The Mineral Industry of Australia in 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engineering & Mining Journal

Know-How | Performance | Reliability With MineView® and SmartFlow® Becker Mining Systems offers two comprehensive and scalable data management solutions for your Digital Mine. MineView® is a powerful state-of-the-art 3D SCADA system, that analyses incoming data from various mine equipment and visualises it in a 3D mine model. SmartFlow® takes Tagging & Tracking to a new level: collected asset data is centrally processed and smart software analytics allow for process optimization and improved safety. MINEVIEW BECKER MINING SYSTEMS AG We have been at the forefront of technology in Energy Distribution, Automation, Communication, Transportation and Roof Support since 1964. Together with our customers we create and deliver highest quality solutions and services to make operations run more profi tably, reliably and safely. For more information go to www.becker-mining.com/digitalmine Becker Mining is a trademark of Becker Mining Systems AG. © 2018 Becker Mining Systems AG or one of its affi liates. DECEMBER 2018 • VOL 219 • NUMBER 12 FEATURES China’s Miners Promote New Era of Openness and Cooperation Major reforms within the mining sector and the government will foster green mines at home and greater investment abroad ....................................42 Defeating the Deleterious Whether at the head of a circuit or scavenging tailings, today’s flotation innovations address challenges presented by declining grades, rising costs and aging plants ..................................................................................52 Staying on Top of -

Our Company Annual Report 2011 a Disciplined Approach a Proven Strategy We Are BHP Billiton, a Leading Global Resources Company

For personal use only Our Company Annual Report 2011 A disciplined approach A proven strategy We are BHP Billiton, a leading global resources company. Our purpose is to create long-term shareholder value through the discovery, acquisition, development and marketing of natural resources. For personal use only BHP Billiton Limited. ABN 49 004 028 077. Registered in Australia. Registered office: 180 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia. BHP Billiton Plc. Registration number 3196209. Registered in England and Wales. Registered office: Neathouse Place, London SW1V 1BH, UK. Each of BHP Billiton Limited and BHP Billiton Plc are members of the BHP Billiton Group, which is headquartered in Australia. Contents 1 Key information 3 4 Board of Directors and information Key 1 1.1 Our business 3 Group Management Committee 104 1.2 Chairman’s Review 4 4.1 Board of Directors 104 1.3 Chief Executive Offi cer’s Report 5 4.2 Group Management Committee 107 1.4 Selected key measures 6 5 Corporate Governance Statement 108 1.5 Risk factors 7 5.1 Governance at BHP Billiton 108 1.6 Forward looking statements 11 5.2 Shareholder engagement 109 2 Information on the Company 12 5.3 Board of Directors 109 2.1 BHP Billiton locations 12 5.4 Board of Directors – Review, Information on the Company 2 2.2 Business overview 14 re-election and renewal 115 2.2.1 History and development 14 5.5 Board Committees 117 2.2.2 Petroleum Customer Sector Group 14 5.6 Risk management 124 2.2.3 Aluminium Customer Sector Group 21 5.7 Management 125 2.2.4 Base Metals Customer -

Feature Feature Major Wa Mining Projects

FEATURE FEATURE MINING OUTLOOK Construction workers needed for major Major WA mining projects MINING OUTLOOK 27,000 WA resources projects 2014-15 Source: Pitcrew Port Hedland Pardoo Rio Tinto rail MAJOR WA MINING PROJECTS Dampier Cape Lambert Iron Bridge Mt Dove Rio Tinto mine Completed in past year Balla Balla Abydos (Forge Resources) BHP rail Karara Mining Karara project $2.6bn Mid West Production ramp-up proceeding Sino Iron Wodgina Rio Tinto Hope Downs 4 mine $2.1bn Pilbara First production in H1 2013, ramping up to 15mtpa BHP mine Rio Tinto Marandoo mine expansion $1.1bn Pilbara Production will be sustained at 15mtpa for 16 further years Mt Webber McPhee Creek FMG rail Fortescue Metals Christmas Creek 2 expansion $US1.0bn Pilbara Completed in June 2013 quarter Fortescue Metals Port Hedland port expansion $US2.4bn Pilbara Fourth berth and support infrastructure opened in Aug 2013 Pannawonica FMG mine Atlas Iron Mt Dove mine development n/a Pilbara Production commenced in Dec 2012 Hancock proposed rail Atlas Iron Abydos mine development n/a Pilbara First haulage in Aug 2013, ramping up to 2-3mtpa Solomon Atlas Iron Utah Point 2 stockyard n/a Pilbara Largely complete and now ready to receive ore Hancock mine Hub Christmas Creek Rio Tinto Argyle Diamonds underground mine $US2.2bn Kimberley Production commenced in H1 2013 and is ramping up Buckland (Iron Ore Holdings) Cloudbreak Mineral Resources Sandfire Resources DeGrussa copper mine $US384m Mid West Ramp-up to nameplate production nearing completion Koodaideri Roy Hill Atlas Iron Construction -

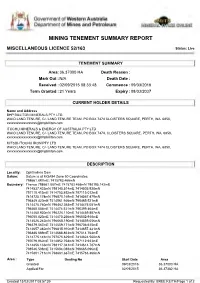

Mining Tenement Summary Report

Government of Western Australia Department of Mines and Petroleum MINING TENEMENT SUMMARY REPORT MISCELLANEOUS LICENCE 52/163 Status: Live TENEMENT SUMMARY Area: 36.37000 HA Death Reason : Mark Out : N/A Death Date : Received : 02/09/2015 08:33:48 Commence : 09/03/2016 Term Granted : 21 Years Expiry : 08/03/2037 CURRENT HOLDER DETAILS Name and Address BHP BILLITON MINERALS PTY LTD WAIO LAND TENURE, C/- LAND TENURE TEAM, PO BOX 7474 CLOISTERS SQUARE, PERTH, WA, 6850, [email protected] ITOCHU MINERALS & ENERGY OF AUSTRALIA PTY LTD WAIO LAND TENURE, C/- LAND TENURE TEAM, PO BOX 7474, CLOISTERS SQUARE, PERTH, WA, 6850, [email protected] MITSUI-ITOCHU IRON PTY LTD WAIO LAND TENURE, C/- LAND TENURE TEAM, PO BOX 7474 CLOISTERS SQUARE, PERTH, WA, 6850, [email protected] DESCRIPTION Locality: Ophthalmia Dam Datum: Datum is at MGA94 Zone 50 Coordinates. 798661.887mE; 7415783.466mN Boundary: Thence 798661.887mE 7415783.466mN 798195.142mE 7414537.433mN 798145.514mE 7414505.938mN 797110.415mE 7414753.892mN 797115.012mE 7414725.174mN 796870.169mE 7414567.479mN 796849.420mE 7414561.946mN 796465.521mE 7414475.760mN 796462.363mE 7414475.051mN 796460.004mE 7414474.521mN 796399.464mE 7414460.930mN 796226.110mE 7414459.887mN 796050.820mE 7414470.256mN 796032.918mE 7414526.242mN 796068.190mE 7414559.056mN 796379.567mE 7414559.171mN 796736.615mE 7414657.382mN 796815.910mE 7414657.431mN 796886.689mE 7414688.863mN 797014.764mE 7414775.141mN 797075.629mE 7414824.500mN 797079.962mE 7414852.758mN 797112.933mE 7414856.133mN -

Iron Ore Briefing and Western Australia Iron Ore Site Tour

BHP Billiton Limited BHP Billiton Plc 171 Collins Street Neathouse Place Melbourne Victoria 3000 Australia London SW1V 1LH UK GPO BOX 86 Tel +44 20 7802 4000 Melbourne Victoria 3001 Australia Fax + 44 20 7802 4111 Tel +61 1300 55 47 57 Fax +61 3 9609 3015 bhpbilliton.com bhpbilliton.com 6 October 2014 To: Australian Securities Exchange cc: London Stock Exchange New York Stock Exchange JSE Limited IRON ORE BRIEFING AND WESTERN AUSTRALIA IRON ORE SITE TOUR Jimmy Wilson, President, Iron Ore will host an Iron Ore briefing and a Western Australia Iron Ore (WAIO) site tour on Monday 6 October 2014, Tuesday 7 October 2014 and Wednesday 8 October 2014. A copy of the materials to be presented is attached. Further information on BHP Billiton can be found at: www.bhpbilliton.com. Nicole Duncan Company Secretary For personal use only NEWS RELEASE Release Time IMMEDIATE Date 6 October 2014 Number 17/14 COST REDUCTIONS AND CAPITAL EFFICIENT GROWTH AT WAIO BHP Billiton President Iron Ore, Jimmy Wilson, today announced plans to cut unit costs at Western Australia Iron Ore (WAIO) by at least 25 per cent and the potential to increase capacity there by 65 million tonnes per year at a very low capital cost. Mr Wilson outlined BHP Billiton’s view of the long-term supply and demand trends in the iron ore market. “We continue to see healthy demand growth for iron ore in the mid-term as Chinese steel production is expected to increase by approximately 25 per cent to between 1.0 and 1.1 billion tonnes in the early to mid-2020s,” he said. -

Initial Public Offering (“IPO”) of Ordinary Shares in Mcaleese

McAleese Group Prospectus For personal use only Prospectus JOINT LEAD MANAGERS McAleese Limited ACN 156 354 068 Important Notices Offer and unknown risks, including the risks set out in The Shares have not been, and will not be, The Offer contained in this Prospectus is an Section 5, many of which are beyond the control registered under the US Securities Act or the invitation to acquire fully paid ordinary shares in of McAleese Group and the Directors. McAleese securities laws of any state or other jurisdiction in McAleese Limited (ACN 156 354 068) (“McAleese Group and the Directors cannot and do not give the United States and may not be offered or sold, Group”) (“Shares”). any assurance that the results, performance or directly or indirectly, in the United States unless the achievements expressed or implied by the forward Shares are registered under the US Securities Act, Lodgement and Listing looking statements contained in this Prospectus or an exemption from the registration requirements This Prospectus is dated 12 November 2013 and will actually occur and investors are cautioned of the US Securities Act and any other applicable was lodged with the Australian Securities and not to place undue reliance on these forward securities laws is available. Investment Commission (“ASIC”) on that date. looking statements. Except where required by law, See Section 7.7 for more detail on selling Neither ASIC nor the Australian Securities Exchange McAleese Group has no intention of updating or (“ASX”) takes any responsibility for the contents restrictions that apply to the offer and sale revising forward looking statements, or publishing of Shares in jurisdictions outside of Australia. -

Notice of Meeting for Approval of the Proposed Transaction with BBIG

30 January 2020 ASX ANNOUNCEMENT Notice of Meeting for approval of the Proposed Transaction with BBIG Flinders Mines Limited (ASX:FMS) (Flinders) is pleased to announce the release of the attached notice of meeting, including an explanatory memorandum and independent expert's report (Notice of Meeting) in respect of an Extraordinary General Meeting (EGM) to consider the proposed transaction with BBI Group Pty Ltd (BBIG) to form an incorporated joint venture for the development of Flinders' Pilbara Iron Ore Project (PIOP), as announced on 28 November 2019 (Proposed Transaction). The Proposed Transaction represents the outcome of extensive commercial negotiations conducted by the Company’s independent PIOP Infrastructure Committee with BBIG to provide an infrastructure solution, facilitate the development of the PIOP and provide a pathway to market. Vote in favour of the Proposed Transaction The Independent Flinders Directors (Neil Warburton, The Hon. Cheryl Edwardes AM and James Gurry) unanimously recommend that Flinders shareholders vote in favour of the Proposed Transaction in the absence of a superior proposal. The Independent Flinders Directors appointed Grant Samuel as independent expert to consider and provide an opinion on the Proposed Transaction. The independent expert has concluded that the Proposed Transaction is fair and reasonable to non-associated Flinders shareholders, i.e. those shareholders other than TIO (NZ) Pty Ltd (TIO), Flinders’ largest shareholder and also a shareholder of BBIG. TIO will also be excluded from voting in favour of the Proposed Transaction. Ms Edwardes, Deputy Chair and Chair of Flinders’ PIOP Infrastructure Committee, said: “I am very pleased with the outcome of the negotiations with BBIG. -

WA Iron Ore Profile – January 2019 1

Western Australia Iron Ore Profile January 2019 THE WORLD IRON ORE MARKET Major global iron ore producers: 2017 Western Australia is the largest iron ore producer and exporter in the world, Western Australia accounting for 38% of global production Brazil and 56% of global seaborne exports in China 2017. Brazil is the second largest iron ore India producer and exporter in the world, Russia accounting for 17% of global production South Africa and 23% of global seaborne exports in 2017. Ukraine China (14%), India (7%) and Russia (5%) Iran are major global iron ore producers, but USA retain most of their production for Canada domestic steel production. China’s iron ore production rose 1% to 0Mt 200Mt 400Mt 600Mt 800Mt 1000Mt 302 million tonnes in 2017, following three Exported Consumed domestically/stockpiled successive years of decline since peaking Source: CRU, Iron Ore Market Outlook Statistical Review. at 506 million tonnes in 2013. China’s iron ore demand 1200Mt China accounted for 72% of global iron ore seaborne imports and 50% of global crude steel production in 2017. 1000Mt China’s iron ore imports rose 5% to 1,061 million tonnes in 2017. 800Mt China’s crude steel production fell 3% to 846 million tonnes in 2017. Around 1.4 600Mt tonnes of iron ore is used to make one tonne of crude steel. 400Mt CRU forecasts China’s iron ore imports to fall gradually over the next few years to 200Mt 1,022 million tonnes in 2022. Japan and South Korea were the next 0Mt 2005 2008 2011 2014 2017 2020 largest global iron ore importers in 2017. -

The Blenheim Report

The Blenheim Report CONFIDENTIAL INTELLIGENCE REPORT IRON ORE PRODUCERS JUNE 2013 Blenheim Partners Pty Ltd ABN 21 160 009 236 | Level 5, 17-19 Bridge Street, Sydney NSW 2000 Australia | p +61 2 9253 0950 | w blenheimpartners.com Blenheim Partners is a premier international Executive Search and Board Advisory consulting firm. Our team have acted at Board and CEO level for the ASX100, FTSE100 and Asian listed companies, as well as for a range of mid-cap and smaller businesses both publicly and privately owned. We have come together bonded by a singular purpose of providing a search and consulting model that ensures our clients achieve the optimal outcome through a highly dedicated and accountable partnership. Our goal is to help our clients deliver superior performance by maximising the composition of their senior management teams. Blenheim combines the quality, structure and process of a large firm with the flexibility, creativity and relationship focus of a boutique. Our work falls into three areas: Top Level Executive Search, Non-Executive Search and Consulting. We only partner with 1 company per sector to ensure our clients receive sector expertise and complete market coverage We do not have conflicts of interest or “off limits” restrictions as a result of our partnering model We support our clients long term planning capability with our actionable intelligence We provide Assessment and a 90 day On Boarding Programme with all searches We allow our clients to determine the fee tied to meeting and exceeding expectations We achieve diversity of thought and innovation We have “no limitations” in the pursuit of excellence Confidentiality This report and the information contained in it are confidential and proprietary information belonging to Blenheim Partners. -

MAC – Yandi Rail Spur Inert Landfill Licence Application Supporting Documentation (Including Information Relating to Attachments 1 to 10)

MAC – Yandi Rail Spur Inert Landfill Licence Application Supporting Documentation (Including Information relating to Attachments 1 to 10) September 2018 Jimblebar L5415/1988/9 Licence Amendment Supporting Documentation (Including Information relating to Attachments 1 to 10) October 2017 MAC – Yandi Rail Spur Inert Landfill Licence Application Supporting Document Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 2. Project Description .................................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Existing Environment ................................................................................................................................................. 4 4. Environmental Management ...................................................................................................................................... 6 5. Environmental Impact Assessment and Associated Management Strategies ........................................................... 7 6. Heritage ................................................................................................................................................................... 11 7. Community Consultation ......................................................................................................................................... 11 8. Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Arrium Limited Asx Appendix 4E Abn 63 004 410 833 Preliminary Final Report

ARRIUM LIMITED ASX APPENDIX 4E ABN 63 004 410 833 PRELIMINARY FINAL REPORT ARRIUM LIMITED RESULTS FOR ANNOUNCEMENT TO THE MARKET FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2014 Comparison to previous corresponding period (pcp) Movement % Change A$ million Total revenue from ordinary activities up 2.4% to 7,006.6 Profit from ordinary activities after tax attributable up NC* to 205.4 to ordinary equity holders Net profit for the period attributable to ordinary up NC* to 205.4 equity holders * NC = Not comparable Dividends Final Dividend 2014 Interim Dividend 2014 Amount per security 3.0c 6.0c Franked amount per security 0.0c 0.0c Amount per security declared to be conduit 0.0c 0.0c foreign income Total dividend and dividend payment (A$ million) 41.0 81.7 Date Ex-dividend date for Final Dividend 10 September 2014 Record date for determining entitlement to Final Dividend 12 September 2014 Last day to elect to participate in the Dividend Reinvestment Plan (DRP) 15 September 2014 Date payable (on or around) 16 October 2014 Net tangible assets 30 June 2014 30 June 2013 Net Tangible Assets per security ($) 1.29 1.19 For personal use only ARRIUM LIMITED ASX APPENDIX 4E ABN 63 004 410 833 PRELIMINARY FINAL REPORT Details of Associates and Joint Venture Entities Name of associate or joint venture entity Associate or Joint Percentage Percentage Venture Entity holding holding June 2014 June 2013 BOSFA Pty Ltd Joint Venture 50% 50% GenAlta Recycling Inc. Joint Venture 50% 50% Details of entities over which control was gained during the period Name of entity Date Arrium Mining Sales Asia Limited 30 July 2013 Arrium Mining Services Asia Limited 26 July 2013 Moly-Cop Finance UK Limited 19 May 2014 There were no entities over which control was lost during the period. -

BHP OPERATIONAL REVIEW for the YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2021 Note: All Guidance Is Subject to Further Potential Impacts from COVID-19 During the 2022 Financial Year

Release Time IMMEDIATE Date 20 July 2021 Release Number 09/21 BHP OPERATIONAL REVIEW FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2021 Note: All guidance is subject to further potential impacts from COVID-19 during the 2022 financial year. Record production was achieved at Western Australia Iron Ore (WAIO) and Goonyella. Olympic Dam achieved both the highest annual copper production since the acquisition by BHP in 2005 and the highest gold production ever for the operation. Escondida maintained average concentrator throughput at record levels despite a challenging operating environment in Chile as a result of impacts from COVID-19. Petroleum production for the 2021 financial year was slightly above guidance. Full year production guidance for copper, iron ore, metallurgical coal and nickel were delivered, as was revised guidance for energy coal. Full year unit cost guidance(1) expected to be achieved for WAIO, Escondida and Queensland Coal (based on exchange rates of AUD/USD 0.70 and USD/CLP 769). Petroleum unit costs are expected to be slightly better than guidance. New South Wales Energy Coal (NSWEC) unit costs are expected to be marginally above guidance. During the year, we successfully achieved first production at four major development projects, all of which were delivered on or ahead of schedule and on budget. The South Flank iron ore project in Western Australia and the Ruby oil and gas project in Trinidad and Tobago both achieved first production in May 2021. The Atlantis Phase 3 petroleum project and the Spence Growth Option copper project achieved first production in the first half of the 2021 financial year.