Forfeiting Our Commons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Life and Contributions of Jagalur Mohammed Imam, Politician of India

International Journal in Management and Social Science Volume 08 Issue 02, February 2020 ISSN: 2321-1784 Impact Factor: 6.178 Journal Homepage: http://ijmr.net.in, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal A STUDY OF THE LIFE AND CONTRIBUTIONS OF JAGALUR MOHAMMED IMAM, POLITICIAN OF INDIA Dr. Doddamani Lokaraja. A.K. Assistant Professor Department of Sociology Government first grade college, Jagalur, Davanagere dist. Karnataka State, India. PIN No: 577 528 Abstract: Jagalur Mohammed Imam is very close to the predecessors of independent India. He has served in state politics for over 30 years and in central politics for 5 years. People called him Immanna, Immanna by love. His grandparents, Fakir Saheb and his father, Badesabe, became members of the Democratic Party, doing public work in local bodies and becoming a populace. As the first municipal president of Jagalur, the Imam put much effort into providing civic amenities. He was the chairman of the Chitradurga District Board from 1936 to 1940. He was appointed as a private minister during the Mysore Maharaja's era and was the recipient of the ‘Mushir-ul-Mul’ Award by the Maharaja for his efficient handling of railway, irrigation, philanthropy, education, cooperation, police and industry. In 1957 he contested from the Chitradurga constituency and was a member of the Lok Sabha. Chitradurga, a backward district, has been admired by people for its many public works such as roads, bridges and drinking water wells. Introduction : After the pre-independent era of India and the post-independent politicians were simple-minded politician, chauffeur of the Karnataka Unification Movement, the leader of the four-party opposition in the Mysore government, Jagalur Mohammed Imam, a pioneer of efficiency and honesty and social concern. -

LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 731 to BE ANSWERED on 23Rd JULY, 2018

LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 731 TO BE ANSWERED ON 23rd JULY, 2018 Survey for Petrol Pumps 731. SHRI BHAGWANTH KHUBA: पेट्रोलियम एवं प्राकृ तिक गैस मंत्री Will the Minister of PETROLEUM AND NATURAL GAS be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government have conducted proposes to conduct any survey to open new petrol pumps and new LPG distributorships/dealerships in Hyderabad and Karnataka and if so, the details thereof; and (b) the name of the places where new petrol pump and LPG dealership have been opened / proposed to be opened open after the said survey? ANSWER पेट्रोलियम एवं प्राकृ तिक गैस मंत्री (श्री धमेन्द्र प्रधान) MINISTER OF PETROLEUM AND NATURAL GAS (SHRI DHARMENDRA PRADHAN) (a) Expansion of Retail Outlets (ROs) and LPG distributorships network by Oil Marketing Companies (OMCs) in the country is a continuous process. ROs and LPG distributorships are set up by OMCs at identified locations based on field survey and feasibility studies. Locations found to be having sufficient potential as well as economically viable are rostered in the Marketing Plans for setting up ROs and LPG distributorships. (b) OMCs have commissioned 342 ROs (IOCL:143, BPCL:89 & HPCL:110) in Karnataka and Hyderabad during the last three years and current year. State/District/Location-wise number of ROs where Letter of Intents have been issued by OMCs in the State of Karnataka and Hyderabad as on 01.07.2018 is given in Annexure-I. Details of locations advertised by OMCs for LPG distributorship in the state of Karnataka is given in Annexure-II. -

Prl. District and Session Judge, Belagavi. Sri. Chandrashekhar Mrutyunjaya Joshi PRL

Prl. District and Session Judge, Belagavi. Sri. Chandrashekhar Mrutyunjaya Joshi PRL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE BELAGAVI Cause List Date: 22-09-2020 Sr. No. Case Number Timing/Next Date Party Name Advocate 11.00 AM-02.00 PM 1 Crl.Misc. 1405/2020 Gurusidda Shanker Chandaragi Patil A.R. (HEARING) Age 39yrs R/o yattinkeri Tq Kittur Dt Belagavi Vs The State of Karnataka R/by P.P. Belagavi 2 Crl.Misc. 596/2020 Kasimsab Sultansab Nadaf Age. V.S.Karajagi (NOTICE) 33 years R/o Sankeshwar ,Tal. Hukkeri, Belagavi. Vs Salma W/o Kasimsab Nadaf Age. 31 years R/o M.G Colony, Bailhongal, Belagavi. 3 SC 102/2017 State of Karnataka R/by PP SPL.PP (EVIDENCE) Belagavi. Vs Najim Nilawar @ Mahammad Najim Nilawar age 51yrs R/o Bandar Road Batkal Dt Uttar Kannada. 4 SC 141/2019 The State of Karnataka R/by PP, PP (F.D.T.) Belagavi. Vs I Y Chobri Kareppa Basappa Nayik Age. 33 years R/o Budraynoor,Tal.Belagavi. 5 SC 380/2019 The State of Karnataka PP (HBC) Vs Bharmappa alias Bharma Chandru Kurabagatti age 20 yrs R/o Sahyadri colony Jaitun Mal Udyambhag BGV 6 SC 47/2020 The State of Karnataka R/by PP, PP (ISSUE NBW TO Belagavi. ACCUSED) Vs Raj Shravan Londe Age. 21 years R/o Gyangawadi, Shivabasav Nagar, Belagavi. 7 Crl.Misc. 1442/2020 Vaibhav Rajendra Patil Age Shaikh M.M. (OBJECTION) 29yrs R/o Sai Anand Bungalow Sant Gnyaneshwar Nagar, Majagaon Belagavi Vs The State of Karnataka R/by Public Prosecutor Belagavi. 8 Crl.Misc. -

Independent Engineer Services Forfour Laning from Km 308.550 To

National Highways Authority of India Request for Proposal for IE NATIONAL HIGHWAYS AUTHORITY OF INDIA (MINISTRY OF ROAD TRANSPORT & HIGHWAYS, GOVT.OF INDIA) Plot No. G-5 & 6, Sector – 10, Dwarka New Delhi – 110 075 Independent Engineer services forFour laning from km 308.550 to km 358.500, Byrapura to Challakere section of NH-150 A, on Hybrid Annuity Mode under Bharatmala Pariyojna in the State of Karnataka. REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) <May , 2018> CONTENTS Particulars SECTION 1: INFORMATION TO CONSULTANTS ........................................... 3-8 SECTION 2: LETTER OF INVITATION TO CONSULTANTS ............................... 9-39 SECTION 3: FORMATS FOR SUBMISSION OF FIRMS CREDENTIALS .................. 40-44 SECTION 4: FORMAT FOR SUBMISSION OF TECHNICAL PROPOSAL ................. 45-61 SECTION 5: FORMAT FOR SUBMISSION OF FINANCIAL PROPOSAL. ................ 62-70 SECTION 6: TERMS OF REFERENCE FOR INDEPENDENT ENGINEER ............... 71-218 SECTION 7: DRAFT FORM OF CONTRACT ........................................... 219-268 2 National Highways Authority of India Request for Proposal for IE REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) SECTION 1: INFORMATION TO CONSULTANTS Sub.: Independent Engineer services for Four laning from km 308.550 to km 358.500, Byrapura to Challakere section of NH-150 A, on Hybrid Annuity Mode under Bharatmala Pariyojna in the State of Karnataka GENERAL:- 1. The National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) invites proposals for engaging an Independent Engineer (IE) on the basis of International Competitive Bidding for the following contract package in the State of Karnataka under NHDP Phase - programme. TABLE 1: DETAILS OF PROJECT S No Consultancy NH No. State Project Project Assignment Package Stretch Length period (Km)/Total (months) Project Cost (Cr.) 1 NH Karnataka Km 49.95Km 48months NHAI/KNT-NH- 150(A)/Pkg-2/150(A) 308.550to /841.70 Crs IE/2018 Km 358.500 / 2. -

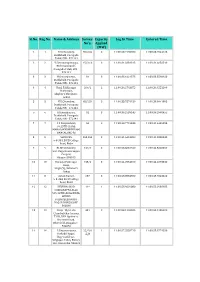

Sl.No. Reg.No. Name & Address Survey No's. Capacity Applied (MW

Sl.No. Reg.No. Name & Address Survey Capacity Log In Time Entered Time No's. Applied (MW) 1 1 H.V.Chowdary, 65/2,84 3 11:00:23.7195700 11:00:23.7544125 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 2 2 Y.Satyanarayanappa, 15/2,16 3 11:00:31.3381315 11:00:31.6656510 Bheemunikunte, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 3 3 H.Ramanjaneya, 81 3 11:00:33.1021575 11:00:33.5590920 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 4 4 Hanji Fakkirappa 209/2 2 11:00:36.2763875 11:00:36.4551190 Mariyappa, Shigli(V), Shirahatti, Gadag 5 5 H.V.Chowdary, 65/2,84 3 11:00:38.7876150 11:00:39.0641995 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 6 6 H.Ramanjaneya, 81 3 11:00:39.2539145 11:00:39.2998455 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 7 7 C S Nanjundaiah, 56 2 11:00:40.7716345 11:00:41.4406295 #6,15TH CROSS, MAHALAKHSMIPURAM, BANGALORE-86 8 8 SRINIVAS, 263,264 3 11:00:41.6413280 11:00:41.8300445 9-8-384, B.V.B College Road, Bidar 9 9 BLDE University, 139/1 3 11:00:23.8031920 11:00:42.5020350 Smt. Bagaramma Sajjan Campus, Bijapur-586103 10 10 Basappa Fakirappa 155/2 3 11:00:44.2554010 11:00:44.2873530 Hanji, Shigli (V), Shirahatti Gadag 11 11 Ashok Kumar, 287 3 11:00:48.8584860 11:00:48.9543420 9-8-384, B.V.B College Road, Bidar 12 12 DEVUBAI W/O 11* 1 11:00:53.9029080 11:00:55.2938185 SHARANAPPA ALLE, 549 12TH CROSS IDEAL HOMES RAJARAJESHWARI NAGAR BANGALORE 560098 13 13 Girija W/o Late 481 2 11:00:58.1295585 11:00:58.1285600 ChandraSekar kamma, T105, DNA Opulence, Borewell Road, Whitefield, Bangalore - 560066 14 14 P.Satyanarayana, 22/*/A 1 11:00:57.2558710 11:00:58.8774350 Seshadri Nagar, ¤ltĔ Bagewadi Post, Siriguppa Taluq, Bellary Dist, Karnataka-583121 Sl.No. -

Unit 6 Animal Husbandry

UNIT 6 ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Structure Introduction Objectives DairyingIDairy Farming Animal By-Products Cattle Breeding Development of Dairy Industry In India Poultry Development Sheep Development Piggery Development Fishery Development Cattle Insurance Summary Answers to SAQs - 6.1 INTRODUCTION The origin of livestock wealth is as old as the evolution of human society. !n fact, this living wealth and the human society are interdependent. There is no denyir g the fact the livestock wealth apart from being the main source of National health is a tc 3k of economic prosperity specially in a country like India, where about 82 percent of the p: ~pulationis ruralite and the economy is agro-based. The present status of animal husbas ndry and dairy enterprise has emerged out of age old development activities. In this unit, not only the dairying activity, but all the allied activities like pot~ltry development, piggery development, sheep development, fisheries developm :nt, dairy industry and cattle insurance have been taken. Objectives After studying this unit, you should be able to explain present system of dairy farming in India, list various dairy products, discuss development of dairy industry in different five year plans., describe the present status of poultry, sheep, piggery, catile,and fisher J farming, discuss the role of insurance in dairying, and discuss problems and prospects of dairy industry. 6.2 DAIRYINGIDAIRY FARMING This section deals with the history of cattle and buffaloes, their classification aczo ding to the purpose of keeping cattle, milk production and its utilisation, animal by-produc ts, cattle breeding and dairy industry. The Pre-historic Draft Concept Indian cattle cannot be studied without delving deep into over 5000 years of history snd understanding the cattle needs of the country of those days. -

Cause List Date: 11-12-2020

Prl. District and Session Judge, Belagavi. Sri. Chandrashekhar Mrutyunjaya Joshi PRL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE BELAGAVI Cause List Date: 11-12-2020 Sr. No. Case Number Timing/Next Date Party Name Advocate 11.00 AM-02.00 PM 1 Misc 225/2019 ShriNarasimhaDevVaishakhaUtsavTrust J. H. (HEARING) R/oMugatkhanHubli,Regi.UnderBPTActSl.No.A-2924R/byV.N.Koujalagi GOVANKOP, Vs Nil 2 COMM.O.S 18/2020 B.K.Gangadhar S/o B.K.Kempegowda age 59 yrs R/o Double road Kudsomanavar (HEARING) Kuvempu Nagar Mysore S.R. Vs The Managing Director KNNL 4th floor Coffee Board Building Dr. SRI. RAMESH Ambedkar Veedhi Bangalore N. MISALE, 3 R.A. 140/2020 Arjun Hanamant Janagouda, Age 65yrs, R/o. Naduvin Galli, Alarwad, B B OSI (HEARING) Tq.Dist. Belagavi Vs Sunanda Mahaveer Kyasannavar, Age 63 yrs, R/o. Mahaveer Galli, Halaga(Bastawad), Tq.Dist.Belagavi 4 COMM.O.S 5/2020 Chandrakant Krishna Gavas age 62 yrs R/o Sy.No. 18/2B Sainik nagar D.B.Swamy (SUMMONS) Camp Belagavi Vs Aatharvu Infra and Agro ltd. Dahisar Mumbai R/by S.S.Nikhade age 68 yrs R/o Anand nagar Dahisar 5 COMM.O.S 17/2020 B.K.Gangadhar S/o B.K.Kempegowda age 59 yrs R/o Double road Kudsomanavar (EVIDENCE) Kuvempu Nagar Mysore S.R. Vs The Managing Director KNNL 4th floor Coffee board Building Dr. SRI. RAMESH Ambedkar Veedhi Bangalore N. MISALE, 6 A.S. 11/2019 Megha Sapariya Piyash Age.35 yrsR/o.Flat No. 303 Hari OM M.M.Jamadar (ARGUMENTS) Apartments Near Hari Mandir Main Road.BGV. -

SAS Ann Report 2015-16 Geo Compressed Compressed.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 - 2016 CONTENTS S.No Titles2016 Page No. 1. Introduction 1 2. I. INTEGRATED RURAL DEVELOPMENT 1 3. Brief Description of the Context of the Project 1 4. Overall objective and specific objective of the project: 2 5. Activity 1: Women Empowerment through Self Help Group Movement and their Federation. 2 6. Women Empowerment through SHGs & Their Federations 3 7. A. Formation of new SHGs: 3 8. B. Training in Book Keeping and Financial Management: 3 9. C. Training in Personality Development for the new SHG members 3 10. D. Capacity Building Exercise: 3 11. E. Federations 4 12. F. Animation and Guidance of SHGs 5 13. G. Implementation of MGNREGA 6 14. H. Organic Farming 6 15. I. Role of Supervisors in Women Empowerment: 7 16. J. Shg Women Contested Gram Panchayat Election 7 17. WINGS TO WOMEN‟S ASPIRATIONS 8 18. Activity 2: Functional Vocational Training 9 19. CASE STUDIES: Case Studies of SHG Movement 11 20. Case Studies on Functional Vocational Training 20 21. Activity 3: II. ORGANIZATION BUILDING OF NOMADIC SHEPHERDS COMMUNITY IN NORTH 26 KARNATAKA (1 Aug 2014 to 31 Jul 2015) 22. Description of implemented measures and activities (Nos 1to 10). 27 23. Income Generation Activities 44 24. Strengthening and consolidation of OB process: 47 25. Case studies/stories of change 48 26. Activity 4: III. BIOGAS PLANT CUM TOILET UNIT 52 27. Project Background 52 28. Main objectives: 53 29. Measures (activities) and instruments used to achieve the objectives 53 30. Process and impact oriented project monitoring 55 31. Further development activities which have their origin in this 55 32. -

Gram Panchayat Human Development

Gram Panchayat Human Development Index Ranking in the State - Districtwise Rank Rank Rank Standard Rank in in Health in Education in District Taluk Gram Panchayat of Living HDI the the Index the Index the Index State State State State Bagalkot Badami Kotikal 0.1537 2186 0.7905 5744 0.7164 1148 0.4432 2829 Bagalkot Badami Jalihal 0.1381 2807 1.0000 1 0.6287 4042 0.4428 2844 Bagalkot Badami Cholachagud 0.1216 3539 1.0000 1 0.6636 2995 0.4322 3211 Bagalkot Badami Nandikeshwar 0.1186 3666 0.9255 4748 0.7163 1149 0.4284 3319 Bagalkot Badami Hangaragi 0.1036 4270 1.0000 1 0.7058 1500 0.4182 3659 Bagalkot Badami Mangalore 0.1057 4181 1.0000 1 0.6851 2265 0.4169 3700 Bagalkot Badami Hebbali 0.1031 4284 1.0000 1 0.6985 1757 0.4160 3727 Bagalkot Badami Sulikeri 0.1049 4208 1.0000 1 0.6835 2319 0.4155 3740 Bagalkot Badami Belur 0.1335 3011 0.8722 5365 0.5940 4742 0.4105 3875 Bagalkot Badami Kittali 0.0967 4541 1.0000 1 0.6652 2938 0.4007 4141 Bagalkot Badami Kataraki 0.1054 4194 1.0000 1 0.6054 4549 0.3996 4163 Bagalkot Badami Khanapur S.K. 0.1120 3946 0.9255 4748 0.6112 4436 0.3986 4187 Bagalkot Badami Kaknur 0.1156 3787 0.8359 5608 0.6550 3309 0.3985 4191 Bagalkot Badami Neelgund 0.0936 4682 1.0000 1 0.6740 2644 0.3981 4196 Bagalkot Badami Parvati 0.1151 3813 1.0000 1 0.5368 5375 0.3953 4269 Bagalkot Badami Narasapura 0.0902 4801 1.0000 1 0.6836 2313 0.3950 4276 Bagalkot Badami Fakirbhudihal 0.0922 4725 1.0000 1 0.6673 2874 0.3948 4281 Bagalkot Badami Kainakatti 0.1024 4312 0.9758 2796 0.6097 4464 0.3935 4315 Bagalkot Badami Haldur 0.0911 4762 -

The Science of A2 Beta Casein

Indian Journal of Open Science Publications Nutrition Volume 7, Issue 1 - 2020 © Sridharan P, et al. 2020 www.opensciencepublications.com The Science of A2 Beta Casein - A Critical Review of Global Data and Outcomes of Indian Study Review Article Pranesh Sridharan1* and Chidananda BL2 1Mathruka Cattle Farm & Research Center, India 2Department of Animal Sciences, University of Agricultural Sciences, GKVK, Bangalore, India *Corresponding author: Pranesh Sridharan, Mathruka Cattle Farm & Research Center, Bengaluru, India; E-mail: dr.pranesh@ gmail.com Article Information: Submission: 07/01/2020; Accepted: 15/02/2020; Published: 18/02/2020 Copyright: © 2020 Sridharan P, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Milk provides wholesome nutrition, rich in proteins, vitamins and calcium. Recent research has shown milk to be a risk factor for diseases as well. The new insights on A1 and A2 Beta-Casein proteins in milk has triggered significant interest globally in A2 milk, which is considered safe. This is a first comprehensive Indian study on A2 and A1 milk, encompassing review of published literature, genetic study of cattle in India and impact of A1 and A2 milk on health of individuals. Review of over 60 published in-vivo, in-vitro and epidemiological studies indicate that A1 Beta-casein triggers the opioid peptide cascade, leading to endogenous production of the opioid peptide BCM-7, that aggravates the risk factors of Type 1 Diabetes, IDDM, CHD, Autism, neurological disorders and hormonal imbalances.The risks associated with A1 protein have not been associated with A2 beta-casein. -

Unusual Aerosol Characteristics at Challakere in Karnataka

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Publications of the IAS Fellows RESEARCH ARTICLES Unusual aerosol characteristics at Challakere in Karnataka S. K. Satheesh1,2,*, K. Krishna Moorthy3, S. Suresh Babu3 and J. Srinivasan1,2 1Centre for Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences and 2Divecha Centre for Climate Change, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560 012, India 3Space Physics Laboratory, Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre, Thiruvananthapuram 695 022, India their controlling processes and estimation of their direct During a series of measurements, simultaneous meas- urements were made of spectral aerosol optical depths and indirect radiative forcing. (AOD), black carbon (BC) mass concentration, total In India, systematic studies of the physico-chemical and size segregated composite aerosol mass concentra- properties of aerosols, their temporal heterogeneities, tions at the second campus of Indian Institute of Sci- spectral characteristics, size distribution and modulation ence (IISc), Challakere, Karnataka. Surprisingly, of their properties by regional mesoscale and synoptic most of the aerosol mass is found in the submicron meteorological processes have been carried out exten- size range, which is unusual for a dry region. Unex- sively since the 1980s at different distinct geographical pectedly large enhancement in BC aerosol concentra- regions as part of the different national programmes such tion was observed during the morning hours (6–8 a.m.), as the Indian Middle Atmosphere Programme (I-MAP), both during -

Heritage of Mysore Division

HERITAGE OF MYSORE DIVISION - Mysore, Mandya, Hassan, Chickmagalur, Kodagu, Dakshina Kannada, Udupi and Chamarajanagar Districts. Prepared by: Dr. J.V.Gayathri, Deputy Director, Arcaheology, Museums and Heritage Department, Palace Complex, Mysore 570 001. Phone:0821-2424671. The rule of Kadambas, the Chalukyas, Gangas, Rashtrakutas, Hoysalas, Vijayanagar rulers, the Bahamanis of Gulbarga and Bidar, Adilshahis of Bijapur, Mysore Wodeyars, the Keladi rulers, Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan and the rule of British Commissioners have left behind Forts, Magnificient Palaces, Temples, Mosques, Churches and beautiful works of art and architecture in Karnataka. The fauna and flora, the National parks, the animal and bird sanctuaries provide a sight of wild animals like elephants, tigers, bisons, deers, black bucks, peacocks and many species in their natural habitat. A rich variety of flora like: aromatic sandalwood, pipal and banyan trees are abundantly available in the State. The river Cauvery, Tunga, Krishna, Kapila – enrich the soil of the land and contribute to the State’s agricultural prosperity. The water falls created by the rivers are a feast to the eyes of the outlookers. Historical bakground: Karnataka is a land with rich historical past. It has many pre-historic sites and most of them are in the river valleys. The pre-historic culture of Karnataka is quite distinct from the pre- historic culture of North India, which may be compared with that existed in Africa. 1 Parts of Karnataka were subject to the rule of the Nandas, Mauryas and the Shatavahanas; Chandragupta Maurya (either Chandragupta I or Sannati Chandragupta Asoka’s grandson) is believed to have visited Sravanabelagola and spent his last years in this place.