Somatic Symptom Disorder in Dermatology James L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOMATIC SYMPTOM, BODILY DISTRESS and RELATED DISORDERS in CHILDREN and ADOLESCENTS 2019 Edition

IACAPAP Textbook of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Chapter CHILD PSYCHIATRY & PEDIATRICS I.1 SOMATIC SYMPTOM, BODILY DISTRESS AND RELATED DISORDERS IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS 2019 edition Olivia Fiertag, Sharon Taylor, Amina Tareen & Elena Garralda Olivia Fiertag MBChB, MRCPsych, PGDip CBT Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist. Honorary Clinical Researcher, HPFT NHS Trust & collaboration with Imperial College London, UK Conflict of interest: none declared Sharon Taylor BSc, MBBS, MRCP, MRCPsych, CASLAT, PGDip Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist CNWL Foundation NHS Trust & Honorary Senior Clinical Lecturer Imperial College London, UK. Joint Program Director, St Mary’s Child Sick Girl. Psychiatry Training Scheme Christian Krogh, Conflict of interest: none (1880/1881) National declared Gallery of Norway This publication is intended for professionals training or practicing in mental health and not for the general public. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Editor or IACAPAP. This publication seeks to describe the best treatments and practices based on the scientific evidence available at the time of writing as evaluated by the authors and may change as a result of new research. Readers need to apply this knowledge to patients in accordance with the guidelines and laws of their country of practice. Some medications may not be available in some countries and readers should consult the specific drug information since not all dosages and unwanted effects are mentioned. Organizations, publications and websites are cited or linked to illustrate issues or as a source of further information. This does not mean that authors, the Editor or IACAPAP endorse their content or recommendations, which should be critically assessed by the reader. -

Guidelines for Treating Dissociative Identity Disorder in Adults, Third

This article was downloaded by: [208.78.151.82] On: 21 October 2011, At: 09:20 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Trauma & Dissociation Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wjtd20 Guidelines for Treating Dissociative Identity Disorder in Adults, Third Revision International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation Available online: 03 Mar 2011 To cite this article: International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation (2011): Guidelines for Treating Dissociative Identity Disorder in Adults, Third Revision, Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 12:2, 115-187 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2011.537247 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Somatoform Disorders – September 2017

CrackCast Show Notes – Somatoform Disorders – September 2017 www.canadiem.org/crackcast Chapter 103 – Somatoform disorders Episode overview 1. List 5 somatic symptom and related disorders 2. List 5 common presentations of conversion disorders 3. List 6 ddx of somatic symptom disorder Wisecracks 1. List 6 organic diseases that may be mistaken for somatoform disorders 2. Describe the treatment goals of somatoform disorders Somatoform disorders as a diagnosis has been eliminated from the DSM-5! The patient with functional neurological symptom disorder, what was termed conversion disorder previously, requires a careful and complete neurological examination. Rather than miss the subtle presentation of a neurological disorder, it may be appropriate to perform imaging and obtain neurological and psychiatric consultation. Do not assume that the patient with neurological deficits has a psychiatric disorder. Success with the SSD patient depends on establishing rapport with the patient and legitimizing their complaints to avoid a dysfunctional physician-patient interaction. • Avoid telling the SSD patient “it is all in your head” or “there is nothing wrong with you.” These patients are very sensitive to the idea that their suffering is being dismissed. • A useful approach is to discuss recent stressors with the patient and suggest to them that at times our bodies can be smarter than we are, telling us with physical symptoms that we need assistance. This approach alone may transform the ED visit from a standoff between physician and patient, to a grateful patient who develops greater insight and is amenable to referral. • Avoid prescribing unnecessary or addictive medications to the SSD patient. • If you suspect a diagnosis of SSD, refer the patient to primary care or psychiatry for further evaluation and treatment. -

Psychopathology and Somatic Complaints: a Cross-Sectional Study with Portuguese Adults

healthcare Article Psychopathology and Somatic Complaints: A Cross-Sectional Study with Portuguese Adults Joana Proença Becker 1,*, Rui Paixão 1 and Manuel João Quartilho 2 1 Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, University of Coimbra, 3000-115 Coimbra, Portugal; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, 3000-548 Coimbra, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +351-910741887 Abstract: (1) Background: Functional somatic symptoms (FSS) are physical symptoms that cannot be fully explained by medical diagnosis, injuries, and medication intake. More than the presence of unexplained symptoms, this condition is associated with functional disabilities, psychological distress, increased use of health services, and it has been linked to depressive and anxiety disorders. Recognizing the difficulty of diagnosing individuals with FSS and the impact on public health systems, this study aimed to verify the concomitant incidence of psychopathological symptoms and FSS in Portugal. (2) Methods: For this purpose, 93 psychosomatic outpatients (91.4% women with a mean age of 53.9 years old) and 101 subjects from the general population (74.3% women with 37.8 years old) were evaluated. The survey questionnaire included the 15-item Patient Health Questionnaire, the 20-Item Short Form Survey, the Brief Symptom Inventory, the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale, and questions on sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. (3) Results: Increases in FSS severity were correlated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. The findings also suggest that increased rates of FSS are associated with lower educational level and Citation: Becker, J.P.; Paixão, R.; female gender. -

Days out of Role and Somatic, Anxious-Depressive, Hypo-Manic, and Psychotic-Like Symptom Dimensions in a Community Sample of Young Adults Jacob J

Crouse et al. Translational Psychiatry (2021) 11:285 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01390-y Translational Psychiatry ARTICLE Open Access Days out of role and somatic, anxious-depressive, hypo-manic, and psychotic-like symptom dimensions in a community sample of young adults Jacob J. Crouse 1, Nicholas Ho 1,JanScott 1,2,3,4, Nicholas G. Martin 5, Baptiste Couvy-Duchesne 5,6,7, Daniel F. Hermens 8,RichardParker 5, Nathan A. Gillespie 9, Sarah E. Medland 5 and Ian B. Hickie 1 Abstract Improving our understanding of the causes of functional impairment in young people is a major global challenge. Here, we investigated the relationships between self-reported days out of role and the total quantity and different patterns of self-reported somatic, anxious-depressive, psychotic-like, and hypomanic symptoms in a community-based cohort of young adults. We examined self-ratings of 23 symptoms ranging across the four dimensions and days out of role in >1900 young adult twins and non-twin siblings participating in the “19Up” wave of the Brisbane Longitudinal Twin Study. Adjusted prevalence ratios (APR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) quantified associations between impairment and different symptom patterns. Three individual symptoms showed significant associations with days out of role, with the largest association for impaired concentration. When impairment was assessed according to each symptom dimension, there was a clear stepwise relationship between the total number of somatic symptoms and the 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; likelihood of impairment, while individuals reporting ≥4 anxious-depressive symptoms or five hypomanic symptoms had greater likelihood of reporting days out of role. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for Research

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic criteria for research World Health Organization Geneva The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations with primary responsibility for international health matters and public health. Through this organization, which was created in 1948, the health professions of some 180 countries exchange their knowledge and experience with the aim of making possible the attainment by all citizens of the world by the year 2000 of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. By means of direct technical cooperation with its Member States, and by stimulating such cooperation among them, WHO promotes the development of comprehensive health services, the prevention and control of diseases, the improvement of environmental conditions, the development of human resources for health, the coordination and development of biomedical and health services research, and the planning and implementation of health programmes. These broad fields of endeavour encompass a wide variety of activities, such as developing systems of primary health care that reach the whole population of Member countries; promoting the health of mothers and children; combating malnutrition; controlling malaria and other communicable diseases including tuberculosis and leprosy; coordinating the global strategy for the prevention and control of AIDS; having achieved the eradication of smallpox, promoting mass immunization against a number of other -

(Or Body Dysmorphic Disorder) and Schizophrenia: a Case Report

CASE REPORT Afr J Psychiatry 2010;13:61-63 Delusional disorder-somatic type (or body dysmorphic disorder) and schizophrenia: a case report BA Issa Department of Behavioural Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Ilorin, Nigeria Abstract With regard to delusional disorder-somatic subtype there may be a relationship with body dysmorphic disorder. There are reports that some delusional disorders can evolve to become schizophrenia. Similarly, the treatment of such disorders with antipsychotics has been documented. This report describes a case of delusional disorder - somatic type - preceding a psychotic episode and its successful treatment with an antipsychotic drug, thus contributing to what has been documented on the subject. Key words: Delusional disorder; Somatic; Body dysmorphic disorder; Schizophrenia Received: 14-10-2008 Accepted: 03-02-2009 Introduction may take place. While some successes have been reported, The classification of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is the general consensus is that most cases need psychiatric controversial; whereas BDD is classified as a somatoform rather than surgical intervention and that surgery may disorder, its delusional variant is classified as a psychotic seriously worsen the mental disorder in the longer term. 7 disorder. 1,2 This psychotic variant is also referred to as A previous or family history of psychotic disorder is delusional disorder somatic type. It is sometimes very difficult uncommon and in younger patients, a history of substance to distinguish cases of delusional disorder of somatic subtype abuse or head injury is frequent. 8 Although anger and hostility from severe somatization disorder, and claims have been are commonplace, shame, depression, and avoidant behavior made that there is a continuum between these illnesses. -

5 Allergic Diseases (And Differential Diagnoses)

Chapter 5 5 Allergic Diseases (and Differential Diagnoses) 5.1 Diseases with Possible IgE Involve- tions (combination of type I and type IVb reac- ment (“Immediate-Type Allergies”) tions). Atopic eczema will be discussed in a separate section (see Sect. 5.5.3). There are many allergic diseases manifesting in The maximal manifestation of IgE-mediated different organs and on the basis of different immediate-type allergic reaction is anaphylax- pathomechanisms (see Sect. 1.3). The most is. In the development of clinical symptoms, common allergies develop via IgE antibodies different organs may be involved and symp- and manifest within minutes to hours after al- toms of well-known allergic diseases of skin lergen contact (“immediate-type reactions”). and mucous membranes [also called “shock Not infrequently, there are biphasic (dual) re- fragments” (Karl Hansen)] may occur accord- action patterns when after a strong immediate ing to the severity (see Sect. 5.1.4). reactioninthecourseof6–12harenewedhy- persensitivity reaction (late-phase reaction, LPR) occurs which is triggered by IgE, but am- 5.1.1 Allergic Rhinitis plified by recruitment of additional cells and 5.1.1.1 Introduction mediators.TheseLPRshavetobedistin- guished from classic delayed-type hypersensi- Apart from being an aesthetic organ, the nose tivity (DTH) reactions (type IV reactions) (see has several very interesting functions (Ta- Sect. 5.5). ble 5.1). It is true that people can live without What may be confusing for the inexperi- breathing through the nose, but disturbance of enced physician is familiar to the allergist: The this function can lead to disease. Here we are same symptoms of immediate-type reactions interested mostly in defense functions against are observed without immune phenomena particles and irritants (physical or chemical) (skin tests or IgE antibodies) being detectable. -

Hypochondriasis and Somatization Disorder

Ch14.qxd 28/6/07 1:36 PM Page 152 14 Hypochondriasis and Somatization Disorder Don R. Lipsitt CONTENTS 14.1 The Concept of Somatization . 153 14.2 Classification . 154 14.2.1 From DSM-I to DSM-III . 154 14.2.2 Case History (Part 1). 155 14.3 Diagnosis . 156 14.3.1 Hypochondriasis . 156 14.3.2 Somatization Disorder . 160 14.3.3 Case History (Part 2). 163 14.4 The Consultation-Liaison Psychiatrist’s Role in Somatization . 163 14.5 Conclusion . 164 On a busy day in a general physician’s office, perhaps 50% or more of the patients with physical complaints will have no definitive explanation for their ailment (Kroenke and Mangelsdorff, 1989). The patients present with distress from fatigue, chest pain, cough, back pain, shortness of breath, and a host of other painful or worrisome bodily concerns. For most, the physician’s expressing interest, taking a thorough history, doing a physical examination, and offering reassurance, a mod- est intervention, or a pharmacologic prescription suffices to assuage the patient’s pain, anxiety, and physical distress. But for some, these simple measures fall short of their expected result, marking the beginning of what may become a chronic search for relief, including frequent anxiety-filled visits to more than one physician, and in extreme cases even multiple hospitalizations and possibly surgery. The longer and more persistently this pattern appears, the more likely it will generate referrals to specialists for expert consultation, greater frustration in both the primary physician and the patient, and ultimately dysfunctional patient–physician relationships with inappropriate labeling of the patient as a “problem” or “difficult” patient, and perhaps even worse (Lipsitt, 1970). -

Resistant Somatoform Symptoms: Try CBT and Antidepressants. Preferred Strategy for 'Mismatched' Category of Illnesses

Inova Health System IDEAS: Inova Digital e-ArchiveS Psychiatry Articles Psychiatry 2-2007 Resistant Somatoform Symptoms: Try CBT and Antidepressants. Preferred Strategy for ‘Mismatched’ Category of Illnesses. Michael J. Marcangelo MD Thomas N. Wise MD Inova Health System, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://www.inovaideas.org/psychiatry_articles Part of the Psychiatry and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Marcangelo, M.J. & Wise, T.N. (2007). Resistant somatoform symptoms: Try CBT and antidepressants. Preferred strategy for ‘mismatched’ category of illnesses. Current Psychiatry, 6(2), 101-115. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychiatry at IDEAS: Inova Digital e-ArchiveS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychiatry Articles by an authorized administrator of IDEAS: Inova Digital e-ArchiveS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CP_0207_Marcangelo.FinalREV 1/21/07 3:15 PM Page 101 Resistant somatoform symptoms: Try CBT and antidepressants Preferred strategy for ‘mismatched’ category of illnesses Michael J. Marcangelo, MD Fellow in psychosomatic medicine Department of psychiatry ® Dowden Health Media INOVA Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, VA George Washington University Washington, DC CopyrightFor personal use only Thomas Wise, MD Chairman, department of psychiatry INOVA Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, VA Professor, department of psychiatry Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD reatment-resistant somatoform disorders T are chronic (duration >1 year), can cause significant functional impairment, and respond poorly to routine care. In the somatoform category, DSM-IV-TR in- cludes diverse diagnoses such as conversion disor- der, hypochondriasis, pain disorder, and body dys- morphic disorder. But like mismatched shoes, these disorders do not fit together well—one rea- son they are often misdiagnosed and ineffectively treated. -

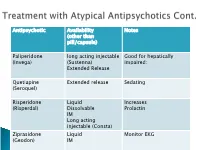

Antipsychotic Availability (Other Than Pill/Capsule) Notes Paliperidone

Antipsychotic Availability Notes (other than pill/capsule) Paliperidone long acting injectable Good for hepatically (Invega) (Sustenna) impaired; Extended Release Quetiapine Extended release Sedating (Seroquel) Risperidone Liquid Increases (Risperdal) Dissolvable Prolactin IM Long acting injectable (Consta) Ziprasidone Liquid Monitor EKG (Geodon) IM Supportive Psychotherapy Club House ACT services NAMI Vocational Rehab Nicotine counseling 1 (or more ) delusions Duration: 1 month or longer Criterion A for Schizophrenia has never been met. Functioning is not markedly impaired Behavior is not obviously odd or bizarre Features: Differential Diagnosis Prevalence: Obsessive-compulsive and ◦ lifetime 0.2 % related disorders ◦ Most frequent is persecutory Delirium • Males > females for Jealous major neurocognitive d/o type psychotic disorder due to • Function is generally better another medical condition than in schizophrenia substance-medication- • Familiar relationship with induced psychotic disorder schizophrenia and Schizophrenia & schizotypal Schizophreniform Depressive and bipolar d/o Schizoaffective Disorder Delusion types Erotomanic Grandiose Jealous Persecutory Somatic Mixed Unspecified • Substance Abuse • Dependence • Withdrawal ◦ Alcohol Divided into 2 ◦ Caffeine groups: ◦ Cannabis ◦ Hallucinogens (with separate ◦ Substance use categories for phencyclidine and other disorders hallucinogens) ◦ Substance-induced ◦ Inhalants disorders ◦ Opioids ◦ Sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics ◦ Stimulants (amphetamine-type -

Risk Factors for Early Treatment Discontinuation in Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

CLINICS 2011;66(3):387-393 DOI:10.1590/S1807-59322011000300004 CLINICAL SCIENCE Risk factors for early treatment discontinuation in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder Juliana Belo Diniz,I Dante Marino Malavazzi,I Victor Fossaluza,I,II Cristina Belotto-Silva,I Sonia Borcato,I Izabel Pimentel,I Euripedes Constantino Miguel,I Roseli Gedanke ShavittI I Department & Institute of Psychiatry, University of Sa˜ o Paulo School of Medicine Hospital das Clı´nicas, Sa˜ o Paulo, Brazil. II Mathematics and Statistics Institute, University of Sa˜ o Paulo, Sa˜ o Paulo, Brazil. INTRODUCTION: In obsessive-compulsive disorder, early treatment discontinuation can hamper the effectiveness of first-line treatments. OBJECTIVE: This study aimed to investigate the clinical correlates of early treatment discontinuation among obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. METHODS: A group of patients who stopped taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or stopped participating in cognitive behavioral therapy before completion of the first twelve weeks (total n = 41; n = 16 for cognitive behavioral therapy and n = 25 for SSRIs) were compared with a paired sample of compliant patients (n = 41). Demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained at baseline using structured clinical interviews. Chi- square and Mann-Whitney tests were used when indicated. Variables presenting a p value ,0.15 for the difference between groups were selected for inclusion in a logistic regression analysis that used an interaction model with treatment dropout as the response variable. RESULTS: Agoraphobia was only present in one (2.4%) patient who completed the twelve-week therapy, whereas it was present in six (15.0%) patients who dropped out (p = 0.044).