Normal Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Experiences of Land Reform in the Northern Cape Province of South

PR cov no. 1 1/18/05 4:09 PM Page c POLICY & RESEARCH SERIES Key Experiences 1 of Land Reform in the Northern Cape Province of South Africa Alastair Bradstock January 2005 PR book no. 1 1/18/05 4:01 PM Page i POLICY & RESEARCH SERIES Key Experiences 1 of Land Reform in the Northern Cape Province of South Africa Alastair Bradstock January 2005 PR book no. 1 1/18/05 4:01 PM Page ii Editors: Jacqueline Saunders and Lynne Slowey Photographs: Pieter Roos Designer: Eileen Higgins E [email protected] Printers: Waterside Press T +44 (0) 1707 275555 Copies of this publication are available from: FARM-Africa, 9-10 Southampton Place London,WC1A 2EA, UK T + 44 (0) 20 7430 0440 F + 44 (0) 20 7430 0460 E [email protected] W www.farmafrica.org.uk FARM-Africa (South Africa), 4th Floor,Trust Bank Building, Jones Street PO Box 2410, Kimberley 8300, Northern Cape, South Africa T + 27 (0) 53 831 8330 F + 27 (0) 53 831 8333 E [email protected] ISBN: 1 904029 02 7 Registered Charity No. 326901 Copyright: FARM-Africa, 2005 Registered Company No. 1926828 PR book no. 1 1/18/05 4:01 PM Page iii FARM-Africa’s Policy and Research Series encapsulates project experiences and research findings from its grassroots programmes in Eastern and Southern Africa.Aimed at national and international policy makers, national government staff, research institutions, NGOs and the international donor community, the series makes specific policy recommendations to enhance the productivity of the smallholder agricultural sector in Africa. -

Rooibos Heritage Route Podcast Please Follow This Podcast As You Travel Along the Route

Rooibos Heritage Route Podcast Please follow this podcast as you travel along the route. We will install small plates with numbers to allow you to follow the points along the route easily. From Nieuwoudtville to Wupperthal From Wupperthal to Nieuwoudtville 1. Introduction 1. Introduction 2. Point 1: Nieuwoudtville 2. Point 28: Wupperthal 3. Point 2:Hantam National Botanical 3. Point 27: Heuningvlei Garden 4. Point 26: Sandwerf 4. Point 3:Dolerite Hills 5. Point 25: Citadel Kop 5. Point 4: Glacial Pavement 6. Point 24: Biedouw Valley 6. Point 5: Oorlogskloof 7. Point 23: Hoek se Berg 7. Point 6: Matjiesfontein Padstal 8. Point 22: Engelsman's Graf 8. Point 7: Moedverloor Pad 9. Rooibos 9. Point 8: Papkuilsfontein 10. Medicinal Plants 10. Point 9: Rietjieshuis 11. Point 21: Doringbos 11. Point 10: Fynbos 12. Point 20: Provincial Boundary 12. Point 11: View Point: Brandkop 13. Point 19: Welgemoed 13. Point 12: Heiveld Tea Court 14. Point 18: Moedverloor 14. Point 13: Blomfontein Farm 15. Point 17: School Cave 15. Point 14: Dammetjies Farm 16. Point 16: Kortkloof Viewpoint 17. Point 15: Sonderwaterkraal 16. Point 15: Sonderwaterkraal 18. Point 14: Dammetjies Farm 17. Point 16: Kortkloof Viewpoint 18. Point 17: School Cave 19. Point 13: Blomfontein Farm 19. Point 18: Moedverloor 20. Point 12: Heiveld Tea Court 20. Point 19: Welgemoed 21. Point 11: View Point: Brandkop 21. Point 20: Provincial Boundary 22. Point 10: Fynbos 22. Point 21: Doringbos 23. Point 9: Rietjieshuis 23. Rooibos 24. Point 8: Papkuilsfontein 24. Point 22: Engelsman's Graf 25. Point 7: Moedverloor Pad 25. -

6 the Environments Associated with the Proposed Alternative Sites

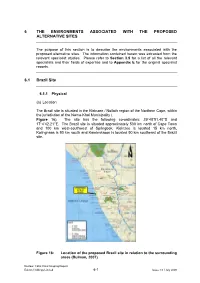

6 THE ENVIRONMENTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE PROPOSED ALTERNATIVE SITES The purpose of this section is to describe the environments associated with the proposed alternative sites. The information contained herein was extracted from the relevant specialist studies. Please refer to Section 3.5 for a list of all the relevant specialists and their fields of expertise and to Appendix E for the original specialist reports. 6.1 Brazil Site 6.1.1 Physical (a) Location The Brazil site is situated in the Kleinzee / Nolloth region of the Northern Cape, within the jurisdiction of the Nama-Khoi Municipality ( Figure 16). The site has the following co-ordinates: 29°48’51.40’’S and 17°4’42.21’’E. The Brazil site is situated approximately 500 km north of Cape Town and 100 km west-southwest of Springbok. Kleinzee is located 15 km north, Koiingnaas is 90 km south and Kamieskroon is located 90 km southeast of the Brazil site. Figure 16: Location of the proposed Brazil site in relation to the surrounding areas (Bulman, 2007) Nuclear 1 EIA: Final Scoping Report Eskom Holdings Limited 6-1 Issue 1.0 / July 2008 (b) Topography The topography in the Brazil region is largely flat, with only a gentle slope down to the coast. The coast is composed of both sandy and rocky shores. The topography is characterised by a small fore-dune complex immediately adjacent to the coast with the highest elevation of approximately nine mamsl. Further inland the general elevation depresses to about five mamsl in the middle of the study area and then gradually rises towards the east. -

A Case Study: Building Resilience in Rangelands Through a Natural Resource Management Model

A CASE STUDY: BUILDING RESILIENCE IN RANGELANDS THROUGH A NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT MODEL Ecosystem-based approaches to adaptation: strengthening the evidence and informing policy Halcyone Muller Heidi-Jayne Hawkins Sarshen Scorgie November 2019 Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 Materials and methods .................................................................................................... 6 Climate and biophysical characteristics of the study area ............................. 6 Socio-economic characteristics of the study area ............................................. 7 Socio-economic survey .............................................................................................. 7 Biophysical study design ........................................................................................... 7 Statistics .......................................................................................................................... 8 Results .................................................................................................................................. 10 Socio-economic survey ............................................................................................. 10 Biophysical study ......................................................................................................... 11 Discussion ......................................................................................................................... -

Explore the Northern Cape Province

Cultural Guiding - Explore The Northern Cape Province When Schalk van Niekerk traded all his possessions for an 83.5 carat stone owned by the Griqua Shepard, Zwartboy, Sir Richard Southey, Colonial Secretary of the Cape, declared with some justification: “This is the rock on which the future of South Africa will be built.” For us, The Star of South Africa, as the gem became known, shines not in the East, but in the Northern Cape. (Tourism Blueprint, 2006) 2 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module # 1 - Province Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Province Overview Module # 2 - Cultural Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Cultural Overview Module # 3 - Historical Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Historical Overview Module # 4 - Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Module # 5 - Namaqualand Component # 1 - Namaqualand Component # 2 - The Hantam Karoo Component # 3 - Towns along the N14 Component # 4 - Richtersveld Component # 5 - The West Coast Module # 5 - Karoo Region Component # 1 - Introduction to the Karoo and N12 towns Component # 2 - Towns along the N1, N9 and N10 Component # 3 - Other Karoo towns Module # 6 - Diamond Region Component # 1 - Kimberley Component # 2 - Battlefields and towns along the N12 Module # 7 - The Green Kalahari Component # 1 – The Green Kalahari Module # 8 - The Kalahari Component # 1 - Kuruman and towns along the N14 South and R31 Northern Cape Province Overview This course material is the copyrighted intellectual property of WildlifeCampus. It may not be copied, distributed or reproduced in any format whatsoever without the express written permission of WildlifeCampus. 3 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module 1 - Component 1 Northern Cape Province Overview Introduction Diamonds certainly put the Northern Cape on the map, but it has far more to offer than these shiny stones. -

National SEA for Aquaculture Development in South Africa Meeting Notes

National SEA for Aquaculture Development in South Africa Meeting Notes National Strategic Environmental Assessment for Aquaculture Development in South Africa Additional inputs to Focus Group Meetings #1 to #5 These additional inputs were made in writing by participants at the Focus Group meetings #1 to #5 held from 30 September to 07 October 2016, using the cards provided. List of acronyms AFASA Abalone Farmers Association of South Africa ARC Agricultural Research Council CPUT Cape Town University of Technology CSIR NRE Natural Resources and Environment CSIR Council for Scientific and Industrial Research DAFF Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries DEA Department of Environmental Affairs DRDLR Department of Rural Development and Land Reform DWS Department of Water and Sanitation DWS: IWU Department of Water and Sanitation: Integrated Water Use FS DARD Free State Department of Agriculture and Rural Development GDARD Gauteng Department of Agriculture and Rural Development LEDET Limpopo Department of Economic Development, Environment and Tourism MP DARDLEA Mpumalanga Department of Agriculture, Rural Development, Land and Environmental Affairs MTPA Mpumalanga Tourism and Parks Agency NC DENC Northern Cape Department of Environment and Nature Conservation NEPAD New Partnership for Africa’s Development NMBM Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality NW DREAD North West Department of Rural, Environment and Agricultural Development NWU North West University RU Rhodes University SAIAB South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity SANBI South African National Biodiversity Institute SEA Strategic Environmental Assessment SUN Stellenbosch University TSA Trout South Africa UFH University of Fort Hare UL University of Limpopo WWTW Wastewater Treatment Works 1 National SEA for Aquaculture Development in South Africa Meeting Notes Stellenbosch – Friday, 30 September 2016 Person Organisation Comments Sally Paulet AFASA & HIK Abalone Willing to help where possible regarding aquaculture Farm Pty Ltd facilities & their respective information. -

The Free State, South Africa

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development THE FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA The third largest of South Africa’s nine provinces, the Free State suffers from The Free State, unemployment, poverty and low skills. Only one-third of its working age adults are employed. 150 000 unemployed youth are outside of training and education. South Africa Centrally located and landlocked, the Free State lacks obvious regional assets and features a declining economy. Jaana Puukka, Patrick Dubarle, Holly McKiernan, How can the Free State develop a more inclusive labour market and education Jairam Reddy and Philip Wade. system? How can it address the long-term challenges of poverty, inequity and poor health? How can it turn the potential of its universities and FET-colleges into an active asset for regional development? This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system T impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other he Free State, South Africa higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. CONTENTS Chapter 1. The Free State in context Chapter 2. Human capital and skills development in the Free State Chapter 3. -

South Africa Yearbook 2012/13

SOUTH AFRICA YEARBOOK 2012/13 Land and its p Land and its people Situated at the southern tip of Africa, South Africa boasts an amazing variety of natural beauty and an abundance of wildlife, birds, Land and its p plant species and mineral wealth. In addi- tion, its population comprises a unique diversity of people and cultures. The southern tip of Africa is also where archaeologists discovered 2,5-million-year- old fossils of man’s earliest ancestors, as well as 100 000-year-old remains of modern man. The land Stretching latitudinally from 22°S to 35°S and longitudinally from 17°E to 33°E, South Africa’s surface area covers 1 219 602 km2. According to Census 2011, the shift of the national boundary over the Indian Ocean in the north-east corner of KwaZulu-Natal to cater for the Isimangaliso Wetland Park led to the increase in South Africa’s land area. Physical features range from bushveld, grasslands, forests, deserts and majestic mountain peaks, to wide unspoilt beaches and coastal wetlands. The country shares common bound- aries with Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Swaziland, while the Mountain Kingdom of Lesotho is landlocked by South African territory in the south-east. The 3 000-km shoreline stretching from the Mozambican border in the east to the Namibian border in the west is surrounded by the Atlantic and Indian oceans, which meet at Cape Point in the continent’s south- western corner. Prince Edward and Marion islands, annexed by South Africa in 1947, lie some 1 920 km south-east of Cape Town. -

Ncta Map 2017 V4 Print 11.49 MB

here. Encounter martial eagles puffed out against the morning excellent opportunities for river rafting and the best wilderness fly- Stargazers, history boffins and soul searchers will all feel welcome Experience the Northern Cape Northern Cape Routes chill, wildebeest snorting plumes of vapour into the freezing air fishing in South Africa, while the entire Richtersveld is a mountain here. Go succulent sleuthing with a botanical guide or hike the TOURISM INFORMATION We invite you to explore one of our spectacular route and the deep bass rumble of a black- maned lion proclaiming its biker’s dream. Soak up the culture and spend a day following Springbok Klipkoppie for a dose of Anglo-Boer War history, explore NORTHERN CAPE TOURISM AUTHORITY Discover the heart of the Northern Cape as you travel experiences or even enjoy a combination of two or more as territory from a high dune. the footsteps of a traditional goat herder and learn about life of the countless shipwrecks along the coast line or visit Namastat, 15 Villiers Street, Kimberley CBD, 8301 Tel: +27 (0) 53 833 1434 · Fax +27 (0) 53 831 2937 along its many routes and discover a myriad of uniquely di- you travel through our province. the nomads. In the villages, the locals will entertain guests with a traditional matjies-hut village. Just get out there and clear your Traveling in the Kalahari is perfect for the adventure-loving family Email: [email protected] verse experiences. Each of the five regions offers interest- storytelling and traditional Nama step dancing upon request. mind! and adrenaline seekers. -

A New Species of Rain Frog from Namaqualand, South Africa (Anura: Brevicipitidae: Breviceps)

Zootaxa 3381: 62–68 (2012) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2012 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new species of Rain Frog from Namaqualand, South Africa (Anura: Brevicipitidae: Breviceps) ALAN CHANNING Biodiversity and Conservation Biology Department, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville, 7525, South Africa. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Breviceps branchi sp. nov. is described from coastal Namaqualand, South Africa. It is most similar to Breviceps na- maquensis in colour pattern and overall form, from which it differs by hand and foot morphology and 16S rRNA sequence. Key words: Breviceps, new species, Namaqualand, 16S rRNA, South Africa Introduction The genus Breviceps is known from South Africa northwards to Kenya, and as far west as Angola, with the closely related Balebreviceps found in Ethiopia (IUCN 2011). There are presently 15 species recognised (Frost 2011). The early taxonomy of the genus Breviceps was reviewed by Power (1926), by which time seven species were already known, including the Namaqualand endemics, B. macrops and B. namaquensis. Power (1926) discussed a number of characters that might be useful in separating species of rain frogs. On the basis of differences in 16S rRNA and morphology, I describe a new species of Breviceps from Namaqualand. Material and methods Sampling. A single specimen was collected in Namaqualand, South Africa. A small tissue sample was removed from thigh muscle, and the specimen was fixed in formalin for 24 h, then transferred to 70% ethanol for deposition in the herpetological collection of the Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Research on Evolution and Biodiversity at the Humboldt University, Berlin (ZMB). -

Download This

TOWN PRODUCT CONTACT ATTRIBUTES ACCOMM CONTACT DETAILS DETAILS STEINKOPF Kookfontein Tel: 027-7218841 *Cultural Tours *Kookfontein 027-7218841 Rondawels Faks: 027-7218842 *Halfmens / Succulent Rondawels – Situated along the N7, E-mail: tours self catering / on about 60 km from [email protected] *Flower tours (during request Springbok on the way flower season) to Vioolsdrif, Cultural/field Calitz *Hiking / walking Steinkopf has a strong Guide 0736357021 tours Nama culture due to *Immanual Centre the strong Nama (Succulent Nursery) history inherited from *Kinderlê (sacred mass the past. grave of 32 Nama children) 24 hr Petrol Station; *Steinkopf High ATM / FNB; Surgery; School Choir (songs in Ambulance Service; Nama, Xhosa, German Shops/Take Aways; and Afrikaans Night Club; Pub; *Klipfontein (old Liquor Stores; Police watertower and Anglo Station. Boere War graves of British soldiers) PORT NOLLOTH Municipal Alta Kotze *Port Nolloth *Bedrock 027-851 8353 Offices 027-8511111 Museum *Guesthouse A small pioneering *Port Nolloth *Scotia Inn Hotel: 027-85 1 8865 harbour town on the Seafarms *Port Indigo Guest 027-851 8012 icy cold Atlantic *Harbour – experience house: Ocean, Port Nolloth is the rich history of the *Mcdougalls Bay 027-8511110 home to diamond coastal area Caravan Park & divers, miners and *Sizamile – a township Chalets fishers with with a rich culture and a *Muisvlak Motel: 027-85 1 8046 fascinatingly diverse long history of struggle *Country Club Flats: 0835555919 cultures. *Historical Roman Catholic Church – Self contained ATM/Banking (FNB) near the beach, one of holiday facilities and Service the oldest buildings accommodation: Station; Surgery; around *Daan deWaal 0825615256 Ambulance; Police *Willem *R. -

Flower Route Map 2014 LR

K o n k i e p en w R31 Lö Narubis Vredeshoop Gawachub R360 Grünau Karasburg Rosh Pinah R360 Ariamsvlei R32 e N14 ng Ora N10 Upington N10 IAi-IAis/Richtersveld Transfrontier Park Augrabies N14 e g Keimoes Kuboes n a Oranjemund r Flower Hotlines O H a ib R359 Holgat Kakamas Alexander Bay Nababeep N14 Nature Reserve R358 Groblershoop N8 N8 Or a For up-to-date information on where to see the Vioolsdrif nge H R27 VIEWING TIPS best owers, please call: Eksteenfontein a r t e b e e Namakwa +27 (0)79 294 7260 N7 i s Pella t Lekkersing t Brak u West Coast +27 (0)72 938 8186 o N10 Pofadder S R383 R383 Aggeneys Flower Hour i R382 Kenhardt To view the owers at their best, choose the hottest Steinkopf R363 Port Nolloth N14 Marydale time of the day, which is from 11h00 to 15h00. It’s the s in extended ower power hour. Respect the ower Tu McDougall’s Bay paradise: Walk with care and don’t trample plants R358 unnecessarily. Please don’t pick any buds, bulbs or N10 specimens, nor disturb any sensitive dune areas. Concordia R361 R355 Nababeep Okiep DISTANCE TABLE Prieska Goegap Nature Reserve Sun Run fels Molyneux Buf R355 Springbok R27 The owers always face the sun. Try and drive towards Nature Reserve Grootmis R355 the sun to enjoy nature’s dazzling display. When viewing Kleinzee Naries i R357 i owers on foot, stand with the sun behind your back. R361 Copperton Certain owers don’t open when it’s overcast.