Unit 10 : Art and Architecture of Assam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Forgotten Saga of Rangpur's Ahoms

High Technology Letters ISSN NO : 1006-6748 The Forgotten Saga of Rangpur’s Ahoms - An Ethnographic Approach Barnali Chetia, PhD, Assistant Professor, Indian Institute of Information Technology, Vadodara, India. Department of Linguistics Abstract- Mong Dun Shun Kham, which in Assamese means xunor-xophura (casket of gold), was the name given to the Ahom kingdom by its people, the Ahoms. The advent of the Ahoms in Assam was an event of great significance for Indian history. They were an offshoot of the great Tai (Thai) or Shan race, which spreads from the eastward borders of Assam to the extreme interiors of China. Slowly they brought the whole valley under their rule. Even the Mughals were defeated and their ambitions of eastward extensions were nipped in the bud. Rangpur, currently known as Sivasagar, was that capital of the Ahom Kingdom which witnessed the most glorious period of its regime. Rangpur or present day sivasagar has many remnants from Ahom Kingdom, which ruled the state closely for six centuries. An ethnographic approach has been attempted to trace the history of indigenous culture and traditions of Rangpur's Ahoms through its remnants in the form of language, rites and rituals, religion, archaeology, and sacred sagas. Key Words- Rangpur, Ahoms, Culture, Traditions, Ethnography, Language, Indigenous I. Introduction “Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair! Nothing beside remains. Round the decay of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare, the lone and level sands stretch far away.” -P.B Shelley Rangpur or present day Sivasagar was one of the most prominent capitals of the Ahom Kingdom. -

Class-6 New 2020.CDR

Foreword I am greatly pleased to introduce the inaugural issue of “rediscovering Assam- An Endeavour of DPS Guwahati” . The need for familiarizing the students with the rich historical background, unique geographical features and varied flora and fauna of Assam had long been felt both by the teaching fraternity as well as the parent community. The text has been prepared by the teachers of Delhi Public School Guwahati with the sole aim of fulfilling this need. The book which has three parts will cater to the learning requirement of the students of classes VI, VII, VIII. I am grateful towards the teachers who have put in their best efforts to develop the contents of the text and I do hope that the students will indeed rediscover Assam in all its glory. With best wishes, Chandralekha Rawat Principal Delhi Public School Guwahati @2015 ; Delhi Public School Guwahati : “all rights reserved” Index Class - VI Sl No. Subject Page No. 1 Environmental Science 7-13 2 Geography 14-22 3 History 23-29 Class - VII Sl No. Subject Page No. 1 Environmental Science 33-39 2 Geography 40-46 3 History 47-62 Class - VIII Sl No. Subject Page No. 1 Environmental Science 65-71 2 Geography 72-82 3 History 83-96 CLASS-VI Assam, the north-eastern sentinel of the frontiers of India, is a state richly endowed with places of tourist attractions (Fig.1.1). Assam is surrounded by six of the other Seven Sister States: Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, Tripura, and Meghalaya. Assam has the second largest area after Arunachal Pradesh. -

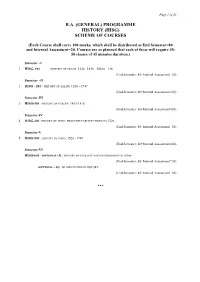

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

The Borderlands and Borders of the Indian Subcontinent, New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2018, Pp 232

Book Discussion Dilip K Chakrabarti: The Borderlands and Borders of the Indian Subcontinent, New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2018, pp 232 Understanding Indian Borderlands Dilip K Chakrabarti he Indian subcontinent shares borders with Iran, Afghanistan, the plateau of Tibet Tand Myanmar. The sub-continent’s influence extends beyond these borders, creating distinct ‘borderlands’ which are basically geographical, political, economic and religious interaction zones. It is these ‘borderlands’ which historically constitute the subcontinent’s ‘area of influence’ and underlines its civilizational role in the Asian landmass. A clear understanding of this civilizational role may be useful in strengthening India’s perception of her own geo-strategic position. Iran One may begin with Iran at the western limit of these borderland. There are two main mountain ranges in Iran : the Zagros which separates Iran from Iraq and has to its south the plain of Khuzestan giving access to south Iraq ; and the Elburz which separates the inland Iran from the Caspian belt, Turkmenistan and (to a limited extent , Azerbaijan). The Caspian shores form a well-wooded verdant belt which poses a strong contrast to the dry Iranian plateau. There are two deserts inside the Iranian plateau -- dasht-i-lut and dasht-i-kevir, which do not encourage human habitation. The population concentration of Iran is along the margins of the mountain belt and also in Khuzestan. The following facts are noteworthy. The eastern rim of Iran carries an imprint of the subcontinent. There is a ready access to Iranian Baluchistan through the Kej valley in Pakistani Baluchistan. At its eastern edge this valley leads both to lower Sindh and Kalat. -

Chiipter I Introduction

. ---- -·--··· -··-·- ------ -·-- ·----. -- ---~--- -~----------------~~---- ~-----~--~-----~-·------------· CHIIPTER I INTRODUCTION A Brief Survey of Land and People of the Area Under Study T~e present district of Kamrup, created in 1983, is. bounded by Bhutan on the north~ districts of Pragjyoti~pur and Nagaon on the east, Goalpara and Nalbari on the west and the s t LJ t e of 11 e 9 hal a y a u n t 1'1 e s u u t h . l L tl d s d n d rea of 4695.7 sq.kms., and a population of 11'106861 . Be"fore 1983, Kamrup was comprised of four present districts viz., Kamrup, Nalbari, Barpeta and ~ragjyotispur with a total 2 area of 'l863 sq.kms. and a population of 28,54,183. The density of population was 289 per sq.km. It was then boun- ded by Bhutan on the north, districts of Darrang and Nagaon on the east, district of Goalpara on the west and the state of neghalaya on the south. Lying between 26°52'40n and 92°52'2" north latitude and '10°44'30" and '12°12'20~ east longitude, the great river Brahmaputra divides it into two halves viz., South Kamrup and North Kamrup. The northern 1 statistical Handbook of Assam, Government of Assam, 1987, p.6. 2 Census, 1971·· 2 . 3 portion is about twice the area of the southern port1on . All of the rivers and streams which intersect the district arise in the hills and mountains and flow into the Brahmaputra. The principal northern tributaries are the Manas, the Barnadi and the ?agladia which rise in the Himalaya mountains- These rivers have a tendency to change their course and wander away from the former channels because of the direct push from the Himalayas. -

Magazine-2-3.Qxd (Page 2)

SUNDAY, AUGUST 30, 2015 (PAGE-3) SACRED SPACE BOOK REVIEW Upanishads Rediscovering Hinduism in the Himalayas Surinder Koul sacerdotal rites. Description about several obliterated sculptures of Source of Spirituality Albeit, the writer is professionally medical doctor, who often trav- images of Hindu Goddess and Gods , carved pillars, floral designs els to Arunachal Pradesh, the remotest part of the country and other on plinth slabs, full lotus carved on circular stone slab in Malinithan R C Kotwal Rajasthan and M.P. of present day India. places, out of her inquisitiveness and yearning to study cultural and temple premises are mentioned in minute details . Book also car- The exact numbers of the Upanishads are not clearly architectural sites in the country, yet she has produced the book as ries out various performances of worshipping that was prevalent in Upanishads means the inner or mystic teaching. The term known. Scholars differ on the total number of Upanishads as an intellectual fallow for interested people to undertake further deep main land India among the Hindus and had been practiced by the research about cultural heritage, sociological and environmental people in Arunachal Pradesh also from ages. It has identified tem- "Upanishad" is derived from Upa(Near) , ni ( down) and shad well as what constitutes an Upanishad. Some of the Upan- (to sit) i.e sitting down near. Groups of pupils sit near the aspects of earlier called NEFA now lately rechristened as Arunachal ples precincts and ruins where worshipping of Shiva Linga, worship- ishads are very ancient, but some are of recent origin. Pradesh. This region Arunachal Pradesh, had remained neglected ping of Durga as Malini still exist and on auspicious occasion devo- teacher to learn from him the secret doctrine. -

Hindutva Paper

Edinburgh Research Explorer The Power of Persuasion Citation for published version: Longkumer, A 2017, 'The Power of Persuasion: Hindutva, Christianity, and the discourse of religion and culture in Northeast India', Religion, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 203-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2016.1256845 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/0048721X.2016.1256845 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Religion Publisher Rights Statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Religion on 7/12/2016, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/0048721X.2016.1256845 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 The Power of Persuasion: Hindutva, Christianity, and the discourse of religion and culture in Northeast India.1 Abstract: The paper will examine the intersection between Sangh Parivar activities, Christianity, and indigenous religions in relation to the state of Nagaland. I will argue that the discourse of ‘religion and culture’ is used strategically by Sangh Parivar activists to assimilate disparate tribal groups and to envision a Hindu nation. -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

Download Itinerary

Starting From Rs. 14102.4 (Per Person twin sharing) PACKAGE NAME : No 11 North East Triangle PRICE INCLUDE Hotel,Only Breakfast,Activity,Sightseeing,Car On Disposal Day : 1 Guwahati - Kaziranga National Park (230 KM 4.5 Hrs) Welcome to Guwahati. Meet and be assisted by our representative at the airport/Railway Station. Transfer to Kaziranga National Park, the home of the One Horn Indian Rhinoceros. Check in at your hotel/Lodge/resort. Evening you may visit Orchid Park and the nearby Tea Plantations. Overnight stay at Kaziranga National Park. HOTEL Florican Lodge SIGHTSEEING Orchid Park Day : 2 Kaziranga National Park Early morning explore Kaziranga National Park on back of elephant. Apart from world's endangered One Horn Indian Rhinoceros, the Park sustains half the world's population of genetically pure Wild Water Buffaloes, over 1000 Wild elephants and perhaps the densest population of Royal Bengal Tiger anywhere. Kaziranga National Park is also a bird watcher's paradise and home to some 500 species of Birds. The Crested Serpent Eagle, Palla's Fishing Eagle, Greyheaded Fishing Eagle, Swamp Partridge, Bar-headed goose, whistling Teal, Bengal Florican, Storks, Herons and Pelicans are some of the species found here. We will return to the resort for breakfast. Afternoon we proceed for a jeep safari. Evening come back to the hotel. Overnight stay at Kaziranga National Park. HOTEL Florican Lodge SIGHTSEEING Elephant Safari (Kaziranga), Jeep Safari (Kaziranga) Day : 3 Kaziranga National Park– Shillong (280 Km | 6 Hrs) After breakfast drive to Shillong, also called 'Scotland of the East". Reach the majestic Umium Lake (Barapani). -

Unit 6: Religious Traditions of Assam

Assamese Culture: Syncretism and Assimilation Unit 6 UNIT 6: RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS OF ASSAM UNIT STRUCTURE 6.1 Learning Objectives 6.2 Introduction 6.3 Religious Traditions of Assam 6.4 Saivism in Assam Saiva centres in Assam Saiva literature of Assam 6.5 Saktism in Assam Centres of Sakti worship in Assam Sakti literature of Assam 6.6 Buddhism in Assam Buddhist centres in Assam Buddhist literature of Assam 6.7 Vaisnavism in Assam Vaisnava centres in Assam Vaisnava literature of Assam 6.8 Let Us Sum Up 6.9 Answer To Check Your Progress 6.10 Further Reading 6.11 Model Questions 6.1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES After going through this unit, you will be able to- know about the religious traditions in Assam and its historical past, discuss Saivism and its influence in Assam, discuss Saktism as a faith practised in Assam, describe the spread and impact on Buddhism on the general life of the people, Cultural History of Assam 95 Unit 6 Assamese Culture: Syncretism and Assimilation 6.2 INTRODUCTION Religion has a close relation with human life and man’s life-style. From the early period of human history, natural phenomena have always aroused our fear, curiosity, questions and a sense of enquiry among people. In the previous unit we have deliberated on the rich folk culture of Assam and its various aspects that have enriched the region. We have discussed the oral traditions, oral literature and the customs that have contributed to the Assamese culture and society. In this unit, we shall now discuss the religious traditions of Assam. -

Annual Report 2015-16

ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 NATIONAL CULTURE FUND Annual Report 2015-16 NATIONAL CULTURE FUND 1 P R E F A C E uring the year 2015-16, National Culture Fund (NCF) has Dunrelentingly continued its thrust on reframing & revitalizing its ongoing projects and strived towards their completion. Not only has it established new partnerships, but has also taken forward the existing relationships to a higher level. Year on Year the activities and actions of NCF have grown owing to the awareness as well as necessity to preserve and protect our heritage monuments. This Annual Report for the year 2015-16 records the efforts made by NCF to ensure accountability, effective management and rebuilding of NCF's credibility and brand image for the Government , Corporate Sector and Civil Society. The field of heritage conservation and development of the art and culture is vast and important and NCF will continue to develop and make a positive contribution to the field in the years to come. ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 4 NATIONAL CULTURE FUND ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 CONTENTSCONTENTSCONTENTS S. Details Page No. No. 1 Introduction to National Culture Fund 6 2 Management and Administration 7 3 Structure of the National Culture Fund 8 4 Activities and Highlights 2015-16 9 5 On-Going Projects 9 6 New Projects Initiated in 2015-16 10 7 Projects Completed /Ongoing 13 8 Audited Statement Of Accounts 33 NATIONAL CULTURE FUND 5 ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 1. INTRODUCTION he National Culture Fund (NCF) was set up by the Govt. of India, TDepartment of Culture (now Ministry of Culture), as a Trust under the Charitable Endowment Act, 1890 through a Gazette Notification published in the Gazette of India, 28th November, 1996. -

An Introduction to the Sattra Culture of Assam: Belief, Change in Tradition

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 12 (2): 21–47 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2018-0009 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE SATTRA CULT URE OF ASSAM: BELIEF, CHANGE IN TRADITION AND CURRENT ENTANGLEMENT BABURAM SAIKIA PhD Student Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore University of Tartu Ülikooli 16, 51003 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT In 16th-century Assam, Srimanta Sankaradeva (1449–1568) introduced a move- ment known as eka sarana nama dharma – a religion devoted to one God (Vishnu or Krishna). The focus of the movement was to introduce a new form of Vaishnava doctrine, dedicated to the reformation of society and to the abolition of practices such as animal sacrifice, goddess worship, and discrimination based on caste or religion. A new institutional order was conceptualised by Sankaradeva at that time for the betterment of human wellbeing, which was given shape by his chief dis- ciple Madhavadeva. This came to be known as Sattra, a monastery-like religious and socio-cultural institution. Several Sattras were established by the disciples of Sankaradeva following his demise. Even though all Sattras derive from the broad tradition of Sankaradeva’s ideology, there is nevertheless some theological seg- mentation among different sects, and the manner of performing rituals differs from Sattra to Sattra. In this paper, my aim is to discuss the origin and subsequent transformations of Sattra as an institution. The article will also reflect upon the implication of traditions and of the process of traditionalisation in the context of Sattra culture. I will examine the power relations in Sattras: the influence of exter- nal forces and the support of locals to the Sattra authorities.