Choreographer in His Element

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Arthur Mitchell

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Arthur Mitchell Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Mitchell, Arthur, 1934-2018 Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Arthur Mitchell, Dates: October 5, 2016 Bulk Dates: 2016 Physical 9 uncompressed MOV digital video files (4:21:20). Description: Abstract: Dancer, choreographer, and artistic director Arthur Mitchell (1934 - 2018 ) was a principal dancer for the New York City Ballet for fifteen years. In 1969, he co-founded the Dance Theatre of Harlem, the first African American classical ballet company and school. Mitchell was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on October 5, 2016, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2016_034 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Dancer, choreographer and artistic director Arthur Mitchell was born on March 27, 1934 in Harlem, New York to Arthur Mitchell, Sr. and Willie Hearns Mitchell. He attended the High School of Performing Arts in Manhattan. In addition to academics, Mitchell was a member of the New Dance Group, the Choreographers Workshop, Donald McKayle and Company, and High School of Performing Arts’ Repertory Dance Company. After graduating from high school in 1952, Mitchell received scholarships to attend the Dunham School and the School of American received scholarships to attend the Dunham School and the School of American Ballet. In 1954, Mitchell danced on Broadway in House of Flowers with Geoffrey Holder, Louis Johnson, Donald McKayle, Alvin Ailey and Pearl Bailey. -

4Th MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE

th 4 MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE MÉXICO, 17 TO 24 JANUARY, 2018 SOCIAL PROGRAMME: ROYAL PEDREGAL HOTEL ACADEMIC PROGRAMME: NATIONAL AUTONOMOUS UNIVERSITY OF MEXICO Auditorio Alfonso Caso and Anexos de la Facultad de Derecho FINAL PROGRAMME (Online version linked to abstracts. Download PDF here) 1/47 All delegates please note: 1. Presentation slots may have needed to be moved by the organisers, and may appear in a different place from that of the final printed programme. Please consult the schedule located in the Conference Programme upon arrival at the Conference for your presentation time. 2. Please note that presenters have to ensure the following times for presentation to allow for adequate time for questions from the floor and smooth transition of sessions. Delegates must not stray from their allocated 20 minutes. Further, delegates are welcome to move within sessions, therefore presenters MUST limit their talk to the allocated time. Therefore, Q&A will be AFTER each talk, and NOT at the end of the three presentations. Plenary and Invited Talks – 45 min. presentation and 15 min. discussion (Q&A). 3. For panels, each panellist must stick strictly to a 10 minute time frame, before discussion with the floor commences. 4. Note that co-authors may be presenting at the conference in place of, or with the main author. For all co-authors, delegates are advised to consult the Conference Abstracts link on the Minding Animals website. Use of the term et al is provided where there is more than two authors of an abstract. 5. Moderator notes will be available at all front desks in tutorial rooms, along with Time Sheets (5, 3 and 1 minute Left). -

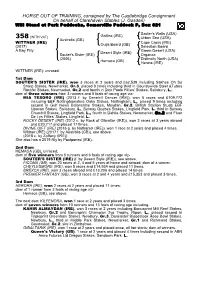

HORSE out of TRAINING, Consigned by the Castlebridge Consignment on Behalf of Clarehaven Stables (J

HORSE OUT OF TRAINING, consigned by The Castlebridge Consignment On behalf of Clarehaven Stables (J. Gosden) Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Somerville Paddock P, Box 821 Sadler's Wells (USA) Galileo (IRE) 358 (WITH VAT) Urban Sea (USA) Australia (GB) Cape Cross (IRE) WITTNER (IRE) Ouija Board (GB) (2017) Selection Board A Bay Filly Green Desert (USA) Desert Style (IRE) Souter's Sister (IRE) Organza (2006) Distinctly North (USA) Hemaca (GB) Herora (IRE) WITTNER (IRE): unraced. 1st Dam SOUTER'S SISTER (IRE), won 3 races at 2 years and £62,539 including Sakhee Oh So Sharp Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.3, placed 8 times including third in Countrywide Steel &Tubes Rockfel Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2 and fourth in Dick Poole Fillies’ Stakes, Salisbury, L.; dam of three winners from 3 runners and 5 foals of racing age viz- MIA TESORO (IRE) (2013 f. by Danehill Dancer (IRE)), won 5 races and £109,772 including EBF Nottinghamshire Oaks Stakes, Nottingham, L., placed 9 times including second in Gulf News Balanchine Stakes, Meydan, Gr.2, British Stallion Studs EBF Upavon Stakes, Salisbury, L., Betway Quebec Stakes, Lingfield Park, L. third in Betway Churchill Stakes, Lingfield Park, L., fourth in Dahlia Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2 and Fluer De Lys Fillies’ Stakes, Lingfield, L. ROCKY DESERT (IRE) (2012 c. by Rock of Gibraltar (IRE)), won 2 races at 3 years abroad and £20,717 and placed 17 times. DIVINE GIFT (IRE) (2016 g. by Nathaniel (IRE)), won 1 race at 2 years and placed 4 times. Wittner (IRE) (2017 f. by Australia (GB)), see above. -

Media Guide 2020

MEDIA GUIDE 2020 Contents Welcome 05 Minstrel Stakes (Group 2) 54 2020 Fixtures 06 Jebel Ali Racecourse & Stables Anglesey Stakes (Group 3) 56 Race Closing 2020 08 Kilboy Estate Stakes (Group 2) 58 Curragh Records 13 Sapphire Stakes (Group 2) 60 Feature Races 15 Keeneland Phoenix Stakes (Group 1) 62 TRM Equine Nutrition Gladness Stakes (Group 3) 16 Rathasker Stud Phoenix Sprint Stakes (Group 3) 64 TRM Equine Nutrition Alleged Stakes (Group 3) 18 Comer Group International Irish St Leger Trial Stakes (Group 3) 66 Coolmore Camelot Irish EBF Mooresbridge Stakes (Group 2) 20 Royal Whip Stakes (Group 3) 68 Coolmore Mastercraftsman Irish EBF Athasi Stakes (Group 3) 22 Coolmore Galileo Irish EBF Futurity Stakes (Group 2) 70 FBD Hotels and Resorts Marble Hill Stakes (Group 3) 24 A R M Holding Debutante Stakes (Group 2) 72 Tattersalls Irish 2000 Guineas (Group 1) 26 Snow Fairy Fillies' Stakes (Group 3) 74 Weatherbys Ireland Greenlands Stakes (Group 2) 28 Kilcarn Stud Flame Of Tara EBF Stakes (Group 3) 76 Lanwades Stud Stakes (Group 2) 30 Round Tower Stakes (Group 3) 78 Tattersalls Ireland Irish 1000 Guineas (Group 1) 32 Comer Group International Irish St Leger (Group 1) 80 Tattersalls Gold Cup (Group 1) 34 Goffs Vincent O’Brien National Stakes (Group 1) 82 Gallinule Stakes (Group 3) 36 Moyglare Stud Stakes (Group 1) 84 Ballyogan Stakes (Group 3) 38 Derrinstown Stud Flying Five Stakes (Group 1) 86 Dubai Duty Free Irish Derby (Group 1) 40 Moyglare ‘Jewels’ Blandford Stakes (Group 2) 88 Comer Group International Curragh Cup (Group 2) 42 Loughbrown -

Tdn Europe • Page 2 of 11 • Thetdn.Com Friday • 19 February 2021

FRIDAY, 19 FEBRUARY 2021 MNASEK MUCH THE BEST IN UAE OAKS SUMMER ROMANCE TAKES Mnasek (Empire Maker), a $15,000 purchase by Al Rashid NEXT STEP IN BALANCHINE Stables at the Fasig-Tipton Midlantic Sale last June, continued to write her fairytale story at Meydan on Thursday, posting her second win from three starts and first stakes win with a facile score in the G3 UAE Oaks. A longshot 6 3/4-length winner on debut going seven furlongs at Meydan on Dec. 17, Mnasek had to settle for second, seven lengths behind Saturday=s Saudi Derby contender Soft Whisper (Ire) (Dubawi {Ire}), after missing the break in the Listed UAE 1000 Guineas up to a mile on Jan. 28. Away much more smoothly up to 1900 metres on Thursday, Mnasek broke on top from the rail but soon dropped back to allow Jumeirah Beach (Ire) (Exceed and Excel {Aus}) to take up the running. Fourth and about three lengths off the lead rounding the first bend, jockey Pat Dobbs made a deliberate move to put the filly on the outside midway down the backstretch and she was poised ominously four-wide rounding Summer Romance | DRC/Erika Rasmussen the bend. Shooting to the lead as they straightened, Mnasek By Kelsey Riley drew clear effortlessly to crush her overmatched opposition by Summer Romance (Ire) (Kingman {GB}) was named a >TDN 6 1/2 lengths. Nayefah (Super Saver) made eye-catching Rising Star= on debut when winning a Yarmouth maiden by two headway late to be second, while Last Sunset (Ire) (Teofilo {Ire}) lengths in June of 2019, and she followed that effort up was third. -

Curriculum Vitae James R. Sandifer

Curriculum Vitae James R. Sandifer March 09, 2020 General Information University address: School of Dance College of Fine Arts Montgomery 0202 Florida State University Tallahassee, Florida 32306-2120 Phone: (850) 644-1024; Fax: (850) 644-1277 E-mail address: [email protected] Professional Preparation 1982 B.F.A., University Of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS. Major: Theater: Design and Production. Professional Experience 2019–present Associate Chair, Professor, School of Dance, Florida State University. Responsible for oversight of School of Dance productions, budgeting and calendar. 2016–2019 Director of Production, Professor, School of Dance, Florida State University. Responsible for the oversight of School of Dance productions and calendar. 2015–2016 Associate Chair, Professor, School of Dance, Florida State University. Responsible for oversight of School of Dance productions, budgeting and calendar. 2009–2015 Co-Chair, Professor, School of Dance, Florida State University. Responsible for the shared operation and direction of the School of Dance and its programs. The School's limited access degree programs have approximately ninety-five undergraduate and thirty graduate students enrolled, with a faculty of seventeen and a staff of ten. The school also services approximately 400 non-major dance students per semester. I was principally responsible for creation and supervision of budget and personnel, calendar, productions and facilities. The Maggie Allesee National Center for Choreography, the only dance research center of its kind, once directed by Jennifer Calienes and now Vita for James R. Sandifer by Carla Maxwell, is a part of the School of Dance and under the governance of the Co-Chairs. 2007–2009 Co-Chair, Associate Professor, School of Dance, Florida State University. -

Checklist for "DA 335: Dance & Society II" with Assistant Professor of Dance Jason Ohlberg the Frances Young Tang

The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College Checklist for "DA 335: Dance & Society II" with Assistant Professor of Dance Jason Ohlberg Costas Cacaroukas Kay Mazzo and Peter Martins in "Violin Concerto", n.d. photograph 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.86 Costas Cacaroukas Suzanne Farrell on Peter Martins photograph 10 x 8 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.212 Steven Caras Kay Mazzo and Peter Martins in "Violin Concerto", n.d. photograph 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.81 Fred Fehl Melissa Hayden and Roland Vazquez in "Midsummer's Night Dream", n.d. gelatin silver print 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.125 Carolyn George Suzanne Farrell, n.d. photograph 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.76 Carolyn George Allegra Kent and Bart Cook in "Episodes", n.d. photograph 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.170 George Platt Lynes André Eglevsky, Diana Adams, Maria Tallchief, Tanaquil LeClercq in "Apollon Musagète", 1951 photograph 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.95 Martha Swope Suzanne Farrell and Arthur Mitchell in "Metastaseis and Pithoprakta", n. d. photograph 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.70 Martha Swope Four pairs of dancers, n.d. photograph 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.97 Martha Swope Diana Adams with Arthur Mitchell in "Agon", n.d. -

138904 09 Juvenilefilliesturf.Pdf

breeders’ cup JUVENILE FILLIES TURF BREEDERs’ Cup JUVENILE FILLIES TURF (GR. I) 6th Running Santa Anita Park $1,000,000 Guaranteed FOR FILLIES, TWO-YEARS-OLD ONE MILE ON THE TURF Weight, 122 lbs. Guaranteed $1 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Friday, November 1, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Al Thakhira (GB) Sheikh Joaan Bin Hamad Al Thani Marco Botti B.f.2 Dubawi (IRE) - Dahama (GB) by Green Desert - Bred in Great Britain by Qatar Bloodstock Ltd Chriselliam (IRE) Willie Carson, Miss E. Asprey & Christopher Wright Charles Hills B.f.2 Iffraaj (GB) - Danielli (IRE) by Danehill - Bred in Ireland by Ballylinch Stud Clenor (IRE) Great Friends Stable, Robert Cseplo & Steven Keh Doug O'Neill B.f.2 Oratorio (IRE) - Chantarella (IRE) by Royal Academy - Bred in Ireland by Mrs Lucy Stack Colonel Joan Kathy Harty & Mark DeDomenico, LLC Eoin G. -

The Balanchine Trust: Dancing Through the Steps of Two-Part Licensing

Volume 6 Issue 2 Article 2 1999 The Balanchine Trust: Dancing through the Steps of Two-Part Licensing Cheryl Swack Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Cheryl Swack, The Balanchine Trust: Dancing through the Steps of Two-Part Licensing, 6 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 265 (1999). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol6/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Swack: The Balanchine Trust: Dancing through the Steps of Two-Part Licen THE BALANCHINE TRUST: DANCING THROUGH THE STEPS OF TWO-PART LICENSING CHERYL SWACK* I. INTRODUCTION A. George Balanchine George Balanchine,1 "one of the century's certifiable ge- * Member of the Florida Bar; J.D., University of Miami School of Law; B. A., Sarah Lawrence College. This article is dedicated to the memory of my mother, Allegra Swack. 1. Born in 1904 in St. Petersburg, Russia of Georgian parents, Georgi Melto- novich Balanchivadze entered the Imperial Theater School at the Maryinsky Thea- tre in 1914. See ROBERT TRAcy & SHARON DELONG, BALANci-NE's BALLERINAS: CONVERSATIONS WITH THE MUSES 14 (Linden Press 1983) [hereinafter TRAcY & DELONG]. His dance training took place during the war years of the Russian Revolution. -

Lorena Baricalla

LORENA BARICALLA PRIMA BALLERINA – SINGER – ACTRESS MASTER OF CEREMONIES CHOREOGRAPHER – WRITER – PRODUCER Internationally recognized Lorena Baricalla is a multi-talented artist. She is a Prima ballerina, singer and actress as well as choreographer, writer and producer. Moreover sHe is also Master of Ceremonies, Fashion Ambassadress/Endorser and Ambassadress for international projects. She Has built Her career in more tHan 35 countries around tHe world, in theatre and television. Family Story: Born into a family of Monaco since more tHan 5 generations witH Italian, French, Czech and German origins, Lorena has always lived in Monte-Carlo. Her parents were married in Monte Carlo’s Saint CHarles CHurcH. Her motHer, Joelle Heidl, a FrencHwoman from Monaco, Had trained as a ballerina and ballet teacher with Marika Besobrasova: later Lorena Baricalla would also become Her pupil. Lorena’s fatHer was a well-known Italian surgeon, Renzo Baricalla. Purely by cHance sHe was born prematurely on 10tH May in Savona, Italy, while Her motHer was visiting Her in-laws. Her fatHer missed Her birtH as He was on tHe Monaco Formula 1 Grand PriX track, where tHe race was taking place tHat day. Lorena grew up at tHe Hotel de la Poste in Monaco. For over 50 years tHe Hotel Had belonged to her maternal grandparents, Ernst Heidl and Marie-Louise Vigna. It was a family run Hotel: its restaurant, run by Her grandfather, a CzecH-German cHef wHo Had qualified at tHe Prague Hotel ScHool, was frequented by known artists and sportsmen as well as local identities. Previously Lorena’s great-grandparents, Albina Chiesa and Luigi Vigna that were also married in Monaco, Had kept Monaco’s Hotel Restaurant des Voyageurs. -

East by Northeast the Kingdom of the Shades (From Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Music by Ludwig Minkus Staged by Glenda Lucena

2013/2014 La Bayadère Act II | Airs | Donizetti Variations Photo by Paul B. Goode, courtesy of the Paul Taylor Dance Company East by Spring Ballet Northeast Seven Hundred Fourth Program of the 2013-14 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents Spring Ballet: East by Northeast The Kingdom of the Shades (from Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Music by Ludwig Minkus Staged by Glenda Lucena Donizetti Variations Choreography by George Balanchine Music by Gaetano Donizetti Staged by Sandra Jennings Airs Choreography by Paul Taylor Music by George Frideric Handel Staged by Constance Dinapoli Michael Vernon, Artistic Director, IU Ballet Theater Stuart Chafetz, Conductor Patrick Mero, Lighting Design _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, March Twenty-Eighth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, March Twenty-Ninth, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, March Twenty-Ninth, Eight O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Kingdom of the Shades (from Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Staged by Glenda Lucena Music by Ludwig Minkus Orchestration by John Lanchbery* Lighting Re-created by Patrick Mero Glenda Lucena, Ballet Mistress Violette Verdy, Principals Coach Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Phillip Broomhead, Guest Coach Premiere: February 4, 1877 | Imperial Ballet, Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre, St. Petersburg Grand Pas de Deux Nikiya, a temple dancer . Alexandra Hartnett Solor, a warrior. Matthew Rusk Pas de Trois (3/28 and 3/29 mat.) First Solo. Katie Zimmerman Second Solo . Laura Whitby Third -

Dancing Into the Chthulucene: Sensuous Ecological Activism In

Dancing into the Chthulucene: Sensuous Ecological Activism in the 21st Century Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kelly Perl Klein Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Dr. Harmony Bench, Advisor Dr. Ann Cooper Albright Dr. Hannah Kosstrin Dr. Mytheli Sreenivas Copyrighted by Kelly Perl Klein 2019 2 Abstract This dissertation centers sensuous movement-based performance and practice as particularly powerful modes of activism toward sustainability and multi-species justice in the early decades of the 21st century. Proposing a model of “sensuous ecological activism,” the author elucidates the sensual components of feminist philosopher and biologist Donna Haraway’s (2016) concept of the Chthulucene, articulating how sensuous movement performance and practice interpellate Chthonic subjectivities. The dissertation explores the possibilities and limits of performances of vulnerability, experiences of interconnection, practices of sensitization, and embodied practices of radical inclusion as forms of activism in the context of contemporary neoliberal capitalism and competitive individualism. Two theatrical dance works and two communities of practice from India and the US are considered in relationship to neoliberal shifts in global economic policy that began in the late 1970s. The author analyzes the dance work The Dammed (2013) by the Darpana Academy for Performing Arts in Ahmedabad,