Discworld and the Disciplines: Critical Approaches to the Terry Pratchett Works Eds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Models of Time Travel

MODELS OF TIME TRAVEL A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING FILMS Guy Roland Micklethwait A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2012 National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science ANU College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences APPENDIX I: FILMS REVIEWED Each of the following film reviews has been reduced to two pages. The first page of each of each review is objective; it includes factual information about the film and a synopsis not of the plot, but of how temporal phenomena were treated in the plot. The second page of the review is subjective; it includes the genre where I placed the film, my general comments and then a brief discussion about which model of time I felt was being used and why. It finishes with a diagrammatic representation of the timeline used in the film. Note that if a film has only one diagram, it is because the different journeys are using the same model of time in the same way. Sometimes several journeys are made. The present moment on any timeline is always taken at the start point of the first time travel journey, which is placed at the origin of the graph. The blue lines with arrows show where the time traveller’s trip began and ended. They can also be used to show how information is transmitted from one point on the timeline to another. When choosing a model of time for a particular film, I am not looking at what happened in the plot, but rather the type of timeline used in the film to describe the possible outcomes, as opposed to what happened. -

Visual Representations of Terry Pratchett's Discworld in Time And

IMAGINATIONS: JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL IMAGE STUDIES | REVUE D’ÉTUDES INTERCULTURELLES DE L’IMAGE Publication details, including open access policy and instructions for contributors: http://imaginations.glendon.yorku.ca Visibility and Translation Guest Editor: Angela Kölling December 31, 2020 Image Credit: Cia Rinne, Das Erhabene (2011) To cite this article: Sohár, Anikó. “Each to Their Own: Visual Representations of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld in Time and Space.” Imaginations: Journal of Cross-Cultural Image Studies, vol. 11, no. 3, Dec. 2020, pp. 123-163, doi: 10.17742/IMAGE.VT.11.3.6. To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.17742/IMAGE.VT.11.3.6 The copyright for each article belongs to the author and has been published in this journal under a Creative Commons 4.0 International Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives license that allows others to share for non-commercial purposes the work with an acknowledgement of the work’s authorship and initial publication in this journal. The content of this article represents the author’s original work and any third-party content, either image or text, has been included under the Fair Dealing exception in the Canadian Copyright Act, or the author has provided the required publication permissions. Certain works referenced herein may be separately licensed, or the author has exercised their right to fair dealing under the Canadian Copyright Act. EACH TO THEIR OWN: VISUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF TERRY PRATCHETT’S DISCWORLD IN TIME AND SPACE ANIKÓ SOHÁR When a book is translated, publishers Lorsqu’un livre est traduit, les éditeurs mo- will often modify or completely change difient souvent, voire changent complète- the cover design. -

Hogfather: a Novel of Discworld by Terry Pratchett

Hogfather: A Novel of Discworld by Terry Pratchett Ebook Hogfather: A Novel of Discworld currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Hogfather: A Novel of Discworld please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download book here >> Series: Discworld (Book 20) Mass Market Paperback: 416 pages Publisher: Harper; Reissue edition (January 28, 2014) Language: English ISBN-10: 006227628X ISBN-13: 978-0062276285 Product Dimensions:4.2 x 0.9 x 7.5 inches ISBN10 ISBN13 Download here >> Description: Who would want to harm Discworlds most beloved icon? Very few things are held sacred in this twisted, corrupt, heartless—and oddly familiar— universe, but the Hogfather is one of them. Yet here it is, Hogswatchnight, that most joyous and acquisitive of times, and the jolly, old, red-suited gift-giver has vanished without a trace. And theres something shady going on involving an uncommonly psychotic member of the Assassins Guild and certain representatives of Ankh-Morporks rather extensive criminal element. Suddenly Discworlds entire myth system is unraveling at an alarming rate. Drastic measures must be taken, which is why Death himself is taking up the reins of the fat mans vacated sleigh . which, in turn, has Deaths level-headed granddaughter, Susan, racing to unravel the nasty, humbuggian mess before the holiday season goes straight to hell and takes everyone along with it. Terry Pratchett was brilliant and the master of a fantasy sub-genre that probably belongs to him alone. Mort is a novel set in Discworld. The Discworld novels fall into different categories: Tiffany Aching, Rincewind, the three witches, Sam Vines and the guards, and Death. -

Sfrareview in This Issue 312 Spring 2015

312 Spring 2015 Editor Chris Pak SFRA University of Lancaster, Bailrigg, Lan- A publicationRe of the Scienceview Fiction Research Association caster LA1 4YW. [email protected] Managing Editor In this issue Lars Schmeink Universität Hamburg, Institut für Anglis- SFRA Review Business tik und Amerikanistik, Von Melle Park 6 Gearing Up ............................................................................................................2 20146 Hamburg. W. [email protected] SFRA Business Nonfiction Editor #SFRA2015 ............................................................................................................2 Dominick Grace Live Long and Prosper .........................................................................................3 Brescia University College, 1285 Western Sideways in Time [conference report] ..............................................................3 Rd, London ON, N6G 3R4, Canada phone: 519-432-8353 ext. 28244. BSLS: British Society for Literature and Science [conference report] ..........5 [email protected] Feature 101 Assistant Nonfiction Editor Teaching Science Fiction .....................................................................................7 Kevin Pinkham College of Arts and Sciences, Nyack To Bottom Out: An Incomplete Guide to the New Venezuelan SF ............14 College, 1 South Boulevard, Nyack, NY 10960, phone: 845-675-4526845-675- 4526. Nonfiction Reviews [email protected] The American Shore: Meditations on a Tale of Science Fiction by Thomas M. Disch -

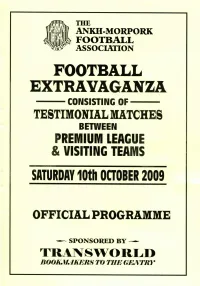

Event Programme

THE ANKH-MORPORK FOOTBAJLL ASSOCIATION FOOTBALL EXTRAVAGANZA CONSISTING OF TESTIMONIAL MATCHES BETWEEN PREMIUM LEAGUE & VISITING TEAMS SATURDAY 10th OaOBER 2009 OFFICIAL PROGRAMME ^ SPONSORED BY TRAJVSWORLD BOOKAMKEltS TO THE GEJVTRY THE ANKH-MORPORK TIME TABLE FOOTBALL SATURDAY 10th Subject to any alteration, at any time. ASSOCIATION ASSEMBLE IN OaOBER 2009 THE SPORTS GROUND FROM 11AM At about NOON A WELCOME ADDRESS BY THE MANAGEMENT & TRAINERS OF TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS, WHO ARE TODAY'S HOSTS. ' A day that Teams will ussemble and he checked by Officials of the will go down in A-M F^\.for weapons, foodstuffs, bottles, or other Football History, impediment to fair play. i A day that when in your Note: dotage; or next week, No Linesmen or Referee us to be offered any bribe or whenever is sooner, you inducement to influence the performance of their duties in ean show your sears and a fair ami impartial manner. say "1 was there," "I ate the pies, I turned TEAMS WILL ASSEMBLE up, paid up and played FOR THE ORGANISERS TO ALLOCATE BY the game". A DRAW BETWEEN ALL TEAMS PRESENT, From all over the eountry and beyond, young men PITCH NUMBER AND KICK-OFF TIMES and women answered the call. Joined the eolours, ROUND 1. and made for one day a THE MATCHES WILL sleepy town in Somerset the huh of football KICK-OFF prowess. They came because a man ROUND 2. wrote a book. They came THE WINNING TE^VMS (SURATVORS) because his publishers* WILL THEN PLAY offered free beer. They came to make history. ROUND 3 That man was, SIR TERRY PR.\TCHETT THE FINAL And the book was, THERE WILL BE A CUP. -

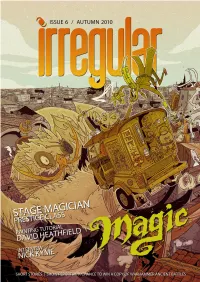

Issue 6 2010.Indb

Editorial Nick Johnson & Jason Hubbard 3 Skirmish Painting Competition Results 4 Painting Competition 6 Stage Magician Prestige Class Dave Barker 7 Wizard Illustration Ricardo Guimaraes 11 Tuk Tuk Will Kirkby 12 Iron, Steam & Really Short People Part 2 Nick Johnson 14 Meet the Mages of Middle Earth David Kay 23 The Death of Magic Richard Tinsley 25 Homecoming Taylor Holloway 28 Didn’t We Have a Lovely time the Day We William Ford 34 Went to Sheffield A Drink with Nick Kyme Peter Allison 36 Artist Showcase Diego de Almeida 39 Euro Militaire 2010 Jason Hubbard 44 Sheffield Kotei 2010 Jim Freeman 46 A Gaming Group’s Adventure GD USA Mike Schaeffer 50 Games Day UK Jason Hubbard 54 The Application of Paint David Heathfield 56 Flora Basing Brett Johnson & Rebecca Hubbard 64 Sculpting Robes in Greenstuff Richard Sweet 66 A Step by Step; Nanny Ogg Mike Dodds 68 Gradients Rebecca Hubbard 72 Discworld miniature Review Various 75 Hearts & Minds: Flying Lead Supplement Dave Barker 80 Britanan Grenadiers & Troopers Peter Scholey 81 Hammer’s Slammers Dave Barker 82 Fields of Glory: Renaissance Nick Slonskyj 83 28mm Sandbag Emplacement Peter Scholey 85 Cornelius the Wizard Rebecca Hubbard 86 WW2 German Infantry Jason Hubbard 87 2 Editors Jason Hubbard Nick Johnson Layout Jason Hubbard Jason: Well folks, it seems it’s that time again - another issue of Irregular Magazine is on the virtual shelf, and what a jam-packed issue we have for you all. We have an- Proof Reader other another supplement, though I let Nick discuss that particular goody, as he was Nick Johnson involved in the writing of it. -

Tiffany Aching, Hermione Granger, and Gendered Magic in Discworld and Potterworld

Volume 27 Number 3 Article 16 4-15-2009 The Education of a Witch: Tiffany Aching, Hermione Granger, and Gendered Magic in Discworld and Potterworld Janet Brennan Croft University of Oklahoma Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Croft, Janet Brennan (2009) "The Education of a Witch: Tiffany Aching, Hermione Granger, and Gendered Magic in Discworld and Potterworld," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 27 : No. 3 , Article 16. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol27/iss3/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Explores the depiction of gender in education, and how gender issues in education relate to power and agency, in two current young adult fantasy series featuring feisty heroines determined to learn all that they can: Hermione Granger in J.K. -

Terry Pratchett -A (Disc) World of Collecting

TERRY PRATCHETT -A (DISC) WORLD OF COLLECTING Colin Steele Background Terrence David John Pratchett - Terry Pratchett - is the author of the phenomenally successful Discworld series and is one of contemporary fiction’s most popular writers. Since Nielsen's records began in 1998, Pratchett has sold around 10 million books in the UK, generating more than £70 million in revenue. His agent and original publisher, Colin Smythe says Pratchett has either written, co-written or been creatively associated with 100-plus books, notably Discworld titles, Despite this prodigious output, Pratchett is one of the UK’s most collectable authors, particularly for his early books and special editions. Pratchett‘s first book, The Carpet People, was published in 1971, while his first Discworld novel, The Colour of Magic, appeared in 1983. 36 more Discworld books have followed, many of which have topped the UK hardback and paperback lists. Pratchett's novels have sold more than 60 million copies and have been translated into 33 languages Until Pratchett’s recent diagnosis of an early stage of a rare form of Alzheimer’s disease, he usually wrote two books a year, which reputedly earned him £1 million each. When asked “What do you love most about your job? “ Pratchett replied “Well, I get paid shitloads of cash...which is good”. Pratchett donated £500,000 towards Alzheimer’s research in March 2008. Pratchett anticipates dictating novels from 2009 onwards due to his illness. He recently told the BBC, that compared to his once rapid typing, that he now types “badly - if it wasn’t for my loss of typing ability, I might doubt the fact that I have Alzheimer’s. -

The Witches: a Discworld Game Rulebook

THE WITCHES ‘The Witches’ game draws on some of the characters and situations described in Terry Pratchett’s Discworld® books. In the game you take on the part of a young trainee witch such as Tiffany Aching or Petulia Gristle. You have been dispatched to Lancre to improve your craft, which seems to be a case of learning on the job. Being a witch means solving other peoples’ problems. One day you will be curing a sick pig or fixing a broken leg. On other occasions it will mean fighting back an invasion of elves or dealing with the Wintersmith. It very much depends which day of the week it is. In essence this is an adventure game. As a trainee witch you Players must be careful to not let too many crisis situations move around the board attempting to solve problems which build up, as if they do the game will end quickly, resulting in come in two types, easy ones and hard ones. At first you should everybody losing. stick to attempting to solve easy problems as doing so will ‘The Witches’ is a game for one to four players and should increase the number of cards you hold, making you stronger. take around ninety minutes. Please do not be daunted by the At some point you will be able to take on hard problems. All number of pages of rules in the game. The game itself is not problems are solved in the same way, you roll the dice and see too complicated, but there are a number of situations that may if you reach the required total. -

Fahrenheit 451

FAHRENHEIT 451: A DESCRIPTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY Amanda Kay Barrett Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of English, Indiana University May 2011 Accepted by the Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. __________________________________________ Jonathan R. Eller, Ph.D., Chair Master’s Thesis Committee __________________________________________ William F. Touponce, Ph.D. __________________________________________ M. A. Coleman, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my wonderful thesis committee, especially Dr. Jonathan Eller who guided me step by step through the writing and editing of this thesis. To my family and friends for encouraging me and supporting me during the long days of typing, reading and editing. Special thanks to my mother, for being my rock and my role model. To the entire English department at IUPUI – I have enjoyed all these years in your hands and look forward to being a loyal and enthusiastic alumna. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Narrative Introduction ..........................................................................................................1 Genealogical Table of Contents .........................................................................................17 Fahrenheit 451: A Descriptive Bibliography .....................................................................24 Primary Bibliography.........................................................................................................91 -

Ankh-Morpork: the City As Protagonist

Ankh-Morpork: The City as Protagonist Anikó Sóhar Université Catholique Pázmány Péter Abstract: In science fiction and fantasy, sometimes the city (whether it is real or imaginary) plays the leading role, for example New York in Winter’s Tale by Mark Helprin, or London in Neverwhere by Neil Gaiman. Often, as in the case of Newford in several novels and short stories by Charles de Lint, a made-up city with its fictional topography and maps corresponds to and accentuates the social relations as well as the emotions embedded in the narration; the geography can indeed be emotional as it was so aptly put by Sir Terry Pratchett when he appointed Rincewind (one of his regularly popping-up characters) “Egregious Professor of Cruel and Unusual Geography of Unseen University” (among other jobs). Sir Terry also dreamt up a very significant city called Ankh-Morpork in his Discworld series (which might have been based on Budapest) which offers a perfect topic for discussion. Ankh-Morpork, which was a simple although very funny parody of a typical city in fantasy fiction at the beginning, gradually becomes a setting for emancipation, liberation and disenthralment from various bonds, and provides ample examples of references to British and internationalised culture. The city itself does not play a leading role in any of the novels, but when the whole series is taken into consideration, its significance is immediately apparent, the whole series forms a sort of bildungsroman which describes the maturation process of Ankh-Morpork. The whole sensational landscape created for our amusement as well as intellectual and moral benefit could be accurately mapped in terms of literary-cum-urban-studies, geopoetics, focusing on several aspects of social criticism. -

Masaryk University

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English Language and Literature Translation of Names and Proper Names in Terry Pratchett’s works from Discworld Stanislav Chvíla Bachelor Thesis Brno 2017 Supervisor: Mgr. Martin Němec, Ph.D. Declaration Hereby I declare that I worked on this Bachelor thesis on my own, using only the sources listed in the bibliography. I agree with the deposition of my thesis in the library of the Faculty of Education at the Masaryk University where it will be available for further academic purposes. Prohlášení Tímto prohlašuji, že svou bakalářskou práci jsem vypracoval samostatně, s použitím pouze citovaných literárních pramenů, dalších informací a zdrojů v souladu s Disciplinárním řádem pro studenty Pedagogické fakulty Masarykovy univerzity a se zákonem č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů (autorský zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů. Souhlasím s tím, aby moje práce byla uložena na Masarykově Univerzitě v Brně v knihovně pedagogické fakulty k dalším studijním účelům Brno, 26th March, 2017 Stanislav Chvíla Anotace V této bakalářské práci je představen alternativní překlad vlastních jmen a názvů z anglického jazyka do českého v dílech Terryho Pratchetta ze světa Zeměplochy za použití tradičních překladatelských postupů. Bakalářská práce je rozdělena na 2 hlavní části. V první, úvodní části, je představen autor Zeměplochy Terry Pratchett, Jan Kantůrek – autor jediného českého překladu, a také samotný svět Zeměplochy. Následuje obeznámení se základními teoriemi překladu. Druhá, praktická část, je tvořena návrhem alternativního překladu jména postavy, který je následován stručným popisem této postavy, vysvětlením a zdůvodněním mého překladu. Klíčová slova: Terry Pratchett, překlad, překladatelské postupy, fantasy, vlastnosti, rysy, Knittlová, Newmark.