST. PETERSBURG, BERLIN, COPENHAGEN; AND CORK. INST. OF FRANCE, &c., PRESIDENT. LONDON PRINTED BY W. CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET. 1852. PRESENTATION OF THE GOLD MEDALS AWARDED TO DR. JOHN RAE, OF THE HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY, AND CAPTAIN HENRY STRACHEY, OF THE HONOURABLE EAST INDIA COMPANY’S ENGINEERS. The Founder’s Gold Medal has been awarded by the Council to Dr. John Rae “ for his survey of Boothia under most severe privations in 1848, and for his recent explorations on foot, and in boats, of the coasts of Wollaston and Victoria Lands, by which very important additions have been made to the geography of the Arctic regions.” Dr. Rae’s survey of the inlet of Boothia in 1848 was unique in its kind. With a boldness never surpassed, he determined on wintering on the proverbially desolate shores of Repulse Bay, where, or in the immediate neighbourhood, one expedition of two ships had previously wholly perished, and two others were all but lost. There he main- tained his party on deer shot principally by himself, and spent ten months of an Arctic winter in a hut of stones, the locality not even yielding drift timber. With no other fuel than a kind of hay made of he his in the Andromeda tetragona , preserved men health, and thus enabled them to execute their arduous surveying journeys of upwards of 1000 miles round Committee Bay (the southern portion of Boothia Gulf) in the spring. -

English Men Oe Science %Xm Lroit

English Men oe Science THEIR NATURE AND NURTURE. »Y FRANCIS GALTON, F.R.S., AUTHOR OP " HEREDITARY GENIUS,” ETC. % x m l r o i t : MACMILLAN & CO. 1874. PREFACE. I u n d e r t o o k the inquiry of which this volume is the result, after reading the recent work of M. de Candolle,1 in which he analyses the salient events in the history of 200 scientific men who have lived during the two past centuries, deducing therefrom many curious conclusions which well repay the attention of thoughtful readers. It so happened that I myself had been leisurely engaged on a parallel but more ex tended investigation— namely, as regards men of ability of all descriptions, with the view of supplementing at some future time my work on Hereditary Genius. The object of that book 1 “ Histoire des Sciences et des Savants depuis deux Siecles.” Par Alphonse de Candolle. Corr. Inst. Acad. Sc. de Paris, &c. Geneve, 1873. was to assert the claims of one of what may be called the “ pre-efficients ” 1 of eminent men, the importance of which had been previously over looked ; and I had yet to work out more fully its relative efficacy, as compared with those of education, tradition, fortune, opportunity, and much else. It was therefore with no ordinary interest that I studied M. de Candolle’s work, finding in it many new ideas and much con firmation of my own opinions; also not a little criticism (supported, as I conceive, by very im perfect biographical evidence,)1 2 of my published views on heredity. -

Thirty Years' Work of the Royal Geo-Graphical Society Author(S): J

Thirty Years' Work of the Royal Geo-Graphical Society Author(s): J. Scott Keltie Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 49, No. 5 (May, 1917), pp. 350-372 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1779657 Accessed: 03-06-2016 09:09 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 143.89.105.150 on Fri, 03 Jun 2016 09:09:21 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms ( 350 ) THIRTY YEARS' WORK OF THE ROYAL GEO- GRAPHICAL SOCIETY J. Scott Keltie, LL.D. Read at the Meeting of the Society, 5 February 1917. I HAVE been urged to put together some reminiscences of my official con- nection with the Society during the last thirty-three years in the form of a paper to be given at one of the evening meetings, before I finally retire from the Society's service. I have thought it might be of some interest to put what I have to say in the form of a brief review of the varied work of the Society during the years of my connection with it, referring to some of the outstanding episodes that have marked the Society's evolution towards its present position and Lowther Lodge. -

Olivia from Bloomsbury to The

OLIVIAFROM BLOOMSBURY TO THENRF Marie-Claire Hamard Unrversité de Franche-Comté Dorothy Bussy, the author of Olivia, an autobiographical novel published in 1949 when she was in her eighties, has had an interesting destiny which illustrates many of the subtle diíñculties encountered by an inteliigent woman born in the Mid-Victorian period. She can be defined briefly as the daughter of Sir Richard Strachey, a general and scientist with great responsibilities in Rritish India until 1871, as an elder sister of Lytton Strachey the writer, and James Strachey the translator of Freud, as the wife of Simon Bussy, a @ed but neglected French painter, and as the translator and close friend of the French novelist André Gide. Thus her career can be seen as subordinate to the careen of the men around her. By the same standards, she could be considered to have had a very full life, firsí in London at Lancaster Gate, as a member of a remakbly inte1lectua.I family, then after 1903 at Roquebmne on the French Riviera among artists. She had a daughter, Janie, born in 1905, who was a constant joy, and her fhendship with Gide, stwck in 1918, introduced her into the world of the Nouvelle Revue Fran~aise.She, for her part, introduced her French friends to the artistic and intellectuai coterie of Bloomsbury. She played the part of an intermediary, passing every year fiom Roquebrune to London via Paris; she played it in print as Gide's main translator and also in her many letteis. Her correspondence with Gide has been published in full by the NRF and a selection by Odord University Press Gambert 1979; Tedeschi 1983), it is interesting to see in those letters the European network of inteliectuai relations to whom this woman without a 'salon' effectively belonged. -

Back Matter (PDF)

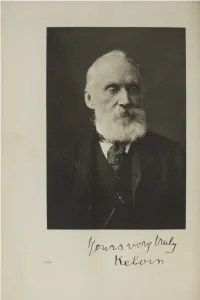

(pntns6 <ircjuf 1 9 0 7 [ 1 PBOCEEDINGS OF THE EOYAL SOCIETY. Series A, Vol. 81, Appendix, 1908. OBITUARY NOTICES OF FELLOWS DECEASED. P ages L ord K e l v in ......................................................................................................... iii—lxxvi Illustrated by three photogravure portraits by Annan and Sons: the earlier one, p. xxxii, from a daguerreotype, represents Lord Kelvin about 1855, at the age of th irty ; the middle one, p. lxiv, is from a negative by Fergus (now J. Stewart), of Largs, of date 1877 ; the later one, facing p. i, is from a negative by Dickinsons, New Bond Street, W., taken in 1907. WILLIAM THOMSON, LOBD KELVIN. Born in Belfast, June 26, 1824. Entered University of Glasgow, 1834. Entered at Peterhouse, Cambridge, October 1841. B.A. and Fellow of Peterhouse, 1845. Professor of Natural Philosophy at Glasgow, 1846. Fellow of the Koyal Society, 1851; Eoyal Medallist, 1856 ; Copley Medallist, 1883. Marriage to Miss Margaret Crum (deceased 1870), 1852. First Atlantic Cables laid, 1857-58. Permanent Atlantic Cables laid, 1865-66. Created a Knight, 1866 ; G.C.V.O., 1896. University of Glasgow removed to Gilmore Hill, 1870. President of the British Association, Edinburgh, 1871. Ee-elected Fellow of Peterhouse, 1872. Marriage to Miss Frances Anna Blandy, 1874. Elected Foreign Associate Member of the Institute of France, 1877. Created Knight of the Prussian Order Pour le , 1884. Baltimore Lectures, 1884 ; enlarged edition, 1904. President of the Eoyal Society of Edinburgh, 1886-9 ; 1895-1907. Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour of France, 189 . Created a Peer of Great Britain, as Baron Kelvin of Largs, 1892. -

Death of Sir Clements Markham Source: the Geographical Journal, Vol

Death of Sir Clements Markham Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 47, No. 3 (Mar., 1916), pp. 161-176 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1779297 Accessed: 29/11/2009 19:58 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) and Blackwell Publishing are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal. http://www.jstor.org The Geographical Journal. -

Review 2005/2006

Review 2005/2006 Review 2005/2006 2 Preface by the Chairman of the Trustees 4 Foreword by the Director 6 2005/2006 Highlights 8 Extending and Broadening Audiences 14 Developing the Collection 20 Increasing Understanding of Portraiture and the Collection 28 Maximising Financial Resources 33 Developing Staff 34 Improving Services 38 Supporters 40 Financial Report 44 Acquisitions 50 Research Activities 51 Exhibitions 52 Staff William Shakespeare?, known as the Chandos Portrait attributed to John Taylor, c.1600–10 Front cover J.K. Rowling by Stuart Pearson Wright, 2005 Commissioned by the Trustees and made possible by funding from BP Back cover Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland by Sir Peter Lely, c.1664 2 Preface by the Significant anniversaries do not come all that the highest number of visits both for the often. Although the opportunity to celebrate is BP Portrait Award and for the Schweppes Chairman of very welcome, the 150th Anniversary also offers Photographic Prize exhibitions, as well as a the Trustees a chance to take stock and to look forward with high attendance for the BBC collaboration determination. There is a great deal to applaud: The World’s Most Photographed. from a record year for visitors to success in the development of research, the Gallery moves These successes in London are matched by our from strength to strength. increasingly important outreach activities and national programme work around the country, Much of the past year has been taken up including our partnership with the North East with preparation for the 150th Anniversary Hub, our collaborations in cities such as programme. -

The Construction of Modern Timekeeping

THE CONSTRUCTION OF MODERN TIMEKEEPING THE CONSTRUCTION OF MODERN TIMEKEEPING IN THE ANGLO-AMERICAN WORLD, 1876-1913 BY SCOTT JOHNSTON, B.A. (Hons.), M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Scott Johnston, July 2018 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2018) Hamilton, Ontario (History) TITLE: The Construction of Modern Timekeeping in the Anglo-American World, 1876- 1913 AUTHOR: Scott Johnston, B.A. (Hons.) (Brock University), M.A. (University of Waterloo) SUPERVISOR: Professor S. Heathorn NUMBER OF PAGES: x, 351 ii Lay Abstract This dissertation asks why the system of time measurement set up towards the end of the nineteenth century took the form that it did. While partially dependent on new technologies such as railways and telegraphs, timekeeping was shaped more directly by the cultural context of the individuals involved. The dissertation uses the 1884 International Meridian Conference as a case study to suggest that time reform was driven by professional norms more than by national interest or changes in technology. Astronomers and engineers came to the conference with very different visions for modern timekeeping. Indeed, questions about the very nature of accurate time was at the heart of the debate: was time a public good, a commodity, or a specialized tool? The answers to these questions depended heavily on one’s profession, and as a result the standard time system that emerged was far from inevitable, and in fact remained incomplete. iii Abstract This dissertation asks why the system of time measurement set up towards the end of the nineteenth century took the form that it did. -

Only One Himalaya: Perspectives on the Himalaya As a Regional Science

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 16 Number 1 Himalayan Research Bulletin No. 1 & Article 4 2 1996 Only One Himalaya: Perspectives on the Himalaya as a Regional Science Rasoul B. Sorkhabi Arizona State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Sorkhabi, Rasoul B.. 1996. Only One Himalaya: Perspectives on the Himalaya as a Regional Science. HIMALAYA 16(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol16/iss1/4 This Research Report is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Only One Himalaya: Perspectives on the Himalaya as a Regional Science Rasoul B. Sorkhabi Department of Geology, Arizona State University "The first step toward devising a strategy for Planet Earth is for the nations to accept a collective responsibility for discovering much more--much more--about the natural system and how it is affected by man's activities and vice versa. This implies cooperative monitoring, research and study on an unprecedented scale. It implies an intensive world-wide network for the systematic exchange of knowledge and experience." Barbara Ward and Rene Dubos in Only One Earth (1972) Introduction denudation) suggest that the Himalaya-Tibetan region There is only one Himalaya. Nature being so may be the highest and largest culmination of the creative, each part of our planet is unique in one way or earth's crust since the "Pan-African" mountains of some another. -

Dr. N L Dongre FRGS, London

Dr. N L Dongre FRGS, London Living a Life of Value 1 ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY, LONDON ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY (WITH THE INSTITUTE OF BRITISH GEOGRAPHERS) “The most incomprehensible thing about the world is that it is comprehensible.” - Albert Einstein Dr. N L Dongre, Indian Police Service (IPS) Inspector General of Police, Madhya Pradesh Fellow of Royal Geographical Society, London (FRGS) Doctor of Letters (D.Litt) and Ph.D) The true spirits of delight, the exaltation, the sense of being more than expected are the touchstone of the highest excellence in my life. Royal Geographical society, London conferred me the eminent Fellowship of the Society. The backbone of the society is its Fellowship, which is made up of the most eminent Earth Scientist (Geographers) from the world; fellows are elected through a peer review process that culminates in a vote by existing Fellows on the basis of excellence in Earth Science and Geosciences. 2 The Royal Geographical Society is a learned society, founded in 1830 with the name Geographical Society of London for the advancement of geographical science, under the patronage of King William IV. It absorbed the 'Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa' (founded by Sir Joseph Banks in 1788), the Raleigh Club and the Palestine Association. It was given a Royal charter by Queen Victoria in 1859. History Founder members of the Society include Sir John Barrow, Sir John Franklin and Francis Beaufort. It has been a key associate and supporter of many famous explorers and expeditions, including those of: Charles Darwin David Livingstone Scott of the Antarctic Richard Francis Burton John Hanning Speke Henry Morton Stanley Ernest Shackleton Today the Society is a leading world centre for geographical learning - supporting education, teaching, research and scientific expeditions, as well as promoting public understanding and enjoyment of geography.