An Assessment of Local Perceptions Towards Natural Resource Management Practices in the Tuvalu Islands, South Pacific

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Action Plan for Implementing the Convention on Biological Diversity's Programme of Work on Protected Areas

Action Plan for Implementing the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Programme of Work on Protected Areas (INSERT PHOTO OF COUNTRY) (TUVALU) Submitted to the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity October 6, 2011 Protected area information: PoWPA Focal Point: Mrs. Tilia Asau Assistant Environment officer-Biodiversity Department of Environment Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Trade, Tourism, Environment & Labour. Government of Tuvalu. Email:[email protected] Lead implementing agency: Department of Environment. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Trade, Tourism, Environment & Labour. Multi-stakeholder committee: Advisory Committee for Tuvalu NBSAP project Description of protected area system National Targets and Vision for Protected Areas Vission: “Keeping in line with the Aichi targets - By the year 2020, Tuvalu would have a clean and healthy environment, full of biological resources where the present and future generations of Tuvalu will continue to enjoy the equitable sharing benefits of Tuvalu’s abundant biological diversity” Mission: “We shall apply our traditional knowledge, together with innovations and best practices to protect our environment, conserve and sustainably use our biological resources for the sustainable benefit of present and future Tuvaluans” Targets: Below are the broad targets for Tuvalu as complemented in the Tuvalu National Biodiversity Action Plan and NSSD. To prevent air, land , and marine pollution To control and minimise invasive species To rehabilitate and restore degraded ecosystems To promote and strengthen the conservation and sustainable use of Tuvalu’s biological diversity To recognize, protect and apply traditional knowledge innovations and best practices in relation to the management, protection and utilization of biological resources To protect wildlife To protect seabed and control overharvesting in high seas and territorial waters Coverage According to World data base on Protected Areas, as on 2010, 0.4% of Tuvalu’s terrestrial surface and 0.2% territorial Waters are protected. -

South Pacific

South Pacific Governance in the Pacific: the dismissal of Tuvalu's Governor-General Tauaasa Taafaki BK 338.9 GRACE FILE BARCOOE ECO Research School of Pacific and Asian \\\\~ l\1\1 \ \Ul\\ \ \\IM\\\ \\ CBR000029409 9 Enquiries The Editor, Working Papers Economics Division Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University Canberra 0200 Australia Tel (61-6) 249 4700 Fax (61-6) 257 2886 ' . ' The Economics Division encompasses the Department of Economics, the National Centre for Development Studies and the Au.§.tralia-J.apan Research Centre from the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, the Australian National University. Its Working Paper series is intended for prompt distribution of research results. This distribution is preliminary work; work is later published in refereed professional journals or books. The Working Papers include V'{Ork produced by economists outside the Economics Division but completed in cooperation with researchers from the Division or using the facilities of the Division. Papers are subject to an anonymous review process. All papers are the responsibility of the authors, not the Economics Division. conomics Division Working Papers " South Pacific Governance in the Pacific: the dismissal of Tuvalu's Governor-General Tauaasa Taafaki / o:,;7 CJ<,~ \}f ftl1 L\S\\ltlR~ Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies C;j~••• © Economics Division, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, 1996. This work is copyright. Apart from those uses which may be permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 as amended, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. -

Basic Design Study Report on the Project for Construction of the Inter-Island Vessel for Outer Island Fisheries Development

BASIC DESIGN STUDY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR CONSTRUCTION OF THE INTER-ISLAND VESSEL FOR OUTER ISLAND FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT IN TUVALU January, 2001 Japan International Cooperation Agency Fisheries Engineering Co., Ltd. PREFACE In response to a request from the Government of Tuvalu, the Government of Japan decided to conduct a basic design study on the Project for Construction of the Inter-Island Vessel for Outer Island Fisheries Development in Tuvalu and entrusted the study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA sent to Tuvalu a study team from August 1 to August 28, 2000. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of Tuvalu, and conducted a field study at the study area. After the team returned to Japan, further studies were made. Then, a mission was sent to Tuvalu in order to discuss a draft basic design, and as this result, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of Tuvalu for their close cooperation extended to the teams. January, 2001 Kunihiko Saito President Japan International Cooperation Agency List of Tables and Figures Table 1 Nivaga II Domestic Cargo and Passengers in 1999 ....................................................8 Table 2 Average Passenger Demand by Island Based on Population Ratios .............................9 Table 3 Crew Composition on the Plan Vessel as Compared with the Nivaga II .................... 14 Table 4 Number of Containers Unloaded at Funafuti Port ................................................... -

![Sector Assessment (Summary): Transport (Water Transport [Nonurban])](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5336/sector-assessment-summary-transport-water-transport-nonurban-205336.webp)

Sector Assessment (Summary): Transport (Water Transport [Nonurban])

Outer Island Maritime Infrastructure Project (RRP TUV 48484) SECTOR ASSESSMENT (SUMMARY): TRANSPORT (WATER TRANSPORT [NONURBAN]) Sector Road Map 1. Sector Performance, Problems, and Opportunities 1. Tuvalu is an independent constitutional monarchy in the southwest Pacific Ocean. Formerly known as the Ellice Islands, they separated from the Gilbert Islands after a referendum in 1975, and achieved independence from the United Kingdom on 1 October 1978. The population of 10,100 live on Tuvalu’s nine atolls, which have a total land area of 27 square kilometers. 1 The nine islands, from north to south, are Nanumea, Niutao, Nanumaga, Nui, Vaitupu, Nukufetau, Funafuti, Nukulaelae, and Niulakita. 2. About 43% of the population lives on the outer islands. The small land mass, combined with infertile soil, create a heavy reliance on the sea. The primary economic activities are fishing and subsistence farming, with copra being the main export. 3. The effectiveness and efficiency of maritime transport is highly correlated and integral to the economic development of Tuvalu. Government-owned ships are the only means of transport among the islands. The government fleet includes three passenger and cargo ships operated by the Ministry of Communication and Transport (MCT), a research boat under the Fishery Department, and a patrol boat. 2 The passenger and cargo ships travel from Funafuti to the outer islands and Fiji, so each island only has access to these ships once every 2–3 weeks. Table 1 shows the passengers and cargo carried by the ships in recent years. In addition to the regular services, these ships are used for medical evacuations. -

Questionnaire: Tuvalu 1. Description 1.1 Name(S) of Society, Language, and Language Family: Tuvalu, Tuvaluan, Tuvalu Is in the Austronesian Language Family (1)

Questionnaire: Tuvalu 1. Description 1.1 Name(s) of society, language, and language family: Tuvalu, Tuvaluan, Tuvalu is in the Austronesian language family (1) 1.2 ISO code (3 letter code from ethnologue.com): TVL (1) 1.3 Location (latitude/longitude): The latitude and longitude for Tuvalu are 8 00’S 178 00’E (2) 1.4 Brief history: “The first settlers were from Samoa and probably arrived in the 14th century ad. Niulakita, the smallest and southernmost island, was uninhabited before European contact; the other islands were settled by the 18th century, giving rise to the name Tuvalu, or “Cluster of Eight.” Europeans first discovered the islands in the 16th century through the voyages of Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira, but it was only from the 1820s, with visits by whalers and traders, that they were reliably placed on European charts. In 1863 labor recruiters from Peru kidnapped some 400 people, mostly from Nukulaelae and Funafuti, reducing the population of the group to less than 2,500. Concern over labor recruiting and a desire for protection helps to explain the enthusiastic response to Samoan pastors of the London Missionary Society who arrived in the 1860s. By 1900, Protestant Christianity was firmly established. With imperial expansion the group, then known as the Ellice Islands, became British protectorate in 1892 and part of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony in 1916. There was a gradual expansion of government services, but most administration was through island governments supervised by a single district officer based in Funafuti. Ellice Islanders sought education and employment at the colonial capital in the Gilbert group or in the phosphate industry at Banaba or Nauru. -

Les Îles Tuvalu : Du Risque De La Montée De L'océan Pacifique À La

Les îles Tuvalu : du risque de la montée de l’Océan Pacifique à la problématique des réfugiées climatiques Les îles Tuvalu : du risque de la montée de l’Océan Pacifique à la problématique des réfugiés climatiques Mémoire de Licence 3 Les Grands Défis Mondiaux LEJEUNE Olivier LOZACHMEUR Martin MENNESSON Joy PLANTIER Julien SCHMIDT Agathe Année universitaire 2008/2009 WEINBRENNER Daniel Mémoire de Licence 3 Page 1 sur 56 2008/2009 Les îles Tuvalu : du risque de la montée de l’Océan Pacifique à la problématique des réfugiées climatiques « L’humanité ne se définit pas par ce qu’elle crée, mais par ce qu’elle choisit de ne pas détruire. » Edward Osborne Wilson (Entomologiste et biologiste américain) Mémoire de Licence 3 Page 2 sur 56 2008/2009 Les îles Tuvalu : du risque de la montée de l’Océan Pacifique à la problématique des réfugiées climatiques Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 Localisation multiscalaire de l’archipel de Tuvalu .................................................................... 6 Carte de la morphologie des différents atolls de l’archipel de Tuvalu................................... 7 1. Les dérèglements climatiques : des enjeux majeurs ......................................................... 8 1.1. Les variations du niveau de l’Océan Pacifique ............................................................... 8 1.1.1. La montée du niveau des océans : définition et caractéristiques.............................. 8 -

Metronome Trip 1 to Nanumea, Nanumaga and Niutao, 18 June - 4 July 2016

Tuvalu Fisheries Department: Coastal Section: Trip Report Metronome Trip 1 to Nanumea, Nanumaga and Niutao, 18 June - 4 July 2016 Lale Petaia, Semese Alefaio, Tupulaga Poulasi, Viliamu Petaia, Filipo Makolo, Paeniu Lopati, Manuao Taufilo, Maani Petaia, Simeona Italeli, Leopold Paeniu, Tetiana Panapa, Aso Veu 9th August 2016 The mission After nearly a month of preparation, the mission to fulfil the first metronome trip under the NAPA II project was made to the three northern islands (Niutao, Nanumea & Nanumaga). The team mission includes several fisheries officers from both the coastal and the Operational and Development division, two NAPA II officers and three other staffs from other government departments. The full list of the team is provided on the appendix. Although, there were many target activities conducted during this mission, however, the focus of this report is to highlight specific activities that were undertaken specifically by the coastal division staffs during this trip. The overall objective of the mission is to implement fisheries related activities under component 1 of the NAPA II project. These are; I. House hold surveys on socio-economic data II. Collection of Ciguatera data III. Run creel survey trials IV. Canoe and boat survey V. LMMA work VI. Collection of fishery information and data The mission departed Funafuti on 18th June, and return on 4th July. The first island to visit was Niutao, where we stayed for 9 days. The visit to Niutao was the longest out of the three islands due to the unexpected problem we encounter during our stay on the island which will be mention later on this report. -

Tuvalu: Global Economic Crisis

Global Economic Crisis Sentinel Site Monitoring Final Outcome Document (TUVALU) UNDP & UNICEF PROJECT Millennium Development Goals Project in Economic Planning and Budgeting Department Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning Government of Tuvalu 23rd November – 18th December, 2009 Author: Ms. Grace Alapati Statistics Officer for Tuvalu & GEC National Consultant EXECUTIVE SUMMERY Contextual study identifying the impacts of the global economic crisis across the Pacific is a work in progress. The UNICEF organization has recently proposed and implemented programs throughout the Pacific that study the current and likely potential social impact of the crisis. The emerging challenges towards the poor arises from the crisis should be now fundamentally considered, thus addressed with strategic key solutions. The poor population are the most vulnerable beings in related to the crisis. Households with many children, inactive youths to earn income and related means to sustain living standards, more women and those with large households sizes have obviously unhappy in obtaining households compulsories. The cost of essential consumer goods and services is noticeably increasing over the pass years. Households with inactive seafarers are desperate for paid employment. This version reports important crisis matters focusing on the impacts at national and community levels. The impacts of the crisis were investigated and categorized into certain identified modules. They are the Health, Nutrition, Education and finally the Economy module. A country real‐time vulnerability data is targeted to produce within a period of 2years to inform and guide assessment of policy decisions that may be established. The document however may assist planners to better understand the situations of the poor particularly how they cope with the crisis. -

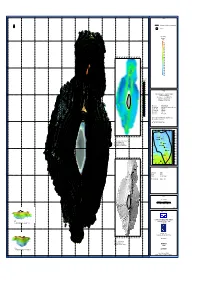

Nanumanga Tuvalu Bathymetry

414000 E 416000 E 418000 E 420000 E 422000 E 424000 E 426000 E 428000 E 430000 E 432000 E 434000 E LEGEND 150 Bathymetric contours shown at 20 metre intervals Land area Colour Banding Bathymetry Metres 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 420000 421000 422000 423000 424000 425000 426000 427000 428000 429000 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 2100 Slope angle (degrees) 80 75 70 65 60 NOTES 55 Observed soundings have been reduced to Chart Datum 50 defined as 0.7859 m below LAT, 45 1.985 m below mean sea level (MSL 1993-1994), 40 and 4.0123 m below the fixed height of Benchmark 22 on Funafuti, Tuvalu 35 30 25 Date of Survey 08/09 to 24/10/2004 20 Acquisition system Reson SeaBat 8160 multibeam echosounder Collection software Hypack 4.3 15 Processing software Hypack 4.3A 10 Data presentation Surfer 8.03 5 Survey vessel M.V. Turagalevu 0 Backdrop image is a 2003 IKONOS satellite image rectified using differential GPS ground control points. NOT TO BE USED FOR NAVIGATION LOCATION 0 m 4° S 500 m 1000 m 9298000 9299000 9300000 9301000 9302000 9303000 9304000 9305000 9306000 9307000 9308000420000 9309000 9310000 9311000 9312000 9313000 421000 422000 423000 424000 425000 426000 427000 428000 429000 9298000 9299000 9300000 9301000 9302000 9303000 9304000 9305000 9306000 9307000 9308000 9309000 9310000 9311000 9312000 9313000 Nanumea 6° S 1500 m INSET Nanumanga Niutao Gradient slope angle map generated from 20 m 2000 m gridded multibeam bathymetry. Nui Red indicates higher slope angles. -

Tuvalu National Environment Management Strategy 2015-2020

Pacific Environment Forum 18th September 2017 Tanoa Tusitala, Apia, samoa. TUVALU NATIONAL ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT STRATEGY 2015-2020 Connecting the Dots: Environment, Knowledge and Governance TUVALU OVERVIEW Tuvalu formally known as the Ellice islands, located in the Southwest of the Pacific Ocean between latitudes 5 degrees and 11 degrees south and longitudes 176 degrees and 180 degrees east. The islands include Niulakita, Nukulaelae, Funafuti, Nukufetau, Vaitupu, Nui, Niutao, Nanumaga and Nanumea. Tuvalu’s total land area is no more than 27 square kilometers. All of the islands are less than 5 meters above sea level (Tuvalu NBSAP 2009) 2012 Population census indicated a 10,782 total population with a 13.7% increase since the 2002 census. Census also indicated a large inter island movement from outer islands to Funafuti (Capital island) (urban pull) Environment Challenges in Tuvalu 1. Growing urbanisation on Funafuti 2. Limited land resources faces increased pressure from population growth 3. Reduction of trees due to excessive infrastructure development. 4. Waste management and direct implications for human and ecosystem health especially in Funafuti 5. Climate change and sea level rise, specifically salt-water inundation of roots crops (pulaka pits) coastal erosion and flooding 6. Oil Spill Government Commitment Under the National Strategy for Sustainable Development (NSSD) the priorities and strategies for environment management are to; 1. Develop and implement an urban and waste management plan for Funafuti 2. Establish national climate change adaptation and mitigation policies 3. Encourage international adoption of MEAs including the Kyoto Protocol 4. Increase the number of conservation areas and ensure regulatory compliance Rationale for the Tuvalu National Environment Management Strategy; • Assist the Government in its directions to restore and rehabilitate the deteriorating environment. -

Tuvalu Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report No. 3.Pdf

Tuvalu: Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report No. 3 (as of 9 April 2015) This report is produced by the OCHA Regional Office for the Pacific (ROP) in collaboration with the Government of Tuvalu and the Pacific Humanitarian Team. It covers the period from 27 to 31 March 2015. Highlights The highlights below are based on the information from the central, northern and southern islands for the period 27-31 March 2015. The report includes new information from the agriculture and health teams that visited the northern and southern islands and public works team in Nui. • A total of 39 homes were totally destroyed (12 in Nui Island, 15 in Nanumea, and 12 in Nanumanga). • The Nanumanga clinic suffered severe infrastructure damage. • The clinic in Niutao Island was partially damaged. • Eleven graves in Nanumea Island were damaged, resulting in human remains being brought to the surface. • There are reports of increased mosquito and fly breeding and a strong stench from decaying organic matter in all six affected islands. • The Aedes Egypti mosquito, a known carrier of Dengue fever, was identified in the northern islands of Nanumea, Nanumanga and Niutao. • Communities are depending on canned food as home food production has been compromised by saltwater intrusion. • DFAT and MFAT have committed resources (funds) to support crop replanting and fisheries in the outer islands. • The state of emergency for TC Pam has been lifted. • A French military plane delivered emergency supplies including the school back packs from UNICEF that were awaiting delivery in Nadi, Fiji. • Teams of Red Cross Volunteers have been on the forefront of emergency response in the affected islands distributing emergency supplies and creating awareness on public health and hygiene as well as clean-up operations. -

Coastal Sedimentation, Erosion and Management of Southwest Nukufetau Atoll, Tuvalu

COASTAL SEDIMENTATION, EROSION AND MANAGEMENT OF SOUTHWEST NUKUFETAU ATOLL, TUVALU Chunting Xue SOPAC Secretariat September 1996 SOPAC Technical Report 238 This project was funded by the Government of the People's Republic of China [3] TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS............................................................................................................. 6 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 7 STUDY METHODS..................................................................................................................... 8 COASTAL GEOLOGY................................................................................................................ 9 SEDIMENT SUPPLY AND TRANSPORTATION ..................................................................... 17 COASTAL EROSION, ACCUMULATION AND CAUSES ........................................................ 22 CURRENT MEASUREMENTS IN THE CHANNEL .................................................................. 30 CONCLUSIONS ....................................................................................................................... 37 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR COASTAL MANAGEMENT........................................................ 38 REFERENCES........................................................................................................................