The Mineral Industry of Australia in 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WA PORTS Vital Infrastructure for Western Australia's Commodity

WESTERN AUSTRALIA’S INTERNATIONAL RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT MAGAZINE June–August 2006 $3 (inc GST) WA PORTS Vital infrastructure for Western Australia’s commodity exports LNG Keen interest in Browse Basin gas GOLD Major new development plans for Boddington IRON ORE Hope Downs project enters the fast lane Print post approved PP 665002/00062 approved Print post Jim Limerick DEPARTMENT OF INDUSTRY AND RESOURCES Investment Services 1 Adelaide Terrace East Perth, Western Australia 6004 Tel: +61 8 9222 3333 • Fax: +61 8 9222 3862 Email: [email protected] www.doir.wa.gov.au INTERNATIONAL OFFICES Europe European Office • 5th floor, Australia Centre From the Director General Corner of Strand and Melbourne Place London WC2B 4LG • UNITED KINGDOM Tel: +44 20 7240 2881 • Fax: +44 20 7240 6637 Email: [email protected] Overseas trade and investment India — Mumbai In a rare get together, key people who facilitate business via the Western Australian Western Australian Trade Office 93 Jolly Maker Chambers No 2 Government’s overseas trade offices gathered in Perth recently to discuss ways to 9th floor, Nariman Point • Mumbai 400 021 INDIA maximise services for local and international businesses. Tel: +91 22 5630 3973/74/78 • Fax: +91 22 5630 3977 Email: [email protected] All of the Western Australian Government’s 14 overseas offices, with the exception of India — Chennai the USA, were represented by their regional directors. Western Australian Trade Office - Advisory Office 1 Doshi Regency • 876 Poonamallee High Road Kilpauk • Chennai 600 084 • INDIA The event was a huge success with delegates returning home with fresh ideas on how Tel: +91 44 2640 0407 • Fax: +91 44 2643 0064 to overcome impediments and develop and promote trade in, and investment from, their Email: [email protected] respective regions. -

Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254)

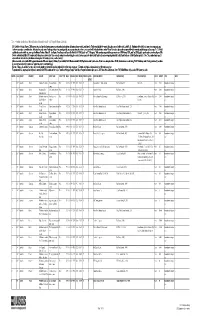

Table1.—Attribute data for the map "Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254). [The United States Geological Survey (USGS) surveys international mineral industries to generate statistics on the global production, distribution, and resources of industrial minerals. This directory highlights the economically significant mineral facilities of Asia and the Pacific. Distribution of these facilities is shown on the accompanying map. Each record represents one commodity and one facility type for a single location. Facility types include mines, oil and gas fields, and processing plants such as refineries, smelters, and mills. Facility identification numbers (“Position”) are ordered alphabetically by country, followed by commodity, and then by capacity (descending). The “Year” field establishes the year for which the data were reported in Minerals Yearbook, Volume III – Area Reports: Mineral Industries of Asia and the Pacific. In the “DMS Latitiude” and “DMS Longitude” fields, coordinates are provided in degree-minute-second (DMS) format; “DD Latitude” and “DD Longitude” provide coordinates in decimal degrees (DD). Data were converted from DMS to DD. Coordinates reflect the most precise data available. Where necessary, coordinates are estimated using the nearest city or other administrative district.“Status” indicates the most recent operating status of the facility. Closed facilities are excluded from this report. In the “Notes” field, combined annual capacity represents the total of more facilities, plus additional -

Kimberley Technology Solutions Pty Ltd Cockatoo Island Multi-User Supply Base EPBC Matters of National Environmental Significance Assessment

Kimberley Technology Solutions Pty Ltd Cockatoo Island Multi-User Supply Base EPBC Matters of National Environmental Significance Assessment June 2017 Table of contents 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Purpose of this Document ...................................................................................................1 1.2 Overview of the Proposal.....................................................................................................1 1.3 The Proponent .....................................................................................................................1 1.4 Location of the Project .........................................................................................................1 2. The Proposal..................................................................................................................................3 2.1 Proposal Justification...........................................................................................................3 2.2 On-shore Developments......................................................................................................3 2.1 Marine Developments..........................................................................................................8 2.2 Staging...............................................................................................................................10 3. Existing environment....................................................................................................................11 -

Our Minerals and Mining Capabilities

KAURNA ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We acknowledge and pay our respects to the Kaurna Just as the minerals sector is central to our nation’s identity people, the original custodians of the Adelaide Plains and prosperity, so it is to the University of Adelaide. and the land on which the University of Adelaide’s Through our world-class research and development campuses at North Terrace, Waite, and Roseworthy expertise, we’ve supported and strengthened Australian are built. We acknowledge the deep feelings of WELCOME attachment and relationship of the Kaurna people mining since 1889; and we will continue to act as a catalyst to country and we respect and value their past, for its success well into the future. present and ongoing connection to the land and As you’ll see in these pages, our relevant expertise and cultural beliefs. The University continues to develop experience—coordinated and focused through our Institute respectful and reciprocal relationships with all for Mineral and Energy Resources—encompasses every Indigenous peoples in Australia, and with other Indigenous peoples throughout the world. aspect of the minerals value chain. You will also see evidenced here the high value we place on industry collaboration. We believe strong, productive partnerships are essential, both to address the sector’s biggest challenges and maximise its greatest opportunities. An exciting tomorrow is there for the making—more efficient, more productive and environmentally sustainable. We would welcome the chance to shape it with you. Regards, Professor Peter Høj -

IGO Interactive Annual Report 2020

2021 ANNUAL REPORT We believe in a green energy future. IGO Limited is an ASX 100 listed ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Company focused on creating a We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on better planet for future generations by which we operate and on which we work. We recognise their connection to land, waters and culture, and pay our discovering, developing, and delivering respects to their Elders past, present and emerging. products critical to clean energy. We would like to thank Neil Warburton who retired from the IGO Board in FY21 for his significant contribution to IGO over the last five years. WHO WE ARE We are also pleased to welcome two new appointments IGO Limited is an ASX 100 listed Company focused on to the Board, Xiaoping Yang as a Non-executive Director creating a better planet for future generations by discovering, and Michael Nossal as a Non-executive Director who developing, and delivering products critical to clean energy. transitioned to the Chair role on 1 July 2021. As a purpose-led organisation with strong, embedded values and a culture of caring for our people and our stakeholders, We would also like to take this opportunity to thank Peter we believe we are Making a Difference by safely, sustainably Bilbe, who was appointed to the IGO Board in 2009, for his and ethically delivering the products our customers need substantial contribution to the Company. Over his tenure, to advance the global transition to decarbonisation. Peter has overseen the positive transformation of IGO, culminating in the announcement on 30 June 2021 of the Through our upstream mining and downstream processing completion of the transaction with Tianqi Lithium Corporation. -

View Annual Report

2010 Annual Report We expect to triple our production base by 2015. A SOLID BASE A POSITION OF STRENGTH GroA ROBUST PROJwECT PIPELINE th A nickel A copper A copper-gold A nickel project under deposit in the One of the The 8th largest operation in a operation with construction in new Copperbelt world’s major copper mine in growing mining over 30 years mining-friendly located in undeveloped the world jurisdiction of mine life Finland NW Zambia copper deposits Kansanshi Guelb Moghrein Ravensthorpe Kevitsa Sentinel Haquira First Quantum Minerals Ltd. is a growing mining and metals First Quantum currently The Company’s current company engaged in mineral produces LME grade “A” copper approved copper projects are exploration, development cathode, copper in concentrate, expected to increase annual and mining. The Company’s gold and sulphuric acid and is production by at least 45% objective is to become a on track to become a significant by 2015. In addition, later-stage globally diversified nickel producer by 2012. The exploration projects have mining company. Company's current operations the potential to add a further are the Kansanshi copper-gold 500,000 tonnes of annual mine in Zambia and the Guelb copper production. Moghrein copper-gold mine in Mauritania. In 2010, First Quantum produced 323,017 tonnes of copper, 191,395 ounces of gold and generated $2.4 billion of revenues. Unless otherwise noted, all amounts in this report are expressed in United States dollars. 2010 Annual Report In 2010, our operations continued to provide a solid base to support our growth strategy. -

2016-2017 Statement of Corporate Intent Kimberley Ports Authority

2016-2017 Statement of Corporate Intent Kimberley Ports Authority Contents Building a Resilient Kimberley Ports Authority ..................................................................... 2 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 3 2. Strategic Framework .................................................................................................... 4 3. Statutory Framework ................................................................................................... 5 4. Port Characteristics ...................................................................................................... 6 5. Core Strategies ........................................................................................................... 13 6. Key Strategic Areas ..................................................................................................... 15 7. Strategic Actions ........................................................................................................ 17 8. Supporting Actions ..................................................................................................... 21 9. Policy Statements ....................................................................................................... 23 Disclaimer 10. Financial Management .......................................................................................... 25 Kimberley Ports Authority (KPA) has used all reasonable care in the preparation of -

20 September 2011 Company Announcements Office

20 September 2011 Company Announcements Office Australian Securities Exchange Limited Level 4 20 Bridge Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 RE: Thiess wins Fortescue Pilbara Iron Ore mine contract Please find attached a copy of a media release to be issued today by Thiess Pty Ltd, a wholly owned subsidiary of Leighton Holdings Limited. Yours faithfully, A.J. MOIR Company Secretary Thiess Pty Ltd A.C.N. 010 221 486 MEDIA RELEASE A.B.N. 87 010 221 486 Thiess Centre 179 Grey Street South Bank QLD 4101 20 September 2011 Locked Bag 2009 South Brisbane QLD 4101 Australia Telephone (07) 3002 9000 Facsimile (07) 3002 9009 THIESS WINS FORTESCUE PILBARA IRON ORE MINE CONTRACT Thiess has won a major $100 million contract with Fortescue Metals Group for Phase One development works on the Solomon Hub iron ore mine in Western Australia’s Pilbara region. The 18 month contract is for initial pioneering and mine establishment works such as haul roads, stockpile pads and the mining of early ore and waste. The work will establish the Solomon area for long term mining operations. Managing Director Bruce Munro said the contract represents a welcome return to the west for Thiess’ mining business and underlines the importance of Western Australia to Thiess as a whole. “Our Construction and Services businesses have long term client relationships and strong operations in the West and with the substantial iron ore reserves, there are clients we could assist in getting the best out of their mining operations” Mr Munro said. Thiess won the iron ore mine contract in a competitive process, and is now well positioned to bid for further works on the mine development and the main services contract which commences in approximately 12 months. -

Anglogold Ashanti Limited (Anglogold Ashanti) Publishes a Suite of Reports to Record Its Overall Performance Annually

ANNUAL FINANCIAL ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS STATEMENTS 2013 2013 GUIDE TO REPORTING AngloGold Ashanti Limited (AngloGold Ashanti) publishes a suite of reports to record its overall performance annually. The Annual Financial Statements 2013 addresses our statutory reporting requirements. The full suite of 2013 reports for AngloGold Ashanti Limited comprises: Annual Integrated Report 2013, the primary report; Annual Financial Statements 2013; Annual Sustainability Report 2013; and Mineral Resource and Ore Reserve Report 2013. Other reports available for the financial year are the operational and project profiles and country fact sheets. The full suite of 2013 reports have been furnished to the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on Form 6-K. These reports are all available on our annual report portal at www.aga-reports.com. FOR NOTING: The following key parameters should be noted in respect of our reports: Production is expressed on an attributable basis unless otherwise indicated; Unless otherwise stated, $ or dollar refers to US dollars throughout this suite of reports; Group and company are used interchangeably, except for in the group and company annual financial statements; Statement of financial position and balance sheet are used interchangeably; and The company implemented an Enterprise Resource Planning System (ERP), i.e. SAP at all its operations, except for the Continental Africa region. ERP and SAP are used interchangeably. 1 VISION, MISSION AND VALUES To create value for our shareholders, our employees and our business and social partners through safely and responsibly exploring, mining and marketing our products. Our primary focus is gold, but we will pursue value creating opportunities in other minerals where we can leverage our existing assets, skills and experience to enhance the delivery of value. -

ESG Reporting by the ASX200

Australian Council of Superannuation Investors ESG Reporting by the ASX200 August 2019 ABOUT ACSI Established in 2001, the Australian Council of Superannuation Investors (ACSI) provides a strong, collective voice on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues on behalf of our members. Our members include 38 Australian and international We undertake a year-round program of research, asset owners and institutional investors. Collectively, they engagement, advocacy and voting advice. These activities manage over $2.2 trillion in assets and own on average 10 provide a solid basis for our members to exercise their per cent of every ASX200 company. ownership rights. Our members believe that ESG risks and opportunities have We also offer additional consulting services a material impact on investment outcomes. As fiduciary including: ESG and related policy development; analysis investors, they have a responsibility to act to enhance the of service providers, fund managers and ESG data; and long-term value of the savings entrusted to them. disclosure advice. Through ACSI, our members collaborate to achieve genuine, measurable and permanent improvements in the ESG practices and performance of the companies they invest in. 6 INTERNATIONAL MEMBERS 32 AUSTRALIAN MEMBERS MANAGING $2.2 TRILLION IN ASSETS 2 ESG REPORTING BY THE ASX200: AUGUST 2019 FOREWORD We are currently operating in a low-trust environment Yet, safety data is material to our members. In 2018, 22 – for organisations generally but especially businesses. people from 13 ASX200 companies died in their workplaces. Transparency and accountability are crucial to rebuilding A majority of these involved contractors, suggesting that this trust deficit. workplace health and safety standards are not uniformly applied. -

Aussie Mine 2016 the Next Act

Aussie Mine 2016 The next act www.pwc.com.au/aussiemine2016 Foreword Welcome to the 10th edition of Aussie Mine: The next act. We’ve chosen this theme because, despite gruelling market conditions and industry-wide poor performance in 2016, confidence is on the rise. We believe an exciting ‘next act’ is about to begin for our mid-tier miners. Aussie Mine provides industry and financial analysis on the Australian mid-tier mining sector as represented by the Mid-Tier 50 (“MT50”, the 50 largest mining companies listed on the Australian Securities Exchange with a market capitalisation of less than $5bn at 30 June 2016). 2 Aussie Mine 2016 Contents Plot summary 04 The three performances of the last 10 years 06 The cast: 2016 MT50 08 Gold steals the show 10 Movers and shakers 12 The next act 16 Deals analysis and outlook 18 Financial analysis 22 a. Income statement b. Cash flow statement c. Balance sheet Where are they now? 32 Key contributors & explanatory notes 36 Contacting PwC 39 Aussie Mine 2016 3 Plot summary The curtain comes up Movers and shakers The mining industry has been in decline over the last While the MT50 overall has shown a steadying level few years and this has continued with another weak of market performance in 2016, the actions and performance in 2016, with the MT50 recording an performances of 11 companies have stood out amongst aggregated net loss after tax of $1bn. the crowd. We put the spotlight on who these movers and shakers are, and how their main critic, their investors, have But as gold continues to develop a strong and dominant rewarded them. -

The Mineral Industry of Australia in 2012

2012 Minerals Yearbook AUSTRALIA U.S. Department of the Interior February 2015 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF AUSTRALIA By Pui-Kwan Tse Australia was subject to volatile weather in recent years Government Policies and Programs that included heavy rains and droughts. The inclement weather conditions affected companies’ abilities to expand The powers of Australia’s Commonwealth Government are their activities, such as port, rail, and road construction and defined in the Australian Constitution; powers not defined in the repair, as well as to mine, process, manufacture, and transport Constitution belong to the States and Territories. Except for the their materials. Slow growth in the economies of the Western Australian Capital Territory (that is, the capital city of Canberra developed countries in 2012 affected economic growth and its environs), all Australian States and Territories have negatively in many counties of the Asia and the Pacific region. identified mineral resources and established mineral industries. China, which was a destination point for many Australian Each State has a mining act and mining regulations that mineral exports, continued to grow its economy in 2012, regulate the ownership of minerals and the operation of mining although the rate of growth was slower than in previous years. activities in that State. The States have other laws that deal with As a result, Australia’s gross domestic product (GDP) increased occupational health and safety, environment, and planning. at a rate of 3.1% during 2012, which was higher than the All minerals in the land are reserved to the Crown; however, 2.3% rate of growth recorded in 2011.