Walter Map's Reception in Nineteenth Century Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Welsh Folk-Lore Is Almost Inexhaustible, and in These Pages the Writer Treats of Only One Branch of Popular Superstitions

: CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Library Cornell UnlverBlty GR150 .095 welsh folMore: a co^^^^ 3 1924 029 911 520 olin Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tlie Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029911520 : Welsh Folk=Lore T A COI/LEGTION OF THE FOLK-TALES AND LEGENDS OF NOKTH WALES Efffl BEING THB PRIZE ESSAY OP THE NATIONAL EISTEDDFOD, 1887, BT THE Rev. ELIA.S QWEN, M.A., F.S.A. REVISED AND ENLARGED BY THE AUTHOR. OSWESTRY AND WREXHAM ; PRINTED AND PITBLISHKD BY WOODALL, MIKSHALL, AND 00. PREFACE. To this Essay on the " Folk-lore of North Wales," was awarded the first prize at the Welsh National Eisteddfod, held in London, in 1887. The prize consisted of a silver medal, and £20. The adjudicators were Canon Silvan Evans, Professor Rhys, and Mr Egerton PhiHimore, editor of the Gymmrodor. By an arrangement with the Eisteddfod Committee, the work became the property of the pubHshers, Messrs. Woodall, Minshall, & Co., who, at the request of the author, entrusted it to him for revision, and the present Volume is the result of his labours. Before undertaking the publishing of the work, it was necessary to obtain a sufficient number of subscribers to secure the publishers from loss. Upwards of two hundred ladies and gentlemen gave their names to the author, and the work of pubhcation was commenced. -

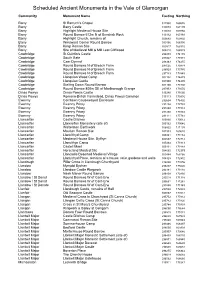

Scheduled Ancient Monuments in the Vale of Glamorgan

Scheduled Ancient Monuments in the Vale of Glamorgan Community Monument Name Easting Northing Barry St Barruch's Chapel 311930 166676 Barry Barry Castle 310078 167195 Barry Highlight Medieval House Site 310040 169750 Barry Round Barrow 612m N of Bendrick Rock 313132 167393 Barry Highlight Church, remains of 309682 169892 Barry Westward Corner Round Barrow 309166 166900 Barry Knap Roman Site 309917 166510 Barry Site of Medieval Mill & Mill Leat Cliffwood 308810 166919 Cowbridge St Quintin's Castle 298899 174170 Cowbridge South Gate 299327 174574 Cowbridge Caer Dynnaf 298363 174255 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 297025 173874 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 296929 173780 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 297133 173849 Cowbridge Llanquian Wood Camp 302152 174479 Cowbridge Llanquian Castle 301900 174405 Cowbridge Stalling Down Round Barrow 301165 174900 Cowbridge Round Barrow 800m SE of Marlborough Grange 297953 173070 Dinas Powys Dinas Powys Castle 315280 171630 Dinas Powys Romano-British Farmstead, Dinas Powys Common 315113 170936 Ewenny Corntown Causewayed Enclosure 292604 176402 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291294 177788 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291260 177814 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291200 177832 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291111 177761 Llancarfan Castle Ditches 305890 170012 Llancarfan Llancarfan Monastery (site of) 305162 170046 Llancarfan Walterston Earthwork 306822 171193 Llancarfan Moulton Roman Site 307383 169610 Llancarfan Llantrithyd Camp 303861 173184 Llancarfan Medieval House Site, Dyffryn 304537 172712 Llancarfan Llanvithyn -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

Architectural History

our historic church also holds a well-kept secret, Architectural History with its little-known but strong connections to two major literary scholars The origin of St Michael’s church is unknown, but we think it is early medieval due to it’s position beside the River Alwen and the curvature of the churchyard. The Norwich Taxation of 1254 OWAIN MYFYR makes reference to the church as ’Ecc’a de lanwihangel’, so we 1741—1814 know that the church is at least 13th century. A native of this village, Owen Jones was known by the bardic name Owain Myfyr. He The church has undergone a number of restorations since it was moved to London as a young man, and was first built, mainly due to a major flood that hit the village in 1781. apprenticed to a furrier. By the 1780s he The flood level rose to a height of more than 8ft inside the church, owned his own business and had amassed a sweeping away the east window and wall as the powerful waters large fortune. receded. A stone plaque to the left of the pulpit In the late 18th century, he co-founded the ‘Gwyneddigion marks the line of the flood. Society’, a London-Welsh society dedicated to encouraging the literary life of Wales, which provided the blueprint of the In 1853 the bellcote, east window and west end of the church were competitive Eisteddfod familiar to us today. rebuilt. It is thought that the south porch may also have been added at this time. In 1789 the work of Dafydd ap Gwilym was published, with Owain Myfyr as one of the editors. -

Activaleactivale Youth Directory - Llawlyfr Gwasanaethau Ieuenctid

activaleactivale youth directory - llawlyfr gwasanaethau ieuenctid Contents - Cynnwys Introduction & Acknowledgements 2 Cyflwyniad a Chydnabyddiaeth 3 Updating Information & Contact Details 4 Diweddaru Gwybodaeth Bersonol a Manylion Cysylltu 5 Registration Form 6 Ffurflen Gofrestru 6 It’s about You! 10 Mae hyn I gyd amdanoch chi! 13 Safe Practice 16 Cadw'n Ddiogel 17 Disclaimer 18 Ymwadiad 19 Our Use of Categories 20 Categorïau yn y llyfr 21 Alphabetical Index Category Index: arts index education index employment & training index environment index family & relationships index health index housing index information & advice index law & rights index leisure index money index sport index world & travel index 1 Introduction and Acknowledgements Activale is a directory of services for young people between the ages of 11 - 25 years. The Directory has been produced by the Children & Young Person's Information Service (CYPIS) through a joint project by the Young People's Partnership (YPP) and the 14-19 Network, funded by the Welsh Assembly Government. It has been produced with the help of other organisations including: Penarth Youth Project CLIC Online Young People's Partnership (YPP) 14-19 Network Vale Learning Network Sports Development Unit (Vale of Glamorgan Council) Libraries Service (Vale of Glamorgan Council) Vale Volunteer Bureau Barry College Learning & Development Directorate (Vale of Glamorgan Council) The aim is to provide a comprehensive source of information on all services and organisations that are accessible to young people, aged 11-25 years, and living in the Vale of Glamorgan. It is appropriate for use by young people themselves, carers of young people and professionals working with young people. -

Plu Hydref 2011 Fersiwn

PAPUR BRO LLANGADFAN, LLANERFYL, FOEL, LLANFAIR CAEREINION, ADFA, CEFNCOCH, LLWYDIARTH, LLANGYNYW, CWMGOLAU, DOLANOG, RHIWHIRIAETH, PONTROBERT, MEIFOD, TREFALDWYN A’R TRALLWM. 426 Hydref 2017 60c BRENIN Y BOWLIO LLYWYDDION LLAWEN Ar brynhawn Sul gwlyb yn ddiweddar chwaraewyd twrnamaint bowlio yn Llanfair Caereinion. Er gwaetha’r tywydd roedd y cystadleuwyr yn benderfynol o orffen y gystadleuaeth gan fod y ‘Rose Bowl’ yn wobr mor hynod o dlws i’w hennill. Yn y gêm derfynol roedd Gwyndaf James yn chwarae yn erbyn y g@r profiadol Llun Michael Williams Richard Edwards. Gwyndaf oedd y pencampwr hapus a fo gafodd ei ddwylo ar y ‘Rose Bowl’. Rwan mae Enillwyr y stondin fasnach orau ar faes y Sioe eleni oedd stondin ar y cyd Philip angen dod o hyd i le parchus i arddangos y wobr Edwards, For Farmers a H.V. Bowen. Gwelir Huw, Guto a Rhidian Glyn o For Farm- arbennig hon! ers; Mark Bowen a Philip yn derbyn eu gwobr gan Enid ac Arwel Jones. DWY NAIN FALCH Mae dwy nain falch iawn yn Nyffryn Banw yn dilyn yr Eisteddfod Genedlaethol yn Sir Fôn ym mis Awst. Uchod gwelir Dilys, Nyth y Dryw, Llangadfan gyda’i h@yr Steffan Prys Roberts, Llanuwchllyn a enillodd wobr y Rhuban Glas. Mae Steff yn gweithio i’r Urdd yng Nglanllyn ac yn aelod o Gwmni Theatr Maldwyn, tri chôr a sawl parti canu! Nain arall sy’n byrlymu â balchder yw Marion Owen, Rhiwfelen, Foel sy’n ymfalchïo yn llwyddiant ei hwyres Marged Elin Owen a enillodd Ysgoloriaeth yr Artist Ifanc. Mae Marged bellach wedi cael swydd gyda chwmni castio gwydr y tu allan i Blackpool. -

In England, Scotland, and Wales: Texts, Purpose, Context, 1138-1530

Victoria Shirley The Galfridian Tradition(s) in England, Scotland, and Wales: Texts, Purpose, Context, 1138-1530 A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature Cardiff University 2017 i Abstract This thesis examines the responses to and rewritings of the Historia regum Britanniae in England, Scotland, and Wales between 1138 and 1530, and argues that the continued production of the text was directly related to the erasure of its author, Geoffrey of Monmouth. In contrast to earlier studies, which focus on single national or linguistic traditions, this thesis analyses different translations and adaptations of the Historia in a comparative methodology that demonstrates the connections, contrasts and continuities between the various national traditions. Chapter One assesses Geoffrey’s reputation and the critical reception of the Historia between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, arguing that the text came to be regarded as an authoritative account of British history at the same time as its author’s credibility was challenged. Chapter Two analyses how Geoffrey’s genealogical model of British history came to be rewritten as it was resituated within different narratives of English, Scottish, and Welsh history. Chapter Three demonstrates how the Historia’s description of the island Britain was adapted by later writers to construct geographical landscapes that emphasised the disunity of the island and subverted Geoffrey’s vision of insular unity. Chapter Four identifies how the letters between Britain and Rome in the Historia use argumentative rhetoric, myths of descent, and the discourse of freedom to establish the importance of political, national, or geographical independence. Chapter Five analyses how the relationships between the Arthur and his immediate kin group were used to challenge Geoffrey’s narrative of British history and emphasise problems of legitimacy, inheritance, and succession. -

Trewallter Fawr, Walterston, Near Llancarfan, Vale of Glamorgan, CF62 3AS

Trewallter Fawr, Walterston, Near Llancarfan, Vale of Glamorgan, CF62 3AS Trewallter Fawr, Walterston Near Llancarfan, Vale of Glamorgan, CF62 3AS £795,000 Freehold 5 Bedrooms : 1 Bathrooms : 3 Reception Rooms An exceptional, Grade II* listed home to the very heart of the Vale offering extensive family accommodation and an immense wealth of character. Two large living rooms, both with open fires. Kitchen-breakfast room, scullery and garden room. Five bedrooms including a generous master bedroom. Includes a two-storey barn, outbuildings and large gardens, in all about 1.4 acres. Directions From our Cowbridge Office follow the A48 in an easterly direction towards Cardiff. Travel through Bonvilston, turning right at Sycamore Cross onto the A4226 ("Five Mile Lane") in the direction of Barry. Follow the road for close to 2 miles and turn right at the sign for Walterston. (This may involve some 'doubling back' whilst roadworks are being taken place). Follow this lane directly into the hamlet of Walterston, to find Trewallter Fawr to your left, set back behind a deep grass verge. A gated entrance leads into the yard to the side of the property, from which there is access to the property, to its gardens and to the barn. • Cowbridge 8.7 miles • Cardiff City Centre 10.1 miles • M4 (J33) 8.8 miles Your local office: Cowbridge T 01446 773500 E [email protected] Summary of Accommodation ABOUT THE PROPERTY * Located to the heart of the Vale yet within easy reach of Cardiff and Cowbridge * An exceptional, Grade II* listed property retaining -

The Uncanny and Unhomely in the Poetry of RS T

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY '[A] shifting/identity never your own' : the uncanny and unhomely in the poetry of R.S. Thomas Dafydd, Fflur Award date: 2004 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 "[A] shifting / identity never your own": the uncanny and the unhomely in the writing of R.S. Thomas by Fflur Dafydd In fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The University of Wales English Department University of Wales, Bangor 2004 l'W DIDEFNYDDIO YN Y LLYFRGELL YN UNIG TO BE CONSULTED IN THE LIBRARY ONLY Abstract "[A] shifting / identity never your own:" The uncanny and the unhomely in the writing of R.S. Thomas. The main aim of this thesis is to consider R.S. Thomas's struggle with identity during the early years of his career, primarily from birth up until his move to the parish of Aberdaron in 1967. -

Sustainable Settlements Apprai

Vale of Glamorgan Local Development Plan 2011 - 2026 Contents Page 1. Introduction 2 2. Context 3 3. Methodology 5 4. Initial Sustainability Rankings 12 5. Analysis 13 6. Conclusions 16 7. Use and Interpretation 20 Appendices Appendix 1 – Assessed Settlements Estimated Population 23 Appendix 2 – Vale of Glamorgan Revised Sustainable Settlements 25 Appraisal: Location and Boundaries of Appraised Settlements Appendix 3 – Vale of Glamorgan Revised Sustainable Settlements 26 Appraisal: Settlement Groupings Appendix 4 – Detailed Scoring of Settlements 27 Sustainable Settlements Apprai sal Review Background Paper 1 Vale of Glamorgan Local Development Plan 2011 - 2026 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Planning Policy Wales [PPW] (Fourth edition, 2011) requires Local Development Plans [LDPs] sustainable settlement strategies to be informed by an assessment of settlements to ensure they accord with the sustainable location principles contained within national planning policy (see PPW Section 4.6 Sustainable settlement strategy: locating new development). 1.2 As part of the evidence base for the Vale of Glamorgan LDP, the Council has undertaken an audit of services and facilities within the Vale of Glamorgan’s settlements in order to identify those which are potentially suitable to accommodate additional development in terms of their location, role and function. This assessment therefore forms part of the evidence base for the Vale of Glamorgan LDP Settlement Hierarchy by identifying broad groupings of settlements with similar roles and functions based upon the following research objectives: Objective 1: To assess the need for residents to commute beyond their settlement to access key employment, retail and community facilities (including education and health). Objective 2: To measure the general level of accessibility of settlements by sustainable transport. -

Geoffrey of Monmouth and Medieval Welsh Historical Writing

Chapter 9 The Most Excellent Princes: Geoffrey of Monmouth and Medieval Welsh Historical Writing Owain Wyn Jones A late 14th-century manuscript of Brut y Brenhinedd (“History of the Kings”), the Welsh translation of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s De gestis Britonum, closes with a colophon by the scribe, Hywel Fychan, Hywel Fychan ap Hywel Goch of Buellt wrote this entire manuscript lest word or letter be forgotten, on the request and command of his master, none other than Hopcyn son of Tomos son of Einion … And in their opinion, the least praiseworthy of those princes who ruled above are Gwrtheyrn and Medrawd [Vortigern and Mordred]. Since because of their treachery and deceit and counsel the most excellent princes were ruined, men whose descendants have lamented after them from that day until this. Those who suffer pain and subjection and exile in their native land.1 These words indicate the central role Geoffrey’s narrative had by this point as- sumed not only in vernacular historical writing, but also in the way the Welsh conceived of their past and explained their present. Hywel was writing around the time of the outbreak of Owain Glyn Dŵr’s revolt, and the ethnic and co- lonial grievances which led to that war are here articulated with reference to the coming of the Saxons and the fall of Arthur.2 During the revolt itself, Glyn Dŵr’s supporters justified his cause with reference to the Galfridian past, for 1 Philadelphia, Library Company of Philadelphia, 8680.O, at fol. 68v: “Y llyuyr h6nn a yscri- uenn6ys Howel Vychan uab Howel Goch o Uuellt yn ll6yr onys g6naeth agkof a da6 geir neu lythyren, o arch a gorchymun y vaester, nyt amgen Hopkyn uab Thomas uab Eina6n … Ac o’e barn 6ynt, anuolyannussaf o’r ty6yssogyon uchot y llywyassant, G6rtheyrn a Medra6t. -

A Creative Welsh Translator of Historia Regum Britanniae

Brynley Roberts YSTORIAEU BRENHINEDD YNYS BRYDEIN What I want to do in this short paper is simply to show how one Welsh translator undertook the task of translating, adapting and supplementing Geoffrey‟s Historia but I believe that analysing the text that he produced will contribute to our understanding of the broader issue of how the Latin text itself could be combined with other historical material. The paper is, however, not definitive but rather, „work in progress‟. This translation is one of a number of Welsh versions of the Historia. The 70 or so Welsh texts can be classified into 6 or 7 main groups, ignoring for the moment fragments or incomplete versions. Referring to the groups by the oldest ms in each (or the best known in one case), these are: 1. NLW Llanstephan ms 1, 13c.: selections edited (Roberts 1971); complete text edited and awaiting publication. 2. NLW Peniarth ms 44, 13c.: edited but not yet published (Roberts 1969). 3. NLW Dingestow ms 13c.: edited by Henry Lewis (Lewis 1942). These are pretty close translations of the Latin vulgate text, especially Llanstephan 1 (apart from the opening section that appears to follow the variant version), while Peniarth 44 abbreviates as it goes and unfortunately the ms lacks a number of folios towards the end. These two tend to translate sentence by sentence but Dingestow is less bound to the text (Roberts 1977). All three make a few additions – personal names have traditional epithets and patronymics, there are some additional comments or references to inconsistencies, new adjectives may be added.