The Chinese Orchestra in Contemporary Singapore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Response Report

DSIAC TECHNICAL INQUIRY (TI) RESPONSE REPORT Top Global Researchers and Organizations in Low Observable Material Science Report Number: DSIAC -2019-1188 Completed October 2019 DSIAC is a Department of Defense Information Analysis Center MAIN OFFICE 4695 Millennium Drive Belcamp, MD 21017-1505 443-360-4600 REPORT PREPARED BY: Taylor Hegeman Office: DSIAC DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 24-10-2019 Technical Research Report 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER FA8075-14-D-0001 Top Global Researchers and Organizations in Low Observable 5b. GRANT NUMBER Material Science 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Taylor H. -

MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), Piano

MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano FRIDAY, JANUARY 18, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL FRIDAY, JANUARY 18, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano PROGRAM JOHN WILLIAMS For New York (b. 1932) (Trans. for band by Paul Lavender) FRANK TICHELI Acadiana (b. 1958) At the Dancehall Meditations on a Cajun Ballad To Lafayette IGOR ST R AVINSKY Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments (1882–1971) Lento; Allegro Largo Allegro Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano Intermission VITTORIO Symphony No. 3 for Band GIANNINI Allegro energico (1903–1966) Adagio Allegretto Allegro con brio CENTENNIAL NOTE Vittorio Giannini (1903–1966) was an Italian-American composer calls upon the band’s martial associations, with an who joined the Manhattan School of Music faculty in 1944, where he exuberant march somewhat reminiscent of similar taught theory and composition until 1965. Among his students were efforts by Sir William Walton. Along with the sunny John Corigliano, Nicolas Flagello, Ludmila Ulehla, Adolphus Hailstork, disposition and apparent straightforwardness of works Ursula Mamlok, Fredrick Kaufman, David Amram, and John Lewis. like the Second and Third Symphonies, the immediacy MSM founder Janet Daniels Schenck wrote in her memoir, Adventure and durability of their appeal is the result of considerable in Music (1960), that Giannini’s “great ability both as a composer and as subtlety in motivic and harmonic relationships and even a teacher cannot be overestimated. In addition to this, his remarkable in voice leading. personality has made him beloved by all.” In addition to his Symphony No. -

The Butterfly Lovers' Violin Concerto by Zhanhao He and Gang Chen By

The Butterfly Lovers’ Violin Concerto by Zhanhao He and Gang Chen By Copyright 2014 Shan-Ken Chien Submitted to the graduate degree program in School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson: Prof. Véronique Mathieu ________________________________ Dr. Bryan Kip Haaheim ________________________________ Prof. Peter Chun ________________________________ Prof. Edward Laut ________________________________ Prof. Jerel Hilding Date Defended: April 1, 2014 ii The Dissertation Committee for Shan-Ken Chien certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Butterfly Lovers’ Violin Concerto by Zhanhao He and Gang Chen ________________________________ Chairperson: Prof. Véronique Mathieu Date approved: April 17, 2014 iii Abstract The topic of this DMA document is the Butterfly Lovers’ Violin Concerto. This violin concerto was written by two Chinese composers, Gang Chen and Zhahao He in 1959. It is an orchestral adaptation of an ancient legend, the Butterfly Lovers. This concerto was written for the western style orchestra as well as for solo violin. The orchestra part of this concerto has a deep complexity of music dynamics, reflecting the multiple layers of the story and echoing the soloist’s interpretation of the main character. Musically the concerto is a synthesis of Eastern and Western traditions, although the melodies and overall style are adapted from the Yue Opera. The structure of the concerto is a one-movement programmatic work or a symphonic poem. The form of the concerto is a sonata form including three sections. The sonata form fits with the three phases of the story: Falling in Love, Refusing to Marry, and Metamorphosis. -

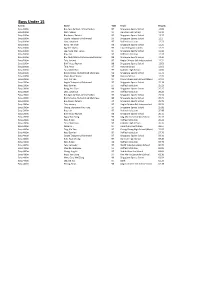

Boys Under 15

Boys Under 15 Events Name YOB Team Results Boys 100m Bin Agos Sahbali, Amirul Sofian 97 Singapore Sports School 12.09 Boys 100m Moh, Shaun 97 Dunman High School 12.11 Boys 100m Bin Anuar, Zuhairi 97 Singapore Sports School 12.17 Boys 100m Sugita Tadayoshi, Richmond 97 Singapore Sports School 12.2 Boys 100m Lew, Jonathon 97 Raffles Institution 12.23 Boys 100m Kang, Yee Cher 98 Singapore Sports School 12.25 Boys 100m Ng, Kee Hsien 97 Hwa Chong Institution 12.25 Boys 100m Lee, Song Wei, Lucas 97 Singapore Sports School 12.36 Boys 100m Poy, Ian 97 Raffles Institution 12.37 Boys 100m Bin Abdul Wahid, Muhammad Syazani 98 Singapore Sports School 12.44 Boys 100m Toh, Jeremy 97 Anglo Chinese Sch Independant 12.51 Boys 100m Bin Fairuz, Rayhan 98 Singapore Sports School 12.63 Boys 100m Thia, Aven 97 Victoria School 12.63 Boys 100m Tan, Chin Kean 97 Catholic High School 12.66 Boys 100m Bin Norzaha, Muhammad Shahrieza 98 Singapore Sports School 12.72 Boys 100m Chen, Ryan Shane 98 Victoria School 12.73 Boys 200m Ong, Xin Yao 97 Chung Cheng High School (Main) 24.91 Boys 200m Sugita Tadayoshi, Richmond 97 Singapore Sports School 25.18 Boys 200m Kee, Damien 97 Raffles Institution 25.23 Boys 200m Kang, Yee Cher 98 Singapore Sports School 25.25 Boys 200m Lew, Jonathon 97 Raffles Institution 25.26 Boys 200m Bin Agos Sahbali, Amirul Sofian 97 Singapore Sports School 25.50 Boys 200m Bin Norzaha, Muhammad Shahrieza 98 Singapore Sports School 25.71 Boys 200m Bin Anuar, Zuhairi 97 Singapore Sports School 25.72 Boys 200m Toh, Jeremy 97 Anglo Chinese Sch Independant -

The Chinese Phonetic Transcriptions of Old Turkish Words in the Chinese Sources from 6Th -9Th Century Focused on the Original Word Transcribed As Tujue 突厥*

The Chinese Phonetic Transcriptions of Old Title Turkish Words in the Chinese Sources from 6th - 9th Century : Focused on the Original Word Transcribed as Tujue 突厥 Author(s) Kasai, Yukiyo Citation 内陸アジア言語の研究. 29 P.57-P.135 Issue Date 2014-08-17 Text Version publisher URL http://hdl.handle.net/11094/69762 DOI rights Note Osaka University Knowledge Archive : OUKA https://ir.library.osaka-u.ac.jp/ Osaka University 57 The Chinese Phonetic Transcriptions of Old Turkish Words in the Chinese Sources from 6th -9th Century Focused on the Original Word Transcribed as Tujue 突厥* Yukiyo KASAI 0. Introduction The Turkish tribes which originated from Mongolia contacted since time immemorial with their various neighbours. Amongst those neighbours China, one of the most influential countries in East Asia, took note of their activities for reasons of its national security on the border areas to the North of its territory. Especially after an political unit of Turkish tribes called Tujue 突厥 had emerged in the middle of the 6th c. as the first Turkish Kaganate in Mongolia and become threateningly powerful, the Chinese dynasties at that time followed the Turks’ every move with great interest. The first Turkish Kaganate broke down in the first half of the 7th c. and came under the rule of the Chinese Tang 唐–dynasty, but * I would like first to express my sincere thanks to Prof. Dr. DESMOND DURKIN-MEISTERERNST who gave me useful advice about the contents of this article and corrected my English, too. My gratitude also goes to Prof. TAKAO MORIYASU and Prof. -

A Review of the Origin and Evolution of Uygur Musical Instruments

2019 International Conference on Humanities, Cultures, Arts and Design (ICHCAD 2019) A Review of the Origin and Evolution of Uygur Musical Instruments Xiaoling Wang, Xiaoling Wu Changji University Changji, Xinjiang, China Keywords: Uygur Musical Instruments, Origin, Evolution, Research Status Abstract: There Are Three Opinions about the Origin of Uygur Musical Instruments, and Four Opinions Should Be Exact. Due to Transliteration, the Same Musical Instrument Has Multiple Names, Which Makes It More Difficult to Study. So Far, the Origin of Some Musical Instruments is Difficult to Form a Conclusion, Which Needs to Be Further Explored by People with Lofty Ideals. 1. Introduction Uyghur Musical Instruments Have Various Origins and Clear Evolution Stages, But the Process is More Complex. I Think There Are Four Sources of Uygur Musical Instruments. One is the National Instrument, Two Are the Central Plains Instruments, Three Are Western Instruments, Four Are Indigenous Instruments. There Are Three Changes in the Development of Uygur Musical Instruments. Before the 10th Century, the Main Musical Instruments Were Reed Flute, Flute, Flute, Suona, Bronze Horn, Shell, Pottery Flute, Harp, Phoenix Head Harp, Kojixiang Pipa, Wuxian, Ruan Xian, Ruan Pipa, Cymbals, Bangling Bells, Pan, Hand Drum, Iron Drum, Waist Drum, Jiegu, Jilou Drum. At the Beginning of the 10th Century, on the Basis of the Original Instruments, Sattar, Tanbu, Rehwap, Aisi, Etc New Instruments Such as Thar, Zheng and Kalong. after the Middle of the 20th Century, There Were More Than 20 Kinds of Commonly Used Musical Instruments, Including Sattar, Trable, Jewap, Asitar, Kalong, Czech Republic, Utar, Nyi, Sunai, Kanai, Sapai, Balaman, Dapu, Narre, Sabai and Kashtahi (Dui Shi, or Chahchak), Which Can Be Divided into Four Categories: Choral, Membranous, Qiming and Ti Ming. -

Springtime Is a Season of Senses Awakening

18 | Tuesday, March 9, 2021 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY LIFE Springtime is a season of senses awakening As a child growing up in a sub- urban town in the Northeast of the United States, the arrival of spring had little meaning for me. Sure, we had a weeklong spring vacation from school, but the operative word there was vacation, not spring. For the kids in my neighbor- hood, the arrival of spring was a non-event. There were two important seasons: winter, when we could go skating and sledding or build snow forts, and summer, when we could f-i-n-a-l-l-y make proper use of the beach about Left: Liu Jing, a promoter of traditional Chinese music and instruments, plays the pipa in the style of Tang Dynasty music. Middle and right: Liu in her work, Prelude to the 100 meters east of my family Konghou of Li Ping, a short video based on a namesake poem written by poet Li He from the Tang period. PHOTOS PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY home. Spring and autumn were just technical details, weeks and weeks of waiting for the good times’ return. And, even though the begin- The melody of our heritage John ning of autumn Lydon was a clearly Second demarcated event Instruments, once out of fashion, enjoy a surge of popularity as composer combines history Thoughts — summer vaca- tion abruptly fin- with music to provide the harmony of a bygone era, Wang Ru reports. ished, and it was back to school for an eternity of 10 months — t was a moment seared in her spring had little to distinguish memory. -

Historical and Contemporary Development of the Chinese Zheng

Historical and Contemporary Development of the Chinese Zheng by Han Mei MA, The Music Research Institute of Chinese Arts Academy Beijing, People's Republic of China, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (School of Music) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October, 2000 ©HanMei 2000 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT The zheng is a plucked, half-tube Chinese zither with a history of over two and a half millennia. During this time, the zheng, as one of the principal Chinese instruments, was used in both ensemble and solo performances, playing an important role in Chinese music history. Throughout its history, the zheng underwent several major changes in terms of construction, performance practice, and musical style. Social changes, political policies, and Western musical influences also significantly affected the development of the instrument in the twentieth century; thus the zheng and its music have been brought to a new stage through forces of modernization and standardization. -

HANDLING DESIGN SUPPORT PROGRAMMES COMPLEXITY an Interpretative Framework for Barriers and Drivers to Introducing Design Innovation Into Brazilian Msmes

HANDLING DESIGN SUPPORT PROGRAMMES COMPLEXITY An interpretative framework for barriers and drivers to introducing design innovation into Brazilian MSMEs Mariana Fonseca Braga HANDLING DESIGN SUPPORT PROGRAMMES COMPLEXITY An interpretative framework for barriers and drivers to introducing design innovation into Brazilian MSMEs Mariana Fonseca Braga, MSc Supervisor Francesco P. Zurlo, PhD Vice-Dean, School of Design, Politecnico di Milano Assistant supervisor Viviane dos Guimarães Alvim Nunes, PhD Dean, Faculdade de Arquitetura, Urbanismo e Design (FAUeD), Universidade Federal de Uberlândia (UFU) Controrelatore Gisele Raulik-Murphy, PhD Partner, DUCO - Driving Design Strategies Politecnico di Milano Department of Design PhD programme in Design 30th Cycle January 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research was supported by the Brazilian National Council for Scientifc and Technological De- velopment (CNPq), which made it possible. I am grateful to CNPq for this opportunity. I am indebted to the amazing people, who surrounded me in the Design Department at Politecnico di Milano, especially Prof. Francesco Zurlo, the best supervisor I might have, and the Creative Industries Lab (Cilab) staff, particularly Prof. Arianna Vignati. I also thank Prof. Marzia Mortati, from the Design Policy Lab, for the meaningful advice she has provided throughout this investigation. In addition, I had especial support from Prof. Viviane dos Guimarães Alvim Nunes, Prof. Gisele Rau- lik-Murphy, and from my friend, Prof. Silvia Xavier. I am really glad for your voluntary contributions to this research. I also thank all interviewees who told me their project’s stories, without them this research would lack meaningful insights, and the non-proft private entity, which provided information about two of its projects. -

Full Curriculum Vitae

Chenxiao.Atlas.Guo [email protected] Updated Aug 2021 atlasguo @cartoguophy atlasguo.github.io CURRICULUM VITAE EDUCATION University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison) (Madison, WI, USA; 2022 Expected) • Ph.D. in Geography (Cartography/GIS), Department of Geography - Core Courses: Graphic Designs in Cartography, Interactive Cartography & Geovisualization; Advanced Quantitative Analysis, Advanced Geocomputing and Big Data Analytics, Geospatial Database, GIS Applications; Seminars in GIScience (VGI; Deep Learning; Storytelling); Natural Hazards and Disasters (audit) • Doctoral Minor in Computer Science, Department of Computer Science - Core Courses: Data Structure, Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, Computer Graphics, Human-Computer Interaction, Machine Learning (audit) • Research Direction: Spatiotemporal Analytics, Cartographic Visualization, Social Media Data Mining, Natural Disaster Management (bridging geospatial data science, cartography, and social good) • Current GPA: 3.7/4.0 University of Georgia (UGA) (Athens, GA, USA; 2017) • M.S. in Geography (GIS), Department of Geography - Core Courses: Statistical Method in Geography, Geospatial Analysis, Community GIS, Programming for GIS, Seminars in GIScience, Geographic Research Method, Satellite Meteorology and Climatology, Seminar in Climatology, Urban Geography (audit), Psychology (audit) • Research Direction: Location-based Social Media, Sentiment Analysis, Urban Spatiality, Electoral Geography • GPA: 3.7/4.0 Sun Yat-Sen University (SYSU) (Guangzhou, China; 2015) • B.S. in Geographic -

Plucked Stringed Instruments

Plucked Stringed Instruments Fig. 2.1: The Pipa 18 Pipa 2 琵琶 Pipa HISTORY The grand dame of plucked stringed instruments, the pipa is one of the most expressive instruments in the Chinese orchestra (Fig. 2.1). Recent moves by some major Chinese orchestras include removing the instrument entirely from the orchestral formation due to its overpowering character and inability to blend. Its techniques, however, are applied to almost every plucked stringed instrument and its concepts have been borrowed for the reformations of various plucked stringed instruments. The term pipa used today refers to the lute-shaped instrument which comprises of four strings and a fretted soundboard of 20 to 25 frets. In the ancient Chinese dynasties of Sui and Han, the term pipa was generic for any instrument that was plucked or had a plucked string aspect to it. The word pipa is made up of two Chinese characters – 琵 pi and 琶 pa1. The words describe how the instrument is played and the sounds it produced. The forward plucking of the string using one’s right hand was termed pi, and the backward plucking of the string with the right hand was termed pa. The first recorded connotation to the word pipa was found in 刘熙 Liu Xi’s <<释名>> Shi Ming, where it was recorded as piba2. Although greatly associated with the Chinese, the pipa is not native to China; the instrument was introduced to China by Asia Minor over 2000 years ago. As the instrument is foreign, its counterparts in the forms of lutes and mandolins can still be found in Central and Western Asia. -

WUXI Wuxi: the “Little Shanghai”? Wuxi’S Rapid Industrial Development Has Earned a Spot on China’S Top 50 Cities, As Well As the Nickname – “Little Shanghai”

WUXI Wuxi: The “Little Shanghai”? Wuxi’s rapid industrial development has earned a spot on China’s top 50 cities, as well as the nickname – “Little Shanghai”. Yet amidst such impressive economic growth, the city has maintained its cultural and historical identity, and its charming natural beauty. What does the future hold? By AMANDA LI uxi’s unique- ness lies in its ability to offer culture, histo- ry and nature alongside with its developed urban centre, an element of individuality that has propelled the city into China’s top 10 tourist cities. Wuxi’s origins can be traced back to the end of the Shang Dynasty, with its name Wuxi (meaning “a place without tin”) emerging at the end of the Qin Dynasty, when its previously rich deposit of tin was depleted. Wuxi’s history spans a spectacular period of 3000 years, during which it claimed the title of “the Wuxi New District Pearl of Tai Lake” due to its role as the economic and political centre on the Wuxi’s origins can be traced back to the end of the south of the Yangtze River. Before the 19th century, for example, Wuxi served Shang Dynasty, with its name Wuxi (meaning “a place as an important city, boasting the busiest without tin”) emerging at the end of the Qin Dynasty, rice and cloth market in China at the time. Development in Wuxi continued when its previously rich deposit of tin was depleted. into the early 20th century as it became a hub for the textile (especially silk) indus- architecture, dialect, waterway transpor- More recently, Wuxi has fostered cul- try, and continued to grow as the People’s tation and in art.