Professional Cooking Can Afford to Be Without Knowledge of Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instruction Manual Favourite Recipes Operating Instructions Procedure for Cooking and Smoking

...how to smoke & cook easily in a HELIA SMOKER Instruction Manual Favourite Recipes Operating instructions Procedure for cooking and smoking After removing all of the protective foils, preheat the oven to 1. Preheat: Turn thermostat control to the desired cooking 170°C for 1 hour prior to initial use. Subsequently switch the heat Temperaturee. As soon as the Temperaturee is reached the off, fill the smoking pan with sawdust and 1 tablespoon of water green lamp goes out. The timer can be switched on simul- and place it on the heating element. Slightly close the door and taneously in order to preheat more quickly. set the timer to 15 mins. 2. Fill the smoking pan with sawdust and place on the heating Allow the closed oven to cool down for at least 2 hours. Do not element in the oven, you may add juniper granules. fully close the door during the pre-heating process. Close it just 3. Place the dripping pan and directly above, the correspon- enough that approximately the same quantity of smoke escapes ding grill with the item(s) to be smoked onto the lower bar of as from a cigar. This process should also be carried out for the the device, if necessary, add an additional grill with item(s) further smoking processes, until such time as the oven is com- to be smoked on the upper bar, and close the door only up the pletely black. marking „ZU“. Do not clean the interior, just wipe off any coarse soiling. 4. Switch timer on (Set to 1x 10 - 15 minutes). -

Sole a La Walewska in Spring a New Take on an Escoffier Classic

SPRING 2017 Sole a la Walewska in Spring A new take on an Escoffier classic culinary + art where art and food intersect gather round for cure guanciale Sunday supper in six steps sizzle The American Culinary Federation features Quarterly for Students of Cooking NEXT Publisher 20 Culinary + Art IssUE American Culinary Federation, Inc. The intersection of art and food happens on and • the digital chef Editor-in-Chief off the plate for these chefs. • popsicles Stacy Gammill 26 Sunday Suppers • forager Senior Editor Karen Bennett Mathis, APR Chefs have embraced family-style dining and discovered a way to fill empty seats on typically Graphic Designer slow nights. David Ristau Contributing Editors 32 Food Historian Rob Benes Few professions are as immersed in Suzanne Hall Ethel Hammer history as the culinary profession. 20 26 32 Maggie Hennessy Direct all editorial, advertising and subscription inquiries to: American Culinary Federation, Inc. 180 Center Place Way departments St. Augustine, FL 32095 (800) 624-9458 4 President’s Message [email protected] ACF president Thomas Macrina, CEC, CCA, AAC, emphasizes creativity and Subscribe to Sizzle: challenging yourself. www.acfchefs.org/sizzle 6 Amuse-Bouche For information about ACF certification and membership, Student news, opportunities, events and more. go to www.acfchefs.org. 12 Slice of Life Rebekah Borgstede walks us through a memorable day in her apprenticeship at during a Denver Broncos play-off game. @ACFChefs @acfchefs @acf_chefs 14 Classical V. Modern Sizzle: The American Culinary Federation Quarterly Carlos Villanueva and Huizi Qian of Cloud Catering and Events, Long Island City, for Students of Cooking (ISSN 1548-1441), New York, demonstrate two ways of making a Filet de Sole Walewska. -

Download the 2019 Maine Lobster Chef of The

HARVEST ON THE HARBOR MAINE LOBSTER CHEF OF THE YEAR 2019 RECIPES Note, these recipes are as provided by the chefs. The Chefs are listed, with their recipes, in alphabetical order. THOMAS BARTHELMES | Central Provisions, Portland Maine Lobster Chef of the Year 2019 People’s Choice LOBSTER TOAST lobster mousseline on toasted milk bread with lobster kewpie mayonnaise, tomatillo-seaweed relish, and green shiso Makes 8 portions For the mousseline: 8 ounces lobster meat, raw and removed from the shell 1 egg ½ t salt ½ t white soy ½ C heavy cream 1 t grated ginger ½ t grated garlic 1/8 t sansho pepper 1 T finely chopped chives 1 T brunoised shallot 4 ounces poached lobster meat, removed from the shell and chopped Combine the 8 ounces of raw lobster with egg, salt, white soy, ginger, sansho pepper and garlic and blend in a food processor until homogenous. With the machine running slowly stream in the heavy cream. Remove the mousseline and pass through a fine tamis. Fold in chives, shallot and chopped lobster and poach a small test wrapped in plastic wrap in simmering water. Adjust seasoning if necessary. For the lobster kewpie mayonnaise: 4 lobster bodies, removed of lungs, antennae and outer shell Canola oil 1 egg yolk per cup of oil Yuzu juice, to taste MSG, to taste Sugar, to taste Salt, to taste Thoroughly clean the lobster bodies and drain well. Place in a pot that will fit them comfortably and just cover with canola oil. Slowly heat the lobster bodies and oil until the shells begin to lightly sizzle—once the sizzling subsides, monitor the oil closely. -

Food Production

Food Production Best of Chinese cooking-Sanjeev Kapoor- Popular Prakashan, Mumbai- 2003 Food Preparation for the professional- David A. Mizer, Mary Porter, Beth Sonnier, Karen Eich Drummond- John Wiley and Sons,Inc- Canada- 2000 A concise encyclopedia of gastronomy- Andre l. simon- The Overlook Press- 1981, Mastering the art of French Cooking- Julia Child, louisette bertholle, Simone Classical cooking- The Modern way- Eugen Pauli, 2nd edition,Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York 1989, B- 4 Beck, , penguin books, 2009, b-5 Joy of cooking- Irma S. Rombauer, Marion Rombauer Becker, The New American Liabrary, New York, 1974- b-6 Syllabus- 1 Introduction to cookery- A. Level of skills and experience B. Attitude and behavior in Kitchen C. Personal hygiene D. Uniforms and protective clothing E. Safety procedure in handling equipment 2. Culinary history- Origin of modern cookery 3. Hierarchy area of department and kitchen a. Classical brigade b. Modern Staffng in various category hotels c. Roles of executive chef d. Duties and responsibilities of various chefs e. Co-opeartion with other departments 4. Culinary terms- A. list of (common and basic) terms B. Explanation with examples 5. Aims and objectives of cooking food A. Aims and objectives of cooking food B. Various Textures C. Various Consisatencies D. Techniques used in pre-preparation E. Techniques used in preparation 6. Basic Principles of Food Production-1 i) Vegetable and Fruit Cookery A. Introduction – Classification of Vegetables B. Pigments and colour Changes C. Effects of heat on vegetables D. Cuts of vegetables E. Classification of fruits F. Uses of fruits in cookery G. Salads and salad dressings ii) Stocks A. -

Introduction to Culinary Technology & Methods

S T Introduction to Culinary Technology & Methods U D Labels E tool used for identifying food items within the kitchen according to date N prepared or other important factors T V Use-by-Date O regulated date for food safety; used to protect consumers and inform food C preparers of freshness A B Ready-to-Eat Foods U food which is ready for human consumption; generally handled with latex L A gloves for safety R Y Refrigeration Requirements temperature levels used to keep food fresh; generally regulated by local H entities A N D Mis en Place O term referencing preparation for food and tools used with a particular dish; U French for “put in place” T Portion Cups used to hold desired amounts of ingredients for food preparation Cheese Cloth kitchen tool used for many purposes, including moisture removal Pan-Frying cooking technique used to fry foods with oils in a frying pan Smoke Point temperature at which oil will begin to smoke Portion Control regulating the size of a serving Cutting Board solid surface made of plastic, wood or other materials used to safely cut food products Round Cuts cutting techniques which include the rondelle and diagonal methods Accompanies: Introduction to Culinary Technology & Methods 1 S T Introduction to Culinary Technology & Methods U D Rondelle Cut E cutting round foods into round slices N T Diagonal Cut V cutting foods at angles to achieve oval shaped slices O C Stick Cuts A cutting techniques that include batonnet and julienne B U Batonnet Cuts L A precise cutting method used to achieve slices of a particular -

Catering & Private Events Menu

RIO TINTORIO STADIUM stadium 2019 Catering & Private Events Menu stadium You’re INVITED Take a seat at our family table, Rio Tinto Stadium where over 30 years of culinary and 9256 South State Street Sandy, Utah 84070 hospitality experience come together with heart and commitment. We’ve Sarah Fults built our reputation on offering (801)727-2742 world class best service in showcase [email protected] locations. From club seats to trophy room ceremonies, your occasion is our passion. You’re invited to cherish this moment. Chef David Williams is a Your Chef Maui, Hawaii native. He has made a name for himself on David Williams the island of Maui working Chef David Williams has already made a name from himself in in some of the greatest Utah being featured on live TV on KSL for his successful “Brunch restaurants and hotels on with Santa” at the Sheraton Salt Lake City and a face for Levy in the the island. His move to the community volunteering for numerous benefits and participating as continental United States the Program advisory committee for the SLCC Culinary Academy. His favorite cuisines consist of Filipino, Italian, Hawaiian, Japanese, has been an easy transition Thai, and classical French. His Hobbies are surfing, spear fishing, and he spends most of waterfall base-jumping, running, weight lifting, and of course, cooking. his free-time with his wife David has spent 5 years with the Four Seasons brand cooking for and two sons hiking the celebrities, princes and princesses, high profile actors and actresses, Wasatch front professional athletes, popstars, rock stars, and anything in between. -

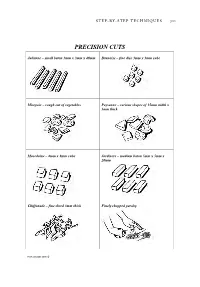

Precision Cuts

STEP-BY-STEP TECHNIQUES 311 PRECISION CUTS Julienne – small baton 3mm x 3mm x 40mm Brunoise – fine dice 3mm x 3mm cube Mirepoix – rough cut of vegetables Paysanne – various shapes of 15mm width x 3mm thick Macedoine – 8mm x 8mm cube Jardinere – medium baton 5mm x 5mm x 20mm Chiffonade – fine shred 3mm thick Finely chopped parsley HEIA October 2009 © Commonsense YR GJ 5ppNEW.indd 311 8/12/09 10:46:26 AM 312 STEP-BY-STEP TECHNIQUES PREPARATION OF A ROUX 1. Melt butter or margarine in 2. Remove from heat, add flour, and stir saucepan. with wooden spoon until a smooth paste is formed. 3. Return to a low heat and cook for 4. Remove from heat and slowly add further minute – do not brown. milk, stir thoroughly. 5. Return to heat and stir until boils and Cooks note: To prevent a skim layer thickens. forming on top of a sauce, push a sheet of plastic wrap down onto the sauce to exclude all air. HEIA October 2009 © Commonsense YR GJ 5ppNEW.indd 312 8/12/09 10:46:26 AM STEP-BY-STEP TECHNIQUES 313 CRUSHING GARLIC 1. Place unpeeled garlic clove on a 2. Remove skin and roughly chop. chopping board. Using the flat of knife blade, press down firmly with heel of hand. 3. Add a large pinch salt; hold knife Cooks note: Crushed garlic can be stored firmly and work garlic into a paste in an airtight jar in the refrigerator for up applying pressure to toe of blade. to one month. HEIA October 2009 © Commonsense YR GJ 5ppNEW.indd 313 8/12/09 10:46:26 AM 314 STEP-BY-STEP TECHNIQUES BLANCHING AND PEELING TOMATO 1. -

Basic Knife Skills Guide.Pdf

Basic Knife Skills Basic knife skills are an important component of any culinarian’s repertoire - whether you plan to earn a living in the kitchen, or simply please yourself, your friends, and your family. Learning to wield a knife correctly will speed up your prep time, and food products fashioned in uniform shapes and sizes will help guarantee even cooking throughout a dish. In addition, the mastery of certain classic knife cuts and methodology will vastly improve the look of your food, garnishes and plate presentations. Overview of the lesson Goal: to impart a basic knowledge of knife safety, knife construction, the most commonly used kitchen knives, a few classic knife cuts. Equipment You won’t need any truly special equipment for this lesson. The bare minimum requirements are: A sturdy cutting board A (sharp!) chef’s knife A (sharp!) paring knife A vegetable peeler Hopefully, you also own a steel (a tool to hone your knife edge between sharpenings and intermittently during use). If you have a tourne or bird’s beak knife, that’s great – but not absolutely necessary. Shopping List Here’s a list of what you might like to have on hand if you want to try all the techniques I’m going to present: A bag of baking potatoes A bunch of carrots A few large, firm onions A few handfuls of leafy herbs or vegetables (large-leaf basil or spinach would be ideal, but cabbage will suffice) A couple of bell peppers Knife Safety The safe use of knives is imperative for obvious reasons. -

2007 Family & Consumer Sciences Summer Conference

2007 Family & Consumer Sciences Summer Conference Knife Skills Presented by: Chef John V. Johnson, CCC, CCE, AAC Riverton High School Riverton, Utah 2007 Family & Consumer Sciences Summer Conference Knife Skills Objectives: By the end of this class, students will be able to • list different knives and their uses. • handle and sharpen knives safely. • identify and prepare various knife cuts. Class Sequence: • Introductions • Knife skills discussion • Knife identification • Handling and sharpening knives • Demonstration of different knife cuts • Student participation of knife cuts • Kitchen sanitation 2007 Family & Consumer Sciences Summer Conference Knife Skills Equipment: Each student will need to bring a knife kit consisting of: • 1 chef knife • 1 paring knife • 1 vegetable peeler • 1 sharpening steel If possible, a 3 sided sharpening stone for instructor demonstration. Food: The following should be provided for each student: • 1 onion • 2 carrots • 2 ribs celery • 1 orange • 2 potatoes • 1 green pepper • several mushrooms In addition to the above, the instructor will also need: • 1 bulb garlic • a few fresh basil leaves The cook's knife: The most important kitchen tool 1. The sturdy spine of the blade can be used to break up small bones or shellfish. 2. The front of the blade is suitable for many small cutting jobs. It is particularly useful for chopping onions, mushrooms, garlic and other small vegetables. 3. The mid section of the blade is remarkably appropriate for either firm or soft food.The gentle curve of the blade is ideal for mincing of leeks, chives, parsley etc. Caution: Cook's knives purposely have been ground extra thin for the ultimate cutting performance. -

Pairing Focus WACS Cooking With

S C W A WorldIssue 07 Official Magazine Of the WchefsOrld assOciatiOn Of chefs sOcieties Anno 2013 January - June Focus Pairing wacs cooking with How to Feed the Food & Young Chefs Recipes by Planet in the Future Tea Marriage & Heritage Pascal Barbot TRUE TASTE. GLOBAL EXPERTISE. Products developed by our chefs to deliver made-from-scratch taste. Prepared exclusively for foodservice, Custom Culinary® products are crafted with uncompromising detail and feature only the finest ingredients from across the globe for true, authentic flavor in every experience. True Versatility For amazing entrees, soups and sides, our food base and sauce systems offer endless opportunities. True Performance Consistent and convenient with made-from-scratch taste and inspired results in just minutes. True Inspiration Chef-developed, on-trend flavors that take your menu, and your signature dishes, to the next level. PROUD SPONSOR OF THE HANS BUESCHKENS JUNIOR CHEFS CHALLENGE AS WELL AS THE TRAIN THE TRAINER PROGRAM REPRESENTED IN AUSTRALIA P CANADA P COLOMBIA P C O S T A R I C A P HONG KONG P INDIA P MALAYSIA P MEXICO P MIDDLE EAST P SINGAPORE P SPAIN SAUCES BASES COATINGS SEASONINGS BLEED: 446mm x 296mm TRIM: 440mm x 290mm LIVE: 420mm x 270mm TRUE TASTE. GLOBAL EXPERTISE. Products developed by our chefs to deliver made-from-scratch taste. Prepared exclusively for foodservice, Custom Culinary® products are crafted with uncompromising detail and feature only the finest ingredients from across the globe for true, authentic flavor in every experience. True Versatility For amazing entrees, soups and sides, our food base and sauce systems offer endless opportunities. -

Food Service/Culinary Arts Test Number

Name_____________________________________ Period_____ Due Date /Test Date____________ Comprehensive Study Guide Definitions (Culinary Arts – 50 points) Careers in Foodservice: Chef - highly trained and responsible head cook. Caterer - provides foodservice for special social events. Side work – example: filling salt and pepper shakers. Customer - carries the major responsibility of the hosting personnel. Offend a coworker - listen carefully to the coworker and apologize. Two main areas of a foodservice establishment - The Back-of-the-House and the Front- of-the-House Three skills to be successful in the foodservice industry - Work ethic, math and measuring Back of the house job - Cook is an example Brigade - system that assigns responsibility to the kitchen staff. Server - front of the house, responsible for presenting the bill to the customer. Front of the house - serving the guests. Poor Communication – Majority of staff problems Safety and Sanitation: HAACP system- managing sanitary conditions through a system of critical control points. Primary causes of food-borne illness - the food service workers. Toxin - Poison produced by bacteria in food FIFO (first in, first out,) - the foods that have been in the holding area the longest will be used first. Temperature above 40 degrees F - Danger for refrigerators Hepatitis A - Fecal bacteria disease transferred by improperly washed hands and/or coughing/sneezing Staphylococcus - contact of human mucus, food poisoning outbreaks associated with improperly handling foods before -

Prochef® Certification Program Level I Exam Study Guide

ProChef ® Certification Program Level I Exam Study Guide CIA Consulting Department, Hyde Park, New York Copyright © 2019 The Culinary Institute of America All Rights Reserved This manual is published and copyrighted by The Culinary Institute of America. Copying, duplicating, selling or otherwise distributing this product is hereby expressly forbidden except by prior written consent of The Culinary Institute of America. Welcome, ProChef Certification Candidate! Congratulations on making the decision to validate the skills you’ve gained as a professional culinarian. You have committed to a rigorous process that offers you the opportunity to not only earn a valuable professional certification and promote yourself with a mark of accomplishment, but also help advance our industry. The ProChef Certification exam, and the skills you practice preparing for it, will challenge you to be the very best you can be. During your time in the program, be sure to take note of all the experience has to offer. You’ll want to recall these memories when sharing your knowledge with colleagues who will follow in your footsteps to gain their ProChef certification. At any time in the process, please feel free to share your thoughts with me, or any of the exam evaluators and staff. We value your insight as we continually strive to offer the best, most effective certification program. Thank you for your pride in our profession, commitment to lifelong learning, and spirit of giving back to the industry we all love. We are truly happy you have chosen to embark on this journey, and look forward to your successfully completing the program and representing the ProChef ideals as you go forward in your career.