2004-05 Gaze PHD THESIS As in Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World Beautiful in Books TO

THE WORLD BEAUTIFUL IN BOOKS BY LILIAN WHITING Author of " The World Beautiful," in three volumes, First, Second, " " and Third Series ; After Her Death," From Dreamland Sent," " Kate Field, a Record," " Study of Elizabeth Barrett Browning," etc. If the crowns of the world were laid at my feet in exchange for my love of reading, 1 would spurn them all. — F^nblon BOSTON LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY ^901 PL Copyright, 1901, By Little, Brown, and Company. All rights reserved. I\17^ I S ^ November, 1901 UNIVERSITY PRESS JOHN WILSON AND SON • CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A. Lilian SMIjttins'fii glMoriiB The World Beautiful. First Series The World Beautiful. Second Series The World Beautiful. Third Series After her Death. The Story of a Summer From Dreamland Sent, and Other Poems A Studv of Elizabeth Barrett Browning The Spiritual Significance Kate Field: a Record The World Beautiful in Books TO One whose eye may fall upon these pages; whose presence in tlie world of thought and achievement enriches life ; whose genius and greatness of spirit inspire my every day with renewed energy and faith, — this quest for " The World Beautiful" in literature is inscribed by LILIAN WHITING. " The consecration and the poeVs dream" CONTENTS. BOOK I. p,,. As Food for Life 13 BOOK II. Opening Golden Doors 79 BOOK III. The Rose of Morning 137 BOOK IV. The Chariot of the Soul 227 BOOK V. The Witness of the Dawn 289 INDEX 395 ; TO THE READER. " Great the Master And sweet the Magic Moving to melody- Floated the Gleam." |0 the writer whose work has been en- riched by selection and quotation from " the best that is known and thought in* the world," it is a special pleasure to return the grateful acknowledgments due to the publishers of the choice literature over whose Elysian fields he has ranged. -

Lesbian and Gay Music

Revista Eletrônica de Musicologia Volume VII – Dezembro de 2002 Lesbian and Gay Music by Philip Brett and Elizabeth Wood the unexpurgated full-length original of the New Grove II article, edited by Carlos Palombini A record, in both historical documentation and biographical reclamation, of the struggles and sensi- bilities of homosexual people of the West that came out in their music, and of the [undoubted but unacknowledged] contribution of homosexual men and women to the music profession. In broader terms, a special perspective from which Western music of all kinds can be heard and critiqued. I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 II. (HOMO)SEXUALIT Y AND MUSICALIT Y 2 III. MUSIC AND THE LESBIAN AND GAY MOVEMENT 7 IV. MUSICAL THEATRE, JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSIC 10 V. MUSIC AND THE AIDS/HIV CRISIS 13 VI. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 1990S 14 VII. DIVAS AND DISCOS 16 VIII. ANTHROPOLOGY AND HISTORY 19 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 X. EDITOR’S NOTES 24 XI. DISCOGRAPHY 25 XII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 What Grove printed under ‘Gay and Lesbian Music’ was not entirely what we intended, from the title on. Since we were allotted only two 2500 words and wrote almost five times as much, we inevitably expected cuts. These came not as we feared in the more theoretical sections, but in certain other tar- geted areas: names, popular music, and the role of women. Though some living musicians were allowed in, all those thought to be uncomfortable about their sexual orientation’s being known were excised, beginning with Boulez. -

Katalog 152 Ohne Bilder.Pdf

MUSIKDRUCKE 1 Absil, Jean (1893-1974): 3e Quatuor à Cordes. Op. 19. Brüssel, Centre Belge de Documentation Musicale (o.V.Nr.) (1962). Stimmen: 15, 15, 15, 15 lithogr. S. Umschlag. €40,– Umschlag mit Randausbesserungen. 2 Achron, Joseph (1886-1943): Liebeswidmung - Souvenir D'Amour - Love-Offering... Op. 51. Violino e Piano. Wien, UE (V.Nr. 7585) [1924]. Stimmen: 3, 1 S. 4°. Umschlag. €35,– Erstausgabe. - Gelegentlich leicht stockfleckig. 3 Alard, Delphin (1815-1888): École du Violon. Méthode complète et progressive à l'usage du Conservatoire... à Sa Majeste Victor-Emmanuel, Roi d'Italie. Edition augmentée. Paris, Schonen- berger (Pl.Nrn. 1132, 2732) [ca. 1855]. 150 gest. S. Hldr.d.Zt. €75,– Titelauflage der zweiten, erweiterten Fassung dieses äußerst erfolgreichen, in mehrere Sprachen übersetzten Lehrwerks. - Einband berieben und bestoßen, Seiten vereinzelt finger- und stockfleckig. 4 d'Albert, Eugen (1864-1932): Erstes Konzert (H moll) in einem Satz, für Klavier und Orchester... Meinem hochverehrten Meister Dr. Franz Liszt in Dankbarkeit zugeeignet. Für Klavier zu vier Händen (Partitur-Ausgabe). Berlin, B&B (V.Nr. 12964) [ca. 1910]. 75 S. €70,– Titelauflage der Erstausgabe von 1885. - Sammeltitel mit Fotoportrait des Komponisten. - Um- schlagrücken verstärkt, Titelblatt mit Stempel und Randausbesserungen. 5 Altmann, Hans (1904-1961): Klaviersonate, A-dur op. 25. Klavier zweihändig. München, Edi- tion Kasparek (V.Nr. EKM 0106) [1948]. 23 S. €45,– Erstausgabe. - Rücken verstärkt, etwas knapp beschnitten (Umschlagornament und Verlagsnum- mern etwas angeschnitten). Seiten leicht vergilbt. 6 d'Alvimare, Martin Pierre (1772-1839): "Déjà". Chanson Avec Accompagnement de Forte Piano ou Harpe, Paroles de C.L.C... Paris, Corbaux [o.Pl.Nr.] [vor 1816]. -

Women, Gender, and Music During Wwii a Thesis

EDINBORO UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PITCHING PATRIARCHY: WOMEN, GENDER, AND MUSIC DURING WWII A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, POLITICS, LANGUAGES, AND CULTURES FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS SOCIAL SCIENCES-HISTORY BY SARAH N. GAUDIOSO EDINBORO, PENNSYLVANIA APRIL 2018 1 Pitching Patriarchy: Women, Music, and Gender During WWII by Sarah N. Gaudioso Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Master of Social Sciences in History ApprovedJjy: Chairperson, Thesis Committed Edinbqro University of Pennsylvania Committee Member Date / H Ij4 I tg Committee Member Date Formatted with the 8th Edition of Kate Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses and Dissertations. i S C ! *2— 1 Copyright © 2018 by Sarah N. Gaudioso All rights reserved ! 1 !l Contents INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: HISTORIOGRAPHY 5 CHAPTER 2: WOMEN IN MUSIC DURING WORLD WAR II 35 CHAPTER 3: AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN AND MUSIC DURING THE WAR.....84 CHAPTER 4: COMPOSERS 115 CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSIONS 123 BIBLIOGRAPHY 128 Gaudioso 1 INTRODUCTION A culture’s music reveals much about its values, and music in the World War II era was no different. It served to unite both military and civilian sectors in a time of total war. Annegret Fauser explains that music, “A medium both permeable and malleable was appropriated for numerous war related tasks.”1 When one realizes this principle, it becomes important to understand how music affected individual segments of American society. By examining women’s roles in the performance, dissemination, and consumption of music, this thesis attempts to position music as a tool in perpetuating the patriarchal gender relations in America during World War II. -

October 8, 2019 Elist MILLER

RULON~ October 8, 2019 eList MILLER BOOKS To Order: Call toll-free 1-800-441-0076 Outside the United States call 1-651-290-0700 400 Summit Avenue E-mail: [email protected] St. Paul, Minnesota Other catalogues available at our website at Rulon.com 55102-2662 USA Member ABAA/ILAB ~ R a r e & f i n e b o o k s VISA, MASTERCARD, DISCOVER, and AMERICAN EXPRESS accepted. If you have any questions regarding billing, methods of payment, in many fields shipping, or foreign currencies, please do not hesitate to ask. Manuscripts 1. Aesop. Fables of Aesop and other cution of Charles I, and in the midst of the eminent mythologists: with morals and controversy over the oath of loyalty demanded reflections. By Sir Roger L'Estrange, Kt. by the new republican government. Addresses London: printed for R. Sare, T. Sawbridge "Paying taxes," "Personall service," "Taking oaths," etc. Wing A3920. [et al.], 1692. $1,500 First L'Estrange edition, folio, pp. [10], 28, [8], 306, 319-480; gatherings S and T switched but the book is complete; this is a variant as noted by ESTC with p. 144 (first occurrence) misnum- bered 132; engraved portrait frontispiece of L'Estrange and plate of Aesop surrounded by animals; full speckled calf with a 20th-century rebacking, black morocco label on spine; light wear to boards, dampstain to upper right corner, very good. With the armorial bookplate of John Lord De La Warr. Wing A-706. 2. Ascham, Antony. A discourse wherein is examined, what is particularly lawfull during the confusions and revolu- tions of government. -

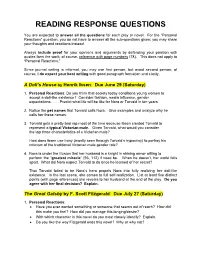

Reading Response Questions

READING RESPONSE QUESTIONS You are expected to answer all the questions for each play or novel. For the “Personal Reactions” question, you do not have to answer all the sub-questions given; you may share your thoughts and reactions instead. Always include proof for your opinions and arguments by defending your position with quotes form the work; of course, reference with page numbers (78). This does not apply to “Personal Reactions.” Since journal writing is informal, you may use first person, but avoid second person; of course, I do expect your best writing with good paragraph formation and clarity. A Doll’s House by Henrik IBsen: Due June 29 (Saturday) 1. Personal Reactions: Do you think that society today conditions young women to accept a doll-like existence? Consider fashion, media influence, gender expectations . Predict what life will be like for Nora or Torvald in ten years. 2. Notice the pet names that Torvald calls Nora. Give examples and analyze why he calls her these names. 3. Torvald gets a pretty bad rap most of the time because Ibsen created Torvald to represent a typical Victorian male. Given Torvald, what would you consider the top three characteristics of a Victorian male? How does Ibsen use irony (mostly seen through Torvald’s hypocrisy) to portray his criticism of the traditional Victorian male gender role? 4. Nora is under the illusion that her husband is a knight in shining armor willing to perform the “greatest miracle” (93, 112) if need be. When he doesn’t, her world falls apart. What did Nora expect Torvald to do once he learned of her secret? That Torvald failed to be Nora’s hero propels Nora into fully realizing her doll-like existence. -

The Pedagogical Legacy of Johann Nepomuk Hummel

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE PEDAGOGICAL LEGACY OF JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL. Jarl Olaf Hulbert, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Directed By: Professor Shelley G. Davis School of Music, Division of Musicology & Ethnomusicology Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837), a student of Mozart and Haydn, and colleague of Beethoven, made a spectacular ascent from child-prodigy to pianist- superstar. A composer with considerable output, he garnered enormous recognition as piano virtuoso and teacher. Acclaimed for his dazzling, beautifully clean, and elegant legato playing, his superb pedagogical skills made him a much sought after and highly paid teacher. This dissertation examines Hummel’s eminent role as piano pedagogue reassessing his legacy. Furthering previous research (e.g. Karl Benyovszky, Marion Barnum, Joel Sachs) with newly consulted archival material, this study focuses on the impact of Hummel on his students. Part One deals with Hummel’s biography and his seminal piano treatise, Ausführliche theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano- Forte-Spiel, vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an, bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung, 1828 (published in German, English, French, and Italian). Part Two discusses Hummel, the pedagogue; the impact on his star-students, notably Adolph Henselt, Ferdinand Hiller, and Sigismond Thalberg; his influence on musicians such as Chopin and Mendelssohn; and the spreading of his method throughout Europe and the US. Part Three deals with the precipitous decline of Hummel’s reputation, particularly after severe attacks by Robert Schumann. His recent resurgence as a musician of note is exemplified in a case study of the changes in the appreciation of the Septet in D Minor, one of Hummel’s most celebrated compositions. -

Part Two Patrons and Printers

PART TWO PATRONS AND PRINTERS CHAPTER VI PATRONAGE The Significance of Dedications The Elizabethan period was a watershed in the history of literary patronage. The printing press had provided a means for easier publication, distribution and availability of books; and therefore a great patron, the public, was accessible to all authors who managed to get Into print. In previous times there were too many discourage- ments and hardships to be borne so that writing attracted only the dedicated and clearly talented writer. In addition, generous patrons were not at all plentiful and most authors had to be engaged in other occupations to make a living. In the last half of the sixteenth century, a far-reaching change is easily discernible. By that time there were more writers than there were patrons, and a noticeable change occurred In the relationship between patron and protge'. In- stead of a writer quietly producing a piece of literature for his patron's circle of friends, as he would have done in medieval times, he was now merely one of a crowd of unattached suitors clamouring for the favours and benefits of the rich. Only a fortunate few were able to find a patron generous enough to enable them to live by their pen. 1 Most had to work at other vocations and/or cultivate the patronage of the public and the publishers. •The fact that only a small number of persons had more than a few works dedicated to them indicates the difficulty in finding a beneficent patron. An examination of 568 dedications of religious works reveals that only ten &catees received more than ten dedications and only twelve received between four and nine. -

Power Gold: Concentration Game CMA Sets Trend for Industry

February 10, 2020, Issue 691 Power Gold: Concentration Game This edition of Country Aircheck’s Power Gold is led by eight artists who combine for 46 of the Top 100 most-heard Gold hits. Luke Bryan and Florida Georgia Line lead the parade with seven songs apiece, followed by Jason Aldean and Zac Brown Band with six each. Rounding out the top PG hit-makers are Kenny Chesney, Thomas Rhett, Blake Shelton and Carrie Underwood, all with five hits in the Top 100. One artist – Dierks Bentley – places four songs in this elite group, meaning that nine acts are responsible for 50% of the current Power Gold. More thoughts on that later. Twenty-three songs from 20 artists are new Luke Bryan to the Top 100 since we ran the list last year (CAW 1/14/19). Interestingly, four songs in that group are more than five years old and are actually making a return appearance to the PG 100. They are Tim McGraw’s “Live Like You Were Dying” (2004), Bentley’s “Free And Easy (Down The Staff Hearted: WNCY/Appleton, WI’s Shotgun Shannon, Luke Road I Go)” (2007), Bryan’s “I See You” (2015) and FGL’s “Sippin’ Reid, Charli McKenzie, Hannah, Dan Stone and PJ (l-r) show On Fire” (2015). off the station’s 23rd annual Y100 Country Cares for St. Jude This Top 100 Power Gold – along with the airplay information in Kids Radiothon total. the previous paragraph – is culled from Mediabase 24/7 and music airplay information from the Country Aircheck/Mediabase reporting panel for the week of January 26-Feb. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS APRIL 12, 2021 | PAGE 1 OF 20 BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] INSIDE Tenille Arts Overcomes Multiple Challenges En Route To An Unlikely First Top 10 Stapleton, Tenille Arts won’t be taking home any trophies from the 2019, it entered the chart dated Feb. 15, 2020, at No. 59, just Barrett 56th annual Academy of Country Music (ACM) Awards on weeks before COVID-19 threw businesses around the world Rule Charts April 18 — competitor Gabby Barrett received the new female into chaos. Shortly afterward, Reviver was out of the picture. >page 4 artist honor in advance — but Arts has already won big by Effective with the chart dated May 2, 19th & Grand — headed overcoming an extraordinary hurdle to claim a precedent- by CEO Hal Oven — was officially listed as the lone associated setting top 10 single with her first bona label. Reviver executive vp/GM Gator Mi- fide hit. chaels left to form a consultancy in April Clint Black Arts, who was named a finalist for new 2020 and tagged Arts and 19th & Grand ‘Circles’ TV female when nominations were unveiled as his initial clients. Former Reviver vp Feb. 26, moves to No. 9 on the Country Air- promotion Jim Malito likewise shifted to >page 11 play chart dated April 17 in her 61st week 19th & Grand, using the same title. Four on the list. Co-written with producer Alex of the five current 19th & Grand regionals Kline (Terri Clark, Erin Enderlin) and Alli- are also working the same territory they son Veltz Cruz (“Prayed for You”), “Some- worked at Reviver. -

John Marks Exits Spotify SIGN up HERE (FREE!)

April 2, 2021 The MusicRow Weekly Friday, April 2, 2021 John Marks Exits Spotify SIGN UP HERE (FREE!) If you were forwarded this newsletter and would like to receive it, sign up here. THIS WEEK’S HEADLINES John Marks Exits Spotify Scotty McCreery Signs With UMPG Nashville Brian Kelley Partners With Warner Music Nashville For Solo Music River House Artists/Sony Music Nashville Sign Georgia Webster Sony Music Publishing Renews With Tom Douglas John Marks has left his position as Global Director of Country Music at Spotify, effective March 31, 2021. Date Set For 64th Annual Grammy Awards Marks joined Spotify in 2015, as one of only two Nashville Spotify employees covering the country market. While at the company, Marks was instrumental in growing the music streaming platform’s Hot Country Styles Haury Signs With brand, championing new artists, and establishing Spotify’s footprint in Warner Chappell Music Nashville. He was an integral figure in building Spotify’s reputation as a Nashville global symbol for music consumption and discovery and a driver of country music culture; culminating 6 million followers and 5 billion Round Hill Inks Agreement streams as of 4th Quarter 2020. With Zach Crowell, Establishes Joint Venture Marks spent most of his career in programming and operations in With Tape Room terrestrial radio. He moved to Nashville in 2010 to work at SiriusXM, where he became Head of Country Music Programming. During his 5- Carrie Underwood Deepens year tenure at SiriusXM, he brought The Highway to prominence, helping Her Musical Legacy With ‘My to bring artists like Florida Georgia Line, Old Dominion, Kelsea Ballerini, Chase Rice, and Russell Dickerson to a national audience. -

Partbooks and the Music Collection Will Be Open from 12 May to 13 August 2016 in the Upper Library at Christ Church

Tudor Partbooks and the Music Collection will be open from 12 May to 13 August 2016 in the Upper Library at Christ Church. The exhibition showcases the music-books used by singers in the age of Queen Elizabeth I, with special emphasis on partbooks. This is the result of a successful collaboration with the Tudor Partbooks Project (Oxford University, Faculty of Music) and the Oxford Early Music Festival. The exhibition is curated by Dr John Milsom and Dr Cristina Neagu. Visiting hours: Monday - Friday 10.00 am - 1.00 pm 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm (provided there is a member of staff available in the Upper Library). The new exhibition opened with a concert by Magnificat, featuring pieces from the Christ Church Music Collection. This is one of the world’s premier vocal ensembles, internationally acclaimed for its performance of Renaissance choral masterpieces. Concert programme Robert White Christe qui lux Lamentations William Byrd Come to me grief O that most rare breast Thomas Tallis Salvator mundi (II) Salvator mundi (I) The concert was followed by a talk by Dr John Milsom, leading Tudor music scholar, and a drinks reception in the Cathedral. Tudor partbooks and the music collection Detail from Mus 864b choirbooks 1. CHOIRBOOK LAYOUT: A CLASSIC FOUR-VOICE MOTET In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, church choirs typically sang from large choirbooks, in which different areas of the double-page spread displayed the various voice-parts of a composition. This example shows the famous Ave Maria … virgo serena by Josquin Desprez. Each of the motet’s four voices is headed with a large capital A.