Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bloody Crossroads African-Americans and the Bork Nomination: a Bibliographic Essay J

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University Selected Speeches J. Clay Smith, Jr. Collection 1-11-1992 Bloody Crossroads African-Americans and The Bork Nomination: A Bibliographic Essay J. Clay Smith Jr. Follow this and additional works at: http://dh.howard.edu/jcs_speeches Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Smith, J. Clay Jr., "Bloody Crossroads African-Americans and The Bork ominN ation: A Bibliographic Essay" (1992). Selected Speeches. Paper 151. http://dh.howard.edu/jcs_speeches/151 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the J. Clay Smith, Jr. Collection at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Speeches by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 173 "Bloody Crossroads" AFRICAN-AMERICANS and the BORK NOMINATION: A BIBLIOGRAPHIC ESSAY J. Clay Smith, Jr.* Two diverging traditions in the mainstream of Western political thought-one "liberal," the other "conservative"-have competed, and still_ compete, for control of the democratic process and of the American constitutional system; both have controlled the direction of our judicial policy at one time or another. - Alexander M. Bicke11 The clash over my nomination was simply one battle in-this long-running war for control of our legal culture. - Robert H. Bork2 On July 1, 1987 President Ronald Reagan announced his nomination of Judge Robert H. Bork to succeed Justice Lewis Powell * Professor of Law, Howard University School of Law. Alexander M. Bickel, The Morality Of Consent 3 (1975), hereafter, Morality Of Consent. 2 Robert H. Bork, The Tempting of America The Political Seduction of the Law 2 (1990), hereafter, Tempting of America. -

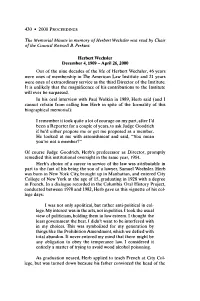

Memorial Minute in Memory of Wechsler

430 • 2000 PROCEEDINGS The Memorial Minute in memory of Herbert Wechsler was read by Chair of the Council Roswell B. Perkins. Herbert Wechsler December 4, 1909 - April 26, 2000 Out of the nine decades of the life of Herbert Wechsler, 46 years were ones of membership in The American Law Institute and 21 years were ones of extraordinary service as the third Director of the Institute. It is unlikely that the magnificence of his contributions to the Institute will ever be surpassed. In his oral interview with Paul Wolkin in 1989, Herb said (and I cannot refrain from calling him Herb in spite of the formality of this biographical memorial): I remember it took quite a lot of courage on my part, after I'd been a Reporter for a couple of years, to ask Judge Goodrich if he'd either propose me or get me proposed as a member. He looked at me with astonishment and said, "You mean you're not a member?" Of course Judge Goodrich, Herb's predecessor as Director, promptly remedied this institutional oversight in the same year, 1954. Herb's choice of a career in service of the law was attributable in part to the fact of his being the son of a lawyer, Samuel Wechsler. Herb was born in New York City, brought up in Manhattan, and entered City College of New York at the age of 15, graduating in 1928 with a degree in French. In a dialogue recorded in the Columbia Oral History Project, conducted between 1978 and 1982, Herb gave us this vignette of his col lege days: I was not only apolitical, but rather anti-political in col lege. -

Hearing Before The

RETURN TO FILES CRIMINAL RULES COMUITTEE 207 United States- Supreme Court Copy for Mr. AlexArnder Holtzoff, Secretary. Tuesday, September 9, 1941. Hearing Before the ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON RULES OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT WASHINGTON, D. C. GEO. L.HART HART & DICE EDWIN DICE SHORTHAND REPORTERS TELEPHONES LLOYD L. HARKINS. 416 FIFTH ST. N. W. NATIONAL 0343 OFFICE MANAGER SUITE 301-307 COLUMBIAN BLDG. NATIONAL 0344 WASHINGTON. D. C. 239 CONTEXTS. Tuesday, September 9, 1941. Rule, 8 -240 Rule, 9 --------------------------------------------- Rule ,10 5338,355 Rule,20 -394 Rule,21 -405 Rule,2 - 457 Rule.29 ---------------------------------------------- 458 Rule,30 ---------------------------------------------- 458 Rule,34 --------------------------------------------- 465 -- oo0oo-- lbb 240 NJC ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON RULES OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT WASHINGTON, D. C. Tuesday, September 9, 1941. The Advisory Committee met at 10 otclock a.m., in room 147-B, Supreme Court Building, Washington, D. C., Arthur T. Vanderbilt presiding. Present: Arthur T. Vanderbilt, Chairman; James J.Robinson, Reporter; Alexander Holtzoff, Secretary; George James Burke, Frederick E. Crane, Gordon Dean, George H. Dession, Sheldon Glueck, George Z. Medalie, Lester B. Orfield, Murray Seasongood, J. 0. Seth, Herbert Wechsler, G. Aaron Youngquist, George F. Longsdorf, John B. Waite. The Chairman. All right, gentlemen. Let us proceed. I believe we are on Rule 8, page 3, sub-heading (b). Mr. Holtzoff. I have a question as to the phraseology of that. When you speak of filing one of the following notices, pleas, or motions, that seems to convey the impression, which probably was not intended, that there must be a written plea, because you cannot file an oral plea. -

Herbert Wechsler and the Political History of the Criminal Law Course

The Anti-Case Method: Herbert Wechsler and the Political History of the Criminal Law Course Anders Walker* This article is the first to cover the transformation in criminal law teaching away from the case method and towards a more open-ended philosophicalapproach in the 1930s. It makes three contributions. One, it shows how Columbia law professor Herbert Wechsler revolutionized the teaching of criminal law by de-emphasizing cases and including a variety of non-case-relatedmaterial in his 1940 text Criminal Law and Its Administration. Two, it reveals that at least part of Wechsler's intention behind transforming criminal law teaching was to undermine Langdell's case method, which he blamed for producing a "closed- system" view of the law that contributed to the Supreme Court's destruction of the first half of the New Deal. Three, it shows that Wechsler's text inspired an entire generation of law teachers who believed that criminal law should be taught as a "liberal arts" course, precisely so that law students would not become criminal lawyers. The legal academy's disdain for criminal practice, this article concludes, allowed scholars like Wechsler to introduce innovations in criminal law teaching that became a subsequent model for law teaching generally in the United States during the latter halfof the twentieth century. Few areas of legal practice command more popular attention than criminal law.' Yet, the manner in which criminal law is taught in law schools has relatively little to do with preparing students for criminal practice. Beginning in the 1930s, law schools intentionally reconfigured their criminal law courses so that students would not become criminal lawyers. -

Hart and Wechsler's the Federal Courts and the Federal System By

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 62 | Issue 4 Article 5 1974 Hart and Wechsler's The edeF ral Courts and the Federal System by Paul M. Bator, Paul J. Mishkin, David L. Shapiro, and Herbert Weschler George W. Liebmann Frank, Bernstein, Conoway and Goldman Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Liebmann, George W. (1974) "Hart and Wechsler's The eF deral Courts and the Federal System by Paul M. Bator, Paul J. Mishkin, David L. Shapiro, and Herbert Weschler," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 62 : Iss. 4 , Article 5. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol62/iss4/5 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Special Book Review HART AND WEcHLsr's, Tim FEDERAL CouRTs AND TEE FEDERAL SYsrEm (2d ed. .1973) by Paul M. Bator, Paul J. Mishkin, David L. Shapiro and HerbertWechsler. Mineola, New York: Foundation Press, Inc., 1973. Certainly it is the height of presumption to undertake a review of this new edition of a work which has come to be regarded by courts and practitioners, as well as by the academic fraternity, as the most penetrating delineation and description of problems of federal juns- diction and of the allocation of power between state and national courts. -

Herbert Wechsler, the Model Penal Code, and the Uses of Revenge Anders Walker Saint Louis University School of Law

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Saint Louis University School of Law Research: Scholarship Commons Saint Louis University School of Law Scholarship Commons All Faculty Scholarship 2009 American Oresteia: Herbert Wechsler, the Model Penal Code, and the Uses of Revenge Anders Walker Saint Louis University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/faculty Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Walker, Anders, American Oresteia: Herbert Wechsler, the Model Penal Code, and the Uses of Revenge. Wisconsin Law Review, Vol. 2009, p. 1018, 2009. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. AMERICAN ORESTEIA HERBERT WECHSLER , THE MODEL PENAL CODE , & THE USES OF REVENGE ANDERS WALKER ABSTRACT The American Law Institute recently revised the Model Penal Code’s sentencing provisions, calling for a renewed commitment to proportionality based on the gravity of offenses, the “blameworthiness” of offenders, and the “harms done to crime victims.” Already, detractors have criticized this move, arguing that it replaces the Code’s original commitment to rehabilitation with a more punitive attention to retribution. Yet, missing from such calumny is an awareness of retribution’s subtle yet significant role in both the drafting and enactment of the first Model Penal Code (MPC). This article recovers that role by focusing on the retributive views of its first Reporter, Columbia Law Professor Herbert Wechsler. -

A Process of Denial: Bork and Post-Modern Conservatism

A Process of Denial: Bork and Post-Modern Conservatism James Boyle· [I]t is naive to suppose that the [Supreme] Court's present difficul ties could be cured by appointing Justices determined to give the Constitution "its true meaning," to work at "finding the law" instead of reforming society. The possibility implied by these com forting phrases does not exist. History can be of considerable help, but it tells us much too little about the specific intentions of the men who framed, adopted and ratified the great clauses. The record is incomplete, the men involved often had vague or even conflicting intentions, and no one foresaw, or could have foreseen, the disputes that changing social conditions and outlooks would bring before the Court. Robert Bork 1 INTRODUCTION As you might guess from the title, Robert Bork's latest work, The Tempting ofAmerica, 2 is a book about the Fall-both America's and Mr. Bork's own. It will not surprise many readers to. find that the two are linked, or that the "temptation" to which Mr. Bork refers is that of poli tics. In particular, he warns us of an increasing politicization of the American legal system. This politicization is caused primarily by judges who desert the original understanding of the Constitution and, under the guise of "interpretation," attempt instead to impose their own individual notions of justice on the cases before them. Mr. Bork conveys these messages in a book which is part autobiography and part legal theory, inspired by the ordeal which brought him to fame: the Senate's judicial confirmation process. -

Toward Neutral Principles of Stare Decisions in Tort Law

South Carolina Law Review Volume 58 Issue 2 Article 4 Winter 2006 Toward Neutral Principles of Stare Decisions in Tort Law Victor E. Schwartz Shook, Hardy & Bacon (Washington, D.C.) Cary Silverman Shook, Hardy & Bacon (Washington, D.C.) Phil Goldberg Shook, Hardy & Bacon (Washington, D.C.) Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Victor E. Schwartz, et. al., Toward Neutral Principles of Stare Decisions in Tort Law, 58 S. C. L. Rev. 317 (2006). This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Schwartz et al.: Toward Neutral Principles of Stare Decisions in Tort Law TOWARD NEUTRAL PRINCIPLES OF STARE DECISIS IN TORT LAW* VICTOR E. SCHWARTZ** CARY SILVERMAN*** PHIL GOLDBERG"... 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................. 319 II. THE ROLE OF STARE DECISIS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF COMMON LAW . 320 A. The Doctrine of Stare Decisis ........................... 320 B. The Development of Tort Law Under Stare Decisis ............. 323 C. Initiating a Review of Tort Law: Most Judges Wait to Be Asked... 326 11. NEUTRAL PRINCIPLES OF STARE DECISIS IN TORT LAW .............. 327 A. Principles of Change .................................... 329 1. A Significant Shift in the Legal Foundation Underlying a Tort Law Rule May Warrant a Departure from Stare Decisis ................................... 329 2. A Tort Law Rule that Is No Longer Compatible with the Realities of Modern Society Must Shift to Meet Changing Times ............................. -

Robert Bork: Intellectual Leader of the Legal Right

McGinnis: Robert Bork: Intellectual Leader of the Legal Right Robert Bork: Intellectual Leader of the Legal Right John 0. McGinnist There were two important movements in conservative and libertarian legal thought in the latter part of the twentieth cen- tury. One was law and economics. The other was originalism. Judge Robert Bork was unique in being at the intellectual center of both of them. In law and economics, he applied economic analysis in book-length form to antitrust law, showing how the simple insights of price theory could generate a fully coherent body of legal doctrine., In constitutional theory, he made a cru- cial first step toward originalism by arguing that neutral princi- ples must be derived neutrally and thus from the text of the Constitution.2 As a result of these distinct enterprises, he was the most important legal scholar on the right in the last fifty years. These contributions were of substantially different kinds. In antitrust, he mapped an entire field. In constitutional law, he discovered or rediscovered a methodology but left it to others to reticulate and refine his insight. While some have suggested that his claim to being a great scholar rests only on his contribu- tion to antitrust,3 this assessment is mistaken. The pathfinder can be as great as even the most expert surveyor. 4 Both are cru- cial to the progress of any discipline. t George C. Dix Professor in Constitutional Law, Northwestern University School of Law. 1 See, for example, Robert H. Bork, The Antitrust Paradox: A Policy at War with Itself 116-33 (Basic Books 1978). -

229 WECHSLER's TRIUMPH David A. Anderson* the Constitutional

2 ANDERSON 229-252 (DO NOT DELETE) 11/14/2014 3:41 PM WECHSLER’S TRIUMPH David A. Anderson* The constitutional landmark called New York Times v. Sullivan 1 was the result of what Paul Horwitz calls a “concatenation of circumstances.”2 One of those was the momentum of the civil rights movement, which was at its height when the case was decided. Montgomery, Alabama, was the site of the bus boycott that launched the movement and the career of Dr. Martin Luther King.3 The Freedom Riders of 1961 and lunch-counter sit- ins of 1963 had heightened Northern awareness of the movement. Photos of marchers being attacked by police with fire hoses and dogs in Birmingham in 1963 shocked the nation. The case arose from an ad which invoked names of celebrities in an appeal for contributions to support Dr. King’s organization.4 It was decided by a Supreme Court that had already played a large role in the struggle against segregation in the South, beginning in 1954 with the case ordering desegregation of schools,5 and continuing with such cases as the Little Rock school desegregation case in 19586 and the sit-in cases starting in 1961.7 The main defendant was the most influential newspaper in America, with a long history of leadership on matters of racial justice.8 Its extensive coverage of racial incidents in the South in the early 1960s had angered many white Southerners. The plaintiff, Montgomery Commissioner L. B. Sullivan, was to many a symbol of racism. He was a member of the Ku * Fred & Emily Marshall Wulff Centennial Chair in Law at the University of Texas School of Law. -

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Law As Applied to Radio City Music Hall*

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Law As Applied To Radio City Music Hall* I. INTRODUCTION The preservation of historic and architectural landmarks is a valid and necessary governmental function. As Justice Douglas wrote in Berman v. Parker,1 "[i]t is within the power of the legislature to determine that the community should be beautiful as well as healthy, spacious as well as clean, well-balanced as well as carefully patrolled." 2 It is an equally proper legislative determination that a community's cultural heritage must be protected. In the Historic Sites, Buildings and Antiquities Act of 1935, 3 Congress declared that there exists "a national policy to preserve for public use his- toric sites, buildings, and objects of national significance for the in- spiration and benefit of the people of the United States." 4 Simi- larly, a state or municipality clearly has the power to enact laws in order to preserve architectural masterpieces and structures of his- toric or aesthetic importance and thus to protect the general pub- lic's cultural welfare. The two major approaches to landmarks preservation, eminent domain 5 and government regulation, have significantly different * The author is grateful to Professors Curtis J. Berger, John M. Kernochan, Stephen A. Lefkowitz, and Herbert Wechsler of the Columbia University School of Law for generously offering both criticism and encouragement in the preparation of this article. This article was originally prepared for Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts (New York) and was published in somewhat different form in Volume IV, Issue 4 (1979) of its quarterly journal, ART AND THE LAW. -

Neutral Principles: a Retrospective

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 50 Issue 2 Issue 2 - Symposium: Defining Article 12 Democracy for the Next Century 3-1997 Neutral Principles: A Retrospective Barry Friedman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Barry Friedman, Neutral Principles: A Retrospective, 50 Vanderbilt Law Review 503 (1997) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol50/iss2/12 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neutral Principles: A Retrospective Barry Friedman* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 503 II. THE DEBATE OVER NEUTRAL PRINCIPLES ......................... 507 A. The Genesis of the Neutral PrinciplesDebate ....... 507 B. A Neutral Principle,But Not "Colorblindness".... 513 C. Substantive (Rather than Formal)Neutrality ....... 516 D. Public Opinion and Neutrality.............................. 525 III. NEUTRAL PRINCIPLES AND AFFIRMATIVE ACTION ............. 530 I. INTRODUCTION Once upon a time, Enlightenment ideals prevailed across the land. Neutrality, objectivity, and reason were accepted as the firma- ments of Supreme Court decisionmaking. "Americans tend[ed] to believe that 'playing fair' [meant] making everyone play by the same rules, and