Extract from the Readers'union Magazine, May

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Juniper Hill Conservation Area Appraisal March 2009

Juniper Hill Conservation Area Appraisal March 2009 Planning, Housing and Economy Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Planning Policy Context 4 3. Location and Topography 7 4. History of Kidlington 8 5. CharacterArchitectural area History 11 6. Character of Juniper Hill 13 7. Boundary Justification 17 8. DetailsMaterials & Details 18 9. Historic Photographs 19 10. Management Plan 20 11. ProposedBibliography Extensions and Justification 24 12. BibliographyAppendix 25 13. Appendix List of Figures 1. ConservationLocation Area Boundary 3 2. Area Designations 5 3. Topographical Map 6 4. Aerial View 7 5. DomesdayHistorical maps Book featuring village 9 6. Unlisted1900-06 buildingsMap 12 7. SketchFigure groundMap of planParish 18th century 14 8. VisualMap of Analysis Oxfordshire 1808 16 9. Buildings mentioned in text 10. Listed Buildings 11. Character Areas 12. Areas Proposed for Inclusion in Conservation Area 13. Existing Conservation Area Boundary 14. Proposed Conservation Area Boundary 2 1. Introduction Juniper Hill is a rural hamlet of scattered Juniper Hill was made famous as ‘Lark Rise’ in dwellings situated 7 miles (11.2Km) north of the novels by Flora Thompson which recall her Bicester close to the busy A43. childhood in 1880s rural Oxfordshire. The settlement was first established in the late It is this well documented social history, as 18th century originating with just two cottages well as the evocative nature of the hamlet, in 1754 as an offshoot of nearby Cottisford. which makes Juniper Hill of particular note and The majority of the inhabitants being employed led to its designation as a Conservation Area in local agriculture the population peaked in in 1980. -

Volume 02 Number 09

CAKE AND COCKHORSE Banbury Historical Society September 1964 2s.6d. BAN BURY HI ST OR1 C A L SOCIETY President: The Rt. Hon. Lord Saye and Sele. O.B.E.,M.C., D.L. Chairman: J.H. Fearon, Esq., Fleece Cottage, Bodicote, Banbury. Hon. Secretary Hon. Treasurer: J.S.W. Gibson+ F.S.G.. A.W. Pain, A.L.A. Humber House, c/o Borough Library, Bloxham. Marlborough Road, Banbuy. Banbury. (Tel: Bloxham 332) (Tel: Banbury 2282) Hon. Editor "Cake and Cockhorse": B. S. Trinder, 90 Bretch Hill. Banbury. Hon. Research Adviser: E.R.C. Brinkworth, M. A., F.R. HiSt. SOC. Hon. Archaelogical Adviser: J. H. Fearon, B.SC. Committee Members: Dr. C.F.C. Beeson. D.Sc., R.K. Bigwood. G.J.S. Ellacott, A.C.A. Dr. G.E. Gardam. Dr. H.G. Judge, M.A. *..*....tl The Society was founded in 1958 to encourage interest in the history of the town and neighbour- ing parts of Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire and Warwickshire. The magazine Cake and Cockhorse is issued to members four times a year. This includes illus- trated articles based on original local historical research, as well as recording the Society's activities. A booklet Old Banbury - a short popular history, by E.R.C. Brinkworth, M.A., price 3/6 and a pamphlet A History of Banbury Cross price 6d have been published and a Christmas card is a popular annual production, The Society also publishes an annual records volume. Banbury Marriage Register has been pub- lished in three parts, a volume on Oxfordshire Clockmakers 1400-1850 and South Newin ton Churchwardens' Accounts 1553-1684 have been produced and the Register oduials 'for Banbury covering the years 1558 - 1653 is planned for 1965. -

Lark Rise Observations

1st July, 2008 Issue 21 Oxfordshire Record Office, St Luke’s Church, Temple Road, Cowley, Oxford, OX4 2HT. Telephone 01865 398200. Email [email protected]: www.oxfordshire.gov.uk LARK RISE OBSERVATIONS THE SMITHY AT FRINGFORD Page 1 SEE PAGES 2 and 3 - for ‘Observations’ 1st July, 2008 Issue 21 LARK RISE OBSERVATIONS Anyone watching the recent BBC adaptations of FloraThompson’s Lark Rise to Candleford trilogy will be aware that, although filmed elsewhere, the novels are set in the north-east corner of Oxfordshire with Lark Rise representing Juniper Hill and Candleford supposedly an amalgam of Banbury, Bicester, Brackley and Buckingham. Flora Thompson (nee Timms) lived at End House in Juniper Hill, a hamlet of Cottisford where she attended the local Board school and church on Sundays. Her job in the post office was at Fringford (about 4-5 miles away). In the novels Flora called herself Laura and in the TV series her parents are called Robert and Emma Timmins. In real life her family name was Timms and her parents were called Albert and Emma. The End House where they lived in Juniper Hill can still be seen today (part of a modern dwelling) and its location can be seen on an OS map, c1900. The Cottisford parish registers reveal that 10 children of Albert and Emma were baptized in the church, starting with Martha on 13th Nov 1875 and ending with Cecil Barrie on 6th Mar 1898 (over 20 years, by which time Emma was in her mid-40s). Four of the children, including Martha, Albert (born 1882), Ellen Mary (born 1893) and Cecil Barrie (buried 4th Apr 1900) died in infancy. -

Flora Thompson Report Commemorating Flora's Life

FLORA THOMPSON REPORT COMMEMORATING FLORA’S LIFE 70 YEARS AFTER HER DEATH The ‘Evening at Lark Rise’ special evening event on June 28 last, the main focus of the Old Gaol’s Commemoration of Flora Thompson’s life 70 years after her death, was very well attended by over thirty five visitors (plus invited guests), who thoroughly enjoyed both the current standing commemorative exhibition (on until July 5) and the ‘Evening at Lark Rise’ special event, itself. The main thrust of the actual Flora Thompson commemorative exhibition in the Old Gaol exercise yard, held from June 23 to July 5, is to showcase items and memorabilia, including some rare and scarcely seen items, some over 100 years old, and others, although completely complementary to the Flora Thompson story and her life and works, rarely see the light of day. Others, particularly the commemorative china and metal items of the early and mid eighties, although produced in fairly large numbers, are also largely unknown to the general public, even to many Flora aficionados themselves. TO PICK OUT SOME OF THE MORE UNUSUAL ITEMS: The Catholic Fireside Magazine – a bound copy of twelve editions of this periodical each containing work by Flora Thompson, dated July to September 1925. A feature about Flora Thompson (‘poetess’ [sic]) in the Daily Page 15 Mirror dated 3 March 1921. A selection from a collection of over 50 theatre programmes from theatres in all parts of the country, from Buckingham to London, Nottingham to Southampton, and all parts between. A rare copy of ‘Fifty-One Poems’ by Mary Webb (the author of ‘Precious Bane’), signed and inscribed to Winifred Thompson (Flora’s daughter), by the illustrator (and well known wood cut engraver of the time), Joan Hassall. -

April 2016 Tadley and District History Society (TADS)

April 2016 Tadley and District History Society (TADS) - www.tadshistory.com Next meeting - Wednesday 20th April 2016 at St. Paul’s Church Hall, 8.00 to 9.30pm ‘The Great Exhibition of 1851’ By Rosina Brandham (Everybody welcome - visitors £2.50) Committee Notes Programme Secretary - We are very pleased that Jim West has volunteered to take on the role of organising the Programme. So TADS will continue. Membership - it is still cheaper to become a member than pay as a visitor at each meeting. Comments, queries and suggestions to Richard Brown (0118) 9700100, e-mail: [email protected] or Carol Stevens (0118) 9701578 www.tadshistory.com TADS Meeting 18th May 2016 ‘The Benedictine Way of Life’ By Reg Fletcher TADS Meeting 16th March 2016 Flora Thompson – beyond Candleford by John Owen-Smith Scintillating speaker and author, John talked to us, with the spark and energy of a lively terrier, of sometime postal assistant, then postmistress and author, Flora Thompson (1878-1947). Flora was something of an enigma during her life. Still is. Maybe at the turn of the 20th Century, life for a woman was more difficult and often subsumed by a picky publisher or a strict husband. Or both. Possibly Flora's book 'Larkrise to Candleford' appeals to the gals because of the frock-fest and vulnerable children and the guys because of the bucolic, clay ruralness of the NE Oxfordshire/Northhamptonshire and Buckinghamshire borders. Candleford may be modelled on the Buckingham of the day. Flora wasn't a particularly famous or prolific writer, only taking up writing in her sixties. -

History Society Meeting No 19

MINUTES OF THE 19th MEETING OF AYNHO HISTORY SOCIETY HELD AT AYNHO VILLAGE HALL ON WEDNESDAY 27TH MAY 2009 Present: – Brian Reynolds - Chairman Peter Cole – Secretary. At least 42 other members and guests attended. 1 Correspondence The secretary had received no correspondence this month. 2 Chair and Finance Report There is £787.28 in the bank account. We will be attending the Brackley History Society Exhibition on June 6th at Brackley Town Hall, with a display of artefacts, and possibly some armaments. We shall also have a stand at the Church Fete the following Saturday June 13th in Aynhoe Park. The Cartwright Arms pub sign is now in our possession. Robin Cox is removing the steelwork so that we can easily display the sign. It was suggested that subject to the approval of the Village Hall Committee, it should be displayed on the wall there. This was agreed. It was also agreed that Robin Cox could have the steelwork. Brian proposed that the annual student membership of Aynho History Society should be £1, and 50p per meeting. This was seconded by Jean Darby and agreed. 3. Iford Manor & Peto Garden Tuesday 6th October 2009 The coach for this trip is almost full already, so anyone else wishing to go should let Brian know as soon as possible. Brian also mentioned that Rightracks survey forms are available for anyone to complete and return to the Clerk as soon as possible. 4. Aynho Tunnels Project Update Brian Reynolds Brian said that Wendy Morrison is double-booked for tonight and sends her apologies. -

Shelswell News the Magazine of the Shelswell Group of Churches

Shelswell News The magazine of the Shelswell Group of Churches Cottisford Finmere Fringford Godington Hardwick Hethe Mixbury Newton Purcell Stoke Lyne Stratton Audley St Michael and All Angels, Fringford We celebrate the Feast of St Michael & All Angels (Michaelmas) on 29th September September 2021 £1 2 SHELSWELL BENEFICE MISSION STATEMENT The Shelswell Family of Churches aims to bring people closer to God and to show the love of Jesus Christ and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit to everyone. MINISTRY TEAM RECTOR: The Reverend Alice Goodall, The Rectory, Water Stratford Road, Finmere, Buckingham MK18 4AT Telephone: 01280 848192 Email [email protected] (Normal day off – Friday) BENEFICE ADMINISTRATOR: Mrs Becky Adams, c/o The Rectory (as above) Email [email protected] Administrator’s normal office hours: Tuesday, Thursday and Friday 9.00 am – 1.00 pm CURATE: Revd Yvonne Mullins, 10c St Michael’s Close, Fringford, Bicester OX27 8DF Telephone 01869 278090 Email [email protected] ASSOCIATE MINISTER: The Reverend Liz Welters, 19 Scampton Close, Bicester OX26 4FF Telephone 01869 249481 Email [email protected] LICENSED LAY MINISTER: Mrs Penny Wood, 8 Crosslands Fringford, Bicester, Oxon. OX27 8DF Telephone: 01869 277310 Email [email protected] THE PARISHES ARE PART OF THE DEANERY OF BICESTER AND ISLIP AND THE DORCHESTER EPISCOPAL AREA OF THE DIOCESE OF OXFORD HOLY TRINITY ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH, HETHE, Mass: 8 am on Sunday. Occasional 12 noon Traditional Latin Mass. Weekday Mass: 9.30 am Monday and Friday Priest: Very Rev. Canon John Batthula, Henley House, 12 The Causeway, Bicester, OX26 6AW. Telephone: 01869 253277 Website: http://www.holytrinityhethe.co.uk/ SHELSWELL NEWS Published monthly. -

Press Release

Press Information finboroughtheatre Shapeshifter, Berwick House Productions and Concordance present Lark Rise to Candleford by Keith Dewhurst, from the books by Flora Thompson Directed by John Terry and Mike Bartlett. Designed by Alex Marker. New musical arrangements by Tim van Eyken. Movement by Kitty Winter. Costumes by Penn O’Gara. Cast includes: David Brett. Hugo Cox. Rosalind Cressy. Hannah Emanuel. Susie Emmett. Nicky Goldie. Michael Lovatt. Gary Mackay. Tom Murphy. Owyn Stephens. Anna Tolputt. Sophie Trott. TWO PROMENADE PLAYS IN REPERTOIRE! THE FIRST REVIVAL OF BOTH PLAYS SINCE THE ORIGINAL NATIONAL THEATRE PRODUCTION WINNER OF THE PETER BROOK EMPTY SPACE MARK MARVIN AWARD “As she went on her way, gossamer threads, spun from bush to bush, barricaded her pathway, and as she broke through one after another of these fairy barricades she thought, “They’re trying to bind and keep me.” But the threads which were to bind her to her native county were more enduring than gossamer. They were spun of love and kinship and cherished memories.” Lark Rise to Candleford is a lively two-play adaptation for the theatre of Flora Thompson’s classic trilogy of Oxfordshire life at the end of the 19th century, recalling an era when the traditional ways and values of rural society were disappearing beneath the clamour of modern life and finally vanishing forever in the carnage of the First World War. The two plays can be seen in any order, separately or together. Shapeshifter’s dynamic promenade staging, featuring extensive live folk music, immerses the audience in the forgotten communities of a vanishing England. -

The Following Have Kindly Sponsored the Cost Of

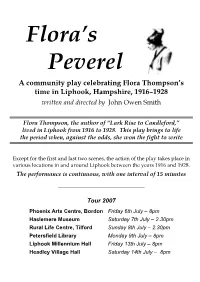

Flora’s Peverel A community play celebrating Flora Thompson’s time in Liphook, Hampshire, 1916–1928 written and directed by John Owen Smith Flora Thompson, the author of “Lark Rise to Candleford,” lived in Liphook from 1916 to 1928. This play brings to life the period when, against the odds, she won the fight to write Except for the first and last two scenes, the action of the play takes place in various locations in and around Liphook between the years 1916 and 1928. The performance is continuous, with one interval of 15 minutes Tour 2007 Phoenix Arts Centre, Bordon Friday 6th July – 8pm Haslemere Museum Saturday 7th July – 2.30pm Rural Life Centre, Tilford Sunday 8th July – 2.30pm Petersfield Library Monday 9th July – 8pm Liphook Millennium Hall Friday 13th July – 8pm Headley Village Hall Saturday 14th July – 8pm CAST – in order of appearance Flora Thompson ................................................................................................ Mel White Postman at Bournemouth ....................................................................... John McGregor ‘Louie’ Woods ............................................................................................. Georgia Keen Sgt John Mumford ............................................................................. Charlie O’Reardon John Thompson ................................................................................................. Rod Sharp ‘Joe’ Leggett (at 8 years old) ........................................................................... Alex Clark -

Cake & Cockhorse

CAKE & COCKHORSE BANBURY EIISTORICAL SOCIETY AUTUMN 1914 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY President : The Lord Saye and Sele Chairman: J. F. Roberts, The Old Rectory, Broughton Road, Banbury (Tel: Banbury 1 Magazine Editor: J. B. Barbour, M.A. PhD, College Farm, South Newington, Banbury (Tel; Banbury 720492) Hon. Secretary: Assistant Secretary Hon. Treasurer: Miss C. G. Bloxham, B. A. and Records Series Editor: Dr. G. E. Gardam c/o Oxford City and County Museum 11 Denbigh Close Fletcher's House, J.S.W. Gibson, F.S.A. Broughton Road Woodstock, 11 Westgate Banbury OX16 OBQ Oxford Chichester PO19 3ET (Tel: Banbury 2841) (Tel: Woodstock 811456) (Tel: Chichester 84048) Hon. Research Adviser: Hon. Archaeological Adviser: E.R.C. Brinkworth, M.A., F.R.Hist.S. J.H. Fearon, B.Sc. Committee Members Krs J. W. Brinkworth, Miss N. M. Clifton, Mr A. Donaldson, Miss F. M. Stanton The Society was founded in 1957 to encourage interest in the history of the town of Banbury and neighbouring parts of Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire and Warwickshire. The Magazine Cake & Cockhorse is issued to members three times a year. This includes illustrated articles based on original local historical research, as well as recording the Society's activities. Publications include Old Banbury - a short popular history by E. R. C. Brinkworth (2nd edition), New Light on Banbury's Crosses, Roman Banburyshire, Banbury's Poor in 1850, Banbury Castle - a summary of excavations in 1972, The Building and Furnishing of St Mary's Church, Banbury, and Sanderson Miller d Badway and his work at Wroxton, and a pamphlet History d Banbury Cross. -

Larkwell Juniper Hill • Northamptonshire

LARKWELL JUNIPER HILL • NORTHAMPTONSHIRE LARKWELL Juniper Hill • Northamptonshire Character property surrounded by gardens of 1.2 acres Distances Approximate: • Brackley 3 miles • Buckingham 9 miles • Bicester 8 miles (Bicester North/London Marylebone about 50 mins) • Milton Keynes 22 miles (Milton keyns to London Euston about 35 mins) • Oxford 20 miles Accommodation: • Reception hall • Kitchen/breakfast room • Utility room • Dining room and snug • Sitting room • Study • Cloakroom • Four bedrooms (one en suite) • Family bathroom • Double garage • Gardens • Off road parking In all about 1.2 acres EPC=E YOUR ATTENTION IS DRAWN TO THE IMPORTANT NOTICE ATTACHED TO THESE SALE PARTICULARS. family space. The study has built in book the A43 taking the first turning off to the left sign shelves with views of the gardens. There is an posted Juniper Hill. On entering the village the inner hall with parquet flooring, cloakroom property is the first house on the left. and original front door with porch to the front SERVICES of the property. Mains electricity and water are connected to the • Sitting room with three aspects has views property, oil fired central heating. of the gardens with open fire place and glass French doors leading out onto the LOCAL AUTHORITIES patio garden. Cherwell District Council Tel:01295 250723 • The first floor has master bedroom with COUNCIL TAX BAND F en suite bathroom and built in cupboards. There are three further generous sized POSTCODE: NN13 5RH bedrooms and family bathroom. TENURE: FREEHOLD OUTSIDE VIEWINGS To the front of the house is a traditional cottage Strictly by appointment with Savills. If there garden enclosed by a stone wall with access is any point which is of particular importance to through a pedestrian gate onto the drive which you, we invite you to discuss this with wraps alongside the house leading to a parking us, especially before you travel to view Bicester North to London Marylebone from SITUATION area with hard standing for several cars. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Over to Candleford by Flora Thompson Download Now! We Have Made It Easy for You to Find a PDF Ebooks Without Any Digging

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Over to Candleford by Flora Thompson Download Now! We have made it easy for you to find a PDF Ebooks without any digging. And by having access to our ebooks online or by storing it on your computer, you have convenient answers with Lark Rise To Candleford Flora Thompson . To get started finding Lark Rise To Candleford Flora Thompson , you are right to find our website which has a comprehensive collection of manuals listed. Our library is the biggest of these that have literally hundreds of thousands of different products represented. Finally I get this ebook, thanks for all these Lark Rise To Candleford Flora Thompson I can get now! cooool I am so happy xD. I did not think that this would work, my best friend showed me this website, and it does! I get my most wanted eBook. wtf this great ebook for free?! My friends are so mad that they do not know how I have all the high quality ebook which they do not! It's very easy to get quality ebooks ;) so many fake sites. this is the first one which worked! Many thanks. wtffff i do not understand this! Just select your click then download button, and complete an offer to start downloading the ebook. If there is a survey it only takes 5 minutes, try any survey which works for you. ISBN 13: 9780141190150. In the little hamlet of Lark Rise times are changing and Laura is growing up. Although she must attend the nearby village school, she would far rather read and make up stories in her head.