Unconventional Responses to Unique Catastrophes Kenneth R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lapa Public Lectures and Workshops

LAPA PUBLIC LECTURES AND WORKSHOPS In addition to LAPA’s regular seminar series and conference events, LAPA also sponsors or cosponsors public lectures, informal workshops and other events that are not part of a regular series. Those events are listed here, from the most recent back to LAPA’s beginnings. Robert C. Post, David Boies Professor of Law at Yale Law School Third Annual Donald S. Bernstein ’75 Lecture May 3, 2007, 4:30 pm Robert C. Post joined the Yale faculty as the first David Boies Professor of Law. He focuses his teaching and writing on constitutional law, and is a specialist in the area of First Amendment theory and constitutional jurisprudence. Before coming to Yale Law, he had been teaching since 1983 at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law (Boalt Hall). Post is the author of Constitutional Domains: Democracy, Community, Management and co-author with K. Anthony Appiah, Judith Butler, Thomas C. Grey and Reva Siegel of Prejudicial Appearances: The Logic of American Antidiscrimination Law. He edited or co- edited Civil Society and Government, Human Rights in Political Transitions: Gettysburg to Bosnia, Race and Representation: Affirmative Action, Censorship and Silencing: Practices of Cultural Regulation and Law and Order of Culture. His scholarship has appeared academic journals in the humanities as well as in dozens of important law review articles, many in recent years with his colleague Reva Siegel. In 2003, he wrote the important Harvard Law Review “foreword” to its annual review of Supreme Court jurisprudence. Post was a law clerk to Chief Judge David L. -

Department of the Treasury FOIA Log 2010 1 Requestor Requesting

Department of the Treasury FOIA Log 2010 Requestor Requesting Organization Request Short Description Request Type Number (b) (6) 2010-01-001 request for records concerning IG Investigations closed since October 1, 2008 FOIA (b) (6) 2010-01-002 request for records concerning personal matters. FOIA Stephen Meardon Bowdoin College 2010-01-003 request for records concerning a report produced within the Division of Monetary FOIA Research in 1938 John Lehrer Baker Hostetler 2010-01-004 request for records pertaining to Revenue Ruling 2006-27, 2006-1 C.B. 915. FOIA Geoffry Walsh National Consumer Law 2010-01-005 request for records concerning Making Home Affordable Program documents FOIA Center Stephen Meardon Bowdoin College 2010-01-006 request for records concerning a 1938 report regarding "The Criteria for Determining FOIA Injury to Domestic Injury (Anti-Dumping Act of 1921) (b) (6) 2010-01-007 request for records pertaining to personal matters FOIA (b) (6) 2010-01-008 request for records concerning personal matters FOIA (b) (6) 2010-01-009 request for records concerning personal matters FOIA (b) (6) 2010-01-010 request for records concerning Secretary Geither's Presidential Commission and Oath FOIA of Office. (b) (6) 2010-01-011 request for records concerning personal matters FOIA (b) (6) 2010-01-012 request for records concerning custody permitting or granting Wachovia Bank or any FOIA of its top holders to be agents for general government (b) (6) 2010-01-013 request for records concerning personal matters FOIA (b) (6) 2010-01-014 request -

The September 11Th Victim Compensation Fund

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship Winter 2003 Grief, Procedure and Justice: The eptS ember 11th Victim Compensation Fund Elizabeth M. Schneider Brooklyn Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons, Legal Remedies Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation 53 DePaul L. Rev. 457 (2003-2004) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. GRIEF, PROCEDURE, AND JUSTICE: THE SEPTEMBER 11TH VICTIM COMPENSATION FUND Elizabeth M. Schneider* INTRODUCTION The September 11th Victim Compensation Fund of 2001 is unprece- dented in the American legal system. The Victim Compensation Fund emerged from congressional efforts to bail out the airlines from law- suits arising from the September 11th tragedy. The compromise was to give those who lost family members, or were injured, something in return for waiving the right to sue the airlines-to give them compen- sation for their loss. In this Article, I examine the Fund through the lens of the ex- traordinary grief and trauma-both collective and individual-that has shaped our post-September 11th psychic, social, and political land- scape. The grief and trauma that we have experienced as individuals and as a nation is unprecedented-a level of fear, anxiety, sadness, and a sense of horror as what was previously unimaginable has now become imaginable. Because the grief and trauma experienced as a result of September 11th has been so profound, so widely shared, and so public, it is especially important to consider these issues in assessing the Fund. -

The BP Oil Spill Settlements, Classwide Punitive Damages, and Societal Deterrence

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Via Sapientiae: The Institutional Repository at DePaul University DePaul Law Review Volume 64 Issue 2 Winter 2015: Twentieth Annual Clifford Symposium on Tort Law and Social Policy - In Article 19 Honor of Jack Weinstein The BP Oil Spill Settlements, Classwide Punitive Damages, and Societal Deterrence Catherine M. Sharkey Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Catherine M. Sharkey, The BP Oil Spill Settlements, Classwide Punitive Damages, and Societal Deterrence, 64 DePaul L. Rev. (2015) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol64/iss2/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BP OIL SPILL SETTLEMENTS, CLASSWIDE PUNITIVE DAMAGES, AND SOCIETAL DETERRENCE Catherine M. Sharkey* INTRODUCTION In late 2012, BP p.l.c. (BP) funded the Court Supervised Settlement Program as part of a class action settlement of the consolidated mul- tidistrict litigation arising from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. The BP settlement provided solely for compensatory damages to claimants. It left open the possibility that claimants eligi- ble for punitive damages could be certified as a class for litigation or settlement purposes against BP’s codefendants (but not BP) in the future. In 2014, Halliburton Company (Halliburton) (one of BP’s co- defendants) reached such a classwide punitive damages settlement. -

United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana

Case 2:10-md-02179-CJB-SS Document 912 Filed 12/21/10 Page 1 of 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA IN RE: OIL SPILL by the OIL RIG * MDL NO. 2179 “DEEPWATER HORIZON” IN THE * GULF OF MEXICO, on APRIL 20, 2010 * * THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: * JUDGE BARBIER * ALL CASES * MAG. JUDGE SHUSHAN * ******************************************* MOTION TO SUPERVISE EX PARTE COMMUNICATIONS BETWEEN BP DEFENDANTS AND PUTATIVE CLASS MEMBERS N OW INTO COURT come Plaintiffs, who respectfully pray for an order governing ex parte communication between the BP Defendants and putative class members, for the reasons that follow: I . Plaintiffs do not ask the Court to dictate, enjoin or otherwise interfere with the processing or payment of claims by BP thru the Gulf Coast Claims Facility (“GCCF”). II. Plaintiffs, rather, seek to ensure that the proposed Release and associated communications with putative classmembers are neither confusing nor misleading. Case 2:10-md-02179-CJB-SS Document 912 Filed 12/21/10 Page 2 of 8 III BP has been playing a “Shell Game” with the GCCF from the very beginning. When BP wants to rely on the GCCF’s presentment process, or take credit for what the GCCF is doing, then BP freely invokes and adopts the activities of the Claims Facility. When, on the other hand, BP wants to avoid responsibility for the GCCF, or to shield the GCCF from legal or professional responsibilities, then the Claims Facility becomes “independent” from BP. IV. The GCCF should either be a truly separate and independent trust or other juridical entity, with full access and transparency, and attendant fiduciary or other duties to a defined set of beneficiaries, based on a defined set of criteria; or, if, in the alternative, the GCCF is nothing more than an alter ego of the BP Defendants, Mr. -

Compensation for Economic Loss Following an Oil Spill Incident: Building a New Framework for Thailand

Compensation for Economic Loss Following an Oil Spill Incident: Building a New Framework for Thailand Tidarat Sinlapariromsuk A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Donsheng Zang, Chair William Rodgers Sanne Knudsen Usha Varanasi Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Law © Copyright 2017 Tidarat Sinlapapiromsuk University of Washington Abstract Compensation for Economic Loss Following an Oil Spill Incident: Building a New Framework for Thailand Tidarat Sinlapapiromsuk Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor of Law Dongsheng Zang School of Law The Rayong Oil Spill of 2013 presents a useful example of the catastrophic consequences of a large oil spill in Thailand, consequences that can provide meaningful lessons for industry and government. Many local residents and businesses throughout the coastal communities in Rayong suffered economic loss largely due to damages to natural resources; however, under the existing legal regime, there is no effective comprehensive legal framework that directly and adequately regulates the compensation regimes that handle claims of economic-loss following an oil-spill incident. Equally, as an alternative to litigation, there is no adequate guidance for the regimes handling rapid compensation payments for such type of claims. In the aftermath of the Rayong Spill, the responsible bodies developed the out-of-court compensation program on the fly, struggling to find a proper way to respond to this unprecedented disaster—yet this response was so haphazard that it left some claimants without clear rights to compensation, or, conceivably, it even left them with unfair levels of compensation. -

Prometheus Unbound: the Gulf Coast Claims Facility As a Means for Resolving Mass Tort Claims - a Fund Too Far, 71 La

Louisiana Law Review Volume 71 | Number 3 Spring 2011 Prometheus Unbound: The ulG f Coast Claims Facility as a Means for Resolving Mass Tort Claims - A Fund Too Far Linda S. Mullenix Repository Citation Linda S. Mullenix, Prometheus Unbound: The Gulf Coast Claims Facility as a Means for Resolving Mass Tort Claims - A Fund Too Far, 71 La. L. Rev. (2011) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol71/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Prometheus Unbound: The Gulf Coast Claims Facility as a Means for Resolving Mass Tort Claims-A Fund Too Far Linda S. Mullenix* I. INTRODUCTION In the well-known Greek myth, Prometheus stole fire from the Greek god Zeus and gave it to humanity. In return for this arrogance, Zeus had Prometheus chained to a rock in the Caucasus Mountains where Prometheus was punished by an eagle eating away at his liver, which regenerated every night. Because Prometheus was immortal, he was condemned to eternal torture by the voracious eagle's pecking. After 30 years of this punishment, however, Hercules appeared, killed the eagle, and liberated Prometheus from his unending torment. In return for freeing him, Prometheus rewarded Hercules with the secret to completing the 11th of his famous Herculean labors.' On April 20, 2010, an explosion on the Deepwater Horizon rig killed 11 workers and unleashed the worst oil spill in American history. -

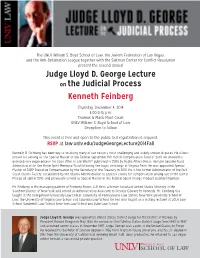

Judge Lloyd D. George Lecture on the Judicial Process Kenneth Feinberg

The UNLV William S. Boyd School of Law, the Jewish Federation of Las Vegas, and the Anti-Defamation League together with the Saltman Center for Conflict Resolution present the second annual Judge Lloyd D. George Lecture on the Judicial Process Kenneth Feinberg Thursday, December 4, 2014 4:00-5:15 p.m. Thomas & Mack Moot Court UNLV William S. Boyd School of Law Reception to follow This event is free and open to the public, but registration is required. RSVP at law.unlv.edu/JudgeGeorgeLecture2014Fall Kenneth R. Feinberg has been key to resolving many of our nation’s most challenging and widely known disputes. He is best known for serving as the Special Master of the Federal September 11th Victim Compensation Fund of 2001. He shared his extraordinary experience in his book What Is Life Worth?, published in 2005 by Public Affairs Press. He later became Fund Administrator for the Hokie Spirit Memorial Fund following the tragic shootings at Virginia Tech. He was appointed Special Master of TARP Executive Compensation by the Secretary of the Treasury in 2010. He is the former Administrator of the Gulf Coast Claims Facility, established by the Obama Administration to process claims for compensation arising out of the Gulf of Mexico oil spill in 2010, and previously served as Special Master in the Federal Agent Orange Product Liability litigation. Mr. Feinberg is the managing partner of Feinberg Rozen, LLP. He is a former Assistant United States Attorney in the Southern District of New York and served as Administrative Assistant to Senator Edward M. Kennedy. Mr. -

Liability and Compensation Issues Raised by the 2010 Gulf Oil Spill

Liability and Compensation Issues Raised by the 2010 Gulf Oil Spill Updated March 11, 2011 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R41679 Liability and Compensation Issues Raised by the 2010 Gulf Oil Spill Summary The 2010 Deepwater Horizon incident produced the largest oil spill that has occurred in U.S. waters, releasing more than 200 million gallons into the Gulf of Mexico. BP has estimated the combined oil spill costs—cleanup activities, natural resource and economic damages, potential Clean Water Act (CWA) penalties, and other obligations—will be approximately $41 billion. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill raised many issues for policymakers, including the ability of the existing oil spill liability and compensation framework to respond to a catastrophic spill. This framework determines (1) who is responsible for paying for oil spill cleanup costs and the economic and natural resource damages from an oil spill; (2) how these costs and damages are defined (i.e., what is covered?); and (3) the degree to which, and conditions in which, the costs and damages are limited and/or shared by other parties, including general taxpayers. The existing framework includes a combination of elements that distribute the costs of an oil spill between the responsible party (or parties) and the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund (OSLTF), which is largely financed through a per-barrel tax on domestic and imported oil. Responsible parties are liable up to their liability caps (if applicable); the trust fund covers costs above liability limits up to a per-incident cap of $1 billion. Policymakers may want to consider the magnitude of the Deepwater Horizon incident and the liability and compensation issues raised under a scenario in which BP had refused to finance response activities or establish a claims process to comply with the relevant OPA provisions. -

Unconventional Responses to Unique Catastrophes: Tailoring the Law to Meet the Challenges Kenneth R

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 46 | Issue 3 2014 Unconventional Responses to Unique Catastrophes: Tailoring the Law to Meet the Challenges Kenneth R. Feinberg Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Kenneth R. Feinberg, Unconventional Responses to Unique Catastrophes: Tailoring the Law to Meet the Challenges, 46 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 525 (2014) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol46/iss3/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. CASE WESTERN RESERVE JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW·VOL. 46·2014 Unconventional Responses to Unique Catastrophes: Tailoring the Law to Meet the Challenges Kenneth R. Feinberg* I want to thank the Dean at the outset. He says I know a lot about opera and baseball. I guess it was obstruction when he slid into third base. I mean, it doesn’t require any mens rea, so it is a strict liability offense. So if the runner is impeded, that’s the end of it I guess. Everybody seemed to think it was the right call, but I don’t know who will win the World Series. But I want to thank the Dean for those kind words. I want to thank Roe Green for her philanthropy, for so much that she does to validate the memory of her father, and I hope that in some small way my work and what I do exemplifies what Ben stood for as a judge and as a man. -

August 16, 2010

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF LEGISLATION AND PUBLIC POLICY D’Agostino Hall • 110 West Third Street • New York, NY 10012-1074 [email protected] • www.nyu.edu/pubs/jlpp 2010–2011 ANNUAL REPORT Introduction Established in 1997, The Journal of Legislation and Public Policy (“JLPP”) is a nonpartisan periodical specializing in the analysis of state and federal legislation and policy. In particular, JLPP seeks to provide a forum for legislators, judges, legal academics, and lawyers to discuss contemporary legislative issues. The journal publishes three issues per year, and each issue consists of a mix of articles and student notes. In addition to publishing these issues, JLPP hosts symposia and other events of public significance. During the 2010–2011 academic year, hundreds of students, alumni, and members of the public attended JLPP’s celebration of the legislative legacy of Senator Edward M. Kennedy. The event featured remarks delivered by Justice Stephen Breyer, Caroline Kennedy, Kenneth Feinberg, Thomas Susman, and Nick Littlefield. During the 2011–2012 academic year, JLPP will be hosting two events. On October 24, 2011, JLPP is excited to host New York State Court of Appeals Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman. The event, entitled Equal Justice at Risk: Confronting the Crisis in Civil Legal Services, will also feature Judge Robert Katzmann of the Second Circuit, Alan Levine, and Helaine Barnett. JLPP is also co-hosting a symposium on Internet Governance and Regulation on February 24, 2011. We are happy to update you about JLPP’s successes this academic year and are excited to highlight our goals for the upcoming academic year. -

Legal Legacy of the Deepwater Horizon Catastrophe:Settle Or Sue?

Roger Williams University Law Review Volume 17 | Issue 1 Article 8 Winter 2012 Blowout: Legal Legacy of the Deepwater Horizon Catastrophe:Settle or ue?S The seU and Structure of Alternative Compensation Programs in the Mass Claims Context Deborah E. Greenspan Dickstein Shapiro LLP Matthew A. euburN ger Dickstein Shapiro LLP Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/rwu_LR Recommended Citation Greenspan, Deborah E. and Neuburger, Matthew A. (2012) "Blowout: Legal Legacy of the Deepwater Horizon Catastrophe:Settle or Sue? The sU e and Structure of Alternative Compensation Programs in the Mass Claims Context," Roger Williams University Law Review: Vol. 17: Iss. 1, Article 8. Available at: http://docs.rwu.edu/rwu_LR/vol17/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Roger Williams University Law Review by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Settle or Sue? The Use and Structure of Alternative Compensation Programs in the Mass Claims Context Deborah E. Greenspan* and Matthew A. Neuburger* * Deborah Greenspan is the co-leader of Dickstein Shapiro's Complex Dispute Resolution Group. Her practice focuses on class action, mass tort and bankruptcy law and procedure with a particular expertise in mass torts and products liability, analysis of damages and future liability exposure, negotiation, alternative dispute resolution, claims evaluation and dispute analysis, settlement distribution design and implementation, claims management and risk analysis, and general litigation. She has represented clients in the most significant complex litigation matters in the United States.