Spatio-Syntactical Analysis and Historical Spatial Potentials: the Case of Jaffa–Tel Aviv This Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’S First Decades

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’s First Decades Rotem Erez June 7th, 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Stefan Kipfer A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Student Signature: _____________________ Supervisor Signature:_____________________ Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................9 Chapter 1: A Comparative Study of the Early Years of Colonial Casablanca and Tel-Aviv ..................... 19 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 19 Historical Background ............................................................................................................................ -

Rates, Indications, and Speech Perception Outcomes of Revision Cochlear Implantations

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Rates, Indications, and Speech Perception Outcomes of Revision Cochlear Implantations Doron Sagiv 1,2,*,†,‡, Yifat Yaar-Soffer 3,4,‡, Ziva Yakir 3, Yael Henkin 3,4 and Yisgav Shapira 1,2 1 Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer 5262100, Israel; [email protected] 2 Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv City 6997801, Israel 3 Hearing, Speech, and Language Center, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer 5262100, Israel; [email protected] (Y.Y.-S.); [email protected] (Z.Y.); [email protected] (Y.H.) 4 Department of Communication Disorders, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv City 6997801, Israel * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +972-35-302-242; Fax: +972-35-305-387 † Present address: Department of Oolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, University of California Davis, Sacramento, CA 95817, USA. ‡ Sagiv and Yaar-Soffer contributed equally to this study and should be considered joint first author. Abstract: Revision cochlear implant (RCI) is a growing burden on cochlear implant programs. While reports on RCI rate are frequent, outcome measures are limited. The objectives of the current study were to: (1) evaluate RCI rate, (2) classify indications, (3) delineate the pre-RCI clinical course, and (4) measure surgical and speech perception outcomes, in a large cohort of patients implanted in a tertiary referral center between 1989–2018. Retrospective data review was performed and included patient demographics, medical records, and audiologic outcomes. Results indicated that RCI rate Citation: Sagiv, D.; Yaar-Soffer, Y.; was 11.7% (172/1465), with a trend of increased RCI load over the years. -

Landscape and Urban Planning Xxx (2016) Xxx–Xxx

G Model LAND-2947; No. of Pages 11 ARTICLE IN PRESS Landscape and Urban Planning xxx (2016) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Landscape and Urban Planning j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/landurbplan Thinking organic, acting civic: The paradox of planning for Cities in Evolution a,∗ b Michael Batty , Stephen Marshall a Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (CASA), UCL, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK b Bartlett School of Planning, UCL, Central House, 14 Upper Woburn Place, London WC1H 0NN, UK h i g h l i g h t s • Patrick Geddes introduced the theory of evolution to city planning over 100 years ago. • His evolutionary theory departed from Darwin in linking collaboration to competition. • He wrestled with the tension between bottom-up and top-down action. • He never produced his magnum opus due the inherent contradictions in his philosophy. • His approach resonates with contemporary approaches to cities as complex systems. a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Patrick Geddes articulated the growth and design of cities in the early years of the town planning move- Received 18 July 2015 ment in Britain using biological principles of which Darwin’s (1859) theory of evolution was central. His Received in revised form 20 April 2016 ideas about social evolution, the design of local communities, and his repeated calls for comprehensive Accepted 4 June 2016 understanding through regional survey and plan laid the groundwork for much practical planning in the Available online xxx mid 20th century, both with respect to an embryonic theory of cities and the practice of planning. -

Women's Israel Trip ITINERARY

ITINERARY The Cohen Camps’ Women’s Trip to Israel Led by Adina Cohen April 10-22, 2018 Tuesday April 10 DEPARTURE Departure from Boston (own arrangements) Wednesday April 11 BRUCHIM HABA’AIM-WELCOME TO ISRAEL! . Rendezvous at Ben Gurion airport at 14:10 (or at hotel in Tel Aviv) . Opening Program at the Port of Jaffa, where pilgrims and olim entered the Holy Land for centuries. Welcome Dinner at Café Yafo . Check-in at hotel Overnight: Carlton, Tel Aviv Thursday April 12 A LIGHT UNTO THE NATIONS . Torah Yoga Session . Visit Save a Child’s Heart-a project of Wolfston Hospital, in which Israeli pediatric surgeons provide pro-bono cardiac surery for children from all over Africa and the Middle East. “Shuk Bites” lunch in the Old Jaffa Flea Market . Visit “The Women’s Courtyard” – a designer outlet empowering Arab and Jewish local women . Israeli Folk Dancing interactive program- Follow the beat of Israeli women throughout history and culture and experience Israel’s transformation through dance. Enjoy dinner at the “Liliot” Restaurant, which employs youth at risk. Overnight: Carlton, Tel Aviv Friday April 13 COSMOPOLITAN TEL AVIV . Interactive movement & drum circle workshop with Batya . “Shuk & Cook” program with lunch at the Carmel Market . Stroll through the Nahalat Binyamin weekly arts & crafts fair . Time at leisure to prepare for Shabbat . Candle lighting Cohen Camps Women’s Trip to Israel 2018 Revised 22 Aug 17 Page 1 of 4 . Join Israelis for a unique, musical “Kabbalat Shabbat” with Bet Tefilah Hayisraeli, a liberal, independent, and egalitarian community in Tel Aviv, which is committed to Jewish spirit, culture, and social action. -

Frauenleben in Magenza

www.mainz.de/frauenbuero Frauenleben in Magenza Porträts jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen aus dem Mainzer Frauenkalender seit 1991 und Texte zur Frauengeschichte im jüdischen Mainz Frauenleben in Magenza Frauenleben in Magenza Die Porträts jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen aus dem Mainzer Frauenkalender und Texte zur Frauengeschichte im jüdischen Mainz 3 Frauenleben in Magenza Impressum Herausgeberin: Frauenbüro Landeshauptstadt Mainz Stadthaus Große Bleiche Große Bleiche 46/Löwenhofstraße 1 55116 Mainz Tel. 06131 12-2175 Fax 06131 12-2707 [email protected] www.mainz.de/frauenbuero Konzept, Redaktion, Gestaltung: Eva Weickart, Frauenbüro Namenskürzel der AutorInnen: Reinhard Frenzel (RF) Martina Trojanowski (MT) Eva Weickart (EW) Mechthild Czarnowski (MC) Bildrechte wie angegeben bei den Abbildungen Titelbild: Schülerinnen der Bondi-Schule. Privatbesitz C. Lebrecht Druck: Hausdruckerei 5. überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage Mainz 2021 4 Frauenleben in Magenza Vorwort des Oberbürgermeisters Die Geschichte jüdischen Lebens und Gemein- Erstmals erschienen ist »Frauenleben in Magen- delebens in Mainz reicht weit zurück in das 10. za« aus Anlass der Eröffnung der Neuen Syna- Jahrhundert, sie ist damit auch die Geschichte goge im Jahr 2010. Weitere Auflagen erschienen der jüdischen Frauen dieser Stadt. 2014 und 2015. Doch in vielen historischen Betrachtungen von Magenza, dem jüdischen Mainz, ist nur selten Die Veröffentlichung basiert auf den Porträts die Rede vom Leben und Schicksal jüdischer jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen und auf den Frauen und Mädchen. Texten zu Einrichtungen jüdischer Frauen und Dabei haben sie ebenso wie die Männer zu al- Mädchen, die seit 1991 im Kalender »Blick auf len Zeiten in der Stadt gelebt, sie haben gelernt, Mainzer Frauengeschichte« des Frauenbüros gearbeitet und den Alltag gemeistert. -

Zefat, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century C.E. Epitaphs from the Jewish Cemetery

1 In loving memory of my mother, Batsheva Friedman Stepansky, whose forefathers arrived in Zefat and Tiberias 200 years ago and are buried in their ancient cemeteries Zefat, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century C.E. Epitaphs from the Jewish Cemetery Yosef Stepansky, Zefat Introduction In recent years a large concentration of gravestones bearing Hebrew epitaphs from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries C.E. has been exposed in the ancient cemetery of Zefat, among them the gravestones of prominent Rabbis, Torah Academy and community leaders, well-known women (such as Rachel Ha-Ashkenazit Iberlin and Donia Reyna, the sister of Rabbi Chaim Vital), the disciples of Rabbi Isaac Luria ("Ha-ARI"), as well as several until-now unknown personalities. Some of the gravestones are of famous Rabbis and personalities whose bones were brought to Israel from abroad, several of which belong to the well-known Nassi and Benvenisti families, possibly relatives of Dona Gracia. To date (2018) some fifty gravestones (some only partially preserved) have been exposed, and that is so far the largest group of ancient Hebrew epitaphs that may be observed insitu at one site in Israel. Stylistically similar epitaphs can be found in the Jewish cemeteries in Istanbul (Kushta) and Salonika, the two largest and most important Jewish centers in the Ottoman Empire during that time. Fig. 1: The ancient cemetery in Zefat, general view, facing north; the bottom of the picture is the southern, most ancient part of the cemetery. 2 Since 2010 the southernmost part of the old cemetery of Zefat (Fig. 1; map ref. 24615/76365), seemingly the most ancient part of the cemetery, has been scrutinized in order to document and organize the information inscribed on the oldest of the gravestones found in this area, in wake of and parallel with cleaning-up and preservation work conducted in this area under the auspices of the Zefat religious council. -

Tel Aviv Elite Guide to Tel Aviv

DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES TEL AVIV ELITE GUIDE TO TEL AVIV HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV 3 ONLY ELITE 4 Elite Traveler has selected an exclusive VIP experience EXPERT RECOMMENDATIONS 5 We asked top local experts to share their personal recommendations ENJOY ELEGANT SEA-FACING LUXURY AT THE CARLTON for the perfect day in Tel Aviv WHERE TO ➤ STAY 7 ➤ DINE 13 ➤ BE PAMPERED 16 RELAX IN STYLE AT THE BEACH WHAT TO DO ➤ DURING THE DAY 17 ➤ DURING THE NIGHT 19 ➤ FEATURED EVENTS 21 ➤ SHOPPING 22 TASTE SUMPTUOUS GOURMET FLAVORS AT YOEZER WINE BAR NEED TO KNOW ➤ MARINAS 25 ➤ PRIVATE JET TERMINALS 26 ➤ EXCLUSIVE TRANSPORT 27 ➤ USEFUL INFORMATION 28 DISCOVER CUTTING EDGE DESIGNER STYLE AT RONEN ChEN (C) ShAI NEIBURG DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES ELITE DESTINATION GUIDE | TEL AVIV www.elitetraveler.com 2 HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV Don’t miss out on the wealth of attractions, adventures and experiences on offer in ‘The Miami of the Middle East’ el Aviv is arguably the most unique ‘Habuah’ (‘The Bubble’), for its carefree Central Tel Aviv’s striking early 20th T city in Israel and one that fascinates, and fun-loving atmosphere, in which century Bauhaus architecture, dubbed bewilders and mesmerizes visitors. the difficult politics of the region rarely ‘the White City’, is not instantly Built a mere century ago on inhospitable intrudes and art, fashion, nightlife and attractive, but has made the city a World sand dunes, the city has risen to become beach fun prevail. This relaxed, open vibe Heritage Site, and its golden beaches, a thriving economic hub, and a center has seen Tel Aviv named ‘the gay capital lapped by the clear azure Mediterranean, of scientific, technological and artistic of the Middle East’ by Out Magazine, are beautiful places for beautiful people. -

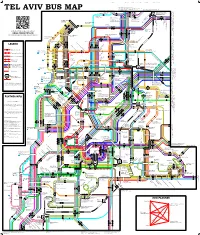

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

Module 3.2: Paradigms of Urban Planning

Module 3.2: Paradigms of Urban Planning Role Name Affiliation National Coordinator Subject Prof Sujata Patel Department of Sociology, Coordinator University of Hyderabad Paper Ashima Sood Woxsen School of Business Coordinator Indian Institute of Technology, Mandi Surya Prakash Content Writer Ashima Sood Woxsen School of Business Content Reviewer Prof Sanjeev Vidyarthi University of Illinois-Chicago Language Editor Ashima Sood Woxsen School of Business Technical Conversion Module Structure Sections and headings Introduction Planning Paradigms in the Anglophone World The Garden City 1 Neighbourhood unit as concept and planning practice Jane Jacobs New Urbanism Geddes in India Ideas in Practice Spatial planning in post-colonial India Modernism in the Indian city Neighbourhood unit in India In Brief For Further Reading Description of the Module Items Description of the Module Subject Name Sociology Paper Name Sociology of Urban Transformation Module Name/Title Paradigms of urban planning Module Id 3.2 Pre Requisites Objectives To develop an understanding of select urban planning paradigms in the Anglophone world To trace the influences and dominant frameworks guiding urban planning in contemporary India To critically evaluate the contributions of 2 planning paradigms to the present condition of Indian cities Key words Garden city; neighbourhood unit; New Urbanism; modernism in India; Jane Jacobs; Patrick Geddes (5-6 words/phrases) Introduction Indian cities are characterized by visual dissonance and stark juxtapositions of poverty and wealth. “If only the city was properly planned,” goes the refrain in response, whether in media, official and everyday discourse. Yet, this invocation of city planning, rarely harkens to the longstanding traditions of Indian urbanism – the remarkable drainage networks and urban accomplishments of the Indus Valley cities, the ghats of Varanasi, or the chowks and bazars of Shahjanahabad. -

Organic Evolution in the Work of Lewis Mumford 5

recovering the new world dream organic evolution in the work of lewis mumford raymond h. geselbracht To turn away from the processes of life, growth, reproduc tion, to prefer the disintegrated, the accidental, the random to organic form and order is to commit collective suicide; and by the same token, to create a counter-movement to the irrationalities and threatened exterminations of our day, we must draw close once more to the healing order of nature, modified by human design. Lewis Mumford "Landscape and Townscape" in The Urban Prospect (New York, 1968) The American Adam has been forced, in the twentieth century, to change in time, to recognize the inexorable movement of history which, in his original conception, he was intended to deny. The national mythology which posited his existence has also threatened in recent decades to become absurd. This mythology, variously called the "myth of the garden" or the "Edenic myth," accepts Hector St. John de Crevecoeur's judgment, formed in the 1780's, that man in the New World of America is as a reborn Adam, innocent, virtuous, who will forever remain free of the evils of European history and civilization. "Nature" —never clearly defined, but understood as the polar opposite of what was perceived as the evil corruption and decadence of civilization in the Old World—was the great New World lap in which this mythic self-concep tion sat, the simplicity of absences which assured the American of his eternal newness. The authors who have examined this mythic complex in recent years have usually resigned themselves to its gradual senescence and demise in the twentieth century. -

—PALESTINE and the MIDDLE EAST-N

PALESTINE AND MIDDLE EAST 409 —PALESTINE AND THE MIDDLE EAST-n By H. Lowenberg— PALESTINE THE YEAR BEGINNINO June, 1947, and ending May, 1948 was among the most crucial and critical periods in Palestine's modern history. The United Nations' historic partition decision of November 29, 1947, divided the year into two halves, each of different importance for the Yishuv and indeed for all Jewry: the uneasy peace before, and the commu- nal war after the UN decision; the struggle to find a solution to the Palestine problem before, and to prepare for and defend the Jewish state after that fateful day. Outside Palestine, in the Middle East as a whole, the UN partition decision and the Arab rebellion against it, left a mark scarcely less profound than in Palestine itself. UNSCOP On May 13, 1947, the special session of the General As- sembly of the United Nations created the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) with instructions to "prepare and report to the General Assembly and submit such proposals as it may consider appropriate for the solution of the problem of Palestine . not later than September ,1, 1947." In Palestine, the Arabs followed news of UNSCOP with apparent indifference. They adopted an attitude of hostil- ity towards the Committee, and greeted it with a two-day protest strike starting on June 15, 1947. Thereafter, they 410 AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK took no further notice of the Committee, the Arab press even obeying the Mufti's orders not to print any mention of UNSCOP. This worried the Committee, as boycott by one side to the dispute might mean a serious gap in its fact finding. -

Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality Environment and Sustainability Authority Editorial Board: Editor: Dr

A Report on the Environment and Sustainability in the City of Tel Aviv-Yafo Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality Environment and Sustainability Authority Editorial board: Editor: Dr. Orli Ronen, The Porter School of Environmental Studies, Tel Aviv University Eitan Ben Ami - Director of the Environment and Sustainability Authority Vered Crispin Ramati - Senior Projects Manager at Deputy CEO and Sustainability Programs Director, Operations Division Keren-Or Fish, The Center for Economic and Social Research Sivan 5778 – May 2018 Printed on recycled paper 2 Table of Contents Preface 4 Pertinent facts 6 Changes in the last decade 8 Innovations 2016-2017 10 Section 1 | Sustainable Municipal Management 14 Section 4 | Infrastructures and 41 Resources Urban strategy 15 Green building 44 Environmental protection and sustainability 17 at the Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality Waste 44 Mainstreaming and formalizing sustainability 18 Electricity 47 Transparency and public participation 20 Water consumption in the city 48 Section 2 | Urban Environmental Protection 24 Section 5 | A Sustainable Lifestyle 50 Air quality 26 A sustainability-enhancing urban space 54 Noise 29 Getting around the city 58 Innovations 2017 32 A sustainability-enhancing community 61 An active civil society 64 Section 3 | Nature and Ecology 33 Sustainable businesses in the city 66 Nature sites and open public areas 35 Yarkon River 38 The coast and the Mediterranean 38 Innovations 2017 40 3 Preface In December 2017, we approved the update of the Strategic Plan for Tel Aviv-Yafo. In the decade since the original Strategic Plan was approved in 2005, Tel Aviv-Yafo has become a sustainable city, a city whose residents and business establishments actively safeguard the environment and, by doing so, create a better quality of life.