John Brown's Transformation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Patterns of Unrest in the Springfield Public Schools

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1972 A study of the patterns of unrest in the Springfield public schools. John Victor Shea University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Shea, John Victor, "A study of the patterns of unrest in the Springfield public schools." (1972). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2628. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2628 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UMASS/AMHER^ 3 1 2 b b Q 1 3 S fi 1 ^ ^ All Rights Reserved (e) John V. Shea, Jr. , 1972 /f'57 72- A STUDY OF THE PATTERNS OF UNREST IN THE SPRINGFIELD PUBLIC SCHOOLS A Dissertation Presented By JOHN V. SHEA, JR. Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION June 1972 Major Subject: Administration ) ) A STUDY OF THE PATTERNS OF UNREST IN THE SPRINGFIELD PUBLIC SCHOOLS A Dissertation By John Victor Shea, Jr. Approved as to style and content by: ?. oUL i (Member) y T * ' X ^' h ’ L r* (Member) June 1972 (Month ( Year DEDICATION TO MY BELOVED WIFE, LIZ ACKNOWLEDGMENT This study would not be complete without an expression of appreciation to all who assisted in its development, especially: Dr. -

John Brown, Am Now Quite Certain That the Crimes of This Guilty Land Will Never Be Purged Away but with Blood.”

Unit 3: A Nation in Crisis The 9/11 of 1859 By Tony Horwitz December 1, 2009 in NY Times ONE hundred and fifty years ago today, the most successful terrorist in American history was hanged at the edge of this Shenandoah Valley town. Before climbing atop his coffin for the wagon ride to the gallows, he handed a note to one of his jailers: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.” Eighteen months later, Americans went to war against each other, with soldiers marching into battle singing “John Brown’s Body.” More than 600,000 men died before the sin of slavery was purged. Few if any Americans today would question the justness of John Brown’s cause: the abolition of human bondage. But as the nation prepares to try Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, who calls himself the architect of the 9/11 attacks, it may be worth pondering the parallels between John Brown’s raid in 1859 and Al Qaeda’s assault in 2001. Brown was a bearded fundamentalist who believed himself chosen by God to destroy the institution of slavery. He hoped to launch his holy war by seizing the United States armory at Harpers Ferry, Va., and arming blacks for a campaign of liberation. Brown also chose his target for shock value and symbolic impact. The only federal armory in the South, Harpers Ferry was just 60 miles from the capital, where “our president and other leeches,” Brown wrote, did the bidding of slave owners. -

20 Gallon Galvanized Sheet Steel with Cover

' „ « PAGE EIGHTEEN FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 1966 fianrh^st^r lEorning f^ralb Arcrage Daily Net Preae Run The W oitlier For the Week EiUM ; eC V. a. W esthe ronvm rr M . IN * The Rev. and Mrs. C. Henry Anderson, 157 Pitkin St., have M * ae eeM, About Town returned after two weeks of va World Day Prayer Service 14,126 cationing with relatives at Fort The Chsmlnade Muelcal Club ORANGE HALL Member et tke A «0t Lauderdale, Fla. Pastor Ander Bm eee of OlnidatlM will meet Monday at 8 p.m. In son will preach at Emanuel Set at St. Mary^s March 5 the Federation Room at Center Manchetter^A City of Village Charm Lutheran Church Sunday. Oongreifatlonal Church. "What Inspired Compo9er'.<i Romantic Mrs. Royal J. Gibson, chair-facilities and milk for the Lt. and Mrs. Carl E. Carl.son Aivorttalng ea Page If) PRICE SEVEN CENTO Work.s" will be the theme of the man of evangelism and spiritu young children will be provided. VOL. LXXXIV, NO. 126 (TWELVE PAGES—TV SECTION) MANCHESTER, CONN., SA'TURDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 1965 pro(fram. Mrs. »CharIes Lam- Jr. left yesterday by plane for More than 13S nations in aix Frankfurt, Germany, where Lt. al life at the United Church of oert, president, is in chargre of continents 'will observe March Carlson will be stationed with Christ, West Hartford, will be 5 as World Day of Prayer, now tfie entertainment. The meetingr the U.S. Air Force. The Carl- the guest speaker at the Man BINGO ia open to all women interested in its 79th year. -

Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : a Finding Aid

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids and Research Guides for Finding Aids: All Items Manuscript and Special Collections 5-1-1994 Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives. James Anthony Schnur Hugh W. Cunningham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all Part of the Archival Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives.; Schnur, James Anthony; and Cunningham, Hugh W., "Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid" (1994). Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items. 19. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all/19 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids and Research Guides for Manuscript and Special Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection A Finding Aid by Jim Schnur May 1994 Special Collections Nelson Poynter Memorial Library University of South Florida St. Petersburg 1. Introduction and Provenance In December 1993, Dr. Hugh W. Cunningham, a former professor of journalism at the University of Florida, donated two distinct newspaper collections to the Special Collections room of the USF St. Petersburg library. The bulk of the newspapers document events following the November 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy. A second component of the newspapers examine the reaction to Richard M. Nixon's resignation in August 1974. -

Antislavery Violence and Secession, October 1859

ANTISLAVERY VIOLENCE AND SECESSION, OCTOBER 1859 – APRIL 1861 by DAVID JONATHAN WHITE GEORGE C. RABLE, COMMITTEE CHAIR LAWRENCE F. KOHL KARI FREDERICKSON HAROLD SELESKY DIANNE BRAGG A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2017 Copyright David Jonathan White 2017 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the collapse of southern Unionism between October 1859 and April 1861. This study argues that a series of events of violent antislavery and southern perceptions of northern support for them caused white southerners to rethink the value of the Union and their place in it. John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and northern expressions of personal support for Brown brought the Union into question in white southern eyes. White southerners were shocked when Republican governors in northern states acted to protect members of John Brown’s organization from prosecution in Virginia. Southern states invested large sums of money in their militia forces, and explored laws to control potentially dangerous populations such as northern travelling salesmen, whites “tampering” with slaves, and free African-Americans. Many Republicans endorsed a book by Hinton Rowan Helper which southerners believed encouraged antislavery violence and a Senate committee investigated whether an antislavery conspiracy had existed before Harpers Ferry. In the summer of 1860, a series of unexplained fires in Texas exacerbated white southern fear. As the presidential election approached in 1860, white southerners hoped for northern voters to repudiate the Republicans. When northern voters did not, white southerners generally rejected the Union. -

John Brown, Abolitionist: the Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights by David S

John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights by David S. Reynolds Homegrown Terrorist A Review by Sean Wilentz New Republic Online, 10/27/05 John Brown was a violent charismatic anti-slavery terrorist and traitor, capable of cruelty to his family as well as to his foes. Every one of his murderous ventures failed to achieve its larger goals. His most famous exploit, the attack on Harpers Ferry in October 1859, actually backfired. That backfiring, and not Brown's assault or his later apotheosis by certain abolitionists and Transcendentalists, contributed something, ironically, to the hastening of southern secession and the Civil War. In a topsy-turvy way, Brown may have advanced the anti-slavery cause. Otherwise, he actually damaged the mainstream campaign against slavery, which by the late 1850s was a serious mass political movement contending for national power, and not, as Brown and some of his radical friends saw it, a fraud even more dangerous to the cause of liberty than the slaveholders. This accounting runs against the grain of the usual historical assessments, and also against the grain of David S. Reynolds's "cultural biography" of Brown. The interpretations fall, roughly, into two camps. They agree only about the man's unique importance. Writers hostile to Brown describe him as not merely fanatical but insane, the craziest of all the crazy abolitionists whose agitation drove the country mad and caused the catastrophic, fratricidal, and unnecessary war. Brown's admirers describe his hatred of slavery as a singular sign of sanity in a nation awash in the mental pathologies of racism and bondage. -

May 23, 1898, at 8 O'clock P

PRICE THREE CENTS. MISCELLANEOUS. States Consul George W. when Roosevolt, Hoate an intention to warn all whom it isked to take an active part in the Hi3- may concern that Spain is ready to resist sano-Amerioan war, declined, saying: in the war of any uujustiflablo sohemes of aggression ESCAPE. ‘I was wounded secession a 'rora whatever quarter they may come. TROOPS lozen times and have paid my debt to my These movements 10,000 have reference to the AWFUL TROUBLE. jountry. An American never pays the idea that be to the same debt twice.” Spain may helpful _ MUST power in the event of an SPAIN SUE FOR PEACE. Anglo-Saxon Disease of the Kidneys Are CERVmTMiY lETllii illianoe.” Always Serious. Impossible for Genera to WliTTO PORTLAND, ire Now Tenting at San Disease is Ca- Get Awry. Bright’s w Spanish Admiral Expected Back at Francisco, of the Fwo tarrh Kidneys. Martinique. Her Friends Will Force Her to do Companies Volunteers Assigned to Fort Preble. Pe-ru-na Cures Catarrh, Even MOST DESPERATE of These WITHOUT VOLUNTEERS READY TO Organs. [Copyright, 1898, by the Associated Press) at CONFLICT IN HISTORY. So First St. Pierre, Martinique, May 23.—Ad- Opportunity. Camp Haven, Nlantio, Conn., May 22. START FOR MANILA. —Col. -RU-NA is miral Cervera's squadron, It is reported Burdett, the commandant of this I rendezvous of the Connecticut volunteers something m good authority, will return to these recommend this afternoon received from Capt. Craw- waters to coal. It is known that a turn- ford at Fort New a to everyone. -

President's Daily Diary Collection (Box 78) at the Gerald R

Scanned from the President's Daily Diary Collection (Box 78) at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDENT GERALD R. FORD PLACE DAY BEGAN DATE (Mo., Day, Yr.) THE WHITE HOUSE NOVEMBER 7, 1975 WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME DAY 12:01 a.m. FRIDAY TIME "B :.a ~ ~ ACTIVITY r-~In---'--~O-ut--~ I ! 12:01 12:11 P The President talked with the First Lady. 7:42 The President had breakfast. 8:16 The President went to the Oval Office. 9:14 9:17 R The President talked with his son, Steve. 9:18 The President telephoned Congressman John N. Er1enborn (R-I11inois). The call was not completed. 9:22 The President went to the South Grounds of the White House. 9:22 9:30 The President flew by helicopter from the South Grounds to Andrews AFB, Maryland. For a list of passengers, see APPENDIX "A." 9:35 10:45 The President flew by the "Spirit of '76" from Andrews AFB to Westover AFB, Chicopee, Massachusetts. For a list of passengers, see APPENDIX "B." 10:45 The President was greeted by: Col. Billy M. Knowles, Commander of the 439th Tactical Airlift Wing Lt. Col. Jack P. Fergason, Commander of the 439th Combat Support Group Edward P. Ziemba, Mayor of Chicopee, Massachusetts William Sullivan, Mayor of Springfield, Massachusetts Lisa Chabasz, Little Miss Massachusetts 10:55 11:15 The President motored from Westover AFB to the Baystate West Hotel, 1500 Main Street, Springfield, Massachusetts. He was accompanied by: John A. Volpe, Ambassador from the U.S. -

Appendix File 1984 Continuous Monitoring Study (1984.S)

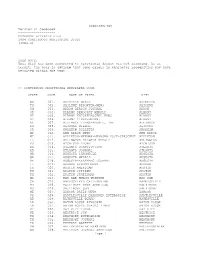

appcontm.txt Version 01 Codebook ------------------- CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE 1984 CONTINUOUS MONITORING STUDY (1984.S) USER NOTE: This file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As as result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. >> CONTINUOUS MONITORING NEWSPAPER CODE STATE CODE NAME OF PAPER CITY WA 001. ABERDEEN WORLD ABERDEEN TX 002. ABILENE REPORTER-NEWS ABILENE OH 003. AKRON BEACON JOURNAL AKRON OR 004. ALBANY DEMOCRAT-HERALD ALBANY NY 005. ALBANY KNICKERBOCKER NEWS ALBANY NY 006. ALBANY TIMES-UNION, ALBANY NE 007. ALLIANCE TIMES-HERALD, THE ALLIANCE PA 008. ALTOONA MIRROR ALTOONA CA 009. ANAHEIM BULLETIN ANAHEIM MI 010. ANN ARBOR NEWS ANN ARBOR WI 011. APPLETON-NEENAH-MENASHA POST-CRESCENT APPLETON IL 012. ARLINGTON HEIGHTS HERALD ARLINGTON KS 013. ATCHISON GLOBE ATCHISON GA 014. ATLANTA CONSTITUTION ATLANTA GA 015. ATLANTA JOURNAL ATLANTA GA 016. AUGUSTA CHRONICLE AUGUSTA GA 017. AUGUSTA HERALD AUGUSTA ME 018. AUGUSTA-KENNEBEC JOURNAL AUGUSTA IL 019. AURORA BEACON NEWS AURORA TX 020. AUSTIN AMERICAN AUSTIN TX 021. AUSTIN CITIZEN AUSTIN TX 022. AUSTIN STATESMAN AUSTIN MI 023. BAD AXE HURON TRIBUNE BAD AXE CA 024. BAKERSFIELD CALIFORNIAN BAKERSFIELD MD 025. BALTIMORE NEWS AMERICAN BALTIMORE MD 026. BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE ME 027. BANGOR DAILY NEWS BANGOR OK 028. BARTLESVILLE EXAMINER-ENTERPRISE BARTLESVILLE AR 029. BATESVILLE GUARD BATESVILLE LA 030. BATON ROUGE ADVOCATE BATON ROUGE LA 031. BATON ROUGE STATES TIMES BATON ROUGE MI 032. BAY CITY TIMES BAY CITY NE 033. BEATRICE SUN BEATRICE TX 034. BEAUMONT ENTERPRISE BEAUMONT TX 035. BEAUMONT JOURNAL BEAUMONT PA 036. -

Transnational Finnish Mobilities: Proceedings of Finnforum XI

Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen This volume is based on a selection of papers presented at Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) the conference FinnForum XI: Transnational Finnish Mobili- ties, held in Turku, Finland, in 2016. The twelve chapters dis- cuss two key issues of our time, mobility and transnational- ism, from the perspective of Finnish migration. The volume is divided into four sections. Part I, Mobile Pasts, Finland and Beyond, brings forth how Finland’s past – often imagined TRANSNATIONAL as more sedentary than today’s mobile world – was molded by various short and long-distance mobilities that occurred FINNISH MOBILITIES: both voluntarily and involuntarily. In Part II, Transnational Influences across the Atlantic, the focus is on sociocultural PROCEEDINGS OF transnationalism of Finnish migrants in the early 20th cen- tury United States. Taken together, Parts I and II show how FINNFORUM XI mobility and transnationalism are not unique features of our FINNISH MOBILITIES TRANSNATIONAL time, as scholars tend to portray them. Even before modern communication technologies and modes of transportation, migrants moved back and forth and nurtured transnational ties in various ways. Part III, Making of Contemporary Finn- ish America, examines how Finnishness is understood and maintained in North America today, focusing on the con- cepts of symbolic ethnicity and virtual villages. Part IV, Con- temporary Finnish Mobilities, centers on Finns’ present-day emigration patterns, repatriation experiences, and citizen- ship practices, illustrating how, globally speaking, Finns are privileged in their ability to be mobile and exercise transna- tionalism. Not only is the ability to move spread very uneven- ly, so is the capability to upkeep transnational connections, be they sociocultural, economic, political, or purely symbol- ic. -

The Subject of My Paper Is on the Abolitionist Movement and Gerrit Smith’S Tireless Philanthropic Deeds to See That Slavery Was Abolished

The subject of my paper is on the Abolitionist movement and Gerrit Smith’s tireless philanthropic deeds to see that slavery was abolished. I am establishing the reason I believe Gerrit Smith did not lose his focus or his passion to help the cause because of his desire to help mankind. Some historians failed to identify with Smith’s ambition and believed over a course of time that he lost his desire to see his dream of equality for all people to be realized. Gerrit Smith was a known abolitionist and philanthropist. He was born on March 6, 1797 in Utica, New York. His parents were Peter Smith and Elizabeth Livingston. Smith’s father worked as a fur trader alongside John Jacob Astor. They received their furs from the Native Americans from Oneida, Mohawk, and the Cayuga tribes in upstate New York.1 Smith and his family moved to Peterboro, New York (Madison County) in 1806 for business purposes. Gerrit was not happy with his new home in Peterboro.2 Smith’s feelings towards his father were undeniable in his letters which indicated harsh criticism. It is clear that Smith did not have a close bond with his father. This tense relationship with his father only made a closer one with his mother. Smith described him to be cold and distant. The only indication as to why Smith detested his father because he did not know how to bond with his children. Smith studied at Hamilton College in 1814. This was an escape for Smith to not only to get away from Peterboro, but to escape from his father whom he did not like. -

Monopoly & King

A READER THE LIBERTARIANISM.ORG READER SERIES INTRODUCES THE MAJOR IDEAS AND THINKERS IN THE LIBERTARIAN TRADITION. Who Makes & King Mob Monopoly History Happen? From the ancient origins of their craft, historians have used their work to defend established and powerful interests and regimes. In the modern period, though, historians have emphasized the agency and impact of everyday, average people—common people—without access to conventional political power. Monopoly & King Mob provides readers with dozens of documents from the Early Modern and Modern periods to suggest that the best history is that which accounts for change both “from above” and “from below” in the social hierarchy. When we think of history as the grand timeline of states, politicians, military leaders, great business leaders, and elite philosophers, we skew our view of the world and our ideas about how it works. ANTHONY COMEGNA is the Assistant Editor for Intellectual History at Anthony Comegna Anthony Libertarianism.org and the Cato Institute. He received an MA (2012) and PhD (2016) in Atlantic and American history from the University of Pittsburgh. He produces historical content for Libertarianism.org regularly and is writer/ host of the Liberty Chronicles podcast. $12.95 DESIGN BY: SPENCER FULLER, FACEOUT STUDIO COVER IMAGE: THINKSTOCK Monopoly and King Mob Edited by Anthony Comegna CATO INSTITUTE WASHINGTON, D.C. 109318_FM_R2.indd 3 7/24/18 10:47 AM Copyright © 2018 by the Cato Institute. All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-944424-56-5 eISBN: 978-1-944424-57-2 Printed in Canada. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available. 109318_FM_R4.indd 4 25/07/2018 11:38 PM TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: AMERICAN HISTORY, ABOVE AND BELOW .