140 the SOCIO-SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT of JAFFA–TEL AVIV: the Emergence and Fade-Away of Ethnic Divisions and Distinctions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Israel Trip ITINERARY

ITINERARY The Cohen Camps’ Women’s Trip to Israel Led by Adina Cohen April 10-22, 2018 Tuesday April 10 DEPARTURE Departure from Boston (own arrangements) Wednesday April 11 BRUCHIM HABA’AIM-WELCOME TO ISRAEL! . Rendezvous at Ben Gurion airport at 14:10 (or at hotel in Tel Aviv) . Opening Program at the Port of Jaffa, where pilgrims and olim entered the Holy Land for centuries. Welcome Dinner at Café Yafo . Check-in at hotel Overnight: Carlton, Tel Aviv Thursday April 12 A LIGHT UNTO THE NATIONS . Torah Yoga Session . Visit Save a Child’s Heart-a project of Wolfston Hospital, in which Israeli pediatric surgeons provide pro-bono cardiac surery for children from all over Africa and the Middle East. “Shuk Bites” lunch in the Old Jaffa Flea Market . Visit “The Women’s Courtyard” – a designer outlet empowering Arab and Jewish local women . Israeli Folk Dancing interactive program- Follow the beat of Israeli women throughout history and culture and experience Israel’s transformation through dance. Enjoy dinner at the “Liliot” Restaurant, which employs youth at risk. Overnight: Carlton, Tel Aviv Friday April 13 COSMOPOLITAN TEL AVIV . Interactive movement & drum circle workshop with Batya . “Shuk & Cook” program with lunch at the Carmel Market . Stroll through the Nahalat Binyamin weekly arts & crafts fair . Time at leisure to prepare for Shabbat . Candle lighting Cohen Camps Women’s Trip to Israel 2018 Revised 22 Aug 17 Page 1 of 4 . Join Israelis for a unique, musical “Kabbalat Shabbat” with Bet Tefilah Hayisraeli, a liberal, independent, and egalitarian community in Tel Aviv, which is committed to Jewish spirit, culture, and social action. -

Frauenleben in Magenza

www.mainz.de/frauenbuero Frauenleben in Magenza Porträts jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen aus dem Mainzer Frauenkalender seit 1991 und Texte zur Frauengeschichte im jüdischen Mainz Frauenleben in Magenza Frauenleben in Magenza Die Porträts jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen aus dem Mainzer Frauenkalender und Texte zur Frauengeschichte im jüdischen Mainz 3 Frauenleben in Magenza Impressum Herausgeberin: Frauenbüro Landeshauptstadt Mainz Stadthaus Große Bleiche Große Bleiche 46/Löwenhofstraße 1 55116 Mainz Tel. 06131 12-2175 Fax 06131 12-2707 [email protected] www.mainz.de/frauenbuero Konzept, Redaktion, Gestaltung: Eva Weickart, Frauenbüro Namenskürzel der AutorInnen: Reinhard Frenzel (RF) Martina Trojanowski (MT) Eva Weickart (EW) Mechthild Czarnowski (MC) Bildrechte wie angegeben bei den Abbildungen Titelbild: Schülerinnen der Bondi-Schule. Privatbesitz C. Lebrecht Druck: Hausdruckerei 5. überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage Mainz 2021 4 Frauenleben in Magenza Vorwort des Oberbürgermeisters Die Geschichte jüdischen Lebens und Gemein- Erstmals erschienen ist »Frauenleben in Magen- delebens in Mainz reicht weit zurück in das 10. za« aus Anlass der Eröffnung der Neuen Syna- Jahrhundert, sie ist damit auch die Geschichte goge im Jahr 2010. Weitere Auflagen erschienen der jüdischen Frauen dieser Stadt. 2014 und 2015. Doch in vielen historischen Betrachtungen von Magenza, dem jüdischen Mainz, ist nur selten Die Veröffentlichung basiert auf den Porträts die Rede vom Leben und Schicksal jüdischer jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen und auf den Frauen und Mädchen. Texten zu Einrichtungen jüdischer Frauen und Dabei haben sie ebenso wie die Männer zu al- Mädchen, die seit 1991 im Kalender »Blick auf len Zeiten in der Stadt gelebt, sie haben gelernt, Mainzer Frauengeschichte« des Frauenbüros gearbeitet und den Alltag gemeistert. -

Tel Aviv Elite Guide to Tel Aviv

DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES TEL AVIV ELITE GUIDE TO TEL AVIV HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV 3 ONLY ELITE 4 Elite Traveler has selected an exclusive VIP experience EXPERT RECOMMENDATIONS 5 We asked top local experts to share their personal recommendations ENJOY ELEGANT SEA-FACING LUXURY AT THE CARLTON for the perfect day in Tel Aviv WHERE TO ➤ STAY 7 ➤ DINE 13 ➤ BE PAMPERED 16 RELAX IN STYLE AT THE BEACH WHAT TO DO ➤ DURING THE DAY 17 ➤ DURING THE NIGHT 19 ➤ FEATURED EVENTS 21 ➤ SHOPPING 22 TASTE SUMPTUOUS GOURMET FLAVORS AT YOEZER WINE BAR NEED TO KNOW ➤ MARINAS 25 ➤ PRIVATE JET TERMINALS 26 ➤ EXCLUSIVE TRANSPORT 27 ➤ USEFUL INFORMATION 28 DISCOVER CUTTING EDGE DESIGNER STYLE AT RONEN ChEN (C) ShAI NEIBURG DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES ELITE DESTINATION GUIDE | TEL AVIV www.elitetraveler.com 2 HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV Don’t miss out on the wealth of attractions, adventures and experiences on offer in ‘The Miami of the Middle East’ el Aviv is arguably the most unique ‘Habuah’ (‘The Bubble’), for its carefree Central Tel Aviv’s striking early 20th T city in Israel and one that fascinates, and fun-loving atmosphere, in which century Bauhaus architecture, dubbed bewilders and mesmerizes visitors. the difficult politics of the region rarely ‘the White City’, is not instantly Built a mere century ago on inhospitable intrudes and art, fashion, nightlife and attractive, but has made the city a World sand dunes, the city has risen to become beach fun prevail. This relaxed, open vibe Heritage Site, and its golden beaches, a thriving economic hub, and a center has seen Tel Aviv named ‘the gay capital lapped by the clear azure Mediterranean, of scientific, technological and artistic of the Middle East’ by Out Magazine, are beautiful places for beautiful people. -

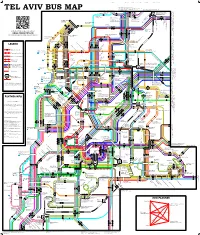

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

May 1999 Vol 25 No

m Vff TELFED MAY 1999 VOL 25 NO. 2 A SOUTH AFRICAN ZIONIST FEDERATION (ISRAEL) PUBLICATION THE SOUTH AFRICAN WAY iy A MODEL FOR OTHER NATIONS? HEALTH: Brcaklhroiighs in Brcasi Care BOOK REVIEW Viviennc Silver's "Docitnienling ihe Dream" NUPTIALS, route '94 ARRIVALS.... AND MORE [under reconciliation! 46 SOKOLOV (2nd Floor) RAMAT-HASHARON Tel. 03-5488111 Home 09-7446967 F a x 0 3 - 5 4 0 0 0 7 7 Dear Friends, By the time you read this note we will hopefully have a new Government and one will be able to think about more mundane matters such as overseas trips and other such pleasures of daily life. This Pesach really lent itself to a good overseas trip with two long weekends and the well-placed Chagim. On looking through "Places not yet Visited," Italy stood out. So near — only a 3-hour flight - and with all the components for a great holiday. I called my friendly travel agent and in no time had arranged a lovely apartment for four nights in the heart of Tuscany — Rada in Chianti - you've probably never heard of it (neither had I!!!). We landed in a great setting with beautiful views, lovely walks, quaint towns, and of course, wonderful restaurants of all types and descriptions. It's really a great way to spend a vacation, renting a villa in Tuscany or a room in a villa. In the main, they are not serviced, no food, but reasonably priced and a great base for exploring the whole area. It's only 2.5 hours drive from Rome or Milan and 30 minutes from Florence, where we spent the fifth night. -

—PALESTINE and the MIDDLE EAST-N

PALESTINE AND MIDDLE EAST 409 —PALESTINE AND THE MIDDLE EAST-n By H. Lowenberg— PALESTINE THE YEAR BEGINNINO June, 1947, and ending May, 1948 was among the most crucial and critical periods in Palestine's modern history. The United Nations' historic partition decision of November 29, 1947, divided the year into two halves, each of different importance for the Yishuv and indeed for all Jewry: the uneasy peace before, and the commu- nal war after the UN decision; the struggle to find a solution to the Palestine problem before, and to prepare for and defend the Jewish state after that fateful day. Outside Palestine, in the Middle East as a whole, the UN partition decision and the Arab rebellion against it, left a mark scarcely less profound than in Palestine itself. UNSCOP On May 13, 1947, the special session of the General As- sembly of the United Nations created the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) with instructions to "prepare and report to the General Assembly and submit such proposals as it may consider appropriate for the solution of the problem of Palestine . not later than September ,1, 1947." In Palestine, the Arabs followed news of UNSCOP with apparent indifference. They adopted an attitude of hostil- ity towards the Committee, and greeted it with a two-day protest strike starting on June 15, 1947. Thereafter, they 410 AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK took no further notice of the Committee, the Arab press even obeying the Mufti's orders not to print any mention of UNSCOP. This worried the Committee, as boycott by one side to the dispute might mean a serious gap in its fact finding. -

The Strategic Plan for Tel Aviv-Yafo

THE STRATEGIC PLAN FOR TEL AVIV-YAFO The City Vision / December 2017 THE STRATEGIC PLAN FOR TEL AVIV-YAFO The City Vision / December 2017 A Message from the Mayor This document presents the today. It has gone from being a 'disregarded city' to a 'highly updated Strategic Plan for Tel regarded city' with the largest population it ever had, and from Aviv-Yafo and sets forth the a 'waning city' to a 'booming city' that is a recognized leader and vision for the city's future in the pioneer in many fields in Israel and across the globe. coming years. Because the world is constantly changing, the city – and Approximately two decades especially a 'nonstop city' like Tel Aviv-Yafo – must remain up have elapsed since we initiated to date and not be a prisoner of the past when planning its the preparation of a Strategic future. For that reason, about two years ago we decided the Plan for the city. As part time had come to revise the Strategic Plan documents and of the change we sought to achieve at the time in how the adapt our vision to the changing reality. That way we would be Municipality was managed - and in the absence of a long-term able to address the significant changes that have occurred in plan or zoning plan that outlined our urban development – we all spheres of life since drafting the previous plan and tackle the attached considerable importance to a Strategic Plan which opportunities and challenges that the future holds. would serve as an agreed-upon vision and compass to guide As with the Strategic Plan, the updating process was also our daily operations. -

The Limits of Separation: Jaffa and Tel Aviv Before 1948—The Underground Story

– Karlinsky The Limits of Separation THE LIMITS OF SEPARATION: JAFFA AND TEL AVIV — BEFORE 1948 THE UNDERGROUND STORY In: Maoz A zaryahu and S. Ilan Troen (eds.), Tel-Aviv at 100: Myths, Memories and Realities (Indiana University Press, in print) Nahum Karlinsky “ Polarized cities are not simply mirrors of larger nationalistic ethnic conflicts, but instead can be catalysts through which conflict is exacerbated ” or ameliorated. Scott A. Bollens, On Narrow Ground: Urban Policy and Ethnic Conflict in Jerusalem and Belfast (Albany, NY, 2000), p. 326. Abstract — This article describes the development of the underground infrastructure chiefly the — water and sewerage systems of Tel Aviv and Jaffa from the time of the establishment of Tel Aviv (1909) to 1948. It examines the realization of the European-informed vision of ’ Tel Aviv s founders in regard to these underground constructs in a basically non-European context. It adds another building block, however small and partial, to the growing number of studies that aspire to reconstruct that scantily researched area of relations between Jaffa and Tel Aviv before 1948. Finally, it revisits pre-1948 ethnic and national relations ’ between the country s Jewish collective and its Palestinian Arab population through the prism of the introduction of a seemingly neutral technology into a dense urban setting, and the role played by a third party (here, mainly, the British authorities) in shaping these relations. Models of Urban Relations in Pre-1948 Palestine The urban history of pre-1948 Palestine has gained welcome momentum in recent years. Traditionally, mainstream Zionist and Palestinian historiographies concentrated mainly on the rural sector, which for both national communities symbolized a mythical attachment to “ ” the land. -

Tel Aviv University the Buchmann Faculty of Law

TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY THE BUCHMANN FACULTY OF LAW HANDBOOK FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS 2014-2015 THE OFFICE OF STUDENT EXCHANGE PROGRAM 1 Handbook for International Students Tel Aviv University, the Buchmann Faculty of Law 2014-2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 4 I. The Buchmann Faculty of Law 4 II. About the student exchange program 4 III. Exchange Program Contact persons 5 IV. Application 5 V. Academic Calendar 6 2. ACADEMIC INFORMATION 7 I. Course registration and Value of Credits 7 II. Exams 8 III. Transcripts 9 IV. Student Identification Cards and TAU Email Account 9 V. Hebrew Language Studies 9 VI. Orientation Day 9 3. GENERAL INFORMATION 10 I. Before You Arrive 10 1. About Israel 10 2. Currency and Banks 10 3. Post Office 11 4. Cellular Phones 11 5. Cable TV 12 6. Electric Appliances 12 7. Health Care & Insurance 12 8. Visa Information 12 II. Living in Tel- Aviv 13 1. Arriving in Tel- Aviv 13 2. Housing 13 3. Living Expenses 15 4. Transportation 15 2 III. What to Do in Tel-Aviv 17 1. Culture & Entertainment 17 2. Tel Aviv Nightlife 18 3. Restaurants and Cafes 20 4. Religious Centers 23 5. Sports and Recreation 24 6. Shopping 26 7. Tourism 26 8. Emergency Phone Numbers 27 9. Map of Tel- Aviv 27 4. UNIVERSITY INFORMATION 28 1. Important Phone Numbers 28 2. University Book Store 29 3. Campus First Aid 29 4. Campus Dental First Aid 29 5. Law Library 29 6. University Map 29 7. Academic Calendar 30 3 INTRODUCTION The Buchmann Faculty of Law Located at the heart of Tel Aviv, TAU Law Faculty is Israel’s premier law school. -

"History Takes Place — Dynamics of Urban Change"

Summer School in Tel Aviv–Jaffa "History Takes Place — Dynamics of Urban Change" 23-27 September 2019 REPORT hosted by Impressum Project Director Dr. Anna Hofmann, Director, Head of Research and Scholarship, ZEIT-Stiftung Ebelin und Gerd Bucerius, Hamburg [email protected] Project Manager Marcella Christiani, M.A., Project Manager Research and Scholarship, ZEIT-Stiftung Ebelin und Gerd Bucerius, Hamburg [email protected] Guy Rak, PhD, Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies, [email protected] Liebling Haus – The White City Center (WCC) Shira Levy Benyemini, Director [email protected] Sharon Golan Yaron, Program Director and Conservation Architect [email protected] Orit Rozental, Architect, Conservation Department, Tel Aviv-Jaffo Municipality Yarden Diskin, Research Assistant; MA Urban Planning (Technion Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa) [email protected] Report: Dr. Anna Hofmann, Marcella Christiani Photos: © Yael Schmidt Photography, Tel Aviv: page 1 until 5, 6 below, 7, 10, 11, 12 above, 14, 15, 16 below and 17 others: Dr. Anna Hofmann and Marcella Christiani Photo Cover: Barak Brinker From 23 to 27 September 2019, the ZEIT-Stiftung Ebelin und Gerd Bucerius, in collaboration with the Gerda Henkel Foundation, organized the ninth edition of the Summer School “History Takes Place – Dynamics of Urban Change” in Tel Aviv-Jaffa (Israel), focusing on its Bauhaus heritage. Under the appellation of 'White City of Tel Aviv: The Modern Movement', it has been part of the UNESCO proclaimed World Heritage Site since 2003. Fourteen young historians, scholars in cultural studies and social sciences, artists, city planners and architects discovered the city, studying the connections between historical events and spatial development. -

Post-Traumatic Urbanism: Repressing Manshiya and Wadi Salib T ⁎ Gabriel Schwake

Cities 75 (2018) 50–58 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Cities journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cities Post-traumatic urbanism: Repressing Manshiya and Wadi Salib T ⁎ Gabriel Schwake David Azrieli School of Architecture, Tel Aviv University, Israel TU Delft, Faculty of Architecture & The Built Environment, The Netherlands ABSTRACT Trauma is defined as a wound or an injury caused by an act of violence on one's body, or as a severe anxiety caused by an unpleasant experience. The victims of traumatic events may develop psychological stress disorder, which is manifested in several symptoms: post-traumatic stress disorder. The 1948 Arab-Israeli had caused both physical and psychological trauma. The symptoms of this trauma are still visible today in various Israeli cities. As a result of the war, Israeli cities had annexed formerly owned Palestinian villages and neighborhoods. Along the years, these vacated Palestinian houses were settled by Jewish immigrants, turned to slums and became the target of several urban renewal projects. These renewal projects mainly asked to erase all traces of the neigh- borhood's Arab past, and to introduce a new urban order. This research focuses on Al Manshiya in Tel Aviv-Jaffa and Wadi Salib in Haifa, two former Palestinian neighborhoods, which were vacated from their original in- habitants. This research surveys the re-planning process of both neighborhoods, its implementation and its current status. Asking whether one can depict symptoms of post-trauma in the urban scheme and in the buildings' architecture. Al Manshiya was torn down completely in the 1970's, in order to make place for Tel Aviv's new central business district. -

Israel a History

Index Compiled by the author Aaron: objects, 294 near, 45; an accidental death near, Aaronsohn family: spies, 33 209; a villager from, killed by a suicide Aaronsohn, Aaron: 33-4, 37 bomb, 614 Aaronsohn, Sarah: 33 Abu Jihad: assassinated, 528 Abadiah (Gulf of Suez): and the Abu Nidal: heads a 'Liberation October War, 458 Movement', 503 Abandoned Areas Ordinance (948): Abu Rudeis (Sinai): bombed, 441; 256 evacuated by Israel, 468 Abasan (Arab village): attacked, 244 Abu Zaid, Raid: killed, 632 Abbas, Doa: killed by a Hizballah Academy of the Hebrew Language: rocket, 641 established, 299-300 Abbas Mahmoud: becomes Palestinian Accra (Ghana): 332 Prime Minister (2003), 627; launches Acre: 3,80, 126, 172, 199, 205, 266, 344, Road Map, 628; succeeds Arafat 345; rocket deaths in (2006), 641 (2004), 630; meets Sharon, 632; Acre Prison: executions in, 143, 148 challenges Hamas, 638, 639; outlaws Adam Institute: 604 Hamas armed Executive Force, 644; Adamit: founded, 331-2 dissolves Hamas-led government, 647; Adan, Major-General Avraham: and the meets repeatedly with Olmert, 647, October War, 437 648,649,653; at Annapolis, 654; to Adar, Zvi: teaches, 91 continue to meet Olmert, 655 Adas, Shafiq: hanged, 225 Abdul Hamid, Sultan (of Turkey): Herzl Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Jewish contacts, 10; his sovereignty to receive emigrants gather in, 537 'absolute respect', 17; Herzl appeals Aden: 154, 260 to, 20 Adenauer, Konrad: and reparations from Abdul Huda, Tawfiq: negotiates, 253 Abdullah, Emir: 52,87, 149-50, 172, Germany, 279-80, 283-4; and German 178-80,230,