Read the Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![“Impact Winter” Guest: Ben Murray [Intro Music] JOSH: Hello, You're Listening to the West Wing](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2813/impact-winter-guest-ben-murray-intro-music-josh-hello-youre-listening-to-the-west-wing-912813.webp)

“Impact Winter” Guest: Ben Murray [Intro Music] JOSH: Hello, You're Listening to the West Wing

The West Wing Weekly 6.09: “Impact Winter” Guest: Ben Murray [Intro Music] JOSH: Hello, you’re listening to The West Wing Weekly. I’m Joshua Malina. HRISHI: And I’m Hrishikesh Hirway. Today, we’re talking about Season 6 Episode 9. It’s called “Impact Winter”. JOSH: This episode was written by Debora Cahn. This episode was directed by Lesli Linka Glatter. This episode first aired on December 15th, 2004. HRISHI: Two episodes ago, in episode 6:07, the title was “A Change is Gonna Come,” and I think in this episode the changes arrive. JOSH: Aaaahhh. HRISHI: The President goes to China, but he is severely impaired by his MS. Charlie pushes C.J. to consider her next step after she steps out of the White House, and Josh considers his next step after it turns out Donna has already considered what her next step will be. JOSH: Indeed. HRISHI: Later in this episode we’re going to be joined by Ben Murray who made his debut on The West Wing in the last episode. He plays Curtis, the president’s new personal assistant to replace Charlie. JOSH: A man who has held Martin Sheen in his arms. I mean, I’ve done that off camera, but he did it on television. HRISHI: [Laughs] Little do our listeners know that Martin Sheen insists on being carried everywhere. JOSH: That’s right. I was amazed all these years later when Martin showed up for his interview with us that Ben was carrying him. That was the first time we met him. -

Under the Silver Lake

Presents UNDER THE SILVER LAKE A film by David Robert Mitchell 139 mins, USA, 2018 Language: English Official Selection: 2018 Festival de Cannes – Competition – World Premiere 2018 Fantasia Festival – Camera Lucida – Canadian Premiere Distribution Publicity Mongrel Media Inc Bonne Smith 1352 Dundas St. West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1Y2 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Twitter: @starpr2 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com Synopsis From the dazzling imagination that brought you It Follows and The Myth of the American Sleepover comes a delirious neo-noir thriller about one man’s search for the truth behind the mysterious crimes, murders, and disappear- ances in his East L.A. neighborhood. Sam (Andrew Garfield) is a disenchanted 33 year old who discovers a mys- terious woman, Sarah (Riley Keough), frolicking in his apartment’s swimming pool. When she vanishes, Sam embarks on a surreal quest across Los An- geles to decode the secret behind her disappearance, leading him into the murkiest depths of mystery, scandal, and conspiracy in the City of Angels. From writer-director David Robert Mitchell comes a sprawling and unexpect- ed detective thriller about the Dream Factory and its denizens—dog killers, aspiring actors, glitter-pop groups, nightlife personalities, It girls, memorabilia hoarders, masked seductresses, homeless gurus, reclusive songwriters, sex workers, wealthy socialites, topless neighbors, and the shadowy billionaires floating above (and underneath) it all. Mining a noir tradition extending from Kiss Me Deadly and The Long Good- bye to Chinatown and Mulholland Drive, Mitchell uses the topography of Los Angeles as a backdrop for a deeper exploration into the hidden meaning and secret codes buried within the things we love. -

Jonathan Arthur Resume 3-2010

JonathanArthur STUNTMEN’S ASSOCIATION Joni’s 818-980-2123 | Cell 818-926-9138 | [email protected] | SAG/AFTRA | 5’9” 160 lbs Film: · Gulliver’s Travels Stunt Performer Doug Coleman · Pizza Man Stunt Coordinator Joe Eckhart/RockOn! Films · Hall Pass Stunt Double – Derek Waters Tierre Turner · Piranha 3-D Stunt Double – Steven McQueen Alex Daniels Stunt Double – Adam Scott · Sucker Punch Stunt Coordinator: Motion Capture Cruel & Unusual Films/Warner Bros. · Dinner for Schmucks Stunt Double – Patrick Fischler Tom Harper · Dam Love Stunt Performer Spiro Razatos · The Surrogates Stunt Actor – Featured Cop Jery Hewitt · I Love You, Man Stunt Double – Paul Rudd Alex Daniels · Filth to Ashes, Flesh to Dust Stunt Coordinator Paul Morrell/Jeoa Productions · The Pretender (test) Asst. Stunt Coordinator Eddie Yansick · The Gothem Project Stunt Utility Eddie Yansick · Skylar Stunt Performer Tim Soergel · Tell-Tale Stunt Double – Dallas Roberts Doug Crosby · The Taking of Pelham 123 Stunt Performer Chuck Picerni · Avatar Stunt Utility Garrett Warren · Tintin (Spielberg/Jackson) Stunt Utility Garrett Warren · The Wrestler Stunt Performer Doug Crosby · Weather Girl Stunt Coordinator Blayne Weaver/Secret Id. Prod · Indiana Jones 4 Stunt Performer Gary Powell · Cloverfield Stunt Coordinator: NY Unit J.J. Abrams/Bad Robot Stunt Double/ND Stunts · The Heartbreak Kid Stunt Double: 2nd Unit – Ben Stiller Tierre Turner · Next Stunt Driver/ND Stunts R.A. Rondell Stunt Double – Jose Zuniga Eddie Yansick · Rampage Superstar Stunt Coordinator Michael Ballaschke/Chapman · Coach Shane (video) Stunt Coordinator/Ice Hockey T.A. Drew Renuad/Enlighten Ent. · I Kicked Luis Guzman (short) Stunt Coordinator Sherwin Shilati/Hendricks-Shilati Co. Television: · Bones Stunt Double – T.J. -

Broadway Initiative Marks a Decade of Fostering Historic Downtown's

VOLUME 31 SEP OCT 2009 NUMBER 5 Get Ready to Celebrate! The 1960s Turn 50 by Trudi Sandmeier In 2010, buildings constructed in 1960 will turn fifty. While turning fifty strikes fear in the hearts of many Angelenos, it’s actually good for important buildings. In historic preservation, fifty years is the general threshold for when buildings and structures may be officially considered old enough to have acquired historic significance, par- ticularly in terms of the National Register of His- toric Places. Los Angeles has always pushed the LEFT: Historic photo of a bustling Broadway at Seventh Street, with Loew’s State Theatre in the foreground. Photo envelope by recognizing places and spaces that courtesy Los Angeles Public Library. RIGHT: Grand Central Market. Photo by LAC staff. are significant despite their being younger than fifty, but crossing this line means it won’t be such a struggle. Broadway Initiative Marks a Decade of The decade of the 1960s was an amazing time. Against the national backdrop of the Kennedy era, Fostering Historic Downtown’s the civil rights movement, the space race, and the Age of Aquarius, Los Angeles developed its free- Renaissance way system, the aerospace industry flourished, and the population boomed. by Cindy Olnick Can’t think of any ’60s buildings that are his- In 1999, the Los Angeles Conservancy set an ambitious agenda to help foster historic downtown’s toric? What about the iconic 1961 LAX Theme renewal, naming it the Broadway Initiative. Ten years later—thanks to the heroic and ongoing efforts of Building by powerhouse architects William Pereira, many, many people—the city’s Historic Core has thousands of residents, a vibrant arts and culture scene, Charles Luckman, Paul Williams, and Welton new services and amenities, and powerful momentum for ongoing renewal. -

Lan Switch Digital Manu

BACKSTORY In the years after World War II, while many struggled to rebuild their lives in a devastated economy, Los Angeles embraced an era of unprec - edented growth and prosperity, and Hollywood became a shining beacon of the American Dream to the rest of the world. Yet beneath the glitz and glamour lay a darker reality: a burgeoning drug trade, a movie industry relentlessly preying on naïve young girls, rampant corruption at every level of police and government, and thousands of demobilized troops trying to readjust to civilian life and leave the horrors of war behind them. After years of fighting in the Pacific Theater of World War II, one such young man, Marine Lieutenant Cole Phelps, was awarded one of the Navy’s highest honors, the Silver Star, and was honorably discharged. Keen to continue serving his country on home soil, Cole signed up with the L.A.P.D., a police force suffering a public rela- tions crisis amid accusations of corruption and brutality. A young, decorated war hero could be just what the department needs to turn the tide of public opinion. The powers that be are watching… 03 02 L Button R Button ZL Button ZR Button – Button + Button X Button Left Stick A Button SL Button SR Button B Button Release Player LED Y Button Button Directional Right Stick Buttons SYNC Button Capture Button SR Button SL Button Rail HOME Button IR Motion Camera GENERAL CONTROLS GENERAL CONTROLS GENERAL CONTROLS (GUN FIGHT) TOUCH CONTROLS (ON FOOT) LEFT STICK Movement / Rotate RIGHT Call Partner ZL BUTTON Aim Weapon SINGLE TAP Movement Objects -

Lynn Teen Killed in Saugus Head-On Caused by Fleeing Robbery Suspect

DEALS OF THE $DAY$ PG. 3 THURSDAY JUNE 10, 2021 DEALS OF THE Summer fun $DAY$ will resume PG. 3 in Lynn DEALS By Allysha Dunnigan ITEM STAFF OF THE LYNN — After the pandemic put $DAY$ much of its programming on hold PG. 3 last year, the city plans to bring back summer fun with a variety of youth programs from June to August. For ages 13 to 18, Thurgood Mar- shall Middle School will be hosting a free summer teen drop-in center in DEALS its gym from June 25 to Aug. 27. Every Friday from 5:30 to 9:30 OF THE p.m., the gym will offer a space for $DAY$ teens to play sports, listen to music PG. 3 and hear guest speakers, all in the PG. 3 air-conditioned facility. ITEM PHOTO | SPENSER HASAK For ages 6 to 18, the Bowzer Com- plex on O’Callaghan Way will host The aftermath of a fatal head-on collision between two sedans on Route 107 north in Saugus on Wednesday. an evening tennis program starting from July 7-30. DEALS Sponsored by the Lynn Parks and Recreation Department, this clinic Lynn teen killed in Saugus head-onOF THE will run on Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays from 4:30 to 7:30 p.m., $DAY$ unless canceled due to inclement PG. 3 weather. caused by fleeing robbery suspect The instructor for this program will be Alex Show, a tennis veteran By Tréa Lavery The Saugus Police Department re- mile south of the Ballard Street inter- who played on her high-school var- ITEM STAFF sponded to a report of a robbery at section. -

PPTFH Reports Efforts Amid COVID-19 Outbreak

20 Pages Thursday, April 9, 2020 ◆ Pacific Palisades, California $1.50 COVID-19: Palisadians Encouraged Pali High Board of Trustees to Wear Face Coverings Assesses Grading System Concerns By SARAH SHMERLING to 3D print PPE in bulk response ously crowded,” Garcetti reported During Safer at Home Order Editor-in-Chief to the COVID-19 crisis.” that physical distancing plans to Public Health is also recom- keep communities safe have been By JENNIKA INGRAM s safer at home orders in place mending residents skip grocery reviewed. Though the Pacific Pal- Reporter across the city of Los Ange- shopping and other tasks that are isades Farmers Market remains Ales extend into the fourth week, technically allowed but put them closed due to LAUSD orders, 31 he Palisades Charter High residents are now encouraged by in a space with other people this farmers markets have submitted School Board of Trustees the Centers for Disease Control week whenever possible. plans for approval of safe opera- Tmet virtually on March 31—the and Prevention and County of Los “As we expect to see a signifi- tions—with 16 able to reopen as first-ever meeting of the board Angeles Public Health to wear cant increase in cases over the next of Monday. through Zoom. non-medical face coverings to help few weeks, we are asking that ev- The county continues to pro- With 48 participants, the meet- reduce the spread of COVID-19. eryone avoid leaving their homes vide free testing to residents with ing included more participants The coverings can be bandan- for anything except the most urgent COVID-19 symptoms. -

2015-2016 Newsletter

CHANGING THE WORLD STARTS AT HOME Photo Credit: Ben Miller DOES APCH REALLY MATTER? How do we quantify the impact schoolers graduate. What is the value of providing of our work? That’s the million-dollar More than 300 students from South such an array of FREE programs for question these days for nonprofits – L.A. have received APCH scholarships youth and families? How much do our funders want to know if they are mak- totaling more than $3,000,000 for programs prevent in social services • ing a good investment. Fair enough, tuition, living expenses and books. paid out, unemployment and disability there are a lot of things we actually Nationally, 2/3 of minority students benefits? Law enforcement, justice who are first in their families to go A PLACE CALLED HOME can count… system and incarceration costs? Graf- 80% of the families we serve live on to college drop out in their first year. fiti abatement, property loss, violent annual incomes of under $23,000. When we send a student to college we crime? Hospitalizations, drug rehab We serve an average of 300 youth provide wraparound support. Result: programs, and funerals? How much tax 8-21 years old each day (more if you 90% retention. revenue is generated when our gradu- count our 74 college scholars) and 900- We serve 75-80,000 meals per year, ates get good jobs and pay into the 1,000 unique individual youth annually. and we distribute 5,000 bags of grocer- system? What is the value of the inven- Over 22 years, we’ve served more than ies to families in need. -

Halloween Kandace Springs

JAKE GYLLENHAAL IS THE October 23 - November 5, 2014 | Vol. 24 Issue 18 | Always Free THE SECRET TO AWESOME COSTUME MAKEUP! WHERE TO GO FOR HALLOWEEN IN L.A. CHATTING WITH SINGER KANDACE SPRINGS: SHE’S GOT SOUL ©2014 CAMPUS CIRCLE • (323) 939-8477 • 5042 WILSHIRE BLVD., #600 LOS ANGELES, CA 90036 • PLUS: RETHINKING RELATIONSHIPS IN COLLEGE WWW.CAMPUSCIRCLE.COM “DARING, DEVASTATING, HOWLINGLY FUNNY.’’ -PETER TRAVERS, ‘‘SENSATIONAL! NOT QUITE LIKE ANYTHING YOU’VE SEEN AT THE MOVIES.” -STEVEN J. SNYDER, ‘‘MICHAEL KEATON SOARS.’’ -LOU LUMENICK, ‘‘BRILLIANT ON SO MANY LEVELS.’’ -BETSY SHARKEY, ‘‘SUPREMELY EXHILARATING.’’ -CLAUDIA PUIG, UCLA,USC_BDM_1024 WEST LOS ANGELES HOLLYWOOD CENTURY CITY SHERMAN OAKS IRVINE PASADENA EXCLUSIVE ENGAGEMENTS at W. Pico at Sunset & Vine AMC Century City 15 at The Sherman Oaks Galleria Edwards University ArcLight Cinemas & Westwood (310) 470-0492 (323) 464-4226 (888) AMC-4FUN (818) 501-0753 Town Center 6 Pasadena NOW PLAYING (800) FANDANGO #143 (626) 568-9651 Campus Circle WEDNESDAY 10/22 WEST LOS ANGELES HOLLYWOOD CENTURY CITY5 COL. SHERMAN(10”) X 12.5” OAKS TM AMC ALL.BDM-R1.1022.CAM at The at W. Pico & Westwood at Sunset & Vine Century City 15 Sherman Oaks Galleria (310) 470-0492 (323)4 464-4226 COLOR(888) AMC-4FUN - (818)REVISE 501-0753 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS October 23 - November 5, 2014 WHAT’SINSIDE Vol. 24 Issue 18 Editor-in-Chief Sydney Champion [email protected] 15 Art Director 08 Sean Michael Beyer NEWS Film Editor 04 That Latest from L.A. and Beyond [email protected] 05 Scholars from War-Torn Countries Music Editor Flee to U.S. -

Wick Retires from Nursing After 39 Years

Snow likely High: 26 | Low: 12 | Details, page 2 DAILY GLOBE yourdailyglobe.com Thursday, December 29, 2016 75 cents CHRISTMAS BABY Wick retires Ironwood area couple receives from nursing special delivery on Christmas after 39 years By RALPH ANSAMI By LARRY HOLCOMBE muscle tone, [email protected] [email protected] and preserving IRONWOOD — A Christmas HURLEY — Zona Wick is bone density. delivery was very special to an retiring from 39 years of nursing Working with Ironwood area couple this year. today. For the last 10 and half partners at the On Christmas Day, Olivia years, she worked as Iron Coun- Aging Unit and Reini and Darryl Anderson Jr. ty’s Health Officer and director Aging and Dis- went to Aspirus Ironwood Hospi- of the Health Department. a b i l i t y tal because Olivia was experi- There have been many chal- Resource Cen- encing back pains while preg- lenges in Iron County over those ter are key to nant. years, but Wick said she and her the success of small, but able, staff met them Zona these pro- The obstetrics department Wick sent her to the emergency room head on, often with help from grams.” because she wasn’t in labor and others in the community. Wick is her baby was due on Dec. 27. On Wednesday, she shared quick to divert praise to her staff Reini had been in the hospital with the Daily Globe some of the and others. a couple of times previously for lessons she learned from that “Our board of health and full the same lower back pains. -

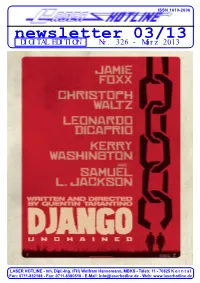

Newsletter 03/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 03/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 326 - März 2013 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 03/13 (Nr. 326) März 2013 Funny Fatty Wann haben Sie zuletzt eine übergewichtige Frau gesehen? sonst?), unter anderem als Schönling Ryan Reynolds Ehefrau. Heute Morgen in der U-Bahn? Gestern im Supermarkt? Gerade Und wissen Sie was? Es funktioniert! Im echten Leben sind dicke eben am Briefkasten? Die Chancen sind gut, dass Sie dicken Frauen nämlich Ehefrauen, Arbeiterinnen, Freundinnen, Frauen regelmäßig über den Weg laufen. In Hollywood, so Chefinnen und alles andere, was dünne auch sind. Ok, vielleicht scheint es, ist diese Spezies allerdings extrem selten. In einem abgesehen von Turnerinnen. Der Punkt ist: Dicke können mehr, Land, in dem 70% der Menschen zu viel auf die Waage packen, als nur der Belustigung der Normalen zu dienen. Sie sind Teil des macht die Traumfabrik ihrem Namen alle Ehre: Sie träumt eine Lebens und sie sind berechtigt zu leben. In Hollywood ist dies Größe-34-Welt vor. Selbstverständlich gilt dieser absurde noch nicht angekommen. Dort blödelt sich Melissa McCarthy Standard nur für Frauen. Männer wie John Goodman oder Vincent derzeit durch Identity Thief und musste sich dafür von Filmkritiker D’Onofrio gelten als “gut beinand” (wie man in meiner Heimat Rex Reed anhören, dass sie ein Nilpferd und eine Dampfwalze München sagen würde) und sind ernst zu nehmen. -

To Download the Press

Sometimes the most powerful words are the ones you’re still searching for. KAIROS PRODUCTIONS PRESENTS Language Arts Run Time: 127 min Genre: Family Drama Year: 2020 Language: English Country of Origin: United States Format: 4K, aspect ratio 1:1.78 SALES: Larry Estes, (206) 686-1572, larry@welbfilm.com MEDIA: Carol Roscoe, (206) 769-6148, [email protected] Language Arts Poster Files Trailer Website IMDB: Language Arts Press Images available here All photos credited to Annabel Clark Synopsis Logline: When a student proposes a project involving autistic youth and senior dementia patients, high school English teacher Charles Marlow must confront the indelible mark that autism has made on the story of his life. Short: It’s 1993, and high school English teacher Charles Marlow, (Ashley Zukerman) has spent decades shrinking from life, hiding away from the disappointments that have trailed him. When his student/protegé Romy (Aishe Keita) proposes a photojournalism project documenting collaborations between autistic youth and senior dementia patients, Charles tailspins into his past, through a series of interlocking timelines, confronting the errors of his youth. In a 1962 Seattle classroom, young Charles (Elliott Smith) befriends an autistic child, Dana (Lincoln Lambert), with shocking consequences. In the 1980s, Charles and his wife Alison (Sarah Shahi) struggle to comprehend their own child’s autism, resulting in the destruction of their marriage. Now, as his student confronts, head-on, the challenges of working with neuro-diverse individuals, Charles determines to deal with his haunting failures. Awkwardly, with many revisions, he sets about repairing his own story. Inspired by his student’s art, Charles learns to see the world around him anew, make peace with the errors of the past, and incorporate new ways of listening and connecting with the people he loves.