Grace in Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signs of the Times for 1880

The Signs of the Times. "Behold, I come quickly, and my reward is with me, to give every man according as his work shall be." Rev. 22 :12. VOLUME 6. OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA, FIFTH-DAY, MARCH 11, 1880. NUMBER 10. THE SIGNS OF THE TIMES. stowed upon them by their senseless gods. God the magicians. Tho frogs died, and were then ISSUED WEEKLY BY THE would glorify his own name, that other nations gathered together in heaps. Here the king and might hear of his power and tremble at his mighty all Egypt had evidence which their vain philoso- Pacific Seventh-day Adventist Publishing Association. acts, and that his people might be led to fully turn phy could not dispose of, that this work was not (For terms, etc., see last page.] from their idolatry to render to him pure worship. accomplished by magic, but was a judgment from Obedient to the command of God, Moses and the God of Heaven. GOD'S ANVIL. Aaron again entered the lordly halls of the king When the king was relieved of his immediate of Egypt. There, surrounded by the massive and distress, he again stubbornly refused to let Israel Panes furnace heat within me quivers, richly sculptured columns, and the gorgeousness go. Aaron, at the command of God stretched out God's breath upon the flame doth blow, And all my heart in anguish shivers, of rich hangings and adornments of silver and his hand and caused the dust of the earth to And trembles at the fiery glow; gold, and gems, before the monarch of the most become lice throughout all the land of Egypt. -

Benjamin Franklin

(Click Here for Index) A BOOK OF GEMS, CHOICE SELECTIONS FROM THE WRITINGS OF BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, ARRANGED BY J. A. HEADINGTON, —AND— JOSEPH FRANKLIN, — § — GOSPEL ADVOCATE COMPANY Nashville, Tennessee 1960 Copyrighted by JOHN BURNS. Stereotyped by ST. Louis TYPE FOUNDRY. iii INDEX TO SUBJECTS. (Click on title of article for text) A. Campbell's Successors and Critics .............................. 241 A Choir ..................................................... 230 A Happy Meeting ............................................. 260 A Hard Question for Preachers ................................... 458 A Higher Morality Required ...................................... 24 A Mighty Good Foundation ...................................... 457 A Mother's Grave ............................................. 140 A Phalanx of Young Men ....................................... 393 A Suggestion. ................................................. 99 A Working Ministry ............................................ 130 Activity In the Ministry ......................................... 453 Adhering to the Bible ........................................... 207 Affirmative Gospel ............................................ 428 All Things Common ............................................. 94 Annihilation—Future Punishment. ................................. 100 Anointing with Oil ............................................. 396 Apology for Creeds ............................................ 120 Authority of a Single Congregation ............................... -

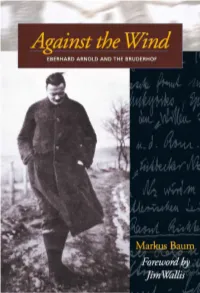

Against the Wind E B E R H a R D a R N O L D a N D T H E B R U D E R H O F

Against the Wind E B E R H A R D A R N O L D A N D T H E B R U D E R H O F Markus Baum Foreword by Jim Wallis Original Title: Stein des Anstosses: Eberhard Arnold 1883–1935 / Markus Baum ©1996 Markus Baum Translated by Eileen Robertshaw Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com Copyright © 2015, 1998 by Plough Publishing House All rights reserved Print ISBN: 978-0-87486-953-8 Epub ISBN: 978-0-87486-757-2 Mobi ISBN: 978-0-87486-758-9 Pdf ISBN: 978-0-87486-759-6 The photographs on pages 95, 96, and 98 have been reprinted by permission of Archiv der deutschen Jugendbewegung, Burg Ludwigstein. The photographs on pages 80 and 217 have been reprinted by permission of Archive Photos, New York. Contents Contents—iv Foreword—ix Preface—xi CHAPTER ONE 1 Origins—1 Parental Influence—2 Teenage Antics—4 A Disappointing Confirmation—5 Diversions—6 Decisive Weeks—6 Dedication—7 Initial Consequences—8 A Widening Rift—9 Missionary Zeal—10 The Salvation Army—10 Introduction to the Anabaptists—12 Time Out—13 CHAPTER TWO 14 Without Conviction—14 The Student Christian Movement—14 Halle—16 The Silesian Seminary—18 Growing Responsibility in the SCM—18 Bernhard Kühn and the EvangelicalAlliance Magazine—20 At First Sight—21 Against the Wind Harmony from the Outset—23 Courtship and Engagement—24 CHAPTER THREE 25 Love Letters—25 The Issue of Baptism—26 Breaking with the State Church—29 Exasperated Parents—30 Separation—31 Fundamental Disagreements among SCM Leaders—32 The Pentecostal Movement Begins—33 -

The Mid-America Adventist Outlook for 1987

July, 1987 Mid-America Union Conference of Seventh-day Adventists "For as the lightning cometh out of the east, and shineth even unto the west; so shall ---2';also the coming of the Son of man be." Matthew 24:27 ,r4 * The President's Outlook * that God has raised up the Adventist A Unique Pastor Church to help prepare people for the LOOK Second Coming of Christ. Official organ of the Mid-America Union Conference of and Church Too many of our churches today, it Seventh-day Adventists, P.O. Box 6128 (8550 Pioneers seems to me, have lost a sense of Blvd.), Lincoln, NE 68506. (402) 483-4451. Adventism's mission. There is a great Editor James L. Fly tendency to get overinvolved in the social Assistant Editor Shirley B. Engel issues of the day which diverts us from our Typesetter Cheri Winters central mission of preparing people for the Printer Christian Record Braille Foundation earth's final harvest (Revelation 14:14-16). Change of address: Give your new address with zip code That's why my visit to the Windom and include your name and old address as it appeared on church refreshed me so much. Here is a previous issues. (If possible clip your name and address body of believers who clearly understand from an old OUTLOOK.) where they are going and have a pastor who knows how to lead them there. I' i= Mid-America Union I was particularly impressed that morning = when Pastor Jim Anderson baptized —=7 Angeline Van Ort. He had Sister Van Ort face the congregation with him and then he Mid-America Union Directory President J 0. -

Hinojosa Book4cd W.Pdf (865.3Kb)

Literature, Religion, and Postsecular Studies LORI BRANCH, SERIES EDITOR All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. PURITANISM and MODERNIST NOVELS From Moral Character to the Ethical Self Lynne W. Hinojosa THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PREss • COLUMBUS All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. Copyright © 2015 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hinojosa, Lynne W., 1966– Puritanism and modernist novels : from moral character to the ethical self / Lynne W. Hinojosa. pages cm. — (Literature, religion, & postsecular studies) Includes bibliographical ref- erences and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1273-8 (hardback) — ISBN 978-0-8142-9378-2 (cd) 1. Modernism (Literature)—Great Britain. 2. English fiction—History and criticism. 3. English fiction—Irish authors—History and criticism. 4. Puritan movements in literature. 5. Christianity and literature. I. Title. PR478.M6H56 2015 823'.91209112—dc23 2014027044 Cover design by Mary Ann Smith Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Sabon Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. For Mom and Dad Victor Miriam and Monica All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. -

24 Hours Leader Guide

24 Hours That Changed the World Book 24 Hours That Changed the World Experience the final day in the life of Jesus Christ. 978-0-687-46555-2 Reflections 24 Hours That Changed the World: 40 Days of Reflection Commit to 40 days of reflection based on Jesus’ final day. 978-1-426-70031-6 DVD with Leader Guide 24 Hours That Changed the World: Video Journey Walk with Adam Hamilton in Jesus’ footsteps on the final day. 978-0-687-65970-8 Visit www.AdamHamilton.AbingdonPress.com for more information. Also by Adam Hamilton Enough Seeing Gray in a World of Black and White Christianity’s Family Tree Selling Swimsuits in the Arctic Christianity and World Religions Confronting the Controversies Making Love Last a Lifetime Unleashing the Word Leading Beyond the Walls ADAM HAMILTON 24 Hours That Changed the World L EADER G UIDE by MARK PRICE Abingdon Press Nashville 24 HOURS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD: LEADER GUIDE Copyright © 2009 by Abingdon Press. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to Abingdon Press, 201 Eighth Avenue South, P.O. Box 801, Nashville, TN 37202-0801 or e-mailed to [email protected]. Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyrighted © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America, and are used by permission. -

Black and Blue 33.092 1974 Grande Parade Du Jazz Black and Blue 950.504

Jazz Interpret Titel Album/Single Label / Nummer Jahr «Nice All Stars» black and blue 33.092 1974 Grande Parade du Jazz black and blue 950.504 Abdul-Malik Ahmed The Music of New Jazz NJ 8266 1961, 2002 Adams Pepper 10 TO 4 AT THE 5 SPOT Riverside 12-265 1958, 1976 Adderley Julian "Cannonball" in the land of EmArcy MG 36 077 1956 Adderley Cannonball sophisticated swing EmArcy MG 36110 Adderley Cannonball Jump for Joy Mercury MG 36146 1958 Adderley Cannonball TAKES CHARGE LANDMARKLLP-1306 1959, 1987 Adderley Cannonball African Waltz Riverside OJC-258 (RLP-9377) 1961 Adderley Cannonball Quintet Plus Riverside OJC-306 (RLP-9388) 1961 Adderley Cannonbal Sextet In New York Riverside OJC-142 (RLP-9404) 1962 Adderley Cannonball Cannonball in Japan Capitol ECJ-50082 1966 Adderley Cannonball Masters of jazz EMI Electrola C 054-81 997 1967 Adderley Cannonball Soul of the Bible SABB-11120 1972 Adderley Cannonball Nippon Soul Riverside OJC-435 (RLP-9477) 1990 Adderley Cannonball The quintet in San Francisco feat. Nat Adderley Riverside OJC-035 (RLP-1157) Adderley Cannonball Know what I mean ? with Bill Evans Riverside RLP 9433, alto AA 021 Adderley Julian Portrait of Cannonball Riverside OJC-361 (RLP-269) 1958 Adderley Nat We remember Cannon In + Out Records 7588 1991 Adderley with Milt Jackson Things are getting better Riverside OJC-032 (RLP-1128) 1958 Adderly Julian "Cannonball" & strings 1955 Trip Jazz TLP-5508 Albam Manny Jazz lab vol.1 MCA Coral PCO 7177 1957, 1974 Alexander Monty Monty strikes again MPS 68.044 1974, 1976 Alexander Monty Overseas -

When I Don't Desire

I Don'tDesireGod.46522.i04.qxd 8/13/04 3:02 PM Page 3 When I Don’t Desire GOD How to Fight for Joy John Piper CROSSWAY BOOKS A DIVISION OF GOOD NEWS PUBLISHERS WHEATON, ILLINOIS I Don'tDesireGod.46522.i04.qxd 8/13/04 3:02 PM Page 4 When I Don’t Desire God Copyright © 2004 by Desiring God Foundation Published by Crossway Books A division of Good News Publishers 1300 Crescent Street Wheaton, Illinois 60187 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided by USA copyright law. Italics in biblical quotes indicate emphasis added. Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations are taken from: The Holy Bible: English Standard Version, copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a division of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture references marked NASB are from the New American Standard Bible®, copyright © by The Lockman Foundation 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995. Used by permission. Scripture references marked KJV are taken from the King James Version. Scripture references marked RSV are taken from the Revised Standard Version, copyright © 1946, 1971 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. Cover design: Josh Dennis First printing, 2004 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Piper, John, 1946- When I don’t desire God : how to fight for joy / John Piper. -

SWR2 Musikstunde

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT ESSAYS FEATURES KOMMENTARE VORTRÄGE SWR2 Musikstunde Pray(ing) & Play(ing) Glaubensfragen in der Jazzgeschichte (2) Von Julia Neupert Sendung: Mittwoch, 27. Mai 2015 9.05 – 10.00 Uhr Redaktion: Ulla Zierau Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Mitschnitte auf CD von allen Sendungen der Redaktion SWR2 Musik sind beim SWR Mitschnittdienst in Baden-Baden für € 12,50 erhältlich. Bestellungen über Telefon: 07221/929-26030 Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2-Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de 2 Signet SWR2 Musikstunde {00:10} AT Glaubensfragen in der Jazzgeschichte: Zu Teil II von „Pray(ing) and Play(ing) begrüßt Sie Julia Neupert! Musikbett Musikstunde {00:16} AT Aufgewachsen in einem oft tief-gläubigen Umfeld, haben viele Jazzmusikerinnen und Musiker Religion als ganz selbstverständlichen Teil ihres Lebens verstanden – und keinen Widerspruch gesehen zu dem eher lasterhaften Image, das ihrer Kunstform lange Zeit nachhing: Der Jazz von der Straße, aus den Bordellen, Nachtclubs und Drogenhöllen als Ausdruck von Gotteslob? Das stieß bei einigen Kirchenkonservativen auch auf Ablehnung. “Ist Jazz Sünde mit Synkopen?“ So war 1921 ein Artikel im „Women’s Home Journal“ überschrieben: Darin ist dann unter anderem von Jazz als ursprünglichem Voodoo-Phänomen die Rede: barbarische Musik, vor deren demoralisierender Wirkung man sich hüten müsse. -

![Morgenstern, Dan. [Record Review: Freddie Hubbard: Sky Dive] 40:10 (May 24, 1973)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6115/morgenstern-dan-record-review-freddie-hubbard-sky-dive-40-10-may-24-1973-7896115.webp)

Morgenstern, Dan. [Record Review: Freddie Hubbard: Sky Dive] 40:10 (May 24, 1973)

II · ·d .. · · ·. · ··..·d., b Mi-·ke·_BourneBill Cole Gary Giddins. Wayne Jones. Larry Kart. Peter Recor sarerev1ewe . Y . · : . · · M. D · r ,. Ke · · · · J . H. Kle·e Michael Levin. John Lttwe1ler. Terry Martin. John c onough. Dan . epnews, oe . , . · . R . · . L R'dl R Morgenstern. Bobby Nelsen. Don Nelsen. Bob Porter Doug amsey .. arry • I ey: og_er Riggins: ·Robert Rusch, James p; Schaffer. Joe Shulman. Harvey Siders. Will Smith. Jim Szantor. EricVogel. andPeteWeld1ng. Rating~are:*****exceltent, ****verygood,***good. ** fair, *poor . ..Most recordings-re'iiewed area 11~ilable for purchase through.the ~o~n b1.tat/R~CORD CLUB. · . (For membership information s!:ledetails elsewher!:l in, this issue. or.write to REVIEWS · downbeat!RE:CORDCLUB. ~2W.Adams,_Ch1cago, IL 60606) hear the sounds of this great musical organ Art, Francisco Centenno. are on the record SPOTLIGHTREVIEW ism, and of the individual voices, the _very ing. Perhaps it could be called nepotism. but DUKE ELLINGTON special voices, of which it is made ~P- L1st~n maybe it's just a natural desire for an Adder to some really contemporary music - music ley dynasty. -klee LATINAMERICAN SUITE-Fantasy 8419-Ocl by which our children's children will judge upaca;'Chico Cuadradino; Eque; Tina; The Sleep FREDDIEHUBBARD ing Lady and the Giant Who Watches Over Her; our age and perhaps not find it entirely ~ant Latin American Sunshine; Brasilliance. ing in the creation of lasting beauty. Listen SKY DIVE-CTI 6018: Povo; In A Mist; The Personnel: Willie Cook. Cat Anderson. Cootie and learn to love. -morgenstern Godfather; Sky Dive. Williams. Mercer Ellington. trump!='ts; Chuck Personnel: Hubbard. -

Boyhood and Other Days in Georgia

Boyhood and Other Days in Georgia BY George W Yarbrough, D.D. Superannuate Member or the North Georgia Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South Edited by H. M. DU BOSE, D.D. BOOK EDITOR METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH, SOUTH NASHVILLE, TENN. DALLAS, TEX.J RICHMOND, VA. PUBLISHING HOUSE OF THE M. E. CHURCH, SOUTH SMITH & LAMAR, AGENTS 1917 EDITOR'S NOTE Biography is the soul of history; without it the annals of no nation would possess relevancy or carry a teaching force. The present volume belongs to the class of biography, but it is biography of a unique character; it is doubtful if it has a parallel in our literature. During the latter years of a min- isterial career of more than half a century, Dr. George W Yarbrough, one of the veteran itinerants of the North Georgia Annual Conference, has been associating his maturest thoughts on all great subjects and the results of his happiest medita- tions with a record of the passing incidents and reminiscences of his life. These records have taken shape in a series of newspaper articles which, from the printing of the first, many years ago, attracted general attention in the Church and have been repeatedly called for in the permanent form of a book. To these reminiscential writings have been added several dis- courses and addresses which, for the most part, are carried along with the same historical and reminiscential current. Also there have been added some personal sketches and stories which give to the volume a delightful flavor of quaintness and indigenous humor. -

CANNONBALL ADDERLEY: the Black Messiah (2-CD Set)

SELLING POINTS: CANNONBALL ADDERLEY: • Cannonball Adderley Was a Mainstay The Black Messiah (2-CD Set) of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue Band and Was a Charting Solo Artist During the In 1970, Cannonball Adderley recorded a series of concerts that resulted in three cult ‘60s (“Mercy, Mercy, Mercy”) classic live albums, of which this double-album—produced, like other landmark double albums of the time like Soul Zodiac and Soul of the Bible, by David Axelrod—is the • The Black Messiah Was One of a hardest to find. It captures Cannonball and the Quintet (brother Nat Adderley on Celebrated Series of Collaborations cornet, Roy McCurdy on drums, Walter Booker on bass and George Duke—fresh with Producer David Axelrod from replacing Joe Zawinul, who had left to form Weather Report—on keyboards) at • Featured Quintet of Nat Adderley, the forefront of the burgeoning electronic jazz-rock fusion movement, sounding at Roy McCurdy, Walter Booker and times every bit like the early ‘70s band of Cannonball’s former bandleader Miles George Duke Davis, except maybe even funkier and more out there. But Cannonball always had a populist streak to him—after all, the man had a Top 20 hit with “Mercy, Mercy, • Guests Included Airto Moreira, Mercy”—and so The Black Messiah also features flat-out rock and roll (guest Alvin Battiste, Ernie Watts, Buck Clark guitarist Mike Deasy’s “Liittle Benny Hen”) as well as dips into the soul-jazz style and Mike Deasy that had landed him on the charts several years earlier, all punctuated by his always • Recorded Live at the Troubadour in entertaining between-song raps.