Future of Imagination 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance Art

(hard cover) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Master of Arts Fine Arts 2006 LASALLE-SIA COLLEGE OF THE ARTS (blank page) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts) LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts Faculty of Fine Arts Singapore May, 2006 ii Accepted by the Faculty of Fine Arts, LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts). Vincent Leow Studio Supervisor Adeline Kueh Thesis Supervisor I certify that the thesis being submitted for examination is my own account of my own research, which has been conducted ethically. The data and the results presented are the genuine data and results actually obtained by me during the conduct of the research. Where I have drawn on the work, ideas and results of others this has been appropriately acknowledged in the thesis. The greater portion of the work described in the thesis has been undertaken subsequently to my registration for the degree for which I am submitting this document. Lee Wen In submitting this thesis to LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations and policies of the college. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the work may be made available and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. This work is also subject to the college policy on intellectual property. -

Exhibition Guide

ArTScience MuSeuM™ PreSenTS ceLeBrATinG SinGAPOre’S cOnTeMPOrArY ArT Exhibition GuidE Detail, And We Were Like Those Who Dreamed, Donna Ong Open 10am to 7pm daily | www.MarinaBaySands.com/ArtScienceMuseum Facebook.com/ArtScienceMuseum | Twitter.com/ArtSciMuseum WELCOME TO PRUDENTIAL SINGAPORE EYE Angela Chong Angela chong is an installation artist who Prudential Singapore Eye presents a with great conceptual confidence. uses light, sound, narrative and interactive comprehensive survey of Singapore’s Works range across media including media to blur the line between fiction and contemporary art scene through the painting, installation and photography. reality. She has shown work in Amsterdam Light Festival in the netherlands; Vivid works of some of the country’s most The line-up includes a number of Festival in Sydney; 100 Points of Light Festival innovative artists. The exhibiting artists who are gaining an international in Melbourne; cP international Biennale in artists were chosen from over 110 following, to artists who are just Jakarta, indonesia, and iLight Marina Bay in submissions and represent a selection beginning to be known. Like all the other Singapore. of the best contemporary art in Prudential Eye exhibitions, Prudential 3D Tic-Tac-Toe is an interactive light sculpture Singapore. Prudential Singapore Eye is Singapore Eye aims to bring to light which allows multiple players of all ages to the first major exhibition in a year of a new and exciting contemporary art play Tic-Tac-Toe with one another. cultural celebrations of the nation’s 50th scene and foster greater appreciation of anniversary. Singapore’s visual art scene both locally and internationally. 3D Tic-Tac-Toe, 2014 The works of the exhibiting artists demonstrate versatility, with many of the artists working experimentally Jeremy Sharma Jeremy Sharma works primarily as a conceptual painter. -

Singapore Biennale 2019: Every Step in The

Media Release Singapore Biennale 2019: Every Step In The Right Direction Opens Across Multiple Sites in Singapore on 22 November 2019 77 artists and collectives reflect on contemporary life and the human endeavour for change 20 Nov 2019 - Singapore Biennale 2019 (SB2019) returns for its sixth edition, with 77 artists and art collectives from 36 countries and territories. Titled Every Step in the Right Direction, the international contemporary art exhibition invites the public to engage with the act of artistic exploration, drawing on the importance of making choices and taking steps to consider the conditions of contemporary life and the human endeavour for change. Commissioned by the National Arts Council and organised by SAM, the Singapore Biennale will run from 22 November 2019 until 22 March 2020 across 11 venues in the city. With a strong focus on Southeast Asia, the sixth edition welcomes over 150 works across a breadth of diverse mediums including film, installation, sound art and performance, as well as new commissions and works that have never been presented in contemporary art biennales and exhibitions internationally. SB2019’s opening weekend will feature programmes for the public, including artist performances, curator and artist tours and talks. Organised by Singapore Art Museum | Commissioned by National Arts Council, Singapore Supported by the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth 61 Stamford Road, #02-02, Stamford Court, Singapore 178892 . www.singaporeartmuseum.sg 1 Singapore Biennale 2019: Every Step in the Right Direction refers to the ethical imperative for both artists and audiences to make choices and take steps to reflect on the conditions of contemporary life. -

Art of Tang Da Wu

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Body and communication : the ‘ordinary’ art of Tang Da Wu Wee, C. J. Wan‑Ling 2018 Wee, C. J. W.‑L. (2018). Body and communication : the ‘ordinary’ artof Tang Da Wu. Theatre Research International, 42(3), 286‑306. doi:10.1017/S0307883317000591 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/144518 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0307883317000591 © 2018 International Federation for Theatre Research. All rights reserved. This paper was published by Cambridge University Press in Theatre Research International and is made available with permission of International Federation for Theatre Research. Downloaded on 27 Sep 2021 10:02:22 SGT Accepted and finalized version of: Wee, C. J. W.-L. (2018). ‘Body and communication: The “Ordinary” Art of Tang Da Wu’. Theatre Research International, 42(3), 286-306. C. J. W.-L. Wee [email protected] Body and Communication: The ‘Ordinary’ Art of Tang Da Wu Abstract What might the contemporary performing body look like when it seeks to communicate and to cultivate the need to live well within the natural environment, whether the context of that living well is framed and set upon either by longstanding cultural traditions or by diverse modernizing forces over some time? The Singapore performance and visual artist Tang Da Wu has engaged with a present and a region fractured by the predations of unacceptable cultural norms – the consequences of colonial modernity or the modern nation-state taking on imperial pretensions – and the subsumption of Singapore society under capitalist modernization. Tang’s performing body both refuses the diminution of time to the present, as is the wont of the forces he engages with, and undertakes interventions by sometimes elusive and ironic means – unlike some overdetermined contemporary performance art – that reject the image of the modernist ‘artist as hero’. -

Lee Wen Strange Fruit 2003 C-Print Photographs, Set of 12, Edition 1/3 + 2 A.P

Learning Gallery Lesson Resources Lee Wen Strange Fruit 2003 C-Print photographs, set of 12, edition 1/3 + 2 A.P. 42 x 59.4 cm (each) Singapore Art Museum collection Exhibition Guide: page 12 – 13 © Singapore Art Museum, All rights reserved. No part of this resource may be reproduced without prior permission from the Singapore Art Museum Learning Gallery Lesson Resources Pre-SAM TASK: Think about how objects can be signifiers of cultural identity and place. SUBJECT(S): Literature, Cultural Heritage READ Have students analyse the poem, Postcards from Chinatown by Terrence Heng. From the poem, come up with a list of objects that are signifiers of the Chinese identity. Guiding questions for poem analysis: What kind of mood/atmosphere is conveyed through the poet’s description of Chinatown? What do you think the poet feels about the changes Chinatown is undergoing? CONNECT If possible, have the students explore Chinatown. Let them compare their own experience with that of the poet’s. Examples they can think about include: Objects Scenes of daily life Smells Sounds Alternatively, compare Singapore’s Chinatown and the Chinatowns in other countries such as America, United Kingdom, Australia, etc. © Singapore Art Museum, All rights reserved. No part of this resource may be reproduced without prior permission from the Singapore Art Museum Learning Gallery Lesson Resources In-SAM TASK: Transmediate understanding of artwork through creative writing and performance. SUBJECT(S): Art, Literature, Drama, Cultural Heritage DISCUSS Have students observe Lee Wen’s Strange Fruit silently for 1 minute. Next, get them to sit in front of the artwork and discuss the following questions: What is the cultural and symbolic use of lanterns during mid-autumn festival? Lee Wen has obscured his upper body with a cluster of red lanterns. -

World, the Interdisciplinary Arts and the Community: an Interview with the Artistic Director of the Substation – a Home for the Arts

The ‘Real’ World, the Interdisciplinary Arts and the Community: An Interview with the Artistic Director of The Substation – A Home for the Arts Noor Effendy Ibrahim, interviewed by C. J. W.-L. Wee What would you say are the present central goals of the historically first independent Singapore art centre, The Substation – A Home for the Arts? I have been Artistic Director of The Substation since February 2010. The key goal is clear: to continue and develop the legacy of this centre1 through artistic strategies and methods that are sensitive to and aware of the current and immediate cultural, political and economic contexts that exist. The Substation aims to provide a rigorous and safe space for the development and research into art practices that have a primarily interdisciplinary orientation – in short, the aim is to be a venue where dialogues occur and artistic curation and creation can transpire. It is apparent, though, that the physical infrastructure of The Substation is ageing, and that sufficient funding is also another key concern. So, a major issue is the re-thinking of how to make the available resources within The Substation itself good enough such that challenging artwork is possible, and so that the imagination of the larger arts community – the larger public, government agencies and possible funders – can be fired up to comprehend our commitment to interdisciplinary arts creation at The Substation, whatever the limitations and constraints of the moment. A particular challenge that we are face today lies in the education, the nurturing and the sustaining of critically informed and engaged audiences who will not be fearful of the artistic experimentation and exploration that form the backbone of interdisciplinary practice. -

The Next Gen Art Collectors 2021

COLLECTORS 1 THE NEXT COLLECTORS REPORT 2021 3 LARRY’S LIST is pleased to present The Next Gen that have not yet been acknowledged or made visible For us, size wasn’t a main consideration. Indeed, not a blue-chip artist will most likely generate more “likes” FOREWORDArt Collectors Report. Here, we continue our mission on a global scale. We want to share their stories and everyone listed has a large collection; charmingly, the than an unknown artist in an equally brilliant interior of monitoring global happenings, developments and thoughts. Next Gen often have collections in the making. The setting. But we still try to balance it and set aside any trends in the art world—particularly in the contemporary We also consider LARRY’S LIST as a guide and tool process is a development that happens over years care about the algorithm. art collector field—by looking extensively at the next for practitioners. We share and name collectors, those and so a mid-20-year-old collector may not yet be at generation of young art collectors on the scene. Over people who are buying art and contributing to the the same stage in their collection as someone in their Final words the past few months, we have investigated and profiled art scene. The Next Gen Art Collectors Report is a late 30s. I would like to express my gratitude to all the collectors these collectors, answering the questions central to this resource for artists, galleries, dealers, a general art- The end result of our efforts is this report listing over we exchanged with in the preparation of this report topic: Who are these collectors founding the next art interested audience and, of course, peer collectors. -

TK Sabapathy, Writing the Modern: Selected Texts on Art & Art History

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Singapore Art Museum publishes four decades of critical and historical texts by renowned art scholar, critic and curator T.K. Sabapathy T.K Sabapathy, Writing the Modern: Selected Texts on Art & Art History in Singapore, Malaysia & Southeast Asia, 1973-2015. Edited by Ahmad Mashadi, Susie Lingham, Peter Schoppert and Joyce Toh, Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2018. SINGAPORE, 22 JANUARY 2018 – During Singapore Art Week 2018, Singapore Art Museum (SAM) will launch an anthology of texts by esteemed art critic, curator and scholar of art developments and art history in Singapore, Malaysia and Southeast Asia from the 1970s to 2010s, T.K. Sabapathy. Selected from over four decades of critical and historical scholarship, Writing the Modern: Selected Texts on Art & Art History in Singapore, Malaysia & Southeast Asia, 1973-2015 brings together Sabapathy’s most significant and influential writings for the first time. With its detailed explication of artworks and critical reflections on art historical developments in Singapore, Malaysia and Southeast Asia, the anthology will serve as maps for an exploration of visual art development and art histories of the region. From the early 1970s, through SAM’s founding in 1996, and till today, T.K. Sabapathy has contributed significantly to Singapore’s and the regional art scene in various capacities – as historian and educator, critic, advisor and advocate of the visual arts and culture. His dedication to the documentation and development of the region’s art scene has been instrumental in the building of the modern and contemporary art history of Singapore and Southeast Asia, and in the establishment of SAM. -

A Performing Archive 17.02.17, 10�14

re.act.feminism - a performing archive 17.02.17, 1014 Search A Ebtisam Abdulaziz Marina Abramović Helena Almeida Eleanor Antin Arahmaiani Malin Arnell Oreet Ashery Augusta Atla Margarita Azurdia B Back to selection Antonia Baehr Complete Archive Maja Bajević Manon, La dame au crâne rasé, 1970s Anne Bean Anat Ben-David Renate Bertlmann Manon Document media Pauline Boudry & Das lachsfarbene Boudoir / La dame au crâne video, colour, sound, 12:10 min Renate Lorenz rasé Issue date Nisrine Boukhari 1974, 1978 / 2006 After studying commercial art and acting in Zurich, in 1974 Marijs Boulogne Tags Manon (*1946, Switzerland) began creating environments in Tania Bruguera beauty, fashion/glamour, which she plays different roles together with sometimes as femininity, in/visibility, Nancy Buchanan many as 60 extras and uses virtually all forms of modern private/public Maris Bustamante media. She was one of Switzerland’s first performance artists About the project C Archive Signature Partners and is most likely the country’s most famous. She lived in Paris MAN 1 Cabello / Carceller Imprint from 1977 to 1980 before moving back to Zurich, where she lives Shirley Cameron/ Contact and works today. Since 1998, she has been concentrating Monica Ross/ Find us on facebook mainly on installations which explore eroticism and transience, Evelyn Silver most recently in 2011 in her project "Hotel Dolores" concerned Graciela Carnevale with deserted spa hotels in the spa district of Baden, Aargau Theresa Hak Kyung (Switzerland). Cha Helen Chadwick This is a collection of TV features about, among other works, Manon’s Das lachsfarbene Boudoir (The Salmon-Coloured Chicks on Speed Boudoir), her first environment which she reconstructed for the Lygia Clark Migros Museum Zurich in 2006, and La dame au crâne rasé (The Mary Coble Woman with the Shaved Head), a series of staged photographs Colette in Paris. -

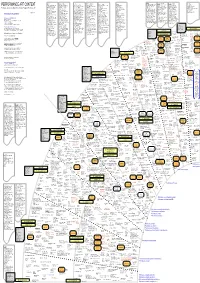

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

Singapore Art Museum Announces the Singapore

MEDIA ALERT SINGAPORE ART MUSEUM ANNOUNCES THE SINGAPORE BIENNALE 2019 FINAL ARTIST LIST AND COORDINATES PROJECTS Over 70 artists and art collectives from around the world will be presented SINGAPORE – 24 OCTOBER 2019 – The Singapore Art Museum (SAM) is pleased to announce the artist list for the Singapore Biennale 2019 (SB2019). With over 70 artists and art collectives from around the world and a strong focus on Southeast Asia, the 6th edition welcomes over 150 works across a breadth of diverse mediums including film, installation, sound art and performance. Complementing the Singapore Biennale will be the Coordinates Projects - seven ground up initiatives and organisations that will present a suite of exhibitions, community programmes, workshops and tours. These projects will expand upon this Biennale’s theme, Every Step in the Right Direction. Commissioned by the National Arts Council and organised by SAM, the Singapore Biennale will run from 22 November 2019 until 22 March 2020 in multiple nodes across 11 venues in the city. Early bird tickets will be available for purchase online and at SISTIC counters from 22 October 2019. SB2019 PARTICIPATING ARTISTS In addition to the artists announced earlier, SB2019 will include: Larry Achiampong (United Kingdom), Laurie Anderson (USA) & Hsin-Chien Huang (Taiwan), C&G (Hong Kong), Centro Audiovisual Max Stahl Timor-Leste (CAMSTL) (Timor-Leste), Desire Machine Collective (India), Korakrit Arunanondchai (Thailand / USA), Lawrence Lek (UK), muf architecture/art (UK), Judy Freya Sibayan (The Philippines), The Mamitua Saber Project with Bakudapan Food Study Group (Indonesia), •• PROPAGANDA DEPARTMENT (Hong Kong / China) and Mark Sanchez (The Philippines), and Jason Wee (Singapore). -

Annual Report 2018–19 Snapshot of the National Gallery of Australia

Annual Report 2018–19 Snapshot of the National Gallery of Australia Who we are What we do The National Gallery of Australia The Gallery provides opened to the public in October 1982 exceptional experiences of and is the Commonwealth of Australia’s rich visual arts Australia’s national cultural institution for the culture. Through the national collection, visual arts. Since it was established in 1967, it exhibitions, educational and public programs, has played a leadership role in shaping visual outreach initiatives, research and publications, arts culture across Australia and its region and infrastructure and corporate services, the continues to develop exciting and innovative Gallery is a model of excellence in furthering ways to engage people with the national knowledge of the visual arts. The Gallery art collection. makes art accessible, meaningful and vital to diverse audiences, locally, nationally and internationally. Our purpose and outcome Our staff As Australia’s pre-eminent visual staff at 30 June 2019. The Gallery arts institution, the Gallery provides 326 has an inclusive workforce, social and cultural benefits for the employing people with a disability and people community and enhances Australia’s with culturally diverse backgrounds, including international reputation. The Gallery’s one Indigenous Australians. Women represent outcome, as outlined in the Portfolio Budget 67% of the Gallery’s workforce and 50% Statements 2018–19, is ‘Increased of its Senior Management Group. Detailed understanding, knowledge and enjoyment staffing information is on pages 72–7. of the visual arts by providing access to, and information about, works of art locally, nationally and internationally’. Our collection Our supporters Over nearly half a century of The Gallery nurtures strong collecting, the Gallery has achieved relationships with external extraordinary outcomes in acquiring stakeholders, such as artists and and displaying Australian and international art.