Downloaded from Brill.Com10/02/2021 03:30:56AM Via Free Access 362 Epstein Characterises Them As Aberrations and Oddities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beginnings of English Protestantism

THE BEGINNINGS OF ENGLISH PROTESTANTISM PETER MARSHALL ALEC RYRIE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge ,UK West th Street, New York, -, USA Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, , Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on , Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town , South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Baskerville Monotype /. pt. System LATEX ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library hardback paperback Contents List of illustrations page ix Notes on contributors x List of abbreviations xi Introduction: Protestantisms and their beginnings Peter Marshall and Alec Ryrie Evangelical conversion in the reign of Henry VIII Peter Marshall The friars in the English Reformation Richard Rex Clement Armstrong and the godly commonwealth: radical religion in early Tudor England Ethan H. Shagan Counting sheep, counting shepherds: the problem of allegiance in the English Reformation Alec Ryrie Sanctified by the believing spouse: women, men and the marital yoke in the early Reformation Susan Wabuda Dissenters from a dissenting Church: the challenge of the Freewillers – Thomas Freeman Printing and the Reformation: the English exception Andrew Pettegree vii viii Contents John Day: master printer of the English Reformation John N. King Night schools, conventicles and churches: continuities and discontinuities in early Protestant ecclesiology Patrick Collinson Index Illustrations Coat of arms of Catherine Brandon, duchess of Suffolk. -

THE ICONOGRAPHY of MEXICAN FOLK RETABLOS by Gloria Kay

The iconography of Mexican folk retablos Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Giffords, Gloria Fraser, 1938- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 20:27:37 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/552047 THE ICONOGRAPHY OF MEXICAN FOLK RETABLOS by Gloria Kay Fraser Giffords A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ART In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN HISTORY OF ART In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manu script in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: Robert M. -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. Although early modern theologians and polemicists widely declared religious conformists to be shameless apostates, when we examine specific cases in context it becomes apparent that most individuals found ways to positively rationalize and justify their respective actions. This fraught history continued to have long-term effects on England’s religious, political, and intellectual culture. -

The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art

Dominican Scholar Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Liberal Arts and Education | Graduate Theses Student Scholarship May 2019 The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art Maura Wilson Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2019.HUM.06 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Wilson, Maura, "The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art" (2019). Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Theses. 6. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2019.HUM.06 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberal Arts and Education | Graduate Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This thesis, written under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor and approved by the department chair, has been presented to and accepted by the Master of Arts in Humanities Program in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts in Humanities. An electronic copy of of the original signature page is kept on file with the Archbishop Alemany Library. Maura Wilson Candidate Joan Baranow, PhD Program Chair Joan Baranow, PhD First Reader Sandra Chin, MA Second Reader This master's thesis is available at Dominican Scholar: https://scholar.dominican.edu/humanities- masters-theses/6 i The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art By Maura Wilson This thesis, written under the direction of the candidate’s thesis advisor and approved by the program chair, has been presented to an accepted by the Department of Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Humanities Dominican University of California San Rafael, CA May 2019 ii iii Copyright © Maura Wilson 2019. -

Part Two Patrons and Printers

PART TWO PATRONS AND PRINTERS CHAPTER VI PATRONAGE The Significance of Dedications The Elizabethan period was a watershed in the history of literary patronage. The printing press had provided a means for easier publication, distribution and availability of books; and therefore a great patron, the public, was accessible to all authors who managed to get Into print. In previous times there were too many discourage- ments and hardships to be borne so that writing attracted only the dedicated and clearly talented writer. In addition, generous patrons were not at all plentiful and most authors had to be engaged in other occupations to make a living. In the last half of the sixteenth century, a far-reaching change is easily discernible. By that time there were more writers than there were patrons, and a noticeable change occurred In the relationship between patron and protge'. In- stead of a writer quietly producing a piece of literature for his patron's circle of friends, as he would have done in medieval times, he was now merely one of a crowd of unattached suitors clamouring for the favours and benefits of the rich. Only a fortunate few were able to find a patron generous enough to enable them to live by their pen. 1 Most had to work at other vocations and/or cultivate the patronage of the public and the publishers. •The fact that only a small number of persons had more than a few works dedicated to them indicates the difficulty in finding a beneficent patron. An examination of 568 dedications of religious works reveals that only ten &catees received more than ten dedications and only twelve received between four and nine. -

The Opening of the Atlantic World: England's

THE OPENING OF THE ATLANTIC WORLD: ENGLAND’S TRANSATLANTIC INTERESTS DURING THE REIGN OF HENRY VIII By LYDIA TOWNS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington May, 2019 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Imre Demhardt, Supervising Professor John Garrigus Kathryne Beebe Alan Gallay ABSTRACT THE OPENING OF THE ATLANTIC WORLD: ENGLAND’S TRANSATLANTIC INTERESTS DURING THE REIGN OF HENRY VIII Lydia Towns, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2019 Supervising Professor: Imre Demhardt This dissertation explores the birth of the English Atlantic by looking at English activities and discussions of the Atlantic world from roughly 1481-1560. Rather than being disinterested in exploration during the reign of Henry VIII, this dissertation proves that the English were aware of what was happening in the Atlantic world through the transnational flow of information, imagined the potentials of the New World for both trade and colonization, and actively participated in the opening of transatlantic trade through transnational networks. To do this, the entirety of the Atlantic, all four continents, are considered and the English activity there analyzed. This dissertation uses a variety of methods, examining cartographic and literary interpretations and representations of the New World, familial ties, merchant networks, voyages of exploration and political and diplomatic material to explore my subject across the social strata of England, giving equal weight to common merchants’ and scholars’ perceptions of the Atlantic as I do to Henry VIII’s court. Through these varied methods, this dissertation proves that the creation of the British Atlantic was not state sponsored, like the Spanish Atlantic, but a transnational space inhabited and expanded by merchants, adventurers and the scholars who created imagined spaces for the English. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Icons and Western Art

Icons and Western art Eastern and Western religious art. Developments in Western painting 1. Symbolic / idealistic stage Eastern Orthodox icons and early Western painting (medieval) tries to express symbolically “what we know” about God and the world: ideas, teachings, etc. Such art expresses a general perspective of things: a symbolic point of view (“God’s eye”) of how things are (Ortega y Gasset). Eastern Orthodox art remained at the “symbolic” stage, and Eastern secular painting developed at a very late stage, if at all. In the West, such symbolic or general point of view was maintained until the Middle Ages (mid-13th c.). Examples are early Franciscan art, e.g., Bardi’s Dossal of Francis or the San Damiano crucifix. 2. Realistic / illusionistic stage Realistic or illusionistic art tries to represent “what we see” of things, rather than what we know about them. It seems to develop whenever art is used for entertainment (secular). However, in the West it takes over religious painting as well. This sort of art pays particular attention to various aspects of seeing or optical science: three-dimensional space, linear perspective, natural lighting, realistic portrayal of detail, etc. Realistic / illusionistic art represents the individual perspective or individual point of view: not what we know about things (general perspective) but what one sees of things (Ortega y Gasset). Western art of this type stresses material, rather than spiritual beauty, and contains many naturalistic details and sensual imagery. ART AND RELIGION, BY O. BYCHKOV 17 3. Experimental stages in Western painting In the 1800’s the tendency to paint “what we see,” or realism, begins to give way to the tendency to paint “how we see.” At first, Western painters tried to paint their “impressions” of reality (impressionism). -

The Account Book of a Marian Bookseller, 1553-4

THE ACCOUNT BOOK OF A MARIAN BOOKSELLER, 1553-4 JOHN N. KING MS. EGERTON 2974, fois. 67-8, preserves in fragmentary form accounts from the day-book of a London stationer who was active during the brief interval between the death on 6 July 1553 of Edward VI, whose regents allowed unprecedented liberty to Protestant authors, printers, publishers, and booksellers, and the reimposition of statutory restraints on publication by the government of Queen Mary. The entries for dates, titles, quantities, paper, and prices make it clear that the leaves come from a bookseller's ledger book. Their record of the articles sold each day at the stationer's shop provides a unique view of the London book trade at an unusually turbulent point in the history of English publishing. Before they came into the holdings of the British Museum, the two paper leaves (fig. i) were removed from a copy of William Alley's The poore mans librarie (1565) that belonged to Thomas Sharpe of Coventry. They are described as having been pasted at the end ofthe volume *as a fly leaf, and after their removal, William Hamper enclosed them as a gift in a letter of 17 March 1810 to the Revd Thomas Frognall Dibdin (MS. Egerton 2974, fois. 62, 64). The leaves are unevenly trimmed, but each measures approximately 376 x 145 mm overall. Because of their format they are now bound separately, but they formed part of a group of letters to Dibdin purchased loose and later bound in the Museum, so they belong together with MS. -

Iconography of Jesus Christ in Nubian Painting 242 MAŁGORZATA MARTENS-CZARNECKA

INSTITUT DES CULTURES MÉDITERRANÉENNES ET ORIENTALES DE L’ACADÉMIE POLONAISE DES SCIENCES ÉTUDES et TRAVAUX XXV 2012 MAŁGORZATA MARTENS-CZARNECKA Iconography of Jesus Christ in Nubian Painting 242 MAŁGORZATA MARTENS-CZARNECKA In religious art the image of Christ was one of the key elements which inspired the faithful to prayer and contemplation. Pictured as the Incarnation of Logos, the Son of God, the Child born unto Mary, the fi gure of Christ embodied the most important dogma of Christianity.1 Depicted in art, Christ represents the hypostasis of the Word made man – the Logos in human form.2 Christ the Logos was made man (κατά τόν ανθρώπινον χαρακτήρα). God incarnate, man born of Mary, as dictated by canon 82 of the Synod In Trullo in Constan- tinople (AD 692), was to be depicted only in human form, replacing symbols (the lamb).3 From the moment of incarnation, the image of Christ became easily perceptible to the human eye, and hence readily defi ned in shape and colour.4 Artists painting representations of Christ drew inspiration from the many descriptions recorded in the apocrypha: ... and with him another, whose countenance resembled that of man. His countenance was full of grace, like that of one of the holy angels (1 Enoch 46:1). For humankind Christ was the most essential link between the seen and the unseen, between heaven and Earth;5 the link between God and the men sent by God (John 1:6; 3:17; 5:22-24), through whom God endows the world with all that is good. He is the mediator to whom the faithful, often through the intercession of the Virgin, make supplication and prayer – if you ask the Father anything in my name, he will give it to you (John 16:23; 14:11-14; 15:16). -

Jesus Christ's Sufferings and Death in the Iconography of the East and the West

Скрижали, 4, 2012, с. 122-138 V.V.Akimov Jesus Christ's sufferings and death in the iconography of the East and the West The image of God sufferings, Jesus Christ crucifixion has received such wide spreading in the Christian world that is hardly possible to count up total of the similar monuments created throughout last one and a half thousand of years. The crucifixion has got a habitual symbol of Christianity and various types of the Crucifix became a distinctive feature of some Christian faiths. From time to time modern Christians, looking at the Cross with crucified Jesus Christ, don’t think of the tragedy of Christ’s death and the joy of His resurrection but whether the given Crucifix is «their own» or «another's». Meanwhile, the iconography of the Crucifix as far as the iconography of God’s Mother can testify to a generality of Christian tradition of the East and the West. There are much more general lines than differences between them. The evangelical narration of God sufferings and the history of Crucifix iconography formation, both of these, testify to the unity of east and western tradition of the image of the Crucifixion. Traditions of the East and the West had one source and were in constant interaction. Considering the Crucifix iconography of the East and the West in a context of the evangelical narration and in a historical context testifies to the unity of these traditions and leads not to dissociation, conflicts and mutual recriminations, but gives an impulse to search of the lost unity. -

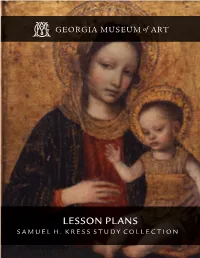

Lesson Plans Samuel H

LESSON PLANS SAMUEL H. KRESS STUDY COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Lesson Plans, Grades K–12 3 What’s the Subject? Iconography 4 Studio Art Activity: Contemporary Icons 7 What’s the Subject? Mothers and Children 11 Studio Art Activity: Designing Women (and Their Children) 12 What’s the Subject? Images as Stories 15 Studio Art Activity Grades K–12: Getting the Whole Story 16 How’s That Made? Multi-Panel Altarpieces 19 Studio Art Activity Grades K–12: The Secret Lives of Renaissance Altarpieces 20 How’s That Made? Tempera and Oil Paint 24 Studio Art Activity: Paint Wars—Tempera vs. Oil 26 How’s That Made? Linear Perspective 30 Studio Art Activity: 2-D Art from a 3-D World 31 Worksheets35 LESSON PLANS, GRADES K–12 EXPERIENCE AND LEARNING WITH THE KRESS COLLECTION These lesson plans are a supplement to the Kress Teaching Packet. In the teaching packet, which is our primary instructional handbook, you will find images, information and looking guides for each of the 12 works of art in the Kress Collection at the Georgia Museum of Art, as well as an overview of Renaissance history. Educators are strongly encouraged to visit the museum with their students to experience our Kress Collection firsthand. The teaching packet and lesson plans offer a well-rounded understanding of Renaissance art; however, no reproduction can fully convey the beauty of an individual’s interaction with these works of art in the galleries. To organize a field trip, please contact the museum’s education department at 706.542.8863. WHAT’S THE SUBJECT? There are many interesting subjects to explore within Renaissance art.