Assessing Factors Influencing a Possible South

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Rev Cop16) on Conservation of and Trade in Tiger

SC65 Doc. 38 Annex 1 REVIEW OF IMPLEMENTATION OF RESOLUTION CONF. 12.5 (REV. COP16) ON CONSERVATION OF AND TRADE IN TIGERS AND OTHER APPENDIX-I ASIAN BIG CAT SPECIES* Report to the CITES Secretariat for the 65th meeting of the Standing Committee Kristin Nowell, CAT and IUCN Cat Specialist Group and Natalia Pervushina, TRAFFIC With additional support from WWF Table of Contents Section Page Executive Summary 2 1. Introduction 8 2. Methods 11 3. Conservation status of Asian big cats 12 4. Seizure records for Asian big cats 13 4.1. Seizures – government reports 13 4.1.1. International trade databases 13 4.1.2. Party reports to CITES 18 4.1.3. Interpol Operation Prey 19 4.2. Seizures – range State and NGO databases 20 4.2.1. Tigers 21 4.2.2. Snow leopards 25 4.2.3. Leopards 26 4.2.4. Other species 27 5. Implementation of CITES recommendations: best practices and 28 continuing challenges 5.1. Legislative and regulatory measures 28 5.2. National law enforcement 37 5.3. International cooperation for enforcement and conservation 44 5.4. Recording, availability and analysis of information 46 5.5. Demand reduction, education, and awareness 48 5.6. Prevention of illegal trade in parts and derivatives from captive 53 facilities 5.7. Management of government and privately-held stocks of parts and 56 derivatives 5.8. Recent meetings relevant to Asian big cat conservation and trade 60 control 6. Recommendations 62 References 65 * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Energy in China: Coping with Increasing Demand

FOI-R--1435--SE November 2004 FOI ISSN 1650-1942 SWEDISH DEFENCE RESEARCH AGENCY User report Kristina Sandklef Energy in China: Coping with increasing demand Defence Analysis SE-172 90 Stockholm FOI-R--1435--SE November 2004 ISSN 1650-1942 User report Kristina Sandklef Energy in China: Coping with increasing demand Defence Analysis SE-172 90 Stockholm SWEDISH DEFENCE RESEARCH AGENCY FOI-R--1435--SE Defence Analysis November 2004 SE-172 90 Stockholm ISSN 1650-1942 User report Kristina Sandklef Energy in China: Coping with increasing demand Issuing organization Report number, ISRN Report type FOI – Swedish Defence Research Agency FOI-R--1435--SE User report Defence Analysis Research area code SE-172 90 Stockholm 1. Security, safety and vulnerability Month year Project no. November 2004 A 1104 Sub area code 11 Policy Support to the Government (Defence) Sub area code 2 Author/s (editor/s) Project manager Kristina Sandklef Ingolf Kiesow Approved by Maria Hedvall Sponsoring agency Department of Defense Scientifically and technically responsible Report title Energy in China: Coping with increasing demand Abstract (not more than 200 words) Sustaining the increasing energy consumption is crucial to future economic growth in China. This report focuses on the current and future situation of energy production and consumption in China and how China is coping with its increasing domestic energy demand. Today, coal is the most important energy resource, followed by oil and hydropower. Most energy resources are located in the inland, whereas the main demand for energy is in the coastal areas, which makes transportation and transmission of energy vital. The industrial sector is the main driver of the energy consumption in China, but the transport sector and the residential sector will increase their share of consumption by 2020. -

China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States

Order Code RL32688 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Updated April 4, 2006 Bruce Vaughn (Coordinator) Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Wayne M. Morrison Specialist in International Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Summary Southeast Asia has been considered by some to be a region of relatively low priority in U.S. foreign and security policy. The war against terror has changed that and brought renewed U.S. attention to Southeast Asia, especially to countries afflicted by Islamic radicalism. To some, this renewed focus, driven by the war against terror, has come at the expense of attention to other key regional issues such as China’s rapidly expanding engagement with the region. Some fear that rising Chinese influence in Southeast Asia has come at the expense of U.S. ties with the region, while others view Beijing’s increasing regional influence as largely a natural consequence of China’s economic dynamism. China’s developing relationship with Southeast Asia is undergoing a significant shift. This will likely have implications for United States’ interests in the region. While the United States has been focused on Iraq and Afghanistan, China has been evolving its external engagement with its neighbors, particularly in Southeast Asia. In the 1990s, China was perceived as a threat to its Southeast Asian neighbors in part due to its conflicting territorial claims over the South China Sea and past support of communist insurgency. -

Dramatic Decline of Wild South China Tigers Panthera Tigris Amoyensis: field Survey of Priority Tiger Reserves

Oryx Vol 38 No 1 January 2004 Dramatic decline of wild South China tigers Panthera tigris amoyensis: field survey of priority tiger reserves Ronald Tilson, Hu Defu, Jeff Muntifering and Philip J. Nyhus Abstract This paper describes results of a Sino- tree farms and other habitat conversion is common, and American field survey seeking evidence of South China people and their livestock dominate these fragments. While tigers Panthera tigris amoyensis in the wild. In 2001 and our survey may not have been exhaustive, and there may 2002 field surveys were conducted in eight reserves in be a single tiger or a few isolated tigers still remaining at five provinces identified by government authorities as sites we missed, our results strongly indicate that no habitat most likely to contain tigers. The surveys evaluated remaining viable populations of South China tigers occur and documented evidence for the presence of tigers, tiger within its historical range. We conclude that continued prey and habitat disturbance. Approximately 290 km of field eCorts are needed to ascertain whether any wild mountain trails were evaluated. Infrared remote cameras tigers may yet persist, concurrent with the need to con- set up in two reserves captured 400 trap days of data. sider options for the eventual recovery and restoration Thirty formal and numerous informal interviews were of wild tiger populations from existing captive populations. conducted with villagers to document wildlife knowledge, livestock management practices, and local land and Keywords Extinction, Panthera tigris amoyensis, resource use. We found no evidence of wild South China restoration, South China tiger. tigers, few prey species, and no livestock depredation by tigers reported in the last 10 years. -

Sumatran Tiger

[ABCDE] Volume 1, Issue 7 Nov. 6, 2001 CURRICULUM GUIDE: TIGERS e r I n E d u c a p a p t i o w s n P N e r o t g s r a P o m n t o g i n h s T a h e W C e u h r T r i f c u O l u e r m o C A t e T h h T e t C A o r m KLMNO e u l O u An Integrated Curriculum c f i r Resource Program T r h u e C W e a h s T h i n g t o n P m o a s r t g N o r e P w s n p o a i p t a e c r u I d n E ASSOCIATED PRESS PHOTO IN THIS ISSUE Word Study Tiger Resources Wild Vocabulary 2 4 7 A look at extinction Tigers in Print Academic Content 3 5 Endangered Species 8 Standards © 2001 The Washington Post Company An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program KLMNO Volume 1, Issue 7 Nov. 6, 2001 Sumatran Tiger Tiger Resources KidsPost Article: "Earning His Stripes” On the Web and in Print ON THE WEB http://www.fonz.org/animals/tigertiger/tiger- Lesson: Investigating rare and endangered animals cubpr1.htm Level: Intermediate Friends of the National Zoo Subjects: Science See pictures and learn about Sumatran tigers at the zoo. Related Activity: Geography, English, Language Arts www.5tigers.org Procedure 5 Tigers: The Tiger Information Center Dedicated to providing an international forum focusing Read and Discuss on the preservation of wild tigers across Asia and in Read the KidsPost article. -

South China Tiger Conservation Strategy

South China Tiger Conservation Strategy Petri Viljoen Objective The South China Tiger Conservation Strategy aims to establish genetically viable, free-ranging South China tigers in suitable, newly created protected areas in south- eastern China. Background The South China Tiger ( Panthera tigris amoyensis ), also known as the Chinese Tiger, is the most endangered of the remaining living tiger subspecies (IUCN 2009). It is estimated that a small number (10-20) of free-ranging South China tigers could still be present, although no recent sightings of this tiger subspecies in its natural range have been reported. The captive population, all in Chinese zoos with the exception of 14 individuals currently in South Africa, number approximately 60 (Traylor-Holzer 1998; IUCN 2009). The South China Tiger is considered to be critically endangered (IUCN 2009) and precariously close to extinction (Tilson et al. 1997; Tilson et al. 2004). Herrington (1987) considered the South China Tiger to be a relic population of the "stem" tiger, possibly occurring close to the area of the species’ origin. Luo et al. (2004, in IUCN 2009) suggested that the centre of the original tiger radiation was most likely the southern China/northern Indochina region. Save China’s Tigers (SCT) is a UK, US, China and Hong Kong based charitable foundation. SCT’s specific mission is to save the South China Tiger from extinction and recreate a viable population of free-ranging South China Tigers in protected reserves in their former range. To achieve this objective SCT aims to assist with the development of captive breeding and reintroduction of South China Tigers in China. -

Regional Inequality in China's Health Care Expenditures

HEALTH ECONOMICS Health Econ. 18: S137–S146 (2009) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/hec.1511 REGIONAL INEQUALITY IN CHINA’S HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURES WIN LIN CHOUa,Ã and ZIJUN WANGb aDepartment of Economics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong and National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan bPrivate Enterprise Research Center, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA SUMMARY This paper has two parts. The first part examines the regional health expenditure inequality in China by testing two hypotheses on health expenditure convergence. Cross-section regressions and cluster analysis are used to study the health expenditure convergence and to identify convergence clusters. We find no single nationwide convergence, only convergence by cluster. In the second part of the paper, we investigate the long-run relationship between health expenditure inequality, income inequality, and provincial government budget deficits (BD) by using new panel cointegration tests with health expenditure data in China’s urban and rural areas. We find that the income inequality and real provincial government BD are useful in explaining the disparity in health expenditure prevailing between urban and rural areas. In order to reduce health-spending inequality, one long-run policy suggestion from our findings is for the government to implement more rapid economic development and stronger financing schemes in poorer rural areas. Copyright r 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. JEL classification: C2; C3; I10 KEY WORDS: health expenditure inequality; income inequality; government budget deficits; convergence test; panel cointegration test 1. INTRODUCTION An important feature of China’s economic reforms which began in 1978 is the dramatic change in its health system from a centrally planned system to a market-based one (Ma et al., 2008). -

HIDDEN in PLAIN SIGHT China's Clandestine Tiger Trade ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTENTS

HIDDEN IN PLAIN SIGHT China's Clandestine Tiger Trade ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTENTS This report was written by Environmental Investigation Agency. 1 EIA would like to thank the Rufford Foundation, SUMMARY the David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation, Ernest Kleinwort Charitable Trust and Save Wild Tigers for their support in making this work possible. 3 INTRODUCTION Special thanks to our colleagues “on the frontline” in tiger range countries for their information, 5 advice and inspiration. LEGAL CONTEXT ® EIA uses IBM i2 intelligence analysis software. 6 INVESTIGATION FINDINGS Report design by: www.designsolutions.me.uk 12 TIGER FARMING February 2013 13 PREVIOUS EXPOSÉS 17 STIMULATING POACHING OF WILD ASIAN BIG CATS 20 MIXED MESSAGES 24 SOUTH-EAST ASIA TIGER FARMS 25 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 26 APPENDICES 1) TABLE OF LAWS AND REGULATIONS RELATING TO TIGERS IN CHINA 2) TIGER FARMING TIMELINE ENVIRONMENTAL INVESTIGATION AGENCY (EIA) 62/63 Upper Street, London N1 0NY, UK Tel: +44 (0) 20 7354 7960 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7354 7961 email: [email protected] www.eia-international.org EIA US P.O.Box 53343 Washington DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 483 6621 Fax: +1 202 986 8626 email: [email protected] www.eia-global.org Front cover image © Robin Hamilton All images © EIA unless otherwise specified © Michael Vickers/www.tigersintheforest.co.uk SUMMARY Undercover investigations and a review of available Chinese laws have revealed that while China banned tiger bone trade for medicinal uses in 1993, it has encouraged the growth of the captive-breeding of tigers to supply a quietly expanding legal domestic trade in tiger skins. -

Dramatic Decline of Wild South China Tigers Panthera Tigris Amoyensis: Field Survey of Priority Tiger Reserves

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2004 Dramatic decline of wild South China tigers Panthera tigris amoyensis: field survey of priority tiger reserves Ronald Tilson Hu Defu Jeff Muntifering Philip J. Nyhus Colby College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tilson, Ronald; Defu, Hu; Muntifering, Jeff; and Nyhus, Philip J., "Dramatic decline of wild South China tigers Panthera tigris amoyensis: field survey of priority tiger reserves" (2004). Faculty Scholarship. 10. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/faculty_scholarship/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Oryx Vol 38 No 1 January 2004 Dramatic decline of wild South China tigers Panthera tigris amoyensis: field survey of priority tiger reserves Ronald Tilson, Hu Defu, Jeff Muntifering and Philip J. Nyhus Abstract This paper describes results of a Sino- tree farms and other habitat conversion is common, and American field survey seeking evidence of South China people and their livestock dominate these fragments. While tigers Panthera tigris amoyensis in the wild. In 2001 and our survey may not have been exhaustive, and there may 2002 field surveys were conducted in eight reserves in be a single tiger or a few isolated tigers still remaining at five provinces identified by government authorities as sites we missed, our results strongly indicate that no habitat most likely to contain tigers. -

Cats on the 2009 Red List of Threatened Species

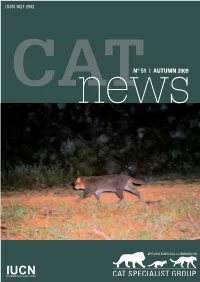

ISSN 1027-2992 CATnewsN° 51 | AUTUMN 2009 01 IUCNThe WorldCATnews Conservation 51Union Autumn 2009 news from around the world KRISTIN NOWELL1 Cats on the 2009 Red List of Threatened Species The IUCN Red List is the most authoritative lists participating in the assessment pro- global index to biodiversity status and is the cess. Distribution maps were updated and flagship product of the IUCN Species Survi- for the first time are being included on the val Commission and its supporting partners. Red List website (www.iucnredlist.org). Tex- As part of a recent multi-year effort to re- tual species accounts were also completely assess all mammalian species, the family re-written. A number of subspecies have Felidae was comprehensively re-evaluated been included, although a comprehensive in 2007-2008. A workshop was held at the evaluation was not possible (Nowell et al Oxford Felid Biology and Conservation Con- 2007). The 2008 Red List was launched at The fishing cat is one of the two species ference (Nowell et al. 2007), and follow-up IUCN’s World Conservation Congress in Bar- that had to be uplisted to Endangered by email with others led to over 70 specia- celona, Spain, and since then small changes (Photo A. Sliwa). Table 1. Felid species on the 2009 Red List. CATEGORY Common name Scientific name Criteria CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus C2a(i) ENDANGERED (EN) Andean cat Leopardus jacobita C2a(i) Tiger Panthera tigris A2bcd, A4bcd, C1, C2a(i) Snow leopard Panthera uncia C1 Borneo bay cat Pardofelis badia C1 Flat-headed -

Chinese Tourists Shopping Behaviour in New Zealand: the Case of Health

CHINESE TOURISTS SHOPPING BEHAVIOUR IN NEW ZEALAND: THE CASE OF HEALTH AND BEAUTY PRODUCTS A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Commerce in Marketing Department of Management, Marketing, and Entrepreneurship Edward Paul Commons University of Canterbury June 2018 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Without doubt, this has been one of the toughest challenges that I have completed in my life. I would not have been able to achieve this without the ongoing support and guidance from several people, who have played their part in making this thesis possible. First, I would like to thank my supervisors, Associate Professor Girish Prayag and Dr Chris Chen. This project would not have been achievable without your support, guidance and belief in me that I could complete this. So, THANK YOU! To the MCom classes of 2016/17, this has been a journey that we have shared together. The constant support and encouragement that we have given each other has always been a great morale booster. Not to mention the BYO’s and other social occasions that we have enjoyed. Good luck with your future endeavours and I look forward to staying in touch and crossing paths on our future journeys. I would also like to extend my warmest of appreciation to those people close to me, my family and friends. To Henry and Thomas, cheers for everything that you have done the past few years to ensure I was getting my full share of laughs and enjoying life outside of my studies. Thanks to my partner Anita, for your constant encouragement, patience, and voluntary tasks that you have happily undertaken to make sure that my wellbeing and health remained intact. -

An Assessment of South China Tiger Reintroduction Potential in Hupingshan and Houhe National Nature Reserves, China ⇑ Yiyuan Qin A,B, Philip J

Biological Conservation 182 (2015) 72–86 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon An assessment of South China tiger reintroduction potential in Hupingshan and Houhe National Nature Reserves, China ⇑ Yiyuan Qin a,b, Philip J. Nyhus a, , Courtney L. Larson a,g, Charles J.W. Carroll a,g, Jeff Muntifering c, Thomas D. Dahmer d, Lu Jun e, Ronald L. Tilson f a Environmental Studies Program, Colby College, Waterville, ME 04901, USA b Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, New Haven, CT, USA c Department of Conservation, Minnesota Zoo, 13000 Zoo Blvd., Apple Valley, MN 55124, USA d Ecosystems, Ltd., Unit B13, 12/F Block 2, Yautong Ind. City, 17 KoFai Road, Yau Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong e National Wildlife Research and Development Center, State Forestry Administration, People’s Republic of China f Minnesota Zoo Foundation, 13000 Zoo Blvd., Apple Valley, MN 55124, USA g Graduate Degree Program in Ecology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA article info abstract Article history: Human-caused biodiversity loss is a global problem, large carnivores are particularly threatened, and the Received 11 June 2014 tiger (Panthera tigris) is among the world’s most endangered large carnivores. The South China tiger Received in revised form 20 October 2014 (Panthera tigris amoyensis) is the most critically endangered tiger subspecies and is considered function- Accepted 28 October 2014 ally extinct in the wild. The government of China has expressed its intent to reintroduce a small popula- Available online 12 December 2014 tion of South China tigers into a portion of their historic range as part of a larger goal to recover wild tiger populations in China.