Arxiv:2007.07560V4 [Math.LO] 8 Oct 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addiction in Contemporary Mathematics FINAL 2020

Addiction in Contemporary Mathematics Newcomb Greenleaf Goddard College [email protected] Abstract 1. The Agony of Constructive Math 2. Reductio and Truth 3. Excluding the Middle 4. Brouwer Seen from Princeton 5. Errett Bishop 6. Brouwer Encodes Ignorance 7. Constructive Sets 8. Kicking the Classical Habit 9. Schizophrenia 10. Constructive Mathematics and Algorithms 11. The Intermediate Value Theorem 12. Real Numbers and Complexity 13. Natural Deduction 14. Mathematical Pluralism 15. Addiction in History of Math Abstract In 1973 Errett Bishop (1928-1983) gave the title Schizophrenia in Contemporary Mathematics to his Colloquium Lectures at the summer meetings of the AMS (American Mathematical Society). It marked the end of his seven-year campaign for Constructive mathematics, an attempt to introduce finer distinctions into mathematical thought. Seven years earlier Bishop had been a young math superstar, able to launch his revolution with an invited address at the International 1 Congress of Mathematicians, a quadrennial event held in Cold War Moscow in 1966. He built on the work of L. E. J. Brouwer (1881-1966), who had discovered in 1908 that Constructive mathematics requires a more subtle logic, in which truth has a positive quality stronger than the negation of falsity. By 1973 Bishop had accepted that most of his mathematical colleagues failed to understand even the simplest Constructive mathematics, and came up with a diagnosis of schizophrenia for their disability. We now know, from Andrej Bauer’s 2017 article, Five Stages of Accepting Constructive Mathematics that a much better diagnosis would have been addiction, whence our title. While habits can be kicked, schizophrenia tends to last a lifetime, which made Bishop’s misdiagnosis a very serious mistake. -

Computability and Analysis: the Legacy of Alan Turing

Computability and analysis: the legacy of Alan Turing Jeremy Avigad Departments of Philosophy and Mathematical Sciences Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, USA [email protected] Vasco Brattka Faculty of Computer Science Universit¨at der Bundeswehr M¨unchen, Germany and Department of Mathematics and Applied Mathematics University of Cape Town, South Africa and Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences Cambridge, United Kingdom [email protected] October 31, 2012 1 Introduction For most of its history, mathematics was algorithmic in nature. The geometric claims in Euclid’s Elements fall into two distinct categories: “problems,” which assert that a construction can be carried out to meet a given specification, and “theorems,” which assert that some property holds of a particular geometric configuration. For example, Proposition 10 of Book I reads “To bisect a given straight line.” Euclid’s “proof” gives the construction, and ends with the (Greek equivalent of) Q.E.F., for quod erat faciendum, or “that which was to be done.” arXiv:1206.3431v2 [math.LO] 30 Oct 2012 Proofs of theorems, in contrast, end with Q.E.D., for quod erat demonstran- dum, or “that which was to be shown”; but even these typically involve the construction of auxiliary geometric objects in order to verify the claim. Similarly, algebra was devoted to developing algorithms for solving equa- tions. This outlook characterized the subject from its origins in ancient Egypt and Babylon, through the ninth century work of al-Khwarizmi, to the solutions to the quadratic and cubic equations in Cardano’s Ars Magna of 1545, and to Lagrange’s study of the quintic in his R´eflexions sur la r´esolution alg´ebrique des ´equations of 1770. -

Mass Problems and Intuitionistic Higher-Order Logic

Mass problems and intuitionistic higher-order logic Sankha S. Basu Department of Mathematics Pennsylvania State University University Park, PA 16802, USA http://www.personal.psu.edu/ssb168 [email protected] Stephen G. Simpson1 Department of Mathematics Pennsylvania State University University Park, PA 16802, USA http://www.math.psu.edu/simpson [email protected] First draft: February 7, 2014 This draft: August 30, 2018 Abstract In this paper we study a model of intuitionistic higher-order logic which we call the Muchnik topos. The Muchnik topos may be defined briefly as the category of sheaves of sets over the topological space consisting of the Turing degrees, where the Turing cones form a base for the topology. We note that our Muchnik topos interpretation of intuitionistic mathematics is an extension of the well known Kolmogorov/Muchnik interpretation of intuitionistic propositional calculus via Muchnik degrees, i.e., mass prob- lems under weak reducibility. We introduce a new sheaf representation of the intuitionistic real numbers, the Muchnik reals, which are different from the Cauchy reals and the Dedekind reals. Within the Muchnik topos we arXiv:1408.2763v1 [math.LO] 12 Aug 2014 obtain a choice principle (∀x ∃yA(x,y)) ⇒∃w ∀xA(x,wx) and a bound- ing principle (∀x ∃yA(x,y)) ⇒ ∃z ∀x ∃y (y ≤T (x,z) ∧ A(x,y)) where x,y,z range over Muchnik reals, w ranges over functions from Muchnik reals to Muchnik reals, and A(x,y) is a formula not containing w or z. For the convenience of the reader, we explain all of the essential back- ground material on intuitionism, sheaf theory, intuitionistic higher-order logic, Turing degrees, mass problems, Muchnik degrees, and Kolmogorov’s calculus of problems. -

A Non-Standard Analysis of a Cultural Icon: the Case of Paul Halmos

Log. Univers. c 2016 Springer International Publishing DOI 10.1007/s11787-016-0153-0 Logica Universalis A Non-Standard Analysis of a Cultural Icon: The Case of Paul Halmos Piotr Blaszczyk, Alexandre Borovik, Vladimir Kanovei, Mikhail G. Katz, Taras Kudryk, Semen S. Kutateladze and David Sherry Abstract. We examine Paul Halmos’ comments on category theory, Dedekind cuts, devil worship, logic, and Robinson’s infinitesimals. Hal- mos’ scepticism about category theory derives from his philosophical po- sition of naive set-theoretic realism. In the words of an MAA biography, Halmos thought that mathematics is “certainty” and “architecture” yet 20th century logic teaches us is that mathematics is full of uncertainty or more precisely incompleteness. If the term architecture meant to im- ply that mathematics is one great solid castle, then modern logic tends to teach us the opposite lession, namely that the castle is floating in midair. Halmos’ realism tends to color his judgment of purely scientific aspects of logic and the way it is practiced and applied. He often ex- pressed distaste for nonstandard models, and made a sustained effort to eliminate first-order logic, the logicians’ concept of interpretation,and the syntactic vs semantic distinction. He felt that these were vague,and sought to replace them all by his polyadic algebra. Halmos claimed that Robinson’s framework is “unnecessary” but Henson and Keisler argue that Robinson’s framework allows one to dig deeper into set-theoretic resources than is common in Archimedean mathematics. This can poten- tially prove theorems not accessible by standard methods, undermining Halmos’ criticisms. Mathematics Subject Classification. -

Foreword to Foundations of Constructive Analysis

Foreword Michael Beeson 1 Significance of this book This book made an important contribution to a debate about the meaning of mathematics that started about a century be- fore its 1967 publication, and is still going on today. That de- bate is about the meaning of \non-constructive" proofs, in which one proves that something exists by assuming it does not exist, and then deriving a contradiction, without showing a way to construct the thing in question. As an example of the kind of proof in question, we might consider the \fundamental theorem of algebra", according to which every non-constant polynomial equation f(z) = 0 has a solution (among the complex numbers). To prove this theorem, do we have to show how to calculate a solution? Or is it enough to derive a contradiction from the assumption that f(z) is never zero? My favorite quotation from Errett Bishop is this: Meaningful distinctions need to be preserved.[5] He is talking about the distinction between constructive and non-constructive proof. This quotation encapsulates his ap- proach to the matter. His predecessors had taken an all-or- nothing approach, either maintaining that only constructive proofs are correct, and non-constructive proofs are illusory or just wrong, or else maintaining that non-constructive proofs are valid, and while computational information might be interesting in special cases, it is of no philosophical significance. There was, natu- rally, very little productive interplay between these camps, only exchanges of polemics. i Bishop changed that situation with this book. He simply applied a technique that has been used many times in mathe- matics: he worked in the common ground, so that both \classical mathematics" (that is, with proofs of existence by contradiction allowed) and previously existing varieties of constructive mathe- matics (which made claims contradicting classical mathematics) could be viewed as generalizing the body of mathematics that Bishop developed in this book. -

![Arxiv:1607.00149V1 [Math.HO] 1 Jul 2016 ..Ctgr Hoyvee Ysm 6 5 4 6 4 Some by Viewed Theory Theory Category Category and Cuts 4.1](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8784/arxiv-1607-00149v1-math-ho-1-jul-2016-ctgr-hoyvee-ysm-6-5-4-6-4-some-by-viewed-theory-theory-category-category-and-cuts-4-1-4678784.webp)

Arxiv:1607.00149V1 [Math.HO] 1 Jul 2016 ..Ctgr Hoyvee Ysm 6 5 4 6 4 Some by Viewed Theory Theory Category Category and Cuts 4.1

A NON-STANDARD ANALYSIS OF A CULTURAL ICON: THE CASE OF PAUL HALMOS PIOTR BLASZCZYK, ALEXANDRE BOROVIK, VLADIMIR KANOVEI, MIKHAIL G. KATZ, TARAS KUDRYK, SEMEN S. KUTATELADZE, AND DAVID SHERRY Abstract. We examine Paul Halmos’ comments on category the- ory, Dedekind cuts, devil worship, logic, and Robinson’s infinites- imals. Halmos’ scepticism about category theory derives from his philosophical position of naive set-theoretic realism. In the words of an MAA biography, Halmos thought that mathematics is “cer- tainty” and “architecture” yet 20th century logic teaches us is that mathematics is full of uncertainty or more precisely incomplete- ness. If the term architecture meant to imply that mathematics is one great solid castle, then modern logic tends to teach us the op- posite lession, namely that the castle is floating in midair. Halmos’ realism tends to color his judgment of purely scientific aspects of logic and the way it is practiced and applied. He often expressed distaste for nonstandard models, and made a sustained effort to eliminate first-order logic, the logicians’ concept of interpretation, and the syntactic vs semantic distinction. He felt that these were vague, and sought to replace them all by his polyadic algebra. Hal- mos claimed that Robinson’s framework is “unnecessary” but Hen- son and Keisler argue that Robinson’s framework allows one to dig deeper into set-theoretic resources than is common in Archimedean mathematics. This can potentially prove theorems not accessible by standard methods, undermining Halmos’ criticisms. Keywords: Archimedean axiom; bridge between discrete and continuous mathematics; hyperreals; incomparable quantities; in- dispensability; infinity; mathematical realism; Robinson. -

Erreh Bishop: Reflections on Him and His Research

ErreH Bishop: Reflections on Him and His Research Proceedings of the Memorial Mleeting for Errett Bishop September 24, 1983 University of California, San Diego Murray Rosenblatt Editor I C American Mathematical Society http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/conm/039 Recent Titles in This Series 164 Cameron Gordon, Yoav Moriah, and Bronislaw Wajnryb, Editors, Geometric topology, 1994 163 ZhongCi Shi and Chnng-Chnn Yang, Editors, Computational mathematics in China, 1994 162 ChCiberto, E. Laura Livorni, and Andrew J. Sommese, Editors, Classification of algebraic varieties, 1994 161 Pad A. Schweitzer, S. J, Steven Hnrder, Nathan Moreira dos Santos, and J& Luis Arraut, Editors, Differential topology, foliations, and group actions, 1994 160 NiiKamran and Peter J. Olver, Editors, Lie algebras, cohomology, and new applications to quantum mechanics, 1994 159 WiJ. Heinzer, Craig L Huneke, and Judith D. Sally, Editors, Commutative algebra: Syzygies, multiplicities, and birational algebra, 1994 158 Eric M. Friedlander and Mark E. Mahowald, Editors, Topology and representation theory, 1994 157 AUio Qnarteroni, Jacques Perianx, Ynri A. Knznetsov, and Olof B. Widlund, Editors, Domain decomposition methods in science and engineering, 1994 156 Stwen R. Givant, The structure of relation algebras generated by relativizations, 1994 155 WiB. Jacob, Tsit-Ynen Lam, and Robert 0. Robson, Editors, Recent advances in real algebraic geometry and quadratic forms, 1994 154 Michael Eastwood, Joseph Wolf, and Roger Zieran, Editors, The Penrose transform and analytic cohomology in representation theory, 1993 153 Richard S. Elman, Murray M. Schacher, and V. S. Varadarajan, Editors, Linear algebraic groups and their representations, 1993 152 Christopher K. McCord, Editor, Nielsen theory and dynarnical systems, 1993 15 1 Matntyahn Rnbin, The reconstruction of trees from their automorphism groups, 1993 150 Carl-Friedrich Biidigheirner and Richard M. -

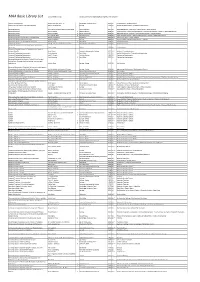

MAA Basic Library List Last Updated 1/23/18 Contact Darren Glass ([email protected]) with Questions

MAA Basic Library List Last Updated 1/23/18 Contact Darren Glass ([email protected]) with questions Additive Combinatorics Terence Tao and Van H. Vu Cambridge University Press 2010 BLL Combinatorics | Number Theory Additive Number Theory: The Classical Bases Melvyn B. Nathanson Springer 1996 BLL Analytic Number Theory | Additive Number Theory Advanced Calculus Lynn Harold Loomis and Shlomo Sternberg World Scientific 2014 BLL Advanced Calculus | Manifolds | Real Analysis | Vector Calculus Advanced Calculus Wilfred Kaplan 5 Addison Wesley 2002 BLL Vector Calculus | Single Variable Calculus | Multivariable Calculus | Calculus | Advanced Calculus Advanced Calculus David V. Widder 2 Dover Publications 1989 BLL Advanced Calculus | Calculus | Multivariable Calculus | Vector Calculus Advanced Calculus R. Creighton Buck 3 Waveland Press 2003 BLL* Single Variable Calculus | Multivariable Calculus | Calculus | Advanced Calculus Advanced Calculus: A Differential Forms Approach Harold M. Edwards Birkhauser 2013 BLL** Differential Forms | Vector Calculus Advanced Calculus: A Geometric View James J. Callahan Springer 2010 BLL Vector Calculus | Multivariable Calculus | Calculus Advanced Calculus: An Introduction to Analysis Watson Fulks 3 John Wiley 1978 BLL Advanced Calculus Advanced Caluculus Lynn H. Loomis and Shlomo Sternberg Jones & Bartlett Publishers 1989 BLL Advanced Calculus Advanced Combinatorics: The Art of Finite and Infinite Expansions Louis Comtet Kluwer 1974 BLL Combinatorics Advanced Complex Analysis: A Comprehensive Course in Analysis, -

Abraham Robinson and Nonstandard Analysis: History, Philosophy, and Foundations of Mathematics

---------Joseph W. Dauben -------- Abraham Robinson and Nonstandard Analysis: History, Philosophy, and Foundations of Mathematics Mathematics is the subject in which we don't know* what we are talking about. - Bertrand Russell * Don't care would be more to the point. -Martin Davis I never understood why logic should be reliable everywhere else, but not in mathematics. -A. Heyting 1. Infinitesimals and the History of Mathematics Historically, the dual concepts of infinitesimals and infinities have always been at the center of crises and foundations in mathematics, from the first "foundational crisis" that some, at least, have associated with discovery of irrational numbers (more properly speaking, incommensurable magnitudes) by the pre-socartic Pythagoreans1, to the debates that are cur rently waged between intuitionists and formalist-between the descendants of Kronecker and Brouwer on the one hand, and of Cantor and Hilbert on the other. Recently, a new "crisis" has been identified by the construc tivist Erret Bishop: There is a crisis in contemporary mathematics, and anybody who has This paper was first presented as the second of two Harvard Lectures on Robinson and his work delivered at Yale University on 7 May 1982. In revised versions, it has been presented to colleagues at the Boston Colloquim for the Philosophy of Science (27 April 1982), the American Mathematical Society meeting in Chicago (23 March 1985), the Conference on History and Philosophy of Modern Mathematics held at the University of Minnesota (17-19 May 1985), and, most recently, at the Centre National de Recherche Scientifique in Paris (4 June 1985) and the Department of Mathematics at the University of Strassbourg (7 June 1985). -

Foundations of Constructive Mathematics

Michael 1. Beeson Foundations of Constructive Mathematics Metamathematical Studies Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg NewYork Tokyo Michael J. Beeson Department of Mathematics and Computer Science San Jose State University San Jose, CA 95192, USA AMS Subject Classification (1980): 03F50, 03F55, 03F60, 03F65 ISBN-13: 978-3-642-68954-3 e-ISBN-13: 978-3-642-68952-9 DOl: 10.1007/978-3-642-68952-9 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Beeson, Michael J., 1945-. Foundations of constructive mathematics. (Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete; 3. Folge, Bd. 6) Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. I. Constructive mathematics. 1. Title. II. Series. QA9.56.B44 1985 511.3 84-10583 ISBN 0-387-12173-0 (U.S.) This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically those of translation, reprinting, re-use of illus· trations, broadcasting, reproduction by photocopying machine or similar means, and storage in data banks. Under § 54 of the German Copyright Law where copies are made for other than private use, a fee is payable to "Verwertungsgesellschaft Wort", Munich. © by Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 1985 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1985 Typesetting, printing and binding: Universitiitsdruckerei H. Stiirtz AG, 8700 Wiirzburg 2141/3140-543210 Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete 3. Folge . Band 6 A Series of Modem Surveys in Mathematics Editorial Board E. Bombieri, Princeton S. Feferman, Stanford N.H. Kuiper, Bures-sur-Yvette P. Lax, NewYork R Remmert (Managing Editor), Miinster W. Schmid, Cambridge, Mass. J-P. Serre, Paris 1. Tits, Paris This book is dedicated to the memories of Errett Bishop and Arend Heyting Table of Contents Introduction XIII User's Manual XVIII Common Notations XX Acknowledgements XXII Part One. -

The Prehistory of the Subsystems of Second-Order Arithmetic

The Prehistory of the Subsystems of Second-Order Arithmetic Walter Dean* and Sean Walsh** December 19, 2016 Abstract This paper presents a systematic study of the prehistory of the traditional subsys- tems of second-order arithmetic that feature prominently in the reverse mathematics program of Friedman and Simpson. We look in particular at: (i) the long arc from Poincar´eto Feferman as concerns arithmetic definability and provability, (ii) the in- terplay between finitism and the formalization of analysis in the lecture notes and publications of Hilbert and Bernays, (iii) the uncertainty as to the constructive status of principles equivalent to Weak K¨onig'sLemma, and (iv) the large-scale intellectual backdrop to arithmetical transfinite recursion in descriptive set theory and its effec- tivization by Borel, Lusin, Addison, and others. * Department of Philosophy, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL, United Kingdom, E-mail: [email protected] **Department of Logic and Philosophy of Science, 5100 Social Science Plaza, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA 92697-5100, U.S.A., E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] 1 Contents 1 Introduction3 2 Arithmetical comprehension and related systems5 2.1 Russell, Poincar´e,Zermelo, and Weyl on set existence . .5 2.2 Grzegorczyk, Mostowski, and Kond^oon effective analysis . .7 2.3 Kreisel on predicative definability . .9 2.4 Kreisel, Wang, and Feferman on predicative provability . 10 2.5 ACA0 as a formal system . 11 3 Hilbert and Bernays, the Grundlagen der Mathematik, and recursive com- prehension 13 3.1 From the Axiom of Reducibility to second-order arithmetic . -

Professor Errett Bishop Memorial

Professor Errett Bishop memorial September 15, 1983 A memorial meeting honoring the late Professor Errett Bishop and sponsored by the Department of Mathematics at the University of California, San Diego will be held on the campus Saturday, September 24. The meeting, scheduled to begin at 9 a.m., will be held in Sumner Auditorium at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Dr. Bishop served as a professor of mathematics at UCSD for 18 years and was considered one of the nation's most eminent mathematicians. He died April 14 in his home in La Jolla after a brief illness. A highlight of the day-long meeting will be the announcement of the establishment of the Errett Bishop Scholarship in Mathematics funded by a personal gift of $50,000 from Mrs. Helen Bishop of La Jolla, Professor Bishop's mother. The money will be placed into an endowment with the annual earnings to be used as an undergraduate scholarship in the field of mathematics. The annual grants will be made on the basis of proven scholarship and financial need with the intent that any outstanding student be assured of completing his or her undergraduate education regardless of financial need. A number of Professor Bishop's former colleagues have been invited from throughout the United States to discuss the impact of his work. They include Dr. Stefan Warschawski, professor of mathematics emeritus at UCSD, Dr. John Wermer from Brown University, Dr. John Kelley from UC Berkeley, Dr. Halsey Royden from Stanford University, Dr. Irving Glicksberg from the University of Washington and Dr. Gabriel Stolzenberg from Northeastern University.