Geology 111 • Discovering Planet Earth • Steven Earle • 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Editorial for Special Issue “Ore Genesis and Metamorphism: Geochemistry, Mineralogy, and Isotopes”

minerals Editorial Editorial for Special Issue “Ore Genesis and Metamorphism: Geochemistry, Mineralogy, and Isotopes” Pavel A. Serov Geological Institute of the Kola Science Centre, Russian Academy of Sciences, 184209 Apatity, Russia; [email protected] Magmatism, ore genesis and metamorphism are commonly associated processes that define fundamental features of the Earth’s crustal evolution from the earliest Precambrian to Phanerozoic. Basically, the need and importance of studying the role of metamorphic processes in formation and transformation of deposits is of great value when discussing the origin of deposits confined to varied geological settings. In synthesis, the signatures imprinted by metamorphic episodes during the evolution largely indicate complicated and multistage patterns of ore-forming processes, as well as the polygenic nature of the mineralization generated by magmatic, postmagmatic, and metamorphic processes. Rapid industrialization and expanding demand for various types of mineral raw ma- terials require increasing rates of mining operations. The current Special Issue is dedicated to the latest achievements in geochemistry, mineralogy, and geochronology of ore and metamorphic complexes, their interrelation, and the potential for further prospecting. The issue contains six practical and theoretical studies that provide for a better understanding of the age and nature of metamorphic and metasomatic transformations, as well as their contribution to mineralization in various geological complexes. The first article, by Jiang et al. [1], reports results of the first mineralogical–geochemical Citation: Serov, P.A. Editorial for studies of gem-quality nephrite from the major Yinggelike deposit (Xinjiang, NW China). Special Issue “Ore Genesis and The authors used a set of advanced analytical techniques, that is, electron probe microanaly- Metamorphism: Geochemistry, sis, X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry Mineralogy, and Isotopes”. -

Microplastics in Beaches of the Baja California Peninsula

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BAJA CALIFORNIA Chemical Sciences and Engineering Department MICROPLASTICS IN BEACHES OF THE BAJA CALIFORNIA PENINSULA TERESITA DE JESUS PIÑON COLIN FERNANDO WAKIDA KUSUNOKI Sixth International Marine Debris Conference SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA, UNITED STATES 7 DE MARZO DEL 2018 OUTLINE OF THE PRESENTATION INTRODUCTION METHODOLOGY RESULTS CONCLUSIONS OBJECTIVE. The aim of this study was to investigate the occurrence and distribution of microplastics in sandy beaches located in the Baja California peninsula. STUDY AREA 1200 km long and around 3000 km of seashore METHODOLOGY SAMPLED BEACHES IN THE BAJA CALIFORNIA PENINSULA • . • 21 sampling sites. • 12 sites located in the Pacific ocean coast. • 9 sites located the Gulf of California coast. • 9 sites classified as urban beaches (U). • 12 sites classified as rural beaches (R). SAMPLING EXTRACTION METHOD BY DENSITY. RESULTS Bahía de los Angeles. MICROPLASTICS ABUNDANCE (R) rural. (U) urban. COMPARISON WITH OTHER PUBLISHED STUDIES Area CONCENTRATIÓN UNIT REFERENCE West coast USA 39-140 (85) Partícles kg-1 Whitmire et al. (2017) (National Parks) United Kigdom 86 Partícles kg-1 Thompson et al. (2004) Mediterranean Sea 76 – 1512 (291) Partícles kg-1 Lots et al. (2017) North Sea 88-164 (190) Particles Kg-1 Lots et al. (2017) Baja California Ocean Pacific 37-312 (179) Particles kg-1 This study Gulf of 16-230 (76) Particles kg-1 This study California MORPHOLOGY OF MICROPLASTICS FOUND 2% 3% 4% 91% Fibres Granules spheres films Fiber color percentages blue Purple black Red green 7% 2% 25% 7% 59% Examples of shapes and colors of the microplastics found PINK FILM CABO SAN LUCAS BEACH POSIBLE POLYAMIDE NYLON TYPE Polyamide nylon type reference (Browne et al., 2011). -

GE OS 1234-101 Historical Geology Lecture Syllabus Instructor

G E OS 1234-101 Historical Geology Lecture Syllabus Instructor: Dr. Jesse Carlucci ([email protected]), (940) 397-4448 Class: MWF, 10am -10:50am, BO 100 Office hours: Bolin Hall 131, MWF, 11am ± 2pm, Tuesday, noon - 2pm. You can arrange to meet with me at any time, by appointment. Textbook: Earth System History by Steven M. Stanley, 3rd edition. I will occasionally post articles and other readings on blackboard. I will also upload Power Point presentations to blackboard before each class, if possible. Course Objectives: Historical Geology provides the student with a comprehensive survey of the history of life, and major events in the physical development of Earth. Most importantly, this class addresses how processes like plate tectonics and climate interact with life, forming an integrated system. The first half of the class focuses on concepts, and the second on a chronologic overview of major biological and physical events in different geologic periods. L E C T UR E SC H E DU L E Aug 27-31: Overview of course; what is science? The Earth as a planet Stanley (pg. 244-247) Sep 5-7: Earth materials, rocks and minerals Stanley (pg. 13-17; 25-34) Sep 10-14: Rocks & minerals continued; plate tectonics. Stanley (pg. 3-12; 35-46; 128-141; 175-186) Sep 17-21: Geological time and dating of the rock record; chemical systems, the climate system through time. Quiz 1 (Sep 19; 5%). Stanley (pg. 187-194; 196-207; 215-223; 232-238) Sep 24-28: Sedimentary environments and life; paleoecology. Stanley (pg. 76-80; 84-96; 99-123) Oct 1-5: Biological evolution and the fossil record. -

Lesson 4: Sediment Deposition and River Structures

LESSON 4: SEDIMENT DEPOSITION AND RIVER STRUCTURES ESSENTIAL QUESTION: What combination of factors both natural and manmade is necessary for healthy river restoration and how does this enhance the sustainability of natural and human communities? GUIDING QUESTION: As rivers age and slow they deposit sediment and form sediment structures, how are sediments and sediment structures important to the river ecosystem? OVERVIEW: The focus of this lesson is the deposition and erosional effects of slow-moving water in low gradient areas. These “mature rivers” with decreasing gradient result in the settling and deposition of sediments and the formation sediment structures. The river’s fast-flowing zone, the thalweg, causes erosion of the river banks forming cliffs called cut-banks. On slower inside turns, sediment is deposited as point-bars. Where the gradient is particularly level, the river will branch into many separate channels that weave in and out, leaving gravel bar islands. Where two meanders meet, the river will straighten, leaving oxbow lakes in the former meander bends. TIME: One class period MATERIALS: . Lesson 4- Sediment Deposition and River Structures.pptx . Lesson 4a- Sediment Deposition and River Structures.pdf . StreamTable.pptx . StreamTable.pdf . Mass Wasting and Flash Floods.pptx . Mass Wasting and Flash Floods.pdf . Stream Table . Sand . Reflection Journal Pages (printable handout) . Vocabulary Notes (printable handout) PROCEDURE: 1. Review Essential Question and introduce Guiding Question. 2. Hand out first Reflection Journal page and have students take a minute to consider and respond to the questions then discuss responses and questions generated. 3. Handout and go over the Vocabulary Notes. Students will define the vocabulary words as they watch the PowerPoint Lesson. -

Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description

Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description Prepared by: Michael A. Kost, Dennis A. Albert, Joshua G. Cohen, Bradford S. Slaughter, Rebecca K. Schillo, Christopher R. Weber, and Kim A. Chapman Michigan Natural Features Inventory P.O. Box 13036 Lansing, MI 48901-3036 For: Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and Forest, Mineral and Fire Management Division September 30, 2007 Report Number 2007-21 Version 1.2 Last Updated: July 9, 2010 Suggested Citation: Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report Number 2007-21, Lansing, MI. 314 pp. Copyright 2007 Michigan State University Board of Trustees. Michigan State University Extension programs and materials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, marital status or family status. Cover photos: Top left, Dry Sand Prairie at Indian Lake, Newaygo County (M. Kost); top right, Limestone Bedrock Lakeshore, Summer Island, Delta County (J. Cohen); lower left, Muskeg, Luce County (J. Cohen); and lower right, Mesic Northern Forest as a matrix natural community, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Ontonagon County (M. Kost). Acknowledgements We thank the Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and Forest, Mineral, and Fire Management Division for funding this effort to classify and describe the natural communities of Michigan. This work relied heavily on data collected by many present and former Michigan Natural Features Inventory (MNFI) field scientists and collaborators, including members of the Michigan Natural Areas Council. -

Sandbridge Beach FONSI

FINDING OF NO SIGNIFICANT IMPACT Issuance of a Negotiated Agreement for Use of Outer Continental Shelf Sand from Sandbridge Shoal in the Sandbridge Beach Erosion Control and Hurricane Protection Project Virginia Beach, Virginia Pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), Council on Environmental Quality regulations implementing NEPA (40 CFR 1500-1508) and Department of the Interior (DOI) regulations implementing NEPA (43 CFR 46), the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) prepared an environmental assessment (EA) to determine whether the issuance of a negotiated agreement for the use of Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) sand from Sandbridge Shoal Borrow Areas A and B for the Sandbridge Beach Erosion Control and Hurricane Protection Project near Virginia Beach, VA would have a significant effect on the human environment and whether an environmental impact statement (EIS) should be prepared. Several NEPA documents evaluating impacts of the project have been previously prepared by both the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and BOEM. The USACE described the affected environment, evaluated potential environmental impacts (initial construction and nourishment events), and considered alternatives to the proposed action in a 2009 EA. This EA was subsequently updated and adopted by BOEM in 2012 in association with the most recent 2013 Sandbridge nourishment effort (BOEM 2012). Prior to this, BOEM (previously Minerals Management Service [MMS]) was a cooperating agency on several EAs for previous projects (MMS 1997; MMS 2001; MMS 2006). This current EA, prepared by BOEM, supplements and summarizes the aforementioned 2012 analysis. BOEM has reviewed all prior analyses, supplemented additional information as needed, and determined that the potential impacts of the current proposed action have been adequately addressed. -

Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods—Roadside Geology

u 0 by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENTOF Natural Resources Jennifer M. Belcher - Commissioner of Public Lands Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor FLOOD BASALTS AND GLACIER FLOODS: Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor Division of Geology and Earth Resources WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Jennifer M. Belcher-Commissio11er of Public Lands Kaleeo Cottingham-Supervisor DMSION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Raymond Lasmanis-State Geologist J. Eric Schuster-Assistant State Geologist William S. Lingley, Jr.-Assistant State Geologist This report is available from: Publications Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources P.O. Box 47007 Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Price $ 3.24 Tax (WA residents only) ~ Total $ 3.50 Mail orders must be prepaid: please add $1.00 to each order for postage and handling. Make checks payable to the Department of Natural Resources. Front Cover: Palouse Falls (56 m high) in the canyon of the Palouse River. Printed oo recycled paper Printed io the United States of America Contents 1 General geology of southeastern Washington 1 Magnetic polarity 2 Geologic time 2 Columbia River Basalt Group 2 Tectonic features 5 Quaternary sedimentation 6 Road log 7 Further reading 7 Acknowledgments 8 Part 1 - Walla Walla to Palouse Falls (69.0 miles) 21 Part 2 - Palouse Falls to Lower Monumental Dam (27.0 miles) 26 Part 3 - Lower Monumental Dam to Ice Harbor Dam (38.7 miles) 33 Part 4 - Ice Harbor Dam to Wallula Gap (26.7 mi les) 38 Part 5 - Wallula Gap to Walla Walla (42.0 miles) 44 References cited ILLUSTRATIONS I Figure 1. -

Lithologic Description Checklist

GY480 Field Geology Lithologic Description Checklist When describing outcrops you should attempt to determine the following at the exposure: 1. Rock name and/or Formation name (Granite, Cap Mt. Limestone member, etc.) 2. Color or color variations at outcrop (pink granite, vari-colored shale, etc.) 3. Mineralogy (estimate percentages if possible; try to distinguish between primary and secondary minerals) 4. texture: size, shape and arrangement of mineral grains (aphanitic, rhyolite porphyry, idioblastic, porphyroblastic, grain-supported, coarse sandstone, foliated granite, etc.). 5. Primary features: crossbeds, ripple marks, sole marks, igneous flow foliation, pillow basalt, vesicular basalt, etc.) Examples of well-written descriptions Sandstone (quartz arenite): white and very pale orange, weathers light brown and moderate reddish brown; very fine grained; subangular; well-sorted; laminated; locally cross-bedded; bedding thickness as much as a foot (30 cm), mostly covered with rubble; forms steep, rounded slope. Bolsa Quartzite. Granite, light gray or light pink, usually deeply weathered to light brown. Typically coarse- grained, containing large phenocrysts of pale-pink orthoclase up to 3 inches (7.6 cm) long. Coarse-grained groundmass consists of pale-pink orthoclase, chalky plagioclase (albite or andesine), quartz, and books of black biotite. Probably underlies diabase and sedimentary formations in most of the region. Ruin Granite. Schist, light to dark gray, weathers brown to greenish-brown. Comprised of a variety of types from coarse-grained quartz-sericite schist to fine-grained quartz-sericite-chlorite schist. Low- grade metamorphism greenschist facies; higher-grade occurs locally. Relict bedding of sedimentary protolith is generally recognizable in outcrop; plunging overturned tight to isoclinal folding is pervasive. -

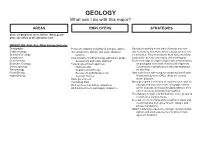

GEOLOGY What Can I Do with This Major?

GEOLOGY What can I do with this major? AREAS EMPLOYERS STRATEGIES Some employment areas follow. Many geolo- gists specialize at the graduate level. ENERGY (Oil, Coal, Gas, Other Energy Sources) Stratigraphy Petroleum industry including oil and gas explora- Geologists working in the area of energy use vari- Sedimentology tion, production, storage and waste disposal ous methods to determine where energy sources are Structural Geology facilities accumulated. They may pursue work tasks including Geophysics Coal industry including mining exploration, grade exploration, well site operations and mudlogging. Geochemistry assessment and waste disposal Seek knowledge in engineering to aid communication, Economic Geology Federal government agencies: as geologists often work closely with engineers. Geomorphology National Labs Coursework in geophysics is also advantageous Paleontology Department of Energy for this field. Fossil Energy Bureau of Land Management Gain experience with computer modeling and Global Hydrogeology Geologic Survey Positioning System (GPS). Both are used to State government locate deposits. Consulting firms Many geologists in this area of expertise work with oil Well services and drilling companies and gas and may work in the geographic areas Oil field machinery and supply companies where deposits are found including offshore sites and in overseas oil-producing countries. This industry is subject to fluctuations, so be prepared to work on a contract basis. Develop excellent writing skills to publish reports and to solicit grants from government, industry and private foundations. Obtain leadership experience through campus organi- zations and work experiences for project man- agement positions. (Geology, Page 2) AREAS EMPLOYERS STRATEGIES ENVIRONMENTAL GEOLOGY Sedimentology Federal government agencies: Geologists in this category may focus on studying, Hydrogeology National Labs protecting and reclaiming the environment. -

On Weathering and Alteration of Rocks

www.rockmass.net On weathering and alteration of rocks Weathering refers to the various processes of physical disintegration and chemical decomposition that occur when rocks at the Earth's surface are subjected to physical, chemical, and biological processes induced or modified by wind, water, and climate. These processes produce soil, unconsolidated rock detritus, and components dissolved in groundwater and runoff. Alteration is a process, which involves changes in the composition of the rock, most often caused by hydrothermal solutions or chemical weathering. Both processes, which generally first affect the walls of the discontinuities, lead to deterioration of the rock material with a reducing effect on its strength and deformation properties, may completely change the mechanical properties and behaviour of rocks. The main results of rock weathering and alteration are: 1. Mechanical disintegration or breakdown, by which the rock loses its coherence, but has little effect upon the change in the composition of the rock material. The results of this process are: The opening up of joints. The formation of new joints by rock fracture, the opening up of grain boundaries. The fracture or cleavage of individual mineral grains. Disintegration involves the breakdown of rock into its constituent minerals or particles with no decay of any rock-forming minerals. The principal sources of physical weathering are thermal expansion and contraction of rock, pressure release upon rock by erosion of overlaying materials, the alternate freezing and thawing of water between cracks and fissures within rock, crystal growth within rock, and the growth of plants and living organisms in rock. Rock alteration usually involves chemical weathering in which the mineral composition of the rock is changed, reorganized, or redistributed. -

Glacial Weathering, Sulfide Oxidation, and Global Carbon Cycle Feedbacks

Glacial weathering, sulfide oxidation, and global carbon cycle feedbacks Mark A. Torresa,b,c,1, Nils Moosdorfa,d,e,1, Jens Hartmannd, Jess F. Adkinsb, and A. Joshua Westa,2 aDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089; bDivision of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125; cDepartment of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, Rice University, Houston, TX 77005; dInstitute for Geology, Center for Earth System Research and Sustainability (CEN), Universität Hamburg, 20146 Hamburg, Germany; and eLeibniz Center for Tropical Marine Research, 28359 Bremen, Germany Edited by Thure E. Cerling, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, and approved July 5, 2017 (received for review February 21, 2017) Connections between glaciation, chemical weathering, and the global erosion (5, 8, 9), which is thought to promote more rapid silicate carbon cycle could steer the evolution of global climate over geologic weathering (10, 11). If glaciation increases erosion rates, and if time, but even the directionality of feedbacks in this system remain to erosion enhances silicate weathering and associated production of be resolved. Here, we assemble a compilation of hydrochemical data alkalinity, then glacial weathering could act as a positive feedback from glacierized catchments, use this data to evaluate the dominant serving to promote further glaciation (5, 12). chemical reactions associated with glacial weathering, and explore the Glaciation may also affect rates of weathering of nonsilicate implications for long-term geochemical cycles. Weathering yields from minerals. Studies of glacial hydrochemistry have pointed to the im- catchments in our compilation are higher than the global average, portance of sulfide oxidation and carbonate dissolution as major which results, in part, from higher runoff in glaciated catchments. -

Metamorphic Rocks (Lab )

Figure 3.12 Igneous Rocks (Lab ) The RockSedimentary Cycle Rocks (Lab ) Metamorphic Rocks (Lab ) Areas of regional metamorphism Compressive Compressive Stress Stress Products of Regional Metamorphism Products of Contact Metamorphism Foliated texture forms Non-foliated texture forms during compression during static pressure Texture Minerals Other Diagnostic Metamorphic Protolith Features Rock Name Non-foliated calcite, dolomite cleavage faces of Marble Limestone calcite usually visible quartz quartz grains are Quartzite Quartz Sandstone intergrown Foliated clay looks like shale but Slate Shale breaks into layers muscovite, biotite very fine-grained, but Phyllite Shale has a sheen like satin muscovite, biotite, minerals are large Schist Shale may have garnet enough to see easily, muscovite and biotite grains are parallel to each other feldspar, biotite, has layers of different Gneiss Any protolith muscovite, quartz, minerals garnet amphibole layered black Amphibolite Basalt or Andesite amphibole grains Texture Minerals Other Diagnostic Metamorphic Protolith Features Rock Name Non-foliated calcite, dolomite cleavage faces of Marble Limestone calcite usually visible quartz quartz grains are Quartzite Quartz Sandstone intergrown Foliated clay looks like shale but Slate Shale breaks into layers muscovite, biotite very fine-grained, but Phyllite Shale has a sheen like satin muscovite, biotite, minerals are large Schist Shale may have garnet enough to see easily, muscovite and biotite grains are parallel to each other feldspar, biotite, has layers of different Gneiss Any protolith muscovite, quartz, minerals garnet amphibole layered black Amphibolite Basalt or Andesite amphibole grains Identification of Metamorphic Rocks 12 samples 7 are metamorphic 5 are igneous or sedimentary Protoliths and Geologic History For 2 of the metamorphic rocks: Match the metamorphic rock to its protolith (both from Part One) Write a short geologic history of the sample 1.