Walking Tour Guide Notes: ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas E. Wolfe: Valuing the Life and Work of an Appalachian Regionalist Artist Within His Community

THOMAS E. WOLFE: VALUING THE LIFE AND WORK OF AN APPALACHIAN REGIONALIST ARTIST WITHIN HIS COMMUNITY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Susannah L. Van Horn, M.A. Graduate Program in Art Education The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Dr. James Sanders, Advisor Dr. Christine Ballengee Morris Dr. Sydney Walker Copyright by Susannah L. Van Horn, M.A. 2012 Abstract The purpose of my research is to offer insight into the life and work of Thomas E. Wolfe, who exhibits self-determination both as an artist and as an art educator in an Appalachian region of Southeastern Ohio. By presenting Wolfe’s life story, I make connections to the influences of culture, social experiences, regional identity, and family traditions that play to his development as an artist and art educator. My research questions focused on how he perceives himself, how others perceive his presence in the community, how his artwork is valued by his community and how his teaching practices helped develop a greater sense of community. Specifically, I was interested in which historical moments and events in his life that were important to him in recollecting his life story. In my narrative analysis of Wolfe’s life stories collected through oral history from Wolfe and 26 of his friends, family members, former students and community members, I considered selectivity, slippage, silence, intertextuality, and subjectivity to analyze his life story (Casey, 1993; Casey 1995-1996). Thomas Eugene Wolfe began making art as a child and evolved into an accomplished artist. -

2018 Fall Issue of the Scenic

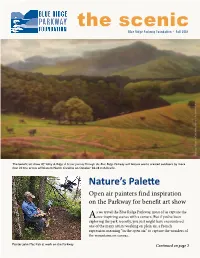

the scenic Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation - Fall 2018 Painting “Moses H. Cone Memorial Park” by John Mac Kah John Cone Memorial Park” by “Moses H. Painting The benefit art show Of Valley & Ridge: A Scenic Journey Through the Blue Ridge Parkway will feature works created outdoors by more than 20 fine artists of Western North Carolina on October 26-28 in Asheville. Nature’s Palette Open air painters find inspiration on the Parkway for benefit art show s we travel the Blue Ridge Parkway, most of us capture the Aawe-inspiring scenes with a camera. But if you’ve been exploring the park recently, you just might have encountered one of the many artists working en plein air, a French expression meaning “in the open air,” to capture the wonders of the mountains on canvas. Painter John Mac Kah at work on the Parkway Continued on page 2 Continued from page 1 Sitting in front of small easels with brushes and paint-smeared palettes in hand, these artists leave the walls of the studio behind to experience painting amid the landscape and fresh air. The Saints of Paint and Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation are inviting guests on a visual adventure with the benefit art show, Of Valley & Ridge: A Scenic Journey Through the Blue Ridge Parkway, showcasing the works of Western North Carolina fine artists from October 26 to 28 at Zealandia castle in Asheville, North Carolina. The show opens with a ticketed gala from 5 to 8 p.m., Friday, October 26, at the historical Tudor mansion, Zealandia, atop Beaucatcher Mountain. -

BLUE RIDGE BIKE PLAN for BUNCOMBE, Haywood, Henderson, Jackson, Madison, Swain, Transylvania Counties - North Carolina Acknowledgments

2013 BLUE RIDGE BIKE PLAN FOR BUNCOMBE, HAYWOOD, HENDERSON, JACKSON, MADISON, SWAIN, TRANSYLVANIA COUNTIES - NORTH CAROLINA ACKNOWLEDGMENTS SPECIAL THANKS Thank you to the more than 600 residents, bicycle shops and clubs, business owners and government employees who participated in meetings, surveys, and regional workgroups. We appreciate all your time and dedication to the development of this plan. STEERING COMMITTEE PROJECT TEAM Susan Anderson, City of Hendersonville Erica Anderson, AICP, Land of Sky Regional Council Paul Benson, Town of Waynesville Jon Beck, Land of Sky Regional Council Lynn Bowles, Madison County John Connell, Land of Sky Regional Council Matt Cable, Henderson County Vicki Eastland, French Broad River MPO Mike Calloway, NC Department of Transportation, Division 13 Christina Giles, Land of Sky Regional Council Claire Carleton, Haywood County Linda Giltz, AICP, Land of Sky Regional Council Kristy Carter, NC Department of Commerce/Appalachian Regional Commission Sarah Graham, Southwestern Commission Nathan Clark, Haywood County Josh King, AICP, Land of Sky RPO Daniel Cobb, City of Brevard Don Kostelec, AICP, Kostelec Planning, LLC Chris Cooper, Jackson County Philip Moore, Southwestern RPO Lucy Crown, Buncombe County Natalie Murdock, Land of Sky RPO Jill Edwards, Town of Black Mountain John Vine-Hodge, NC DOT, Division of Bicycle and Carolyn Fryberger, Town of Black Mountain Pedestrian Transportation Gerald Green, Jackson County Lyuba Zuyeva, French Broad River MPO Jessica Hocz, Madison County Preston Jacobsen, Haywood -

Asheville and Buncombe County

.1 (? Collection of American ILiteratur^ Ikqucatfjeb to Cfje ilibrarp of ttje Hnibersitp of i^ortf) Carolina "He gave back as rain that which he ^>^ receiveei as mist" D97/. !/-S7,9 00032761146 FOR USE ONLY IN THE NORTH CAROLINA COLLECTION w^ r I . \ STATEMENT November of last year The Asheville Citizen moved into its new INand permanent home at No. 25 Haywood Street. In celebration of that event The Citizen published a special edition, in which appeared two most interesting and highly instructive articles on the history of Western North Carolina and of Buncombe County, one prepared by Dr. F. A. Sondley, and the other by General Theodore F. Davidson, These two articles attracted widespread attention as they both narrated incidents and facts, many of which had never before been printed, and many of The Citizen's readers urged tliat these two articles be reprinted in pamphlet form, so as to be more easily read and pre- served for the future. At our request Dr. Sondley and General Davidson have both revised those two articles and have brought them up to date, and, in response to this request. The Citizen has had them printed and bound in this little volume. The Citizen believes that the public will be deeply interested in the facts set forth in this little volume, and is glad to have the oppor- tunity^ of performing what it believes is a great public service in hand- ing them down for future generations. The expense of securing the illustrations and the printing of this volume is considerably more than the . -

Look Homeward, Angel"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1994 The Problem of Time in Thomas Wolfe's "Look Homeward, Angel" Patrick M. Curran College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Curran, Patrick M., "The Problem of Time in Thomas Wolfe's "Look Homeward, Angel"" (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625884. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-7tbv-bk17 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PROBLEM OF TIME IN THOMAS WOLFE'S LOOK HOMEWARD, ANGEL A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts by Patrick M. Curran, Jr. 1994 ProQuest Number: 10629309 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10629309 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. -

Asheville African American Heritage Architectural Survey

Asheville African American Heritage Architectural Survey Submitted by: Owen & Eastlake LLC P.O. Box 10774 Columbus, Ohio 43201 Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 10 Historic Overview ......................................................................................................................... 12 Asheville, 1800–1860 ............................................................................................................... 12 Asheville 1865–1898 ................................................................................................................ 14 Jim Crow and Segregation ........................................................................................................ 20 The African American Community Responds .......................................................................... 26 The Boom Ends and the Great Depression ............................................................................... 32 World War II 1940-1945 .......................................................................................................... 37 Post-War, 1945–1965 .............................................................................................................. -

Thomas Wolfe and Look Homeward, Angel

Part 1: Thomas Wolfe and Look Homeward, Angel Prep Time: 10 minutes copying Look Homeward, Angel excerpt. Materials: Narratives about Thomas Wolfe, his family and his book Look Homeward, Angel. Links to online resources about Thomas Wolfe listed above. Attached Excerpt from Look Homeward, Angel Attached List “Grave Stone Symbolism” Procedure: 1. Share the narrative About Thomas Wolfe, his family and his book Look Homeward, Angel. 2. Discuss the life of Thomas Wolfe using links to online resources. Further information can come from your own research. 3. Distribute the excerpt from Look Homeward, Angel. Ask students to read the excerpt from Look Homeward, Angel, focusing their attention on the angels and ghosts in the passage. Narratives: Thomas Wolfe, his family and his book Look Homeward, Angel. “I don't know yet what I am capable of doing," wrote Thomas Wolfe at the age of twenty- three, "but, by God, I have genius—I know it too well to blush behind it." While in Europe in the summer of 1926 he began writing the first version of a novel, O Lost, which eventually evolved into Look Homeward, Angel. In 1929, with the publication of Look Homeward, Angel, Wolfe gave the world proof of his genius. Wolfe said that Look Homeward, Angel is "a book made out of my life." It tells the coming-of-age story of Eugene Gant, whose restlessness and yearning to experience life to the fullest take him from his rural home in North Carolina to Harvard University. Thomas Wolfe was born in Asheville, North Carolina, in 1900 and was the youngest of eight children of William Oliver Wolfe (1851–1922) and Julia Elizabeth Westall (1860– 1945). -

Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers

Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers APPALACHIAN Cultural Resources Workshop Papers Papers presented at the workshop held at Owens Hall, University of North Carolina- Asheville on April 1 and 2, 1991 Edited by Ruthanne Livaditis Mitchel 1993 National Park Service, Southeast Regional Office Office of Cultural Resources Cultural Resources Planning Division TABLE OF CONTENTS appalachian/index.htm Last Updated: 30-Sep-2008 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/sero/appalachian/index.htm[7/12/2012 8:13:52 AM] Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers (Table of Contents) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Cover photo from the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives. A 1941 view of Mabry Mill during restoration work. An Overview Of The Workshop Proceedings Ruthanne Livaditis Mitchell Historical Significance Of The Blue Ridge Parkway Ian Firth The Peaks of Otter And The Johnson Farm On The Blue Ridge Parkway Jean Haskell Speer Identification And Preservation Of Nineteenth And Twentieth Century Homesites In The Pisgah and Nantahala National Forests Rodney J. Snedeker and Michael A. Harmon Rural Historic Landscapes And Interpretive Planning On Our Southern National Forests Delce Dyer and Quentin Bass Fish Weirs As Part Of The Cultural Landscape Anne Frazer Rogers Southern Appalachia And The New South Ideal: Asheville As A Case Study In Development Kent Cave Cumberland Homesteads, A Resettlement Community Of -

Look Homeward, Angel Excerpt- Chapter 8 Thomas Wolfe Bullied At

Look Homeward, Angel Excerpt- Chapter 8 Thomas Wolfe Bullied At school, [Eugene] was a desperate and hunted little animal. The herd, infallible in its banded instinct, knew at once that a stranger had been thrust into it, and it was merciless at the hunt. As the lunch-time recess came, Eugene, clutching his big grease-stained bag, would rush for the playground pursued by the yelping pack. The leaders, two or three big louts of advanced age and deficient mentality, pressed closely about him, calling out suppliantly, "You know me, 'Gene. You know me"; and still racing for the far end, he would open his bag and hurl to them one of his big sandwiches, which stayed them for a moment, as they fell upon its possessor and clawed it to fragments, but they were upon him in a moment more with the same yelping insistence, hunting him down into a corner of the fence, and pressing in with outstretched paws and wild entreaty. He would give them what he had, sometimes with a momentary gust of fury, tearing away from a greedy hand half of a sandwich and devouring it. When they saw he had no more to give, they went away. Look Homeward, Angel Excerpts- Chapter 9 Wolfe the Bully Example #1 Eugene had no interest in pogroms, but it was a fetich with Max. The chief object of their torture was a little furtive-faced boy, whose name was Isaac Lipinski. They pounced cattishly at him when he appeared, harried him down alleys, over fences, across yards, into barns, stables, and his own house; he moved with amazing speed and stealth, escaping fantastically, teasing them to the pursuit, thumbing his fingers at them, … Example #2 But the whiteheaded children of Pigtail Alley they hated without humor, without any mitigation of a most bitter and alienate hate. -

P-T Conditions of Selected Samples Across the Blue Ridge Province Breana A

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 1-1-2012 P-T Conditions of Selected Samples Across the Blue Ridge Province Breana A. Felix [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Felix, Breana A., "P-T Conditions of Selected Samples Across the Blue Ridge Province" (2012). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 300. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. P-T CONDITIONS OF SELECTED SAMPLES ACROSS THE BLUE RIDGE PROVINCE A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Physical and Applied Science by Breana A. Felix Approved by Dr. Aley El-Shazly Dr. William Niemann Marshall University July 2012 ©2012 Breana A. Felix ALL RIGHTS RESERVED II ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Aley El-Shazly for all the hard work and time he has put into helping me with my thesis. He has been a great mentor and has always looked out for my best interest. Whenever I needed him, he was always there for me and I am really grateful for it. I would also like to acknowledge the rest of the Geology Department for their contribution and funding, along with the students who have supported me and kept me sane. -

James Bolles Postcard Collection, Ca. 1910-1960, Ph.C.114

• PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION 114 James Bolles Postcard Collection, ca. 1910-1960, Ph.C.114 North Carolina State Archives, Division of Historical Resources Raleigh, North Carolina 27699-4614 Contact Information Division of Historical Resources North Carolina State Archives 4614 Mail Service Center Raleigh, North Carolina 27699-4614 USA Phone: 919/807-7310 Fax: 919/733-1354 Email: [email protected] URL: http:// wv·.r\v.ah.dcr .state.nc. us/archives/ Processed by Kim Andersen Cumber • Date Completed 22 August 2006 Descriptive Summary Title James Bolles Postcard Collection, ca. 1910-1960, Ph.C.114 Creator James Bolles Abstract: Early 201h century postcards and picture souvenir packets c.191 0-1960 depicting western North Carolina scenes and historic sites including Biltmore House, Pisgah National Forest, various scenes, buildings, and businesses in Asheville and surrounding area, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and much more. All six • picture souvenir packets were published by the Asheville Post Card Co., Asheville, Page 1 of 11 NC, as were most of the loose postcards. A few postcards from other states are also included. Extent 58 loose postcards and 6 picture souvenir packets Repository North Carolina State Archives, Division of Historical Resources Information for Users Access Restrictions Open for research. Usage Restrictions Images may be subject to copyright. State Archives does not own copyright to images in this collection. Copyright is retained by the authors of these materials, or their descendants, as stipulated by United States copyright law (Title 17 US Code). Individual researchers are responsible for using these materials in conformance with copyright law as well as any donor restrictions accompanying the materials. -

Bernard Elias Interview Log Location: UNC-Asheville Library Date: 6/24/03 Interview by Philip (Ted) Coyle Log by Tonya Teague

Bernard Elias Interview Log Location: UNC-Asheville Library Date: 6/24/03 Interview by Philip (Ted) Coyle Log by Tonya Teague 001 Introduction 004 Bernard Elias' background 006 Family history, Duke University as family tradition 038 While Mr. Elias studied economics, he initially worked with photography after graduating from Duke; discussion of those experiences. 100 Mr. Elias' returning to Asheville 112 Mr. Elias' environmental views, and the origin of his views, the Boy Scouts. 137 Involvement with the Carolina Mountain Club 148 Working for the Acousta paper plant 169 Fliking with the Carolina Mountain Club 179 Comparing hiking in the 1940's to hiking in more recent decades, particularly the 1970's 224 The status of the Blue Ridge Parkway construction in 1941, the year Mr. Elias joined the Carolina Mountain Club. 238 Mr. Elias' memories of Sam Williams, the first superintendent of the Parkway 299 Development of Mr. Elias' friendship with Granville Liles 393 Discussion of Granville Liles' work with Hugh Morton 424 End of Side One, Tape One. Side Two, Tape One BOOl Further discussion of Granville Liles and Hugh Morton, and their involvement with the building of the Linn Cove Viaduct B020 The transition of the Carolina Mountain Club from a political advocacy group to a trail maintenance group. B043 The relationship between the Carolina Mountain Club and the Mountains to the Sea Trail. B085 Conservation issues that Mr. Elias hopes people will work on over the next fifty years. B128 Mr. Elias' likes and dislikes of the Blue Ridge Parkway B158 The story behind the red hat that Mr.