Lakewood, Colorado October 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAMPUS MAP a - Boettcher Auditorium

A B C D E F G H I LEGEND ACADEMIC BUILDINGS B 1 Ammi Hyde Building D-8 U C H 2 Boettcher West D-7 T EL CAMPUS MAP A - Boettcher Auditorium BO 1 U University of Denver 3 Chambers Center for the Advancement of Women B-3 LE VA Light Rail Station 4 Craig Hall B-5 R 54 D 5 Daniels College of Business F-5 6 English Language Center I-3 7 Fisher Early Learning Center A-4 8 Frontier Hall B-5 9 Iliff School of Theology Campus E/F-6 E. COLORADO AVE 10 Johnson-McFarlane Hall B-6 A - Theatre: Black Box Studio & White Box Studio 11 Knoebel School of Hospitality Management C-5 12 Knudson Hall F-7 13 Margery Reed Building F-5 33 14 Mass Communications E-8 15 Metallurgy E-8 2 16 Newman Center for the Performing Arts/Lamont School of Music F-7 60 A - Trevorrow Hall 53 B - Hamilton Recital Hall C - Gates Concert Hall D - Byron Theatre SOUTH WILLIAMS ST SOUTH HIGH ST BUCH TEL BO 17 Olin Hall D-7 61 ULEVA RD 18 Physics Building D-8 EAST JEWELL AVE 48 EAST JEWELL AVE EAST JEWELL AVE 19 Ricketson Law Building E-4 59 20 Ricks Center for Gifted Children F-4 21 Ritchie School for Engineering & Computer Science E-7 22 Ruffatto Hall B-4 55 58 23 Seeley Mudd Science Building D-7 24 Shwayder Art Building D-3 24A A - Nagel Art Studios 3 25 Sie International Relations Complex D-6 A - Sié Chéou-Kang Center K 6 71 26 Sturm Hall C-4 3 24 27 Wesley Hall D-7 35 OTHER BUILDINGS/FACILITIES 28 Academic Office Annex E-8 SOUTH YORK ST SOUTH YORK EAST ASBURY AVE EAST ASBURY AVE 29 Anderson Academic Commons E-5 A - Main Library 26 44 30 Aspen Hall C-6 38 31 Buchtel Bungalow I-5 -

History of Arapahoe County

History of Arapahoe County Arapahoe County was named for the Arapaho Indians, one of the In the late 1820s, trappers searched larger tribes of plains Indians, who along with the Cheyenne occupied this region for beavers to supply Arapahoe County east of the foothills running into what is now western the great demand for mens beaver Kansas. Arapahoe County is Colorado’s first county, since almost hats. In the late 1830s and 1840s, half of the entire area now Colorado was Arapahoe County of the the demand shifted to buffalo Kansas territory. In 1861, when Kansas was made a state, Colorado skins. In 1832, the first trading was made a territory with Arapahoe County as one of the 17 original post on the South Platte River was counties. built on Cherry Creek, which was then part of Arapahoe County. The original Arapahoe County was 30 miles wide and extended from Sheridan Boulevard, the present western boundary of Denver, Adams In 1848, gold prospectors on and Arapahoe counties to the Kansas border. This peculiar shape was their way to California stopped in due to the practice of giving counties with large amounts of plains Colorado long enough to pan its territory at least some of the foothill territory where there was water streams. They found gold on West for mining and irrigation. Even though Arapahoe County did not Dartmouth Avenue, just west of reach the foothills, the streams running from the mountains supplied Englewood where Dry Creek flows water. As settlers came in and took up lands on the eastern portions into the Platte River. -

Agenda Regular Meeting of the City Council City of Lakewood, Colorado Virtual Meeting February 22, 2021 7:00 P.M

AGENDA REGULAR MEETING OF THE CITY COUNCIL CITY OF LAKEWOOD, COLORADO VIRTUAL MEETING FEBRUARY 22, 2021 7:00 P.M. To watch the Council meeting live, please use either one of the following links: City of Lakewood Website: https://www.Lakewood.org/CouncilVideos or Lakewood Speaks: https://lakewoodspeaks.org/ Phone Number for Public Comment: 1-669-900-9128 Webinar ID: 964 1044 5595 (press # after entering the webinar id then press # once more to join the meeting) Press *9 to Request to Speak (You will be prompted when to speak. After speaking, you can hang up or hold to speak on a different agenda item) Press *6 to Unmute The City of Lakewood does not discriminate on the basis of race, age, national origin, color, creed, religion, sex, sexual orientation or disability in the provision of services. People with disabilities needing reasonable accommodation to attend or participate in a City service program, can call 303-987-7080 or TDD 303-987-7057. Please give notice as far in advance as possible so we can accommodate your request. ITEM 1 – CALL TO ORDER ITEM 2 – ROLL CALL ITEM 3 – PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE ITEM 4 – PUBLIC COMMENT Anyone who would like to address the Council on any matter other than an agenda item will be given the opportunity. Speakers should limit their comments to three minutes. ITEM 5 – EXECUTIVE REPORT CITY MANAGER CONSENT AGENDA ORDINANCES ON FIRST READING February 22, 2021 Page 2 (Ordinances are on first reading for notice and publication only; public hearings are held on second reading) ITEM 6 – RESOLUTION 2021-8 – ENDORSING -

1 DISTRICT COURT, CITY and COUNTY of DENVER, COLORADO 1437 Bannock Street Denver, CO 80202 the PEOPLE of the STATE of COLORADO

DISTRICT COURT, CITY AND COUNTY OF DENVER, COLORADO 1437 Bannock Street Denver, CO 80202 THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF COLORADO, v. Jose Roberto MORENO-OLIVAS a/k/a PAUL Victor Antonio BAUTISTA-CERVANTES a/k/a NEGRI Jesus Alfredo VALDEZ-LEON a/k/a ALFREDO Baltazar IBARRA-ALVAREZ a/k/a IBARRA Gildardo VALDEZ-CRUZ a/k/a LAGRIMAS Miriam RIVERA Tawnia WHITE Denise RIVERA-REYES Dolores IBARRA-ESPINOZA Jose Ignacio VALDEZ-SOLIS a/k/a Jesus URIAS-LOPEZ a/k/a PELON Anakaren PEREZ Janett SANCHEZ-RUIZ Adiel ACOSTA-LEYVA Karla VILLA-CEBALLOS Maximilliano ACOSTA Samuel QUINONEZ-HERRERA FNU LNU a/k/a NARICLES Omar BAUTISTA-CUEVAS Alfredo NUNEZ-TARANGO Ivan ABOYTE-VALDEZ FNU LNU a/k/a Unidentified Male #1207 Jesus Alberto LOPEZ-MEDINA Ossler MARQUEZ-GUZMAN a/k/a OLDER Erubiel IBARRA-ALVAREZ a/k/a HUACHE FNU LNU a/k/a Unidentified Male #5123 Jesus BARBA-OCHOA Ivan Felix QUINTERO a/k/a CHAYANNE Gerardo MURILLO a/k/a GERA Jose Luis SALAS-LUGO a/k/a CABIN Eladio MORENO-OLIVAS a/k/a LAYO Jose Luis QUINTERO-SOLANO Jaziel QUINTERO-SOLANO Defendants. COURT USE ONLY 1 PHILIP J. WEISER, Attorney General Case No: ANNEMARIE L. BRAUN* Senior Assistant Attorney General GJ Case No.: 20CR01 Registration Number: 39877 ALISON CONNAUGHTY* Ctrm: 259 Senior Assistant Attorney General Registration Number: 42548 1300 Broadway, 9th Floor Denver, CO 80203 720-508-6701 *Counsel of Record COLORADO STATE GRAND JURY INDICTMENT – SUPERSEDING 2-11-21 Of the 2020-2021 term of the Denver District Court in the year 2021; 2020- 2021 Colorado State Grand Jurors, chosen, selected and sworn -

2020 City of Denver Creative Economy Report with Initial Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis

2020 City of Denver Creative Economy Report with Initial Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis Lisa Gedgaudas Program Administrator, Create Denver Denver Arts & Venues, City of Denver Prepared by: Dr. Michael Seman Colorado State University LEAP Institute for the Arts Regional Economic Development Institute Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. ii Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 Creative Industries Employment ........................................................................................ 1 Creative Occupations Employment .................................................................................... 3 Rising Regional Housing Costs and Creative Occupations ...................................... 4 Creative Industries Revenue ............................................................................................... 6 Initial Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis ................................................................................. 7 Background ............................................................................................................. 7 Impacts .................................................................................................................... 8 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 9 Acknowledgements -

I-25 Central Planning and Environmental Linkages (PEL) Study

Existing Conditions Assessment I-25 Central Planning and Environmental Linkages (PEL) Study 2829 W. Howard Pl. Denver, CO 80204 [email protected] i25centralpel.codot.us This page intentionally left blank. Existing Conditions Assessment Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Study Location and Description ........................................................................................................ 1 Public and Stakeholder Engagement ............................................................................................... 3 Feedback Received To-Date ...................................................................................................... 5 Transportation Planning Context ....................................................................................................... 7 The History of I-25 Central ............................................................................................................... 7 Existing Land Use Context ............................................................................................................... 7 Section 1: 20th Street to Colfax Avenue ..................................................................................... 8 Section 2: Colfax Avenue to US 6/6th Avenue ............................................................................ 8 Section 3: US 6/6th Avenue to Santa Fe Drive/US 85 ............................................................. -

Adams County, Colorado Districts Providing Water and Sanitation Service

Adams County, Colorado Districts Providing Water and Sanitation Service WELD R t E ve S E Bridge St E 160th A D t (!7 L k S r U o y l l Y O o B H Bromley Ln E 152nd Ave d d d R R R t t y l t S s n d l d i e o S c v R d t l i v t e r a a B n b n c a h u c u e e Z i l H D 85 w u o b o L ¤£ P Q a m E P I s F 25 S E 136th Ave e M ¨¦§ y O 76 a H O d ¨¦§ R R B E 128th Ave s 470 n )" i k t a E 120th Ave W t d S R n s o r r e u E 112th Ave d b t v H l S m B a a o h y d a C l a Denver International Airport r e E 104th Av a o 79 l ! m ( i o H C E 96th Ave ER NV (!2 DE N O E 88th A ve S R d E v l W 84th Ave F B F n E Rocky Mountain Arsenal d a J R d 36 i National Wildlife Refuge r ¤£ y t e e l h S 224 k S E 72nd Ave c W 72nd Ave n (! u o t t B S g n s i o h c s E 64th Ave e a 270 P W ¨¦§ E 58th Ave E 56th Ave d 85 d R R ¤£ d r n e R o w s n E 48th Ave 2 o d (! a T d u h R g H d 70 a k R n § c ¨¦ o b a b 225 u M l r a ¨¦§ C H n Palmer Av e u ve d G E 26th Ave x A fa R E Col h t 79 i (! r n ARAPAHOE P e Hwy 36 Adams County Buisness Soloutions Group 4430 South Adams County Parkway, 1st Floor 0 0.5 1 2 3 4 5 Water and Sanitation District Brighton, CO 80601 Tel: 720.523.6800 DISTRICT Box Elder Water and Bromley Park Metro Crestview Water and Greatrock North Water Horse Creek Metro North Washington Water Riverdale Peaks II Metro South Beebe Draw Metro www.adcogov.org/gis Miles Aberdeen Metro District 1 Sanitation District 6 Sanitation and Sanitation District and Sanitation District District Aberdeen Metro District 2 Brighton Crossing Metro Buffalo Ridge -

COMMUNITY PROFILE Boulder COLORADO

287 Town of ERIE Fort Collins Erie 25 2019 COMMUNITY PROFILE Boulder COLORADO 36 76 Situated in the heart of Colorado’s major economic 470 Northwest and population centers and in close proximity to Parkway world-class research and academic institutions, Erie is a full-service community that provides Denver International state of the art infrastructure and support to our Airport (DEN) corporate and retail business partners. Denver ERIE AT A GLANCE 52 Population - 2019 28,308 287 Town Hall Median Age 37 25 Erie Police Station Median Household Income $116,860 & Municipal Court Erie Community Library Planning Area Square Miles 48 Erie Community Center Erie Parkway Incorporated Square Miles 19.8 Acres of Parks & Open Space 300 Arapahoe Road Budget - 2019 $115,712,300 Erie Municipal Airport County Line Road Line County Population Estimate - 2032 34,717 7 Number of Households 9,912 Northwest Parkway 2019 Town of Erie Mill Levies: General Operating Funds 7.288 The Town of Erie is located in Boulder and Weld Trails & Natural Areas Acquisition 4.000 Counties, just west of I-25 for easy access to I-70, Denver International Airport (DEN) and Colorado’s Erie Community Center Construction Bond 3.252 entire Front Range. Erie’s planning area spans 48 square miles, extending from the north side of State Public Safety Building Highway 52 south to State Highway 7, and between Construction Bond 0.550 US 287 on the west and Interstate 25 to the east. Total 15.1 • 35 Minutes to DEN Airport Services • 25 Minutes to Denver Police, Water, Sewer, Street, Storm -

Adams County Community Needs Assessment Analysis of Existing Research Report

ADAMS COUNTY COMMUNITY NEEDS ASSESSMENT ANALYSIS OF EXISTING RESEARCH REPORT PREPARED BY: ABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................1 METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................................................................1 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS .....................................................................................................................................2 MACRO-LEVEL FORCES IMPACTING ADAMS COUNTY ................................................................................5 A SNAPSHOT OF ADAMS COUNTY....................................................................................................................9 INCOME DISTRIBUTION .................................................................................................................................9 POVERTY...........................................................................................................................................................9 EMPLOYMENT PATTERNS............................................................................................................................10 INDUSTRIES IN ADAMS COUNTY................................................................................................................11 EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT.....................................................................................................................12 -

Legal Resources: Custody & Divorce

Legal Resources: Custody & Divorce Jefferson County Jefferson County Domestic Clerk 720-772-2510 Can answer questions about filing a new case Most clinics require participants to bring appropriate forms, Self Help Desk which can be found at 720-772-2501 www.courts.state.co.us (Click 100 Jefferson County Pkwy, Golden, CO 80401 Room 1050 “Forms, then “Domestic/Family”) Assistance with general questions, court forms, resource referral, Jefferson County - page 1-2 policies and procedures, list of discounted attorneys and legal clinics as well as information about divorce/legal separation/custody. Other Counties (serving all areas) - page 2-5 Monday-Friday, 8:00 am -4 pm Domestic Violence - page 4-5 Family Law Clinic 720-772-2501 Internet Sites - page 5 100 Jefferson County Pkwy, Golden, CO 80401 *Some clinics are informational Website: only and do not provide legal advice, help completing forms, or This clinic is informational ONLY. It covers the process of divorce, legal legal representation. separation, dissolution of civil union, and APR Please contact Navigation for o Second Wednesday of each month, 12:00 pm-1:30 pm additional Domestic Violence o No reservations required legal resources as needed. o Located in Jury Assembly Office, 1st floor If you notice any changes or o Topics include: initial filings, temporary orders, separation inconsistencies with our agreements, parenting plans, maintenance/child support, custody, resources, please inform disclosure, sworn financial statements, and status conferences Navigation to help us -

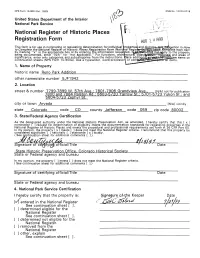

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NFS Form 10-900 (Oct. 1990) OMB No. 10024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual ;wction in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Regisfle , fete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. lfa#fl_ ply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classi 1 and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions, flace additi __ items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor! or com items. 1. Name of Property historic name Reno Park Addition__________ other names/site number 5JF1 942 2. Location street & number 7799-7899 W. 57th Ave.: 7801-7906 Grandview Ave.. N/A] not for publication 7800 and/884 :TaTston Kd.: bb'03-b/2U Yarrow St.: b/UT75723 Yukon St.; and b6U4-b/23 Zephyr St: city or town Arvada [N/A] vicinity state Colorado code CO county Jefferson code 059 zip code 80002 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [ x ] nomination f ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [ x ] meets [ ] does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Municipal Parks Parkways

MMuunniicciippaall PPaarrkkss aanndd PPaarrkkwwaayyss IN THE CCOOLLOORRAADDOO SSTTAATTEE RREEGGIISSTTEERR OF HHIISSTTOORRIICC PPRROOPPEERRTTIIEESS Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation Colorado Historical Society DIRECTORY OF MMuunniicciippaall PPaarrkkss aanndd PPaarrkkwwaayyss IN THE CCOOLLOORRAADDOO SSTTAATTEE RREEGGIISSTTEERR OOFF HHIISSTTOORRIICC PPRROOPPEERRTTIIEESS Includes Colorado properties listed in the National Register of Historic Places and the State Register of Historic Properties Updated Through December 2006 Prepared By Lisa Werdel © 2006 Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation Colorado Historical Society 1300 Broadway Denver, Colorado 80203-2137 www.coloradohistory-oahp.org The Colorado State Register of Historic Properties is a program of the Colorado Historical Society. Founded in 1879, the Colorado Historical Society brings the unique character of Colorado's past to more than a million people each year through historical museums and highway markers, exhibitions, manuscript and photograph collections, popular and scholarly publications, historical and archaeological preservation services, and educational programs for children and adults. The Society collects, preserves, and interprets the history of Colorado for present and future generations. A nonprofit agency with its own membership, the Society is also a state institution located within Colorado's Department of Higher Education The Colorado Historical Society operates twelve historic sites and museums at ten locations around the state, including