Spatial and Temporal Patterns in the Diet of Barn Owl (Tyto Alba) in Cyprus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cheers Along! Wine Is Not a New Story for Cyprus

route2 Vouni Panagias - Ampelitis cheers along! Wine is not a new story for Cyprus. Recent archaeological excavations which have been undertaken on the island have confi rmed the thinking that this small tranche of earth has been producing wine for almost 5000 years. The discoveries testify that Cyprus may well be the cradle of wine development in the entire Mediterranean basin, from Greece, to Italy and France. This historic panorama of continuous wine history that the island possesses is just one Come -tour, taste of the reasons that make a trip to the wine villages such a fascinating prospect. A second and enjoy! important reason is the wines of today -fi nding and getting to know our regional wineries, which are mostly small and enchanting. Remember, though, it is important always to make contact fi rst to arrange your visit. The third and best reason is the wine you will sample during your journeys along the “Wine Routes” of Cyprus. From the traditional indigenous varieties of Mavro (for red and rosé wines) and the white grape Xynisteri, plus the globally unique Koumandaria to well - known global varieties, such as Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz. Let’s take a wine walk. The wine is waiting for us! Vineyard at Lemona 3 route2 Vouni Panagias - Ampelitis Pafos, Mesogi, Tsada, Stroumpi, Polemi, Psathi, Kannaviou, Asprogia, Pano Panagia, Chrysorrogiatissa, Agia Moni, Statos - Agios Fotios, Koilineia, Galataria, Pentalia, Amargeti, Eledio, Agia Varvara or Statos - Agios Fotios, Choulou, Lemona, Kourdaka, Letymvou, Kallepeia Here in this wine region, legend meets reality, as you travel ages old terrain, to encounter the young oenologists making today’s stylish Cyprus wines in 21st century wineries. -

Cyprus Island of Saints

NHSOS KYPROS-Engl.-dec2015:Layout 1 12/20/15 11:20 AM Page 1 Monastery of he Office of the Pilgrimage Tours of the Church Timios Stavros, of Cyprus opens its doors like a big Mansion to Church - - - Limit of area under Turkish Omodos Τwelcome the pilgrim and treat him with the holy of Ieron occupation since 1974 Apostolon, gifts of an entire religious world. Inviting him to experience Pera Chorio in the blessed place of the “Island of Saints”, through travels The Five Domed Church of that are real but also noetic, in everliving spiritual Agioi Varnavas and Ilarionas, landscapes, in the most fascinating geography, in Agios Irakleidios, Peristerona from the Church worshipping places that smell incense and from which Scenes of the Second Coming. Church of Archangelos of Panagia spurt spiritual fragrance. Saints and Donors, view of the Michail, Pedoulas tou Araka, The Virgin Narthex, Church of Panagia tis Lagoudera of Kykkou, Asinou Where Archbishop, Bishops, Abbots, Priests, deacons, hermits, Kykkos monks, church wardens and laics, all those who form the Museum body of the Church of Cyprus, with their spiritual work Stavrovouni Monastery lead the human/pilgrim in a “in spirit and truth” worship. “Monasteries bloom on sheer mountains of the island” In Churches, Monasteries, Cloisters, Ecclesiastical Museums Holy Cross in Omodos where a small piece of the rope and Holy Sacristies that gifted many years ago healing to that the soldiers humans. It is not by chance that pilgrims came from afar to used to bind Monastery be cured of their afflictions and seek solace at the shelter of Christ is kept Monastery of Apostle Andreas of Macheras this holyplace island, in the spiritual glow of Christianity’s temperate clime. -

LCP 2019 Cyprus Workshop Summary

THE LEVANTINE CERAMICS PROJECT 2019 WORKSHOP 2: CERAMIC WARES OF CYPRUS FROM NEOLITHIC THROUGH MEDIEVAL TIMES CAARI & THE CYPRUS MUSEUM, NICOSIA JUNE 13TH-14TH, 2019 WORKSHOP SUMMARY LCP editor Andrea Berlin opened the proceedings with a brief presentation highlighting why it is especially important and useful for archaeologists who work on Cyprus to submit material to the LCP: Cyprus: The rest of the LevaNtine world Needs you!! Archaeologists working elsewhere often identify especially nice (or especially odd) pottery as coming from Cyprus. By adding more vessels (and photos and break photos and thin-sections) to the LCP, you ensure the accuracy of more of those identifications. Currently, there are 9674 vessels on the LCP, of which just 451 (4.6%) are from Cyprus. Come on Cyprus: help the rest of us! The LCP gives you a platform to grapple with – and get a handle on – your pottery, while allowing you to incorporate earlier research. It can help you figure out how to think about your pottery and refine your ideas. It’s also low-stakes: when (not if!) you change your mind, you can edit your entries, add more information, change associations, etc. The LCP can direct other people to your work – and to you! Users may find an example, see a bibliographic citation and/or contributor name – and then click on your name and send an email. The LCP helps us build and expand our scholarly network. The LCP helps you learn about new information quickly. You can set notifications according to frequency (immediately, daily, weekly), mode (by email or by a notice within the site itself), and topic (according to periods, places, and shapes – e.g., only amphoras). -

Authentic Route 8

Cyprus Authentic Route 8 Safety Driving in Cyprus Only Comfort DIGITAL Rural Accommodation Version Tips Useful Information Off the Beaten Track Polis • Steni • Peristerona • Meladeia • Lysos • Stavros tis Psokas • Cedar Valley • Kykkos Monastery • Tsakistra • Kampos • Pano and Kato Pyrgos • Alevga • Pachyammos • Pomos • Nea Dimmata • Polis Route 8 Polis – Steni – Peristerona – Meladeia – Lysos – Stavros tis Psokas – Cedar Valley – Kykkos Monastery – Tsakistra – Kampos – Pano and Kato Pyrgos – Alevga – Pachyammos – Pomos – Nea Dimmata – Polis scale 1:300,000 Mansoura 0 1 2 4 6 8 Kilometers Agios Kato Kokkina Mosfili Theodoros Pyrgos Ammadies Pachyammos Pigenia Pomos Xerovounos Alevga Selladi Pano Agios Nea tou Appi Pyrgos Loutros Dimmata Ioannis Selemani Variseia Agia TILLIRIA Marina Livadi CHRYSOCHOU BAY Gialia Frodisia Argaka Makounta Marion Argaka Kampos Polis Kynousa Neo Chorio Pelathousa Stavros Tsakistra A tis Chrysochou Agios Isidoros Ε4 Psokas K Androlikou Karamoullides A Steni Lysos Goudi Cedar Peristerona Melandra Kykkos M Meladeia Valley Fasli Choli Skoulli Zacharia A Kios Tera Trimithousa Filousa Drouseia Kato Evretou S Mylikouri Ineia Akourdaleia Evretou Loukrounou Sarama Kritou Anadiou Tera Pano Akourdaleia Kato Simou Pano Miliou Kritou Arodes Fyti s Gorge Drymou Pano aka Arodes Lasa Marottou Asprogia Av Giolou Panagia Thrinia Milia Kannaviou Kathikas Pafou Theletra Mamountali Agios Dimitrianos Lapithiou Agia Vretsia Psathi Statos Moni Pegeia - Agios Akoursos Polemi Arminou Pegeia Fotios Koilineia Agios Stroumpi Dam Fountains -

ENGLISH GAZETTE SUMMER 2019.Cdr

PSummer 20R19 OP RTY azette FREE ISSUE “Smell the Sea and feel the sky Let your soul and spirit fly” Van Morisson CONTENTS / WELCOME 3 CONTENTS WELCOME Welcome message Useful contacts 4 An A-Z Guide to the LEPTOS GROUP 6 LEPTOS CALYPSO HOTELS 7 “LEPTOS BLU MARINE” - Investing in Europe's New Riviera 8 NEAPOLIS UNIVERSITY PAFOS 9 NEAPOLIS SMART ECOCITY DEPUTY PRESIDENT 10 EUROPEAN CITIZENSHIP & PERMANENT RESIDENCE 11 NEAPOLIS UNIVERSITY TAKES PART IN PRESTIGIOUS ECONOMIC FORUM Enjoy the bright side of life, in Cyprus! PAPHOS REMAINS THE CHAMPION IN SALES TO OVERSEAS BUYERS AND INVESTORS Dear Friends, PAPHOS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT Cyprus is well known for its high quality of life, mild weather, cultural heritage and 12 IASIS HOSPITAL PAPHOS its recent vibrant economy. The GDP growth rate during the first quarter of 2019 is PROVISION OF GHS SERVICES (Primary medical estimated at 3.5%, with tourism, and real estate driving the economy. According Services) BY THE IASIS PRIVATE HOSPITAL PAPHOS to the United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network report, Cyprus 13 CYPRUS 'FIFTH MOST DESIRABLE DESTINATION has climbed to the top 50 on the list of the world’s happiest countries. FOR BRITS' THIS SUMMER CYPRUS IN TOP 50 OF WORLD'S HAPPIEST COUNTRIES Leptos Estates is a member of the Leptos Group, the leading group in Cyprus in CYPRUS GDP GREW BY 3.5% IN Q1, 2019 the areas of tourism, real estate, with countless international awards. The Leptos MULTI-MILLION MOVIE STARRING NICHOLAS CAGE Group, with almost 60 years of experience, has an outstanding property portfolio TO BE FILMED IN CYPRUS both in Cyprus (Paphos, Limassol, Nicosia), and Greece (Athens, and the islands of Crete, Paros and Santorini). -

Prospectus-Proof-Final-20180628.Pdf

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt as to what action you should take you are recommended to seek your own financial advice immediately from an independent financial adviser who specialises in advising on shares or other securities and who is authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. This document comprises a Prospectus relating to Chesterfield Resources plc prepared in accordance with the Prospectus Rules. This document has been approved by the FCA and has been filed with the FCA in accordance with Rule 3.2 of the Prospectus Rules. The Existing Ordinary Shares are admitted to the Official List (by way of a Standard Listing) and to trading on the London Stock Exchange’s Main Market for listed securities. As the Acquisition represents a Reverse Takeover, upon announcement of the signing of heads of terms in relation to the Acquisition on 2 November 2017, the listing of and trading in the Ordinary Shares was suspended and it is anticipated that, in accordance with the Listing Rules, the existing listing of and trading in the Ordinary Shares will be cancelled. Application has been made to the UK Listing Authority and the London Stock Exchange for all of the ordinary share capital of the Company, issued and to be issued pursuant to the Acquisition, the Placing and the Subscription, to be admitted to the Official List (by way of a Standard Listing) under Chapter 14 of the Listing Rules and to trading on the London Stock Exchange’s Main Market for listed securities. -

Dams of Cyprus

DAMS OF CYPRUS Α/Α NAME YEAR RIVER TYPE HEIGHT CAPACITY (M) (M3) 1 Kouklia 1900 - Earthfill 6 4.545.000 2 Lythrodonta (Lower) 1945 Koutsos (Gialias) Gravity 11 32.000 3 Kalo Chorio (Klirou) 1947 Akaki (Serrachis) Gravity 9 82.000 4 Akrounta 1947 Germasogeia Gravity 7 23.000 5 Galini 1947 Kampos Gravity 11 23.000 6 Petra 1948 Atsas Gravity 9 32.000 7 Petra 1951 Atsas Gravity 9 23.000 8 Lythrodonta (Upper) 1952 Koutsos (Gialias) Gravity 10 32.000 9 Kafizis 1953 Xeros (Morfou) Gravity 23 113.000 10 Agios Loukas 1955 - Earthfill 3 455.000 11 Gypsou 1955 - Earthfill 3 100.000 12 Kantou 1956 Tabakhana Gravity 15 34.000 (Kouris) 13 Pera Pedi 1956 Gravity 22 55.000 14 Pyrgos 1957 Katouris Gravity 22 285.000 15 Trimiklini 1958 Kouris Gravity 33 340.000 16 Prodromos Reservoir 1962 Off - stream Earthfill 10 122.000 17 Morfou 1962 Serrachis Earthfill 13 1.879.000 18 Lefka 1962 Setrachos Gravity 35 368.000 (Marathasa) 19 Kioneli 1962 Almyros Earthfill 15 1.045.000 (Pediaios) 20 Athalassa 1962 Kalogyros Earthfill 18 791.000 (Pediaios) 21 Sotira - (Recharge) 1962 - Earthfill 8 45.000 22 Panagia/Ammochostou 1962 - Earthfill 7 45.000 23 Ag.Georgios - 1962 - Earthfill 6 90.000 (Recharge) 24 KanliKiogiou 1963 Ghinar (Pediaios) Earthfill 19 1.113.000 25 Ammochostou - 1963 - Earthfill 8 165.000 (Recharge) 26 Paralimni - (Recharge) 1963 - Earthfill 5 115.000 27 Agia Napa - (Recharge) 1963 - Earthfill 8 55.000 28 Ammochostou - 1963 - Earthfill 5 50.000 (Antiflood) 29 Argaka 1964 Makounta Rockfill 41 990.000 30 Mia Milia 1964 Simeas Earthfill 22 355.000 31 Ovgos 1964 Ovgos Earthfill 16 845.000 32 Kiti 1964 Tremithos Earthfill 22 1.614.000 33 Agros 1964 Limnatis Earthfill 26 99.000 34 Liopetri 1964 Potamos Earthfill 18 340.000 35 Agios Nikolaos - 1964 - Earthfill 2 1.365.000 (Recharge) 36 Paralimni Lake - 1964 - Earthfill 1 1.365.000 (Recharge) 37 Ag. -

MAP of the QUATERNARY FAULTS of CYPRUS According to Field

STUDY OF ACTIVE TECTONICS IN CYPRUS FOR SEISMIC RISK MITIGATION MANSOURA Sa!! Fs ! T UL A Sa MOSFILERI TILLIRIAS S F MO KATO PYRGOS PO Fs ! MAP OF THE QUATERNARY FAULTS KOKKINA AGIOS THEODOROS TILLIRIAS SC ! OF CYPRUS PACHYAMMOS CHALLERI PIGENIA LIMNITIS SROS !! POMOS AGIO═ GEORGOUDI LT ! FAU IS Fs NIT according to field surveys LIM AMMADIES ALEVGA PANO PYRGOS SR 2001 - 2005 ! SA ! SELEMANI XEROVOUNOS Fs! SA ! LOUTROS GALINI NEA DIMMATA VARISEIA KATO GIALIA CENTRAL MESAORIA NORTH-WESTERN CYPRUS SOUTH-EASTERN CYPRUS AGIA MARINA CHRYSOCHOUS CENTRAL CYPRUS SOUTH-WESTERN CYPRUS LEIVADI Version: Report: Scale: Format: September 14, 2005 GTR/CYP/0905-170 1/ 50 000 A0 3, rue Jean Monnet 34830 Clapiers ^ Tél : (33) 04 67 59 18 11 0 500 1 000 1 500 2 000 Fax : (33) 04 67 59 18 24 Mètres A K ! Be A ! Be M Fp ! A S P E N FS FRODISIA IN ! S U LA ARGAKA SA Legend ! Fs ! OD Faults ! ! FS LOUTRA TIS AFRODITIS Sa ! Fs Quaternary faults PA ! Fp ! ! ! Sa SA !! MAKOUNTA SA SA SC Fault with Quaternary displacement SC ! T L U A ! Sa SC F Inferred fault with Quaternary displacement T A L FS !! D U ! SA N ! Sa A U F LAKKI O G Older fault with Quaternary displacement K A ! N Sa M KAMPOS A L F POLIS Older fault with inferred Quaternary displacement T ! S E DD SA SR KINOUSA W Inferred fault with inferred Quaternary displacement FS !!! DD ! NEON CHORION POLIS DD ! Be PRODROMI Fault scarp, scarplet DD PELATHOUSA TR ! K I ! ### N Faulting within Plio quaternary deposits O Sa TSAKISTRA ! U Sa! S A #### Sa - Reverse fault K FS TR ! A ! ! Be N N *# !( *# A Frontal evidence -

REPUBLIC of CYPRUS Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources And

REPUBLIC OF CYPRUS Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment Geological Survey Department The Preparation of a Strategy for the Restoration of Abandoned Mines FINAL REPORT NOVEMBER 2008 DATE ISSUED: November 2008 JOB NUMBER: OS10047 REPORT NUMBER: J01 FINAL CLIENT’S REFERENCE: 2007/43 REPUBLIC OF CYPRUS; Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment; Geological Survey Department The Preparation of a Strategy for the Restoration of Abandoned Mines PREPARED BY: J S Sceal Consultant (WA) L S Carroll Senior Geologist (WA) H Meddings Environmental Scientist (WA) A Caramondani Town Planner (ALA) A Kalopedis Civil Engineer (ALA) Michael Michael Town and regional Planner (ALA) APPROVED BY: Nick Watson Technical Director This report has been prepared by Wardell Armstrong LLP with all reasonable skill, care and diligence, within the terms of the Contract with the Client. The report is confidential to the Client and Wardell Armstrong LLP accept no responsibility of whatever nature to third parties to whom this report may be made known. No part of this document may be reproduced without the prior written approval of Wardell Armstrong LLP. Republic of Cyprus, Geological Survey Department Study of the restoration of abandoned sulphide mines TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY OF TERMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................. 1 TABLE OF STATUTORY AND LEGISLATIVE MATERIALS .................................................................. 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................................................ -

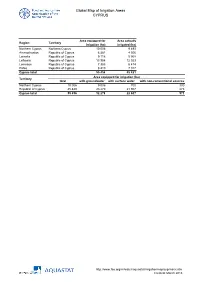

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CYPRUS

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CYPRUS Area equipped for Area actually Region Territory irrigation (ha) irrigated (ha) Northern Cyprus Northern Cyprus 10 006 9 493 Ammochostos Republic of Cyprus 6 581 4 506 Larnaka Republic of Cyprus 9 118 5 908 Lefkosia Republic of Cyprus 13 958 12 023 Lemesos Republic of Cyprus 7 383 6 474 Pafos Republic of Cyprus 8 410 7 017 Cyprus total 55 456 45 421 Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Territory total with groundwater with surface water with non-conventional sources Northern Cyprus 10 006 9 006 700 300 Republic of Cyprus 45 449 23 270 21 907 273 Cyprus total 55 456 32 276 22 607 573 http://www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/irrigationmap/cyp/index.stm Created: March 2013 Global Map of Irrigation Areas CYPRUS Area equipped for District / Municipality Region Territory irrigation (ha) Bogaz Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 82.4 Camlibel Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 302.3 Girne East Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 161.1 Girne West Region Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 457.9 Degirmenlik Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 133.9 Ercan Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 98.9 Guzelyurt Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 6 119.4 Lefke Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 600.9 Lefkosa Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 30.1 Akdogan Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 307.7 Gecitkale Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 71.5 Gonendere Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 45.4 Magosa A Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 436.0 Magosa B Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 52.9 Mehmetcik Magosa Main Region Northern -

Criteria and Indicators for the Sustainable Forest Management in Greece

DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment CRITERIA AND INDICATORS For the Sustainable Forest Management in Cyprus Nicosia Cyprus December, 2006 Contents Page CONTENTS i INTRODUCTION 1 I. Pan-European Quantitative Indicators for SFM CRITERION 1 Maintenance and appropriate enhancement of forest 3 resources and their contribution to global carbon cycles 1.1 Forest Area 3 1.2 Growing Stock 12 1.3 Age Structure and/or Diameter Distribution 15 1.4 Carbon Stock 18 CRITERION 2 Maintenance of forest ecosystem health and vitality 22 2.1 Deposition of Air Pollutants 22 2.2 Soil Condition 27 2.3 Defoliation 30 2.4 Forest Damage 33 CRITERION 3 Maintenance and encouragement of productive 46 functions of forests (wood and non-wood) 3.1 Increment and Fellings 46 3.2 Round-wood 51 3.3 Non-wood Goods 54 3.4 Services 57 3.5 Forests under Management Plans 62 CRITERION 4 Maintenance, conservation and appropriate 64 enhancement of biological diversity in forest ecosystems 4.1 Tree Species Composition 64 4.2 Regeneration 67 4.3 Naturalness 71 4.4 Introduced Tree Species 73 4.5 Deadwood 77 4.6 Genetic Resources 79 4.7 Landscape Pattern 81 4.8 Threatened Forest Species 82 4.9 Protected Forests 87 CRITERION 5 Maintenance and appropriate enhancement of 90 protective functions in forest management (notably soil and water) 5.1 Protective Forests – soil, water and other 89 ecosystem functions 5.2 Protective Forests – infrastructure and 95 managed natural resources CRITERION 6 Maintenance of other socio-economic functions and 96 conditions 6.1 Forest Holdings 96 6.2 Contribution of Forest Sector to GDP 98 i 6.3 Net Revenue 100 6.4 Expenditure for Services 103 6.5 Forest Sector Workforce 105 6.6 Occupational Safety and Health 108 6.7 Wood Consumption 110 6.8 Trade in Wood 112 6.9 Energy from Wood Resources 114 6.10 Accessibility for Recreation 116 6.11 Cultural and Spiritual Values 120 II. -

Determining the Labour-Market Areas of Cyprus from the 2001 Commuting Flows † Pródromos-Ioánnis K

Cyprus Economic Policy Review, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 57-72 (2009) 1450-4561 Determining the Labour-Market Areas of Cyprus from the 2001 Commuting Flows † Pródromos-Ioánnis K. Prodromídis ∗ Centre for Planning and Economic Research [KEPE] Abstract The article utilises the 2001 inter-municipal travel-to-work flows in Cyprus and for the first time delineates the country’s labour market areas (LMAs) on the basis of the 25% commuting threshold (the average used by EU member states in such studies). The findings suggest that the country consists of five economically integrated areas of over 40 thousand inhabitants as well as 26 somewhat isolated clusters of communities or individual communities that collectively host 14 thousand people (2% of the country’s population). Situated on mountainous terrain or along a meandering part of the buffer zone established in the wake of the 1974 Turkish invasion, most of these communities are incorporated into the main LMAs at the (lower) commuting threshold of 20%. The resulting spatial formations bear a rough resemblance to the country’s administrative districts. Overall, the findings enhance our understanding of how the country functions at the sub-national level, which, in turn, permits the formulation of better-targeted economic policy interventions. Keywords: travel-to-work areas, regional and sub-regional economics. JEL-Codes: J49, R12 1. Introduction The purpose of this article is to determine the Labour Market Areas (LMAs) of Cyprus on the basis of disaggregated commuting data solicited in the 2001 Census. As the reader may know, the LMAs are defined as territorial formations (zones) in which the bulk of the economically active or employed resident population work within the same area.