Al-Jazeera's Democratizing Role and the Rise Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Al Jazeera As Covered in the U.S. Embassy Cables Published by Wikileaks

Al Jazeera As Covered in the U.S. Embassy Cables Published by Wikileaks Compiled by Maximilian C. Forte To accompany the article titled, “Al Jazeera and U.S. Foreign Policy: What WikiLeaks’ U.S. Embassy Cables Reveal about U.S. Pressure and Propaganda” 2011-09-21 ZERO ANTHROPOLOGY http://openanthropology.org Cable Viewer Viewing cable 04MANAMA1387, MINISTER OF INFORMATION DISCUSSES AL JAZEERA AND If you are new to these pages, please read an introduction on the structure of a cable as well as how to discuss them with others. See also the FAQs Reference ID Created Released Classification Origin 04MANAMA1387 2004-09-08 14:27 2011-08-30 01:44 CONFIDENTIAL Embassy Manama This record is a partial extract of the original cable. The full text of the original cable is not available. C O N F I D E N T I A L MANAMA 001387 SIPDIS STATE FOR NEA/ARP, NEA/PPD E.O. 12958: DECL: 09/07/2014 TAGS: PREL KPAO OIIP KMPI BA SUBJECT: MINISTER OF INFORMATION DISCUSSES AL JAZEERA AND IRAQ Classified By: Ambassador William T. Monroe for Reasons 1.4 (b) and (d) ¶1. (C) Al Jazeera Satellite Channel and Iraq dominated the conversation during the Ambassador's Sept. 6 introductory call on Minister of Information Nabeel bin Yaqoob Al Hamer. Currently released so far... The Minister said that he had directed Bahrain Satellite 251287 / 251,287 Television to stop airing the videotapes on abductions and kidnappings in Iraq during news broadcasts because airing Articles them serves no good purpose. He mentioned that the GOB had also spoken to Al Jazeera Satellite Channel and Al Arabiyya Brazil about not airing the hostage videotapes. -

Jerusalem's Women

Jerusalem’s Women The Growth and Development of Palestinian Women’s movement in Jerusalem during the British Mandate period (1920s-1940s) Nadia Harhash Table of Contents Jerusalem’s Women 1 Nadia Harhash 1 Abstract 5 Appreciations 7 Abbreviations 8 Part One : Research Methodological Outline 9 I Problem Statement and Objectives 10 II Research Tools and Methodology 15 III Boundaries and Limitations 19 IV Literature Review 27 Part Two : The Growth and Development of the Palestinian Women’s Movement in Jerusalem During the British Mandate (1920s-1940s) 33 1 Introduction 34 2 The Photo 41 4 An Overview of the Political Context 47 5 Women Education and Professional Development 53 6 The Emergence of Charitable Societies and Rise of Women Movement 65 7 Rise of Women’s Movement 69 8 Women’s Writers and their contribution 93 9 Biographical Appendix of Women Activists 107 10 Conclusion 135 11 Bibliography 145 Annexes 152 III Photos 153 Documents 154 (Endnotes) 155 ||||| Jerusalem’s Women ||||| Abstract The research discusses the development of the women’s movement in Palestine in the early British Mandate period through a photo that was taken in 1945 in Jerusalem during a meeting of women activists from Palestine with the renowned Egyptian feminist Huda Sha’rawi. The photo sheds light on the side of Palestinian society that hasn’t been well explored or realized by today’s Palestinians. It shows women in a different role than a constructed “traditional” or “authentic” one. The photo gives insights into a particular constituency of the Palestinian women’s movement: urban, secular-modernity women activists from the upper echelons of Palestinian society of the time, women without veils, contributing to certain political and social movements that shaped Palestinian life at the time and connected with other Arab women activists. -

“The Voice of the Voiceless” News Production and Journalistic Practice at Al Jazeera English

STOCKHOLM UNIVERSITY Department of Social Anthropology “The Voice of the Voiceless” News production and journalistic practice at Al Jazeera English Emma Nyrén i Master’s thesis Spring 2014 Supervisor: Paula Uimonen Abstract This thesis explores how the cultural and social media environments surrounding the journalism of Al Jazeera English are shaped by and shape the channel’s news practices. Al Jazeera English has been described as a contra-flow news organization in the global media landscape and this thesis discusses the different reasons why the channel is described in this way by looking at its origins, aims, characteristics and ideals. Based on interviews with Al Jazeera English journalists, news observations and two field observations in London, I argue that Al Jazeera English brings cultural and social sensitivity to its news reports by engaging with multiple in-depth perspectives, using local reporters and integrating citizen generated material. The channel’s early adoption of online technologies and citizen journalism also contributes to a more democratic news direction and gives the channel a wider spectrum of opinions and perspectives to choose between. By applying a comparative analysis built on similar studies within anthropology of news journalism differences and similarities within the journalistic practices can be detected, comparing Al Jazeera English’s journalism with journalism at other places and news organizations. These comparisons and discussions enables new understandings for how news is produced and negotiated within the global media landscape, and this gives the global citizen an improved comprehension of why the news, which shapes our appreciation of the world, looks like it does. -

Arabic Language and Literature 1979 - 2018

ARABIC LANGUAGEAND LITERATURE ARABIC LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE 1979 - 2018 ARABIC LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE A Fleeting Glimpse In the name of Allah and praise be unto Him Peace and blessings be upon His Messenger May Allah have mercy on King Faisal He bequeathed a rich humane legacy A great global endeavor An everlasting development enterprise An enlightened guidance He believed that the Ummah advances with knowledge And blossoms by celebrating scholars By appreciating the efforts of achievers In the fields of science and humanities After his passing -May Allah have mercy on his soul- His sons sensed the grand mission They took it upon themselves to embrace the task 6 They established the King Faisal Foundation To serve science and humanity Prince Abdullah Al-Faisal announced The idea of King Faisal Prize They believed in the idea Blessed the move Work started off, serving Islam and Arabic Followed by science and medicine to serve humanity Decades of effort and achievement Getting close to miracles With devotion and dedicated The Prize has been awarded To hundreds of scholars From different parts of the world The Prize has highlighted their works Recognized their achievements Never looking at race or color Nationality or religion This year, here we are Celebrating the Prize›s fortieth anniversary The year of maturity and fulfillment Of an enterprise that has lived on for years Serving humanity, Islam, and Muslims May Allah have mercy on the soul of the leader Al-Faisal The peerless eternal inspirer May Allah save Salman the eminent leader Preserve home of Islam, beacon of guidance. -

The Making of a Leftist Milieu: Anti-Colonialism, Anti-Fascism, and the Political Engagement of Intellectuals in Mandate Lebanon, 1920- 1948

THE MAKING OF A LEFTIST MILIEU: ANTI-COLONIALISM, ANTI-FASCISM, AND THE POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT OF INTELLECTUALS IN MANDATE LEBANON, 1920- 1948. A dissertation presented By Sana Tannoury Karam to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the field of History Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts December 2017 1 THE MAKING OF A LEFTIST MILIEU: ANTI-COLONIALISM, ANTI-FASCISM, AND THE POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT OF INTELLECTUALS IN MANDATE LEBANON, 1920- 1948. A dissertation presented By Sana Tannoury Karam ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University December 2017 2 This dissertation is an intellectual and cultural history of an invisible generation of leftists that were active in Lebanon, and more generally in the Levant, between the years 1920 and 1948. It chronicles the foundation and development of this intellectual milieu within the political Left, and how intellectuals interpreted leftist principles and struggled to maintain a fluid, ideologically non-rigid space, in which they incorporated an array of ideas and affinities, and formulated their own distinct worldviews. More broadly, this study is concerned with how intellectuals in the post-World War One period engaged with the political sphere and negotiated their presence within new structures of power. It explains the social, political, as well as personal contexts that prompted intellectuals embrace certain ideas. Using periodicals, personal papers, memoirs, and collections of primary material produced by this milieu, this dissertation argues that leftist intellectuals pushed to politicize the role and figure of the ‘intellectual’. -

灨G'c Hu鬥乜gba犮gd帖 GŸ #402;… D∏橑e抨gch曤gg

1 á©eÉ÷G ¢ù«FQ ádÉ°SQ 2 A É«°Uh’C G ¢ù∏› ¢ù«FQ ádÉ°SQ 3 á©eÉé∏d …ƒÄŸG ó«©dG ¥ÉaGB 1 7 ç GóM’C G RôHGC 2 4 á «dÉŸG èFÉàædG 2 8 ¿ ƒëfÉŸGh èeGÈdG ƒªYGO 4 2 A É«°Uh’C G ¢ù∏› 4 4 Ω ÉbQGC h ≥FÉ≤M Ω É©dG ‘ ÉgÉfó¡°T »àdG á«°SÉ«°ùdGh ájOÉ°üàb’G äÉHGô£°V’G ºZôH ô ªà°ùj å«M ,IôgOõe IôgÉ≤dÉH ᫵jôe’C G á©eÉ÷G âdGRÉe ,»°VÉŸG ‘ ‹hódG ôjó≤àdG ≈∏Y ∫ƒ°ü◊G ‘ ÜÓ£dGh ¢ùjQóàdG áÄ«g AÉ°†YGC ä GRÉ‚’E G øe OóY ≥«≤– ‘ á©eÉ÷G âë‚ Éªc ,IOó©àe ä’É› á «YÉæ°U ácô°T ∫hGC ¥ÓWGE äGRÉ‚’E G ∂∏J ºgGC øeh .áeÉ¡dG I AÉÑY øe êôîJ ájƒ«◊G É«LƒdƒæµàdG ∫É› ‘ ájô°üe á«LƒdƒæµJ ‹ hódG »KÓãdG OɪàY’G ≈∏Y ∫ɪY’C G IQGOGE á«∏c ∫ƒ°üMh ,á©eÉ÷G I QGOGE äÉ«∏c π°†a’C áFÉŸÉH óMGƒdG áÑ°ùf øª°V á«∏µdG π©L …òdG , á«Ä«ÑdG áeGóà°S’G ≥«≤ëàH ÉæeGõàdG QÉWGE ‘h .⁄É©dG ∫ƒM ∫ɪY’C G ≈ ∏Y ®ÉØ◊ÉH á«æ©ŸG äÉ©eÉ÷G ÚH IQGó°üdG ¿Éµe á©eÉ÷G â∏àMG É ªc ,É«≤jôaGC ∫ɪ°T á≤£æe ‘ á«Ä«ÑdG ÒjÉ©ŸGh ô°†N’C G ¿ƒ∏dG ä ÉKÉ©ÑfG áÑ°ùf ¢†ØîH ≥∏©àj ɪ«a Ωó≤àdG ≥«≤– á©eÉ÷G π°UGƒJ ™ ªà› ∞µ©j ,…ƒÄŸG Égó«©H á©eÉ÷G ∫ÉØàMG ÜGÎbG ™eh .¿ƒHôµdG π ªY ¬«LƒJ ¤GE ±ó¡J á«é«JGΰSG á£N áZÉ«°U ≈∏Y á©eÉ÷G , ᫪«∏©J á°ù°SƒD ªc Égõ«“ »àdG Iƒ≤dG •É≤f ≈∏Y RɵJQ’Gh á©eÉ÷G , ô°üŸ áeóÿG Ëó≤J øe É¡d ÊÉãdG ¿ô≤dG GC óÑJ »gh É¡à¡Lh ójó–h ø e OóY Ωɪ°†fG »°VÉŸG ΩÉ©dG ó¡°T .⁄É©dGh ,á«Hô©dG á≤£æŸGh Ö MQGC øjòdGh ,á©eÉ÷G AÉ«°UhGC ¢ù∏› ¤GE øjõ«ªàŸGh Oó÷G AÉ°†Y’C G ê QƒL á©eÉéH ΩÉ©dG QÉ°ûà°ùŸGh ¢ù«FôdG ÖFÉf ,¿hGôH É°ù«d :ºgh ,º¡H á ©eÉéH á«dhódG ¿ƒÄ°ûdGh á«°SÉ«°ùdG Ωƒ∏©dG PÉà°SGC ,¿hGôH ¿ÉãjÉfh ,¿hÉJ , …hÉeôa »∏Yh ,§°Sh’C G ¥ô°ûdG äÉ°SGQO á£HGQ ¢ù«FQh ø£æ°TGh êQƒL â aƒ°ShôµjÉe ácô°T ¢ù«FQh á«ŸÉ©dG âaƒ°ShôµjÉe ácô°T ¢ù«FQ ÖFÉf 1 00 ‹GƒM òæe á©eÉ÷G IÉC °ûf òæe -

Al Jazeera's Expansion: News Media Moments and Growth in Australia

Al Jazeera’s Expansion: News Media Moments and Growth in Australia PhD thesis by publication, 2017 Scott Bridges Institute of Governance and Policy Analysis University of Canberra ABSTRACT Al Jazeera was launched in 1996 by the government of Qatar as a small terrestrial news channel. In 2016 it is a global media company broadcasting news, sport and entertainment around the world in multiple languages. Devised as an outward- looking news organisation by the small nation’s then new emir, Al Jazeera was, and is, a key part of a larger soft diplomatic and brand-building project — through Al Jazeera, Qatar projects a liberal face to the world and exerts influence in regional and global affairs. Expansion is central to Al Jazeera’s mission as its soft diplomatic goals are only achieved through its audience being put to work on behalf of the state benefactor, much as a commercial broadcaster’s profit is achieved through its audience being put to work on behalf of advertisers. This thesis focuses on Al Jazeera English’s non-conventional expansion into the Australian market, helped along as it was by the channel’s turning point coverage of the 2011 Egyptian protests. This so-called “moment” attracted critical and popular acclaim for the network, especially in markets where there was still widespread suspicion about the Arab network, and it coincided with Al Jazeera’s signing of reciprocal broadcast agreements with the Australian public broadcasters. Through these deals, Al Jazeera has experienced the most success with building a broadcast audience in Australia. After unpacking Al Jazeera English’s Egyptian Revolution “moment”, and problematising the concept, this thesis seeks to formulate a theoretical framework for a news media turning point. -

Liste Des Chaînes Diablo DIABLO CHANNELS LISTS ALL HD (4000)

Maintenent disponible sur Diablo Pro Liste des chaînes Diablo DIABLO CHANNELS LISTS ALL HD (4000) – The only One Iptv you can rewind on your Favorite Channels 12H – 96H – Le Seul Iptv que vous pouvez faire marche arrière sur vos Canaux Préférés 12H – 96H – Video on demand – Movies – Series – Show (Espanol, English, Français) – Possibility of Recording MAG – DIABLO BOX – T2 – BUZZ – FORMULER *** – Possibilité d’enregistrer MAG- DIABLO BOX – T2 – BUZZ – FORMULER *** – VOD -VIDEOCLUB- FILM/MOVIES ARABIC(300+) – FILM/MOVIES ENGLISH (2000+) – FILM/MOVIES FRANCAIS (2000+) – VOD -VIDEOCLUB- PELICULA ESPANOL(20+) – KIDS ENGLISH (80+) – KIDS FRANCAIS (300+) – VOD -VIDEOCLUB- TV SHOWS ENGLISH (150+) – SERIES FRANCAIS (150+) – VOD -VIDEOCLUB- SPORTS – DOCUMENTARY/DOCUMENTAIRE – RAMADAN – SPECTACLES HUMOUR – COFFRET Diablo Channel List § Canaux FRENCH (212) § Canaux FRENCH QUEBEC § Canaux UTC FRENCH (17) § Canaux ARABIC (449) § Canaux UTC ARABIC (50) § Canaux CANADA ENGLISH (166) § Canaux USA ENGLISH (229) § Canaux SPORTS (178) § Canaux UNITED KINGDOM (113) § Canaux KIDS (52) § Canaux AFRICA (260) § Canaux HAITI (8) § Canaux TURKISH & ARMANIA (34) § Canaux ROMANIA (97) § Canaux PORTUGUESE (120) § Canaux BRAZIL (114) § Canaux ESPANA (163) § Canaux NEDERLAND (86) § Canaux ITALIAN (279) § Canaux CZECH REPUBLIC (90) § Canaux LATINO (644) § Canaux IRAN (52) § Canaux BELGIUM (30) § Canaux FILIPINO (18) § Canaux SPORTS ON DEMAND (145) § Canaux SPECIAL EVENTS (8) § Canaux MAJIK FILM / MOVIES (21) § Canaux GREEK (73) § Canaux CARAIBE (86) § Canaux XXX (88) -

Al JAZEERA MUBASHER LIVE and UNFILTERED

AL JAZEERA MUBASHER LIVE AND UNFILTERED We capture events while they happen. Raw. Unfiltered. And now. Launched in April 2005, Al Jazeera Mubasher bringing audiences the latest on political, social, is the first Middle Eastern 24-hour live news cultural and economic affairs. and events channel. Acting as the eyes and ears of the Arab world, we’re dedicated to When people want events as they happen, they giving viewers real-time footage of global turn to Al Jazeera Mubasher—live and uncut. and regional events. Remote feeds and on-the-ground cameras broadcast political gatherings, press conferences, discussions, and meetings, FROM OUR LENS, TO THE WORLD Zero editing. Zero distractions. It’s why the live From the stately halls of government buildings content on Al Jazeera Mubasher is accurate, to the gritty streets of the region’s most volatile impartial and must-see television. cities, we’re on the ground uncovering stories that escape mainstream news. It’s coverage At Al Jazeera Mubasher, we understand that that captures raw emotion. Passionate and we have an obligation to deliver breaking beautiful, we echo the voice of the people, coverage of the most important events in the and we bring it to the world. region. Because when news happens, our audiences count on us to bring it to them live and without a filter. AMERICAS SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA NORTH AFRICA EUROPE MIDDLE EAST ASIA PACIFIC BUREAUS BUREAUS BUREAUS BUREAUS BUREAUS BUREAUS Buenos Aires, Argentina Abuja, Nigeria Benghazi, Libya Ankara, Turkey Amman, Jordan Bangkok, Thailand Caracas, -

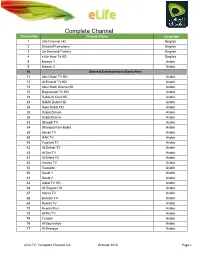

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

The Ohio State University

MAKING COMMON CAUSE?: WESTERN AND MIDDLE EASTERN FEMINISTS IN THE INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MOVEMENT, 1911-1948 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Charlotte E. Weber, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Leila J. Rupp, Adviser Professor Susan M. Hartmann _________________________ Adviser Professor Ellen Fleischmann Department of History ABSTRACT This dissertation exposes important junctures between feminism, imperialism, and orientalism by investigating the encounter between Western and Middle Eastern feminists in the first-wave international women’s movement. I focus primarily on the International Alliance of Women for Suffrage and Equal Citizenship, and to a lesser extent, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. By examining the interaction and exchanges among Western and Middle Eastern women (at conferences and through international visits, newsletters and other correspondence), as well as their representations of “East” and “West,” this study reveals the conditions of and constraints on the potential for feminist solidarity across national, cultural, and religious boundaries. In addition to challenging the notion that feminism in the Middle East was “imposed” from outside, it also complicates conventional wisdom about the failure of the first-wave international women’s movement to accommodate difference. Influenced by growing ethos of cultural internationalism -

Forgotten in the Diaspora: the Palestinian Refugees in Egypt

Forgotten in the Diaspora: The Palestinian Refugees in Egypt, 1948-2011 Lubna Ahmady Abdel Aziz Yassin Middle East Studies Center (MEST) Spring, 2013 Thesis Advisor: Dr. Sherene Seikaly Thesis First Reader: Dr. Pascale Ghazaleh Thesis Second Reader: Dr. Hani Sayed 1 Table of Contents I. CHAPTER ONE: PART ONE: INTRODUCTION……………………………………………...…….4 A. PART TWO: THE RISE OF THE PALESTINIAN REFUGEE PROBLEM…………………………………………………………………………………..……………..13 B. AL-NAKBA BETWEEN MYTH AND REALITY…………………………………………………14 C. EGYPTIAN OFFICIAL RESPONSE TO THE PALESTINE CAUSE DURING THE MONARCHAL ERA………………………………………………………………………………………25 D. PALESTINE IN THE EGYPTIAN PRESS DURING THE INTERWAR PERIOD………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….38 E. THE PALESTINIAN REFUGEES IN EGYPT, 1948-1952………………………….……….41 II. CHAPTER TWO: THE NASSER ERA, 1954-1970 A. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND…………………………………………………………………….…45 B. THE EGYPTIAN-PALESTINIAN RELATIONS, 1954-1970……………..………………..49 C. PALESTINIANS AND THE NASEERIST PRESS………………………………………………..71 D. PALESTINIAN SOCIAL ORGANIZATIONS………………………………………………..…..77 E. LEGAL STATUS OF PALESTINIAN REFUGEES IN EGYPT………………………….…...81 III. CHAPTER THREE: THE SADAT ERA, 1970-1981 A. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND……………………………………………………………………….95 B. EGYPTIAN-PALESTINIAN RELATIONS DURING THE SADAT ERA…………………102 C. THE PRESS DURING THE SADAT ERA…………………………………………….……………108 D. PALESTINE IN THE EGYPTIAN PRESS DURING THE SADAT ERA……………….…122 E. THE LEGAL STATUS OF PALESTINIAN REFUGEES DURING THE SADAT ERA……………………………………………………………………………………………………….…129 IV. CHAPTER FOUR: