Commemorating the Troubles in Northern Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constituency: Newry and Armagh

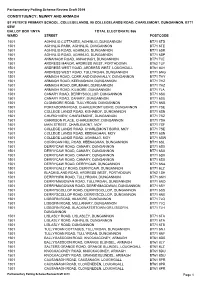

Parliamentary Polling Scheme Review Draft 2019 CONSTITUENCY: NEWRY AND ARMAGH ST PETER'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, COLLEGELANDS, 90 COLLEGELANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON, BT71 6SW BALLOT BOX 1/NYA TOTAL ELECTORATE 966 WARD STREET POSTCODE 1501 AGHINLIG COTTAGES, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TD 1501 AGHINLIG PARK, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TE 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SR 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SP 1501 ANNAHAGH ROAD, ANNAHAGH, DUNGANNON BT71 7JE 1501 ARDRESS MANOR, ARDRESS WEST, PORTADOWN BT62 1UF 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, ARDRESS WEST, LOUGHGALL BT61 8LH 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NG 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, CORR AND DUNAVALLY, DUNGANNON BT71 7HY 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, DRUMARN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KILMORE, DUNGANNON BT71 7JA 1501 CANARY ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CANARY ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CLONMORE ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NB 1501 PORTADOWN ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, DUNGANNON BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KISHABOY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SN 1501 CHURCHVIEW, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SZ 1501 GARRISON PLACE, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SA 1501 MAIN STREET, CHARLEMONT, MOY BT71 7SF 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, MOY BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KEENAGHAN, MOY BT71 6SN 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, AGHINLIG, MOY BT71 6SW 1501 CORRIGAN HILL ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6SL 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, -

“Éire Go Brách” the Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20Th Into the 21St Centuries

“Éire go Brách” The Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20th into the 21st Centuries Alexandra Watson Honors Thesis Dr. Giacomo Gambino Department of Political Science Spring 2020 Watson 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Literature Review: Irish Nationalism -- What is it ? 5 A Brief History 18 ‘The Irish Question’ and Early Roots of Irish Republicanism 20 Irish Republicanism and the War for Independence 25 The Anglo Irish Treaty of 1921, Pro-Treaty Republicanism vs. Anti-Treaty Republicanism, and Civil War 27 Early Statehood 32 ‘The Troubles’ and the Good Friday Agreement 36 Why is ‘the North’ Different? 36 ‘The Troubles’ 38 The Good Friday Agreement 40 Contemporary Irish Politics: Irish Nationalism Now? 45 Explaining the Current Political System 45 Competing nationalisms Since the Good Friday Agreement and the Possibility of Unification 46 2020 General Election 47 Conclusions 51 Appendix 54 Acknowledgements 57 Bibliography 58 Watson 3 Introduction In June of 2016, the people of the United Kingdom democratically elected to leave the European Union. The UK’s decision to divorce from the European Union has brought significant uncertainty for the country both in domestic and foreign policy and has spurred a national identity crisis across the United Kingdom. The Brexit negotiations themselves, and the consequences of them, put tremendous pressure on already strained international relationships between the UK and other European countries, most notably their geographic neighbour: the Republic of Ireland. The Anglo-Irish relationship is characterized by centuries of mutual antagonism and the development of Irish national consciousness, which ultimately resulted in the establishment of an autonomous Irish free state in 1922. -

The Outbreak and Development of the 'Troubles'

Heritage, History & Memory Project (Workshop 3) The outbreak and development of the ‘Troubles’ A presentation by Prof. John Barry followed by a general discussion compiled by Michael Hall ISLAND 115 PAMPHLETS 1 Published March 2019 by Island Publications 132 Serpentine Road, Newtownabbey BT36 7JQ © Michael Hall 2019 [email protected] http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/islandpublications The Fellowship of the Messines Association gratefully acknowledge the support they have received from the Heritage Lottery Fund for their Heritage, History & Memory Project and the associated publications Printed by Regency Press, Belfast 2 Introduction The Fellowship of the Messines Association was formed in May 2002 by a diverse group of individuals from Loyalist, Republican and Trade Union backgrounds, united in their realisation of the necessity to confront sectarianism in our society as a necessary means of realistic peace-building. The project also engages young people and new citizens on themes of citizenship and cultural and political identity. In 2018 the Association initiated its Heritage, History & Memory Project. For the inaugural launch of this project it was decided to focus on the period of the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement, and the early stages of the ‘Troubles’. To accomplish this, it was agreed to host a series of six workshops, looking at different aspects of that period, with each workshop developing on from the previous one. The format for each workshop would comprise a presentation by a respected commentator/historian, which would then be followed by a general discussion involving people from diverse political backgrounds, who would be encouraged to share not only their thoughts on the presentation, but their own experiences and memories of the period under discussion. -

Irish History Links

Irish History topics pulled together by Dan Callaghan NC AOH Historian in 2014 Athenry Castle; http://www.irelandseye.com/aarticles/travel/attractions/castles/Galway/athenry.shtm Brehon Laws of Ireland; http://www.libraryireland.com/Brehon-Laws/Contents.php February 1, in ancient Celtic times, it was the beginning of Spring and later became the feast day for St. Bridget; http://www.chalicecentre.net/imbolc.htm May 1, Begins the Celtic celebration of Beltane, May Day; http://wicca.com/celtic/akasha/beltane.htm. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ February 14, 269, St. Valentine, buried in Dublin; http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/irhismys/valentine.htm March 17, 461, St. Patrick dies, many different reports as to the actual date exist; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11554a.htm Dec. 7, 521, St. Columcille is born, http://prayerfoundation.org/favoritemonks/favorite_monks_columcille_columba.htm January 23, 540 A.D., St. Ciarán, started Clonmacnoise Monastery; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04065a.htm May 16, 578, Feast Day of St. Brendan; http://parish.saintbrendan.org/church/story.php June 9th, 597, St. Columcille, dies at Iona; http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Columcille.html Nov. 23, 615, Irish born St. Columbanus dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/04137a.htm July 8, 689, St. Killian is put to death; http://allsaintsbrookline.org/celtic_saints/killian.html October 13, 1012, Irish Monk and Bishop St. Colman dies; http://www.stcolman.com/ Nov. 14, 1180, first Irish born Bishop of Dublin, St. Laurence O'Toole, dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/09091b.htm June 7, 1584, Arch Bishop Dermot O'Hurley is hung by the British for being Catholic; http://www.exclassics.com/foxe/dermot.htm 1600 Sept. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

The RUC Handling of Certain Intelligence and Its Relationship with Government Communications Headquarters in Relation to the Omagh Bomb on 15 August 1998

Investigation Report The RUC handling of certain intelligence and its relationship with Government Communications Headquarters in relation to the Omagh Bomb on 15 August 1998 Public Statement by the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland arising from a referral by the Chief Constable, in accordance with Section 62 of the Police (Northern Ireland) Act 1998 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 On 4 May 2010, I received a Referral from the Chief Constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) concerning a number of specific matters relating to the manner in which the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) Special Branch handled both intelligence and its relationship with Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) in relation to the Omagh Bombing on 15 August 1998. The referral originated from issues identified by the House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee. 1.2 In 2013 the Chief Constable made a further Referral to my Office in connection with the findings of a report commissioned by the Omagh Support and Self Help Group (OSSHG) in support of a full Public Inquiry into the Omagh Bombing. The report identified and discussed a wide range of issues, including a reported tripartite intelligence led operation based in the Republic of Ireland involving American, British and Irish Agencies, central to which was a named agent. It suggested that intelligence from this operation was not shared prior to, or with those who subsequently investigated the Omagh Bombing. 1 1.3 On 12 September 2013 the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Theresa Villiers M.P. issued a statement explaining that there were not sufficient grounds to justify a further inquiry beyond those that had already taken place. -

Report of Sir Peter Gibson

REVIEW OF INTERCEPTED INTELLIGENCE IN RELATION TO THE OMAGH BOMBING OF 15 AUGUST 1998 [Extracts from full report] Sir Peter Gibson, the Intelligence Services Commissioner 16th January 2009 Terms of Reference by Gordon Brown, then British Prime Minister, 17 September 2008: “Review any intercepted intelligence material available to the security and intelligence agencies in relation to the Omagh bombing and how this intelligence was shared” These extracts from the full report were made available by Shaun Woodward, then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, on 20 January 2009 16th January 2009 REVIEW OF INTERCEPTED INTELLIGENCE IN RELATION TO THE OMAGH BOMBING OF 15 AUGUST 1998 CONTENTS Introduction 2 Context 3 Background to the bombing 5 The Investigations and Actions taken after the Bombing 6 Roles and relationships 9 Sources of information relating to my review 12 Conclusions 13 Acknowledgments 16 1 of 16 Introduction 1. Following the BBC Panorama programme broadcast on 15 September, the Prime Minister invited me, as the Intelligence Services Commissioner, to “review any intercepted intelligence material available to the security and intelligence agencies in relation to the Omagh bombing and how this intelligence was shared”. 2. In preparing my Report, which I presented to the Prime Minister on 18 December 2008, I drew on a range of very sensitive and highly classified material made available to me by those agencies involved in the production of intercept intelligence. Some of this material is subject to important legal constraints on its handling and disclosure. Such material, if released more widely, would reveal information on the capabilities of our security and intelligence agencies. -

A Short History of Irish Memory in the Long Twentieth Century

Thomas Bartlett (ed.), The Cambridge History of Ireland Irish Memory in the Long Twentieth Century (Cambridge, 2018), vol. IV: 1800 to Present would later be developed by his disciple Maurice Halbwachs, who coined the term collective memory ('la memoire collective'). By calling attention to the social frameworks in which memory is framed ('les cadres sociaux de la 23 · memoire'), Halbwachs presented a sound theoretical model for understand ing how individual members of a society collectively remember their past. 3 A Short History of Irish Memory in The impression that modernisation had uprooted people from tradition and the Long Twentieth Century that mass society suffered from atomised impersonality gave birth to a vogue GUY BEINER for commemoration, which was seen as a fundamental act of communal soli darity, in that it projected an illusion of continuity with the past.4 Ireland, outside of Belfast, did not undergo industrialisation on a scale comparable with England, and yet Irish society was not spared the upheaval On the cusp of the twentieth century; Ireland was obsessed with memoriali of modernity. The Great Famine had decimated vernacular Gaelic culture sation. This condition reflected a transnational zeitgeist that was indicative of and resulted in massive emigration. An Irish variant of fin de siecle angst over a crisis of memory throughout Europe. The outcome of rapid modernisa degeneration fed on apprehensions that British rule would ultimately result tion, manifested through changes ushered in by such far-reaching processes in the loss of 'native' identity. The perceived threat to national culture, artic as industrialisation, urbanisation, commercialisation and migration, raised ulated in Douglas Hyde's manifesto on 'The Necessity for De-Anglicising fears that the rituals and customs through which the past had been habitually Ireland' (1892), stimulated a vigorous response in the form of the Irish Revival remembered in the countryside were destined to be swept away. -

A Comparative Study of Extremism Within Nationalist Movements

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF EXTREMISM WITHIN NATIONALIST MOVEMENTS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM AND SPAIN by Ashton Croft Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors in the Department of History Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas 22 April 2019 Croft 1 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF EXTREMISM WITHIN NATIONALIST MOVEMENTS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM AND SPAIN Project Approved: Supervising Professor: William Meier, Ph.D. Department of History Jodi Campbell, Ph.D. Department of History Eric Cox, Ph.D. Department of Political Science Croft 2 ABSTRACT Nationalism in nations without statehood is common throughout history, although what nationalism leads to differs. In the cases of the United Kingdom and Spain, these effects ranged in various forms from extremism to cultural movements. In this paper, I will examine the effects of extremists within the nationalism movement and their overall effects on societies and the imagined communities within the respective states. I will also compare the actions of extremist factions, such as the Irish Republican Army (IRA), the Basque Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA), and the Scottish National Liberation Army (SNLA), and examine what strategies worked for the various nationalist movements at what points, as well as how the movements connected their motives and actions to historical memory. Many of the groups appealed to a wider “imagined community” based on constructing a shared history of nationhood. For example, violence was most effective when it directly targeted oppressors, but it did not work when civilians were harmed. Additionally, organizations that tied rhetoric and acts back to actual histories of oppression or of autonomy tended to garner more widespread support than others. -

The Troubles in Northern Ireland and Theories of Social Movements

11 PROTEST AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Bosi & De Fazio (eds) Bosi Fazio & De and Theories of of Theories and in Northern Ireland The Troubles Social Movements Social Edited by Lorenzo Bosi and Gianluca De Fazio The Troubles in Northern Ireland and Theories of Social Movements The Troubles in Northern Ireland and Theories of Social Movements Protest and Social Movements Recent years have seen an explosion of protest movements around the world, and academic theories are racing to catch up with them. This series aims to further our understanding of the origins, dealings, decisions, and outcomes of social movements by fostering dialogue among many traditions of thought, across European nations and across continents. All theoretical perspectives are welcome. Books in the series typically combine theory with empirical research, dealing with various types of mobilization, from neighborhood groups to revolutions. We especially welcome work that synthesizes or compares different approaches to social movements, such as cultural and structural traditions, micro- and macro-social, economic and ideal, or qualitative and quantitative. Books in the series will be published in English. One goal is to encourage non- native speakers to introduce their work to Anglophone audiences. Another is to maximize accessibility: all books will be available in open access within a year after printed publication. Series Editors Jan Willem Duyvendak is professor of Sociology at the University of Amsterdam. James M. Jasper teaches at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. The Troubles in Northern Ireland and Theories of Social Movements Edited by Lorenzo Bosi and Gianluca De Fazio Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Two rows of RUC Land Rovers keeping warring factions, the Nationalists (near the camera) and Loyalists, apart on Irish Street, Downpatrick. -

Dziadok Mikalai 1'St Year Student

EUROPEAN HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY Program «World Politics and economics» Dziadok Mikalai 1'st year student Essay Written assignment Course «International relations and governances» Course instructor Andrey Stiapanau Vilnius, 2016 The Troubles (Northern Ireland conflict 1969-1998) Plan Introduction 1. General outline of a conflict. 2. Approach, theory, level of analysis (providing framework). Providing the hypothesis 3. Major actors involved, definition of their priorities, preferences and interests. 4. Origins of the conflict (historical perspective), major actions timeline 5. Models of conflicts, explanations of its reasons 6. Proving the hypothesis 7. Conclusion Bibliography Introduction Northern Ireland conflict, called “the Troubles” was the most durable conflict in the Europe since WW2. Before War in Donbass (2014-present), which lead to 9,371 death up to June 3, 20161 it also can be called the bloodiest conflict, but unfortunately The Donbass War snatched from The Troubles “the victory palm” of this dreadful competition. The importance of this issue, however, is still essential and vital because of challenges Europe experience now. Both proxy war on Donbass and recent terrorist attacks had strained significantly the political atmosphere in Europe, showing that Europe is not safe anymore. In this conditions, it is necessary for us to try to assume, how far this insecurity and tensions might go and will the circumstances and the challenges of a international relations ignite the conflict in Northern Ireland again. It also makes sense for us to recognize that the Troubles was also a proxy war to a certain degree 23 Sources, used in this essay are mostly mass-media articles, human rights observers’ and international organizations reports, and surveys made by political scientists on this issue. -

Inventory of Closed Mine Waste Facilities in Northern Ireland. Phase 1 Data Collection and Categorisation

Inventory of closed mine waste facilities in Northern Ireland - Phase 2 Assessment Minerals and Waste Programme Commercial Report CR/14/031N BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MINERALS AND WASTE PROGRAMME COMMERCIAL REPORT CR/14/031 N Inventory of closed mine waste facilities in Northern Ireland - Phase 2 Assessment B Palumbo-Roe, K Linley, D Cameron, J Mankelow Contributor/editor T Johnston, MC Cowan The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database rights 2014. Ordnance Survey Licence No. 100021290. Keywords Mine waste Directive; Inventory; Northern Ireland. Bibliographical reference B PALUMBO-ROE, K LINLEY, D CAMERON, J MANKELOW. 2014. Inventory of closed mine waste facilities in Northern Ireland - Phase 2 Assessment. British Geological Survey Commercial Report, CR/14/031. 66pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. © NERC 2014. All rights reserved Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2014 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of our publications is available from BGS shops at British Geological Survey offices Nottingham, Edinburgh, London and Cardiff (Welsh publications only) see contact details below or shop online at www.geologyshop.com BGS Central Enquiries Desk Tel 0115 936 3143 Fax 0115 936 3276 The London Information Office also maintains a reference collection of BGS publications, including maps, for consultation.