Preliminary Project Report of the FWF Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Violence Against Kosovar Albanians, Nato's

VIOLENCE AGAINST KOSOVAR ALBANIANS, NATO’S INTERVENTION 1998-1999 MSF SPEAKS OUT MSF Speaks Out In the same collection, “MSF Speaking Out”: - “Salvadoran refugee camps in Honduras 1988” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2003 - April 2004 - December 2013] - “Genocide of Rwandan Tutsis 1994” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2003 - April 2004 - April 2014] - “Rwandan refugee camps Zaire and Tanzania 1994-1995” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2003 - April 2004 - April 2014] - “The violence of the new Rwandan regime 1994-1995” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2003 - April 2004 - April 2014] - “Hunting and killings of Rwandan Refugee in Zaire-Congo 1996-1997” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [August 2004 - April 2014] - ‘’Famine and forced relocations in Ethiopia 1984-1986” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [January 2005 - November 2013] - “MSF and North Korea 1995-1998” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [January 2008 - 2014] - “War Crimes and Politics of Terror in Chechnya 1994-2004” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [June 2010 -2014] -”Somalia 1991-1993: Civil war, famine alert and UN ‘military-humanitarian’ intervention” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2013] Editorial Committee: Laurence Binet, Françoise Bouchet-Saulnier, Marine Buissonnière, Katharine Derderian, Rebecca Golden, Michiel Hofman, Theo Kreuzen, Jacqui Tong - Director of Studies (project coordination-research-interviews-editing): Laurence Binet - Assistant: Berengere Cescau - Transcription of interviews: Laurence Binet, Christelle Cabioch, Bérengère Cescau, Jonathan Hull, Mary Sexton - Typing: Cristelle Cabioch - Translation into English: Aaron Bull, Leah Brummer, Nina Friedman, Imogen Forst, Malcom Leader, Caroline Lopez-Serraf, Roger Leverdier, Jan Todd, Karen Tucker - Proof reading: Rebecca Golden, Jacqui Tong - Design/lay out: - Video edit- ing: Sara Mac Leod - Video research: Céline Zigo - Website designer and webmaster: Sean Brokenshire. -

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order Online

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order online Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Glossary 1. Executive Summary The 1999 Offensive The Chain of Command The War Crimes Tribunal Abuses by the KLA Role of the International Community 2. Background Introduction Brief History of the Kosovo Conflict Kosovo in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Kosovo in the 1990s The 1998 Armed Conflict Conclusion 3. Forces of the Conflict Forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Yugoslav Army Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs Paramilitaries Chain of Command and Superior Responsibility Stucture and Strategy of the KLA Appendix: Post-War Promotions of Serbian Police and Yugoslav Army Members 4. march–june 1999: An Overview The Geography of Abuses The Killings Death Toll,the Missing and Body Removal Targeted Killings Rape and Sexual Assault Forced Expulsions Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions Destruction of Civilian Property and Mosques Contamination of Water Wells Robbery and Extortion Detentions and Compulsory Labor 1 Human Shields Landmines 5. Drenica Region Izbica Rezala Poklek Staro Cikatovo The April 30 Offensive Vrbovac Stutica Baks The Cirez Mosque The Shavarina Mine Detention and Interrogation in Glogovac Detention and Compusory Labor Glogovac Town Killing of Civilians Detention and Abuse Forced Expulsion 6. Djakovica Municipality Djakovica City Phase One—March 24 to April 2 Phase Two—March 7 to March 13 The Withdrawal Meja Motives: Five Policeman Killed Perpetrators Korenica 7. Istok Municipality Dubrava Prison The Prison The NATO Bombing The Massacre The Exhumations Perpetrators 8. Lipljan Municipality Slovinje Perpetrators 9. Orahovac Municipality Pusto Selo 10. Pec Municipality Pec City The “Cleansing” Looting and Burning A Final Killing Rape Cuska Background The Killings The Attacks in Pavljan and Zahac The Perpetrators Ljubenic 11. -

Cultural Heritage, Reconstruction and National Identity in Kosovo

1 DOI: 10.14324/111.444.amps.2013v3i1.001 Title: Identity and Conflict: Cultural Heritage, Reconstruction and National Identity in Kosovo Author: Anne-Françoise Morel Architecture_media_politics_society. vol. 3, no.1. May 2013 Affiliation: Universiteit Gent Abstract: The year 1989 marked the six hundredth anniversary of the defeat of the Christian Prince of Serbia, Lazard I, at the hands of the Ottoman Empire in the “Valley of the Blackbirds,” Kosovo. On June 28, 1989, the very day of the battle's anniversary, thousands of Serbs gathered on the presumed historic battle field bearing nationalistic symbols and honoring the Serbian martyrs buried in Orthodox churches across the territory. They were there to hear a speech delivered by Slobodan Milosevic in which the then- president of the Socialist Republic of Serbia revived Lazard’s mythic battle and martyrdom. It was a symbolic act aimed at establishing a version of history that saw Kosovo as part of the Serbian nation. It marked the commencement of a violent process of subjugation that culminated in genocide. Fully integrated into the complex web of tragic violence that was to ensue was the targeting and destruction of the region’s architectural and cultural heritage. As with the peoples of the region, this heritage crossed geopolitical “boundaries.” Through the fluctuations of history, Kosovo's heritage had already become subject to divergent temporal, geographical, physical and even symbolical forces. During the war it was to become a focal point of clashes between these forces and, as Anthony D. Smith argues with regard to cultural heritage more generally, it would be seen as “a legacy belonging to the past of ‘the other,’” which, in times of conflict, opponents try “to damage or even deny.” Today, the scars of this conflict, its damage and its denial are still evident. -

Behind Stone Walls

BEHIND STONE WALLS CHANGING HOUSEHOLD ORGANIZATION AMONG THE ALBANIANS OF KOSOVA by Berit Backer Edited by Robert Elsie and Antonia Young, with an introduction and photographs by Ann Christine Eek Dukagjini Balkan Books, Peja 2003 1 This book is dedicated to Hajria, Miradia, Mirusha and Rabia – girls who shocked the village by going to school. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Berita - the Norwegian Friend of the Albanians, by Ann Christine Eek BEHIND STONE WALLS Acknowledgement 1. INTRODUCTION Family and household Family – types, stages, forms Demographic processes in Isniq Fieldwork Data collection 2. ISNIQ: A VILLAGE AND ITS FAMILIES Once upon a time Going to Isniq Kosova First impressions Education Sources of income and professions Traditional adaptation The household: distribution in space Household organization Household structure Positions in the household The household as an economic unit 3. CONJECTURING ABOUT AN ETHNOGRAPHIC PAST Ashtu është ligji – such are the rules The so-called Albanian tribal society The fis The bajrak Economic conditions Land, labour and surplus in Isniq The political economy of the patriarchal family or the patriarchal mode of reproduction 3 4. RELATIONS OF BLOOD, MILK AND PARTY MEMBERSHIP The traditional social structure: blood The branch of milk – the female negative of male positive structure Crossing family boundaries – male and female interaction Dajet - mother’s brother in Kosova The formal political organization Pleqësia again Division of power between partia and pleqësia The patriarchal triangle 5. A LOAF ONCE BROKEN CANNOT BE PUT TOGETHER The process of the split Reactions to division in the family Love and marriage The phenomenon of Sworn Virgins and the future of sex roles Glossary of Albanian terms used in this book Bibliography Photos by Ann Christine Eek 4 PREFACE ‘Behind Stone Walls’ is a sociological, or more specifically, a social anthropological study of traditional Albanian society. -

Property Rights in Kosovo: a Haunting Legacy of a Society

O C C A S I O N A L P A P E R S E RIE S PROPERTY RIGHTS IN KOSOVO: A HAUNTING LEGACY OF A SOCIETY IN TRANSITION Written by Edward Tawil for the International Center for Transitional Justice February 2009 ©2009 International Center for Transitional Justice This document may be cited as Edward Tawil, Property Rights in Kosovo: A Haunting Legacy of a Society in Transition (2009), International Center for Transitional Justice ABOUT THE ICTJ The International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) assists countries pursuing accountability for past mass atrocity or human rights abuse. The Center works in societies emerging from repressive rule or armed conflict, as well as in established democracies where historical injustices or systemic abuse remain unresolved. In order to promote justice, peace, and reconciliation, government officials and nongovernmental advocates are likely to consider a variety of transitional justice approaches including both judicial and non-judicial responses to human rights crimes. The ICTJ assists in the development of integrated, comprehensive, and localized approaches to transitional justice comprising five key elements: prosecuting perpetrators, documenting and acknowledging violations through non-judicial means such as truth commissions, reforming abusive institutions, providing reparations to victims, and facilitating reconciliation processes. The Center is committed to building local capacity and generally strengthening the emerging field of transitional justice, and works closely with organizations and experts around the world to do so. By working in the field through local languages, the ICTJ provides comparative information, legal and policy analysis, documentation, and strategic research to justice and truth-seeking institutions, nongovernmental organizations, governments, and others. -

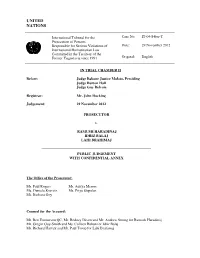

Haradinaj Judgement

UNITED NATIONS International Tribunal for the Case No. IT-04-84 bis -T Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of Date: 29 November 2012 International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991 Original: English IN TRIAL CHAMBER II Before: Judge Bakone Justice Moloto, Presiding Judge Burton Hall Judge Guy Delvoie Registrar: Mr. John Hocking Judgement: 29 November 2012 PROSECUTOR v. RAMUSH HARADINAJ IDRIZ BALAJ LAHI BRAHIMAJ PUBLIC JUDGEMENT WITH CONFIDENTIAL ANNEX The Office of the Prosecutor: Mr. Paul Rogers Mr. Aditya Menon Ms. Daniela Kravetz Ms. Priya Gopalan Ms. Barbara Goy Counsel for the Accused: Mr. Ben Emmerson QC, Mr. Rodney Dixon and Mr. Andrew Strong for Ramush Haradinaj Mr. Gregor Guy-Smith and Ms. Colleen Rohan for Idriz Balaj Mr. Richard Harvey and Mr. Paul Troop for Lahi Brahimaj CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1 II. CONSIDERATIONS REGARDING THE EVALUATION OF EVIDENCE........................4 III. STRUCTURE AND ORGANISATION OF THE KLA IN THE DUKAGJIN ZONE ........6 A. EMERGENCE AND GENERAL STRUCTURE OF THE KLA..................................................................6 1. KLA General Staff...................................................................................................................6 2. Number of KLA forces in 1998...............................................................................................7 3. The KLA zones -

The Kosovar Albanian Family Revisited"

Preliminary Project Report of the FWF Project "The Kosovar Albanian Family Revisited" Project Leader: Prof. Karl Kaser FWF Project Number: P22659-G18 Family in a Fragile State and Economy in Kosovo: The Case of Opoja by Elife Krasniqi The drawing on the cover named ‘My Family’ was done by Erblina Qafleshi (5) in the ‘Sezai Surroi’ school, village of Bellobrad, Opoja. 31.10. 2012 Eli Krasniqi, Centre for Southeast European History and Anthropology, University of Graz 1 Introduction In a postwar country such as Kosovo, societal transformations are inevitable. In regard to family, these changes have impacted not only structure and size but also everyday family life. The project "Family in Kosovo- Revisited" carried out at the Center for Southeast European History and Anthropology (SEEHA) at the University of Graz and funded by the Austrian Science Fund, has been researching changes over time in the Kosovar family in relation to social security and social cohesion. The research has focused on two regions in Kosovo, Isniq and Opoja, in order to track the changes after the war in 1998 and 1999. Isniq and Opoja are prime locations for this study, because of the two PhD projects that were conducted there before the war: Reineck's study about Opoja (1991), and Backer's (1979) on Isniq. Both researches were conducted in very peculiar political periods in Kosovo that surely impacted both social and cultural life. The project team consists of Dr. Carolin Leutloff- Grandits, who focuses on migration in both regions - Isniq and Opoja, Mag. Tahir Latifi (Isniq) and me, researching the Opoja region, as well as Prof. -

Administrator

REPORT ON THE INTEGRATED APPEAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL RED CROSS AND RED CRESCENT MOVEMENT IN RESPONSE TO THE 1999 BALKANS CRISIS ICRC/International Federation Steering Group Geneva, November 2000 Table of contents List of abbreviations Preamble ................................................................................................................................I Part A - From the Kosovo conflict to the Balkans crisis .....................................................1 I. Two conflicts ...........................................................................................................1 II. Humanitarian consequences ..................................................................................1 a) The exodus ....................................................................................................................... 1 b) The air campaign .............................................................................................................. 2 c) Returnees ......................................................................................................................... 2 d) Displaced Serbs and Roma ............................................................................................... 3 II. The humanitarian response ....................................................................................3 a) Characteristics .................................................................................................................. 3 b) Militarization of assistance ................................................................................................ -

Business Climate in Kosovo a Cross-Regional Perspective

2.2.3 Sensitivity analysis AnAN EU FUNDED funded PROJECTproject MANAGED BY THE IMPLEMENTEDImplemented BY by : managed by the European * * EUROPEAN UNION OFFICE RIINVESTRIINVEST INSTITUTE * * UnionIN KOSOVO Office in Kosovo A CROSS-REGIONAL PERSPECTIVE 2 | BUSINESS CLIMATE IN KOSOVO A CROSS-REGIONAL PERSPECTIVE 2014 BUSINESS CLIMATE IN KOSOVO | 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 07 LIST OF ACRONYMS 63 5. FOCUS GROUP RESULTS 09 INTRODUCTION 63 5.1. Barriers to SME growth 63 a) Labour-force barriers 64 b) Infrastructural barriers 65 c) Financial barriers 11 1. KOSOVO AT A GLANCE 65 d) Legal barriers 12 1.1. Private sector development in Kosovo 66 e) Fiscal barriers 66 5.2. Relation between businesses and institutions 66 a) Involvement of businesses in policy-making 15 2. PROFILES OF THE FIVE ECONOMIC REGIONS OF KOSOVO 67 b) The level of financial support by the central government and local governments 23 3. METHODOLOGY 67 c) RDAs and their role 68 5.3. Evaluation of regional development strategies 70 5.4. Sectors with growth potential 25 4. SURVEY FINDINGS 25 4.1. SME Performance 31 4.2. The general list of barriers to doing business 75 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 34 4.3. The detailed analysis of barriers to SME development 34 a) Financial barriers 80 REFERENCES 37 b) Informality-related barriers 40 c) Fiscal barriers 42 d) Legal barriers 45 e) Institutional barriers 47 f) Labour force barriers 48 g) Infrastructural barriers 51 h) Other Barriers 54 4.4. Summary of the future of businesses and their barriers 56 4.5. Perspectives of businesses on local and national institutions 4 | BUSINESS CLIMATE IN KOSOVO BUSINESS CLIMATE IN KOSOVO | 5 Financed by: The European Union Office in Kosovo and Association of Regional Development Agencies 2.2.3 Sensitivity analysis Disclaimer: This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. -

Slapp Suits Seeking to Silence Enviornmental Activists Must

www.amnesty.org AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC STATEMENT 28 June 2021 EUR 73/43 50/2021 KOSOVO: SLAPP SUITS SEEKING TO SILENCE ENVIRONMENTAL ACTIVISTS MUST END Kelkos Energy should withdraw the defamation lawsuits filed against environmental activists in Kosovo* as they appear to be designed to obstruct their work, intimidate, and silence them, Amnesty International said today. As unfounded and disproportionate claims for damages have become a clear barrier for the work of human rights defenders and civil society organizations, authorities should take appropriate measures to ensure a safe and enabling environment in which they can operate without fear of reprisals. Kelkos Energy, a large Austrian-based hydropower management company with operations in Kosovo,1 has used defamation lawsuits and threats of such lawsuits to target activists who publicly speak about the environmental impact of hydropower plants operating in the country’s natural protected areas and the lack of necessary scrutiny by Kosovo’s authorities in the process of issuing operating licenses for such plants. On 1 June 2020, Kelkos Energy filed a defamation lawsuit against Shpresa Loshaj, an environmental activist and the founder of the non-governmental organization Pishtarët (Torches). In the lawsuit, Kelkos Energy asked for EUR 100,000 in damages for Ms Loshaj’s public campaigning against the company’s operations in the Deçan/Dečani (Deçan) region, where Kelkos Energy manages four hydropower plants. Kelkos Energy has also demanded that Ms Loshaj publicly retract and apologize for her statements and refrain from stating “untrue facts” about the company in the future.2 In a similar lawsuit in January 2020, Kelkos Energy demanded EUR 10,000 in reputational damages from Adriatik Gacaferi, an environmental activist from Deçan resulting from a Facebook post criticizing the company’s hydropower plant operations in the Deçan region.3 Kelkos Energy demanded that Mr Gacaferi remove the contested post and publish a retraction. -

An Autoethnographic Study of a Kosovar Student

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses, 2020-current The Graduate School 5-7-2020 Finding my feet: An autoethnographic study of a Kosovar student Erjona Gashi Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029 Part of the International and Intercultural Communication Commons Recommended Citation Gashi, Erjona, "Finding my feet: An autoethnographic study of a Kosovar student" (2020). Masters Theses, 2020-current. 49. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029/49 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses, 2020-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Finding My Feet: An Autoethnographic Study of a Kosovar Student A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of the Arts School of Communication Studies May 2020 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Dr. Michael Broderick Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Carlos Aleman Dr. Iccha Basnyat Acknowledgments “Faleminderit.” I say to the many people who have spent countless hours in guiding, supporting, and challenging me throughout the writing of this project. “Thank you.” I say to the individuals who have contributed in meaningful and creative ways, by sharing experiences, listening to my ramblings, cooking me food and bringing me coffee, and by being extra sets of eyes and ears while reading and editing my work. This thesis project would have never happened if it were not primarily for the generosity of President Alger who initiated the Madison Vision Assistantship for the Advancement of Kosovo. -

Serbia (Includes Kosovo)

Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Serbia Page 1 of 23 Serbia (includes Kosovo) Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2007 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 11, 2008 The Republic of Serbia is a parliamentary democracy with approximately 7.5 million inhabitants.* Prime Minister V time limits. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces. The government generally respected the human rights of its citizens and continued efforts to address human rights concerns; speech and religion; societal intolerance and discrimination against ethnic and religious minorities, particularly Roma; large nu During the year the government assisted in the arrests of Zdravko Tolimir and Vlastimir Djordjevic, two of the remaining six in RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life There were no reports that the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. On May 23, the Belgrade special court for organized crime concluded the trial of 12 suspects, including former secret police s years in prison. The other defendants received sentences ranging from the minimum of eight years to 35 years in prison. Spe In June the Supreme Court upheld its 2006 confirmation of the conviction of Ulemek and others for the 2000 killing of former S Investigation continued into the deaths of Dragan Jakovljevic and Drazen Milovanovic, two guards from Belgrade's Topcider m filed in 2005 against the military prosecutor, Vuk Tufegzdic. The judge issued a warning to Tufegzdic, now a judge, and fined The government continued its investigation into the disappearance and subsequent killing of Yili, Mehmet, and Agron Bytyqi i Stojanovic.