Otpor's Usage of Nonviolent Action to Undermine the Authority Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CDDRL Number 114 WORKING PAPERS June 2009

CDDRL Number 114 WORKING PAPERS June 2009 Youth Movements in Post- Communist Societies: A Model of Nonviolent Resistance Olena Nikolayenko Stanford University Center on Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Additional working papers appear on CDDRL’s website: http://cddrl.stanford.edu. Center on Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Stanford University Encina Hall Stanford, CA 94305 Phone: 650-724-7197 Fax: 650-724-2996 http://cddrl.stanford.edu/ About the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL) CDDRL was founded by a generous grant from the Bill and Flora Hewlett Foundation in October in 2002 as part of the Stanford Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. The Center supports analytic studies, policy relevant research, training and outreach activities to assist developing countries in the design and implementation of policies to foster growth, democracy, and the rule of law. About the Author Olena Nikolayenko (Ph.D. Toronto) is a Visiting Postdoctoral Scholar and a recipient of the 2007-2009 post-doctoral fellowship from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Her research interests include comparative democratization, public opinion, social movements, youth, and corruption. In her dissertation, she analyzed political support among the first post-Soviet generation grown up without any direct experience with communism in Russia and Ukraine. Her current research examines why some youth movements are more successful than others in applying methods of nonviolent resistance to mobilize the population in non-democracies. She has recently conducted fieldwork in Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Serbia, and Ukraine. -

Revolutionary Tactics: Insights from Police and Justice Reform in Georgia

TRANSITIONS FORUM | CASE STUDY | JUNE 2014 Revolutionary Tactics: Insights from Police and Justice Reform in Georgia by Peter Pomerantsev with Geoffrey Robertson, Jovan Ratković and Anne Applebaum www.li.com www.prosperity.com ABOUT THE LEGATUM INSTITUTE Based in London, the Legatum Institute (LI) is an independent non-partisan public policy organisation whose research, publications, and programmes advance ideas and policies in support of free and prosperous societies around the world. LI’s signature annual publication is the Legatum Prosperity Index™, a unique global assessment of national prosperity based on both wealth and wellbeing. LI is the co-publisher of Democracy Lab, a journalistic joint-venture with Foreign Policy Magazine dedicated to covering political and economic transitions around the world. www.li.com www.prosperity.com http://democracylab.foreignpolicy.com TRANSITIONS FORUM CONTENTS Introduction 3 Background 4 Tactics for Revolutionary Change: Police Reform 6 Jovan Ratković: A Serbian Perspective on Georgia’s Police Reforms Justice: A Botched Reform? 10 Jovan Ratković: The Serbian Experience of Justice Reform Geoffrey Robertson: Judicial Reform The Downsides of Revolutionary Maximalism 13 1 Truth and Reconciliation Jovan Ratković: How Serbia Has Been Coming to Terms with the Past Geoffrey Robertson: Dealing with the Past 2 The Need to Foster an Opposition Jovan Ratković: The Serbian Experience of Fostering a Healthy Opposition Russia and the West: Geopolitical Direction and Domestic Reforms 18 What Georgia Means: for Ukraine and Beyond 20 References 21 About the Author and Contributors 24 About the Legatum Institute inside front cover Legatum Prosperity IndexTM Country Factsheet 2013 25 TRANSITIONS forum | 2 TRANSITIONS FORUM The reforms carried out in Georgia after the Rose Revolution of 2004 were Introduction among the most radical ever attempted in the post-Soviet world, and probably the most controversial. -

Oslo Scholars Program 2020

OSLO SCHOLARS PROGRAM 2020 The Oslo Scholars Program offers undergraduates with a demonstrated interest in human rights and international political issues an opportunity to attend the Oslo Freedom Forum and to spend their summer interning with some of the world’s leading human rights defenders and activists. Applications are due March 13, 2020 at 11:59pm SUMMER 2020 INTERNSHIPS Srdja Popovic (CANVAS) Srdja Popovic is a founding member of Otpor! the Serbian civic youth movement that played a pivotal role in the ousting of Slobodan Milosevic. He is a prominent nonviolent expert and the leader of CANVAS, a nonprofit organization dedicated to working with nonviolent democratic movements around the world. CANVAS works with citizens from more than 30 countries, sharing nonviolent strategies and tactics that were used by Otpor!. A native of Belgrade, Popovic has promoted the principles and strategies of nonviolence as tools for building democracy since helping to found the Otpor! movement. Otpor! began in 1998 as a university- based organization; after only two years, it quickly grew into a national movement, attracting more than 70,000 supporters. A student of nonviolent strategy, Popovic translated several works on the subject, such as the books of American scholar Gene Sharp, for distribution. He also authored “Blueprint for Revolution”, a handbook for peaceful protesters, activists, and community organizers. After the overthrow of Milosevic, Popovic served in the Serbian National Assembly from 2000 to 2003. He served as an environmental affairs advisor to the prime minister. He left the parliament in 2003 to start CANVAS. The organization has worked with people in 46 countries to transfer knowledge of effective nonviolent tactics and strategies. -

Nonviolent Struggle : 50 Crucial Points : a Strategic Approach to Everyday Tactics / Srdja Popovic, Andrej Milivojeic, Slobodan Djinovic ; [Comments by Robert L

NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE 50 crucial points CANVAS Center for Applied NonViolent Action and Strategies NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE 50 CRUCIAL POINTS NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE 50 CRUCIAL POINTS A strategic approacH TO EVERYDAY tactics Srdja Popovic • Andrej Milivojevic • Slobodan Djinovic CANVAS Centre for Applied NonViolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS) Belgrade 2006. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: How to read this book? . 10 This publication was prepared pursuant to the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) Grant USIP-123-04F, I Before You Start . 12 April 1, 2005. Chapter 1. Introduction to Strategic Nonviolent Conflict . 14 First published in Serbia in 2006 by Srdja Popovic, Andrej Milivojevic and Slobodan Djinovic Chapter 2. The Nature, Models and Sources of Political Power . 24 Copyright © 2006 by Srdja Popovic, Andrej Milivojevic Chapter 3. Pillars of Support: How Power is Expressed . 32 and Slobodan Djinovic All rights reserved. II Starting Out . .38 The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommen- dations expressed in this publication are those of the Chapter 4. Assessing Capabilities and Planning . 42 author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Chapter 5. Planning Skills: The Plan Format . 50 United States Institute of Peace. Chapter 6. Targeted Communication: Message Development . 58 Graphic design by Ana Djordjevic Chapter . Let the World Know Your Message: Comments by Robert L. Helvey and Hardy Merriman Photo on cover by Igor Jeremic Performing Public Actions . 66 III Running a Nonviolent Campaign . 2 Printed by Cicero, Belgrade 500 copies, first edition, 2006. Chapter 8. Building a Strategy: From Actions to Campaigns . 6 Produced and printed in Serbia Chapter 9. Managing a Nonviolent Campaign: Material Resources . -

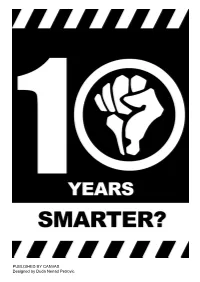

Chronology of Events – a Brief History of Otpor PUBLISHED by CANVAS

Chronology of Events – A Brief History of Otpor PUBLISHED BY CANVAS Designed by Duda Nenad Petrovic RESISTANCE! Chronology of Events – A Brief History of Otpor Chronology of Events – A Brief History of Otpor May 26, 1998 – University Act passed. November 4, 1998 – The concert organized by the ANEM (Association of Independent Electronic Media) under the October 20, 1998 – Media Act passed. slogan “It’s not like Serbs to be quiet” was held. Otpor ac- tivists launched a seven-day action “Resistance is the an- End of October 1998 – In response to the new Univer- swer”, within which they distributed flyers with provocative sity Act and Media Act, which were contrary to students’ questions relating to endless resignation and suffering of interests, the Student Movement Otpor was formed. all that we had been going through and slogans such as Among Otpor’s founders were Srdja Popovic, Slobodan “Bite the system, live the resistance”. Homen, Slobodan Djinovic, Nenad Konstantinovic, Vu- kasin Petrovic, Ivan Andric, Jovan Ratkovic, Andreja Sta- menokovic, Dejan Randjic, Ivan Marovic. The group was soon joined by Milja Jovanovic, Branko Ilic, Pedja Lecic, Sinisa Sikman, Vlada Pavlov from Novi Sad, Stanko La- zentic, Milan Gagic, Jelena Urosevic and Zoran Matovic from Kragujevac and Srdjan Milivojevic from Krusevac. In the beginning, among the core creators of Otpor were Bo- ris Karaicic, Miodrag Gavrilovic, Miroslav Hristodulo, Ras- tko Sejic, Aleksa Grgurevic and Aleksandar Topalovic, but they left the organization later. During this period, Nenad Petrovic, nicknamed Duda, a Belgrade-based designer, designed the symbol of Otpor – a clenched fist. In the night between November 2 and 3, 1998, four students were arrested for spraying the fist and slogans “Death to fascism” and “Resistance for freedom”: Teodo- ra Tabacki, Marina Glisic, Dragana Milinkovic and Nikola Vasiljevic. -

Otpor and the Struggle for Democracy in Serbia

Otpor and the Struggle for Democracy in Serbia (1998-2000) Dr. Lester R. Kurtz Professor of Sociology / Anthropology, George Mason February 2010 Summary of events related to the use or impact of civil resistance ©2010 International Center on Nonviolent Conflict Disclaimer: Hundreds of past and present cases of nonviolent civil resistance exist. To make these cases more accessible, the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict (ICNC) compiled summaries of some of them between the years 2009-2011. Each summary aims to provide a clear perspective on the role that nonviolent civil resistance has played or is playing in a particular case. The following is authored by someone who has expertise in this particular region of the world and/or expertise in the field of civil resistance. The author speaks with his/her own voice, so the conflict summary below does not necessarily reflect the views of ICNC. Additional ICNC Resources: For additional resources on civil resistance, see ICNC's Resource Library, which features resources on civil resistance in English and over 65 other languages. To support scholars and educators who are designing curricula and teaching this subject, we also offer an Academic Online Curriculum (AOC), which is a free, extensive, and regularly updated online resource with over 40 different modules on civil resistance topics and case studies. To read other nonviolent conflict summaries, visit ICNC’s website: http://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/ Click here to access the ICNC website. Click here to access more civil resistance resources in English through the ICNC Resource Library. Click here to access the ICNC Films Library to see films on civil resistance in English. -

The Serbian Paradox: the Cost of Integration Into the European Union

The Serbian Paradox: The Cost of Integration into the European Union Preston Huennekens Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Political Science Yannis A. Stivachtis, Chair Besnik Pula Glenn R. Bugh April 17, 2018 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: Serbia, European Union, historical memory, nationalism, Balkan politics The Serbian Paradox: The Cost of Integration into the European Union Preston Huennekens Abstract This project addresses the Republic of Serbia’s current accession negotiations with the European Union, and asks how the country’s long and often turbulent history affects that dialogue. Using Filip Ejdus’ concept of historical memory and Benedict Anderson’s “imagined community” theory of nationalism, this paper discusses how Serbia has reached a critical moment in its history by pursuing European integration. This contradicts their historical pull towards their longtime ally Russia. What role does historical memory play in these negotiations, and is integration truly possible? Additionally, how is Serbia’s powerful president, Aleksandar Vucic, using the Europeanization process to strengthen his hand domestically? Abstract (General Audience) This thesis addresses the Republic of Serbia’s current accession negotiations with the European Union, and asks how the country’s long and often turbulent history affects that dialogue. I argue that Serbia is at a crossroads in its history: on one hand, it wishes to join the European Union, but on the other is continually pulled to the east with their historical ally, Russia. I argue that President Aleksandar Vucic is using the EU negotiations to enhance his own power and that if the EU admits Serbia into the body they will be trading regional stability for Serbian democracy. -

On Strategic Nonviolent Conflict

ON STRATEGIC NONVIOLENT CONFLICT: THINKING ABOUT THE FUNDAMENTALS ON STRATEGIC NONVIOLENT CONFLICT: THINKING ABOUT THE FUNDAMENTALS Robert L. Helvey The Albert Einstein Institution Copyright © 2004 by Robert Helvey All rights reserved including translation rights. Printed in the United States of America. First Edition, July 2004 Printed on recycled paper. This publication was prepared pursuant to the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) Grant SG-127-02S, September 19, 2002 This publication has been printed with the assistance of the Connie Grice Memorial Fund. Connie Grice was Executive Director of the Albert Einstein Institution, 1986-1988. With her experience in the civil rights movement and deep commitment to a peaceful and just world, she played a crucial role in the early years of the Institution. Although her life was cut too short, we who worked with her know that she would have been very happy that her memory could continue to support the work of this Institution. The Connie Grice Fund was established by her husband William Spencer and her sister Martha Grice. The Albert Einstein Institution 427 Newbury Street Boston, MA 02115-1801, USA Tel: USA + 617-247-4882 Fax: USA + 617-247-4035 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.aeinstein.org ISBN 1-880813-14-9 “All men dream: but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds wake in the day to find it was vanity, but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act on their dream with open eyes, to make it possible.” T. -

The Role of Power in Nonviolent Struggle the Role of Power in Nonviolent Struggle

The Role of Power in Nonviolent Struggle The Role of Power in Nonviolent Struggle Gene Sharp Monograph Series Number 3 The Albert Einstein Institution Copyright 01990 by Gene Sharp First Printing, October 1990 Second Printing, August 1994 Third Printing, September 2000 This paper was originally delivered at the Conference on Nonviolent Political Struggle, sponsored by the ArabThought Forum, Amman, Jordan, November 15-17,1986. It has been published in Arabic and Burmese, and is pending publica- tion in Chinese. This essay is also published in Ralph E. Crow, Philip Grant, and Saad E. Ibrahim, editors, Arab Nonviolent Political Struggle in the Middle East. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1990. Printed in the United States of America. Printed on Recycled Paper. The Albert Einstein Institution 427 Newbury Street Boston, MA 02115-1801 USA ISSN 1052-1054 ISBN 1-880813-02-5 by Gene Sharp Introduction Nonviolent struggle is based upon the very nature of power in society and politics. The practice, dynamics, and consequences of nonviolent struggle are all directly dependent upon the wielding of power and its effectson the power of the opponent group. This technique cannot be understood without consideration of this important element in its nature. This perception is in direct contradiction to the popular miscon- ceptions that nonviolent action is powerless, that it conceptually and politically ignores the reality of power in politics, and that its advo- cates are naive in not accepting that violence is the real source of power in politics. These misconceptions, however, are themselves rooted in a denial or ignoring of the nature of power in politics and the crucial role of power in the operation of nonviolent struggle. -

1 a Blueprint for Climate Revolution Srdja Popovic Serbia

A Blueprint for Climate Revolution Srdja Popovic Serbia Like many young men, Srdja Popovic had a quite singular mind in his early twenties. He didn’t see himself as a revolutionary. Quite the contrary — what he most wanted to do was go to parties and play punk music. “At that age I was more into dating girls and playing in a rock band,” he says. “I was thinking that basically activism is for old ladies who were fighting for dogs’ rights.” Srdja played bass in the goth punk band BAAL, which was an up-and-coming name in the Eastern European music scene. He studied biology at the University of Belgrade, and — as mentioned — liked to chase after girls from time to time. He was, in many senses, a pretty typical youth. But as fate would have it, he would not be able to live this life for long. In the early 1990s, in his native Serbia, the political situation began to deteriorate. The country’s president, Slobodan Milošević, was ruling with an increasingly iron fist. Milošević, who became known as the “Butcher of the Balkans,” repressed student protesters, detained and jailed activists, and stole elections. He left little room for dissent; the result was a culture of fear spread far and wide across the country. Seeing Milošević’s power grow, Srdja and thousands of other young people were confronted with a harsh political reality — and a tough choice. Suddenly it didn’t seem to Srdja that punk rock was the best use of his energy; nonviolent organizing to overthrow the regime was more important. -

Orange-Revolution-Study-Guide-2.Pdf

Study Guide Credits A Force More Powerful Films presents Produced and Directed by STEVE YORK Executive Producer PETER ACKERMAN Edited by JOSEPH WIEDENMAYER Managing Producer MIRIAM ZIMMERMAN Original Photography ALEXANDRE KVATASHIDZE PETER PEARCE Associate Producers SOMMER MATHIS NATALIYA MAZUR Produced by YORK ZIMMERMAN Inc. www.OrangeRevolutionMovie.com DVDs for home viewing are DVDs for educational use must available from be purchased from OrangeRevolutionMovie.coM The CineMa Guild and 115 West 30th Street, Suite 800 AForceMorePowerful.org New York, NY 10001 Phone: (800) 723‐5522 Also sold on Amazon.com Fax: (212) 685‐4717 eMail: [email protected] http://www.cineMaguild.coM Study Guide produced by York ZiMMerMan Inc. www.yorkziM.coM in association with the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict www.nonviolent‐conflict.org Writers: Steve York, Hardy MerriMan MiriaM ZiMMerMan & Cynthia Boaz Layout & Design: Bill Johnson © 2010 York ZiMMerMan Inc. Table of Contents An Election Provides the Spark ......................... 2 A Planned Spontaneous Revolution ................. 4 Major Characters .............................................. 6 Other Players .................................................... 7 Ukraine Then and Now ..................................... 8 Ukraine Historical Timeline ............................... 9 Not the First Time (Or the Last) ....................... 10 Epilogue ........................................................... 11 Additional Resources ....................................... 12 Questions -

The Milosevic Regime Versus Serbian Democracy and Balkan Stability

THE MILOSEVIC REGIME VERSUS SERBIAN DEMOCRACY AND BALKAN STABILITY HEARING BEFORE THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION DECEMBER 10, 1998 Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe [CSCE 105-2-?] Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.csce.gov COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS HOUSE SENATE CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ALFONSE M. DAMATO, New York, Chairman Chairman JOHN EDWARD PORTER, Illinois BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado FRANK R. WOLF, Virginia SPENCER ABRAHAM, Michigan MATT SALMON,Arizona CONRAD BURNS, Montana JON CHRISTENSEN, Nebraska OLYMPIA SNOWE, Maine STENY H. HOYER, Maryland FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts HARRY REID, Nevada BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland BOB GRAHAM, Florida LOUISE McINTOSH SLAUGHTER, New York RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS JOHN H.F. SHATTUCK, Department of State VACANT, Department of Defense VACANT, Department of Commerce COMMISSION S TAFF MIKE HATHAWAY, Chief of Staff DOROTHY DOUGLAS TAFT, Deputy Chief of Staff ELIZABETH CAMPBELL, Receptionist/System Administrator MARIA V. COLL, Office Administrator OREST DEYCHAKIWSKY, Staff Advisor JOHN FINERTY, Staff Advisor CHADWICK R. GORE, Communications Director, Digest Editor ROBERT HAND, Staff Advisor JANICE HELWIG, Staff Advisor MARLENE KAUFMANN, Counsel for International Trade SANDY LIST, GPO Liaison KAREN S. LORD,Counsel for Freedom of Religion RONALD MCNAMARA, Staff Advisor MICHAEL OCHS, Staff Advisor ERIKA B. SCHLAGER, Counsel for International Law MAUREEN WALSH, Congressional Fellow for Property Restitution Issues (ii) THE MILOSEVIC REGIME VERSUS SERBIAN DEMOCRACY AND BALKAN STABILITY DECEMBER 10, 1998 OPENING STATEMENTS PAGE Opening Statement of Co-Chairman Christopher H.