Genocide Against Tutsi in Rwanda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Assembly Security Council

United Nations A/70/218–S/2015/577 General Assembly Distr.: General 31 July 2015 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Seventieth session Seventieth year Item 77 of the provisional agenda* Report of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Genocide and Other Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of Rwanda and Rwandan Citizens Responsible for Genocide and Other Such Violations Committed in the Territory of Neighbouring States between 1 January and 31 December 1994 Report of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Note by the Secretary-General The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the members of the General Assembly and to the members of the Security Council the twentieth annual report of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, submitted by the President of the International Tribunal for Rwanda in accordance with article 32 of its statute (see Security Council resolution 955 (1994), annex), which states: “The President of the International Tribunal for Rwanda shall submit an annual report of the International Tribunal for Rwanda to the Security Council and to the General Assembly.” * A/70/150. 15-12744 (E) 240815 *1512744* A/70/218 S/2015/577 Letter of transmittal 31 July 2015 I have the honour to submit the twentieth annual report of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Genocide and Other Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of Rwanda and Rwandan Citizens Responsible for Genocide and Other Such Violations Committed in the Territory of Neighbouring States between 1 January and 31 December 1994, dated 31 July 2015, to the General Assembly and the Security Council, pursuant to article 32 of the statute of the International Tribunal. -

Genocide in Rwanda: the Search for Justice 15 Years On

Genocide in Rwanda: The search for justice 15 years on. An overview of the horrific 100 days of violence, the events leading to them and the ongoing search for justice after 15 years. 6 April 2009 | The Hague On the fifteenth anniversary of the plane crash killing former President Habyarimana which sparked one-hundred days of Genocide in Rwanda slaughtering over 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus, the Hague Justice Portal reflects on some of the important decisions, notable cases and remaining gaps in the ICTR’s ongoing search for justice. On 8 November 1994, seven months after the passenger plane carrying President Juvénil Habyarimana was shot out of the sky on the evening of April 6 1994 triggering Genocide in the little-known central African state of Rwanda, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 955 (1994) establishing the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). The tribunal is mandated to prosecute “persons responsible for genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law”1, with its inaugural trial commencing on January 9 1997. According to Trial Chamber I, delivering its Judgment in this first case against a suspected génocidaire, “there is no doubt that considering their undeniable scale, their systematic nature and their atrociousness” the events of the 100 days subsequent to April 6, “were aimed at exterminating the group that was targeted.”2 Indeed, given the nature and extent of the violence between April and July 1994, it is unsurprising that the ICTR has been confronted with genocide charges in nearly every case before it. Within hours of the attack on the President’s plane roadblocks had sprung up throughout Kigali and the killings began; the Hutu Power radio station, RTLM, rife with conspiracy, goading listeners with anti-Tutsi propaganda. -

Social Media and Accountability in the Cases Concerning Core Crimes

157 Social Media and Accountability in the Cases Concerning Core Crimes sWaPnil sharMa* Abstract: In these last years a dramatical increase in the use of cyber space has led to an important change also in criminal activities, emphasizing the weaknesses of actual legal frameworks in facing modern crime issues. Crime in the digital era can be more advanced due to technological in- struments, moreover the modern world assists to the exponential growth of new types of crimes such as the evolving cybercriminality. With a par- ticular regard to the Rome Statute and the International Criminal Court work, the issue which is discussed in this paper is whether the present legal structure is sufficiently efficient to deal with the problems pertai- ning to cyberspace, or whether new and updated laws and jurisprudence are needed. This research is supplemented by a case study examining the potential legal aspects of a situation where the ICC may have to deal with a case of multilayered crime. In the end, the public element of incitement is examined with reference to genocide, analyzing the effects of practical application of place factor and medium factors in the social media era. Keywords: Cybercrime, Rome Statute, International criminal justice, Ac- countability, Social Media. Table of contents: 1. Introduction. – 2. Understanding Cyber Jurisprudence. – 2.1. Deriving the Definition of Cyber Jurisprudence. – 3. Framework of International Criminal Justice System and its Efficiency in the Context of Technological Deve- lopment. – 3.1. The International Criminal Laws and the Jurisdictional Challenge. – 3.2. Jurisdiction and Article 12 of the Rome Statute. – 3.3. -

Judgement and Sentence

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Tribunal pénal international pour le Rwanda UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES ORIGINAL: ENGLISH TRIAL CHAMBER III Before: Judge Solomy Balungi Bossa, Presiding Judge Bakhtiyar Tuzmukhamedov Judge Mparany Rajohnson Registrar: Adama Dieng Date: 31 May 2012 THE PROSECUTOR v. Callixte NZABONIMANA Case No. ICTR-98-44D-T JUDGEMENT AND SENTENCE Office of the Prosecutor Defence Counsel Hassan Bubacar Jallow Vincent Courcelle-Labrousse Paul Ng’arua Philippe Larochelle Memory Maposa Simba Mawere Mary Diana Karanja Alison McFarlane Prosecutor v. Nzabonimana, Case No. ICTR-98-44D-T Table of Contents CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Overview of the Case .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Accused ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Summary of the Procedural History ............................................................................................................. 2 CHAPTER II: PRELIMINARY ISSUES .................................................................................................................. 4 2.1 Indictment .................................................................................................................................................... -

Press Clippings

SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE OUTREACH AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE The abandoned ‘thoroughfare’ of the SCSL. PRESS CLIPPINGS Enclosed are clippings of local and international press on the Special Court and related issues obtained by the Outreach and Public Affairs Office as at: Friday, 8 April 2011 Press clips are produced Monday through Friday. Any omission, comment or suggestion, please contact Martin Royston-Wright Ext 7217 2 International News Coming Back From the Brink in Sierra Leone: A Case of Selective Amnesia / Cocorioko Pages 3-4 The Psychology of War / PRNewswire Pages 5-6 ICC Judges Act on Basis of Evidence, Says ICTR spokesman / The Standard Page 7 Uhuru, Muthaura, Ali to Appear at ICC / Kenya Broadcasting Corporation Pages 8-9 International Criminal Court Judge Warns Kenyan Suspects on Incitement / United Nations Mews Page 10 Preventing Genocide Only Real Way to Honour Rwandan Victims – Ban / United Nations News Page 11 Defence of Former Minister Nzabonimana "Officially" Closed / Hirondelle News Agency Page 12 3 Cocorioko Friday, 8 April 2011 Coming back from the brink in Sierra Leone: A Case of Selective Amnesia By Karamoh Kabba Former President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah of Sierra Leone has written a beautifully bound 359-page volume entitled Coming Back from the Brink in Sierra Leone, a must read for every Sierra Leonean alive for obvious reasons. For once, President Kabbah can now be credited for modesty with words. For those who are old enough to go down memory lane with me, he had actually plunged on the jagged edge. He is phoenix – he is rising up from the ashes. -

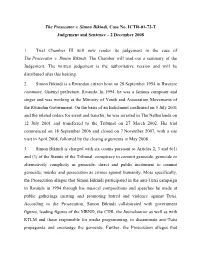

The Prosecutor V. Simon Bikindi, Case No. ICTR-01-72-T Judgement and Sentence – 2 December 2008

The Prosecutor v. Simon Bikindi, Case No. ICTR-01-72-T Judgement and Sentence – 2 December 2008 1. Trial Chamber III will now render its judgement in the case of The Prosecutor v. Simon Bikindi. The Chamber will read out a summary of the Judgement. The written judgement is the authoritative version and will be distributed after this hearing. 2. Simon Bikindi is a Rwandan citizen born on 28 September 1954 in Rwerere commune, Gisenyi prefecture, Rwanda. In 1994, he was a famous composer and singer and was working at the Ministry of Youth and Association Movements of the Rwandan Government. On the basis of an Indictment confirmed on 5 July 2001 and the related orders for arrest and transfer, he was arrested in The Netherlands on 12 July 2001 and transferred to the Tribunal on 27 March 2002. His trial commenced on 18 September 2006 and closed on 7 November 2007, with a site visit in April 2008, followed by the closing arguments in May 2008. 3. Simon Bikindi is charged with six counts pursuant to Articles 2, 3 and 6(1) and (3) of the Statute of the Tribunal: conspiracy to commit genocide; genocide or alternatively complicity in genocide; direct and public incitement to commit genocide; murder and persecution as crimes against humanity. More specifically, the Prosecution alleges that Simon Bikindi participated in the anti-Tutsi campaign in Rwanda in 1994 through his musical compositions and speeches he made at public gatherings inciting and promoting hatred and violence against Tutsi. According to the Prosecution, Simon Bikindi collaborated with government figures, leading figures of the MRND, the CDR, the Interahamwe as well as with RTLM and those responsible for media programming, to disseminate anti-Tutsi propaganda and encourage the genocide. -

THE PROSECUTOR V. Simon BIKINDI JUDGEMENT

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Tribunal pénal international pour le Rwanda UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES Original: English TRIAL CHAMBER III Before Judges: Inés Mónica Weinberg de Roca, Presiding Florence Rita Arrey Robert Fremr Registrar: Adama Dieng Judgement of: 2 December 2008 THE PROSECUTOR v. Simon BIKINDI Case No. ICTR-01-72-T JUDGEMENT Counsel for the Prosecution Counsel for the Defence William T. Egbe Andreas O’Shea Veronic Wright Jean de Dieu Momo Patrick Gabaake Peter Tafah Iain Morley Sulaiman Khan Amina Ibrahim Disengi Mugeyo The Prosecutor v. Simon Bikindi, Case No. ICTR-01-72-T TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1 1. THE TRIBUNAL AND ITS JURISDICTION ................................................................................ 1 2. THE ACCUSED ..................................................................................................................... 1 3. THE INDICTMENT ................................................................................................................ 1 4. SUMMARY OF PROCEDURAL HISTORY ................................................................................ 2 5. OVERVIEW OF THE CASE ..................................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER II: FACTUAL FINDINGS……………………………………………..…………3 1. PRELIMINARY MATTERS ..................................................................................................... -

The Role of France in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide 0 Mucyo Report

Mucyo report - The role of France in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide 0 Mucyo report- Report of an independent Commission to establish the role of France in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide. This is the full report TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS i GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1 1. Creation and historical background of the Commission 1 2. How the Commission understood its terms of reference 1 3. Methodology for the collection of information2 3.1. Sources of information in Rwanda 2 3.2. Collection of information abroad 2 3.3. Access to public documents 3 3.4. Information Processing 4 3.5. Research stages 4 INTRODUCTION TO THE REPORT 5 1. Foreign involvement in Rwanda’s conflict and in the genocide 5 1.1 Historical background 5 1.2. Recent international interventions (1990-1994) 8 1.2.1. Belgium 8 1.2.2. United States 9 1.2.3. United Nations Organisation (UNO) 10 1.2.4. An attempt at international redress? 13 1.3 Process of the recognition of the genocide 14 1.3.1 Initiatives of the United Nations Human Rights Commission 14 1.3.2 Procrastination in the recognition of the genocide in the Security Council 15 PART I: FRANCE’S INVOLVEMENT IN RWANDA BEFORE THE GENOCIDE 17 1. Historical background and legal framework of cooperation between France and Rwanda 17 1.1. Aspects of the civilian cooperation 17 1.2 Elements of military cooperation 18 1.2.1 Contents of the Special Military Assistance Agreement of 1975 18 1.2.2 Amendments of the 1975 Agreement 19 1.2.3 Increased military aid effective from 1989 20 1.3. -

ICTR, the Prosecutor V. Simon Bikindi, Judgement, 2 December 2008

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Tribunal pénal international pour le Rwanda UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES Original: English TRIAL CHAMBER III Before Judges: Inés Mónica Weinberg de Roca, Presiding Florence Rita Arrey Robert Fremr Registrar: Adama Dieng Judgement of: 2 December 2008 THE PROSECUTOR v. Simon BIKINDI Case No. ICTR-01-72-T JUDGEMENT Counsel for the Prosecution Counsel for the Defence William T. Egbe Andreas O’Shea Veronic Wright Jean de Dieu Momo Patrick Gabaake Peter Tafah Iain Morley Sulaiman Khan Amina Ibrahim Disengi Mugeyo The Prosecutor v. Simon Bikindi, Case No. ICTR-01-72-T TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1 1. THE TRIBUNAL AND ITS JURISDICTION ................................................................................ 1 2. THE ACCUSED ..................................................................................................................... 1 3. THE INDICTMENT ................................................................................................................ 1 4. SUMMARY OF PROCEDURAL HISTORY ................................................................................ 2 5. OVERVIEW OF THE CASE ..................................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER II: FACTUAL FINDINGS……………………………………………..…………3 1. PRELIMINARY MATTERS ..................................................................................................... -

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Jacqueline Niba American University Washington College of Law

Human Rights Brief Volume 21 | Issue 1 Article 11 2014 Judgment Summaries: International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Jacqueline Niba American University Washington College of Law Davina Ugochukwu American University Washington College of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/hrbrief Part of the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Niba, Jacqueline, and Davina Ugochukwu. "Judgment Summaries: International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda." Human Rights Brief 21, no. 1 (2014): 44-46. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Human Rights Brief by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Niba and Ugochukwu: Judgment Summaries: International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda JUDGMENT SUMMARIES: INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR RWANDA WAR CRIMES RESEARCH OFFICE: 1994, following the murder of Coalition stating that Ngirabatware was not present COVERAGE OF THE INTERNATIONAL pour la Défense de la République (CDR) at these locations, nor did he encourage the CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR RWANDA Chairman Martin Bucyana, Ngirabatware crowd to kill Tutsis. went to the Electrogaz and Cyanika-Gisa The Prosecutor v. Augustine Dismissing the defense’s arguments, roadblocks to address hundreds of people. Ngirabatware, Case No. -

ICTR in the Year 2011: Atrocity Crime Litigation Review for the Year 2011 Elena Baca

Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Volume 11 | Issue 3 Article 9 Summer 2013 ICTR in the Year 2011: Atrocity Crime Litigation Review for the Year 2011 Elena Baca Jessica Dwinell Chang Liu Joy McClellan Dineo Alexandra McDonald See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Elena Baca, Jessica Dwinell, Chang Liu, Joy McClellan Dineo, Alexandra McDonald, and Takeshi Yoshida, ICTR in the Year 2011: Atrocity Crime Litigation Review for the Year 2011, 11 Nw. J. Int'l Hum. Rts. 211 (2013). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol11/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Authors Elena Baca, Jessica Dwinell, Chang Liu, Joy McClellan Dineo, Alexandra McDonald, and Takeshi Yoshida This article is available in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/ njihr/vol11/iss3/9 ICTR in the Year 2011: Atrocity Crime Litigation Review in the Year 2011 Elena Baca Jessica Dwinell Chang Liu Joy McClellen Dineo Alexandra McDonald Takeshi Yoshida COMPLETION STRATEGY ¶1 As of December 7, 2011, there are five pending trial judgments and eighteen pending appeals judgments tentatively set to be completed by 2014. ¶2 This year, the Tribunal rendered judgment on the multi-party Butare case, the multi-party Bizimungu case, the multi-party Karemera case, the single-party Ndahimana case, and the single-party Gatete case. -

And Since Akayesu? the Development of Ictr Jurisprudence on Gender Crimes: a Comparison of Akayesu and Muhimana

CHENAULT MACRO FINAL 12/2/2008 6:16:36 PM AND SINCE AKAYESU? THE DEVELOPMENT OF ICTR JURISPRUDENCE ON GENDER CRIMES: A COMPARISON OF AKAYESU AND MUHIMANA SUZANNE CHENAULT∗ INTRODUCTION The first judgment of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), Prosecutor v. Jean-Paul Akayesu, heralded the legacy of the Tribunal in prosecuting crimes of sexual violence. The judgment was ground-breaking in several aspects, most significantly for articulating a conceptual definition of rape under international law and for convicting a defendant of rape as both a crime against humanity and as an instrument of genocide.1 In light of the consistent reliable evidence that sexual violations were widely and systematically perpetrated throughout Rwanda during the 1994 genocide, gender crimes prosecutions at the ICTR have thus far been inadequate. Despite the legacy of the Akayesu judgment in promoting progress in the prosecution of sexual violations in the context of mass violence and armed conflict, relatively few persons have been convicted by the ICTR for a sex-related crime.2 To date, there have been only eight ∗ Suzanne Chenault is a legal officer in the Chambers of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. Ms. Chenault is an American lawyer admitted to practice in Washington, D.C., the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and the State of California. 1. Prosecutor v. Akayesu, Case No. ICTR 96-4-T, Judgment, ¶¶ 685-95, 730-34 (Sept. 2, 1998). 2. Convictions for sexual violations, including rape, have been issued and upheld on appeal for the following four persons to date: Jean-Paul Akayesu, Laurent Semanza, Sylvestre Gacumbitsi, and Mikaeli Muhimana.