Jules Verne: Seven Novels Free

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birth in Nantes of Jules Verne, to Pierre, a Lawyer, and Sophie, of Distant Scottish Descent

A CHRONOLOGY OF J ULES V ERNE William Butcher 1828 8 February: birth in Nantes of Jules Verne, to Pierre, a lawyer, and Sophie, of distant Scottish descent. The parents have links with reactionary milieux and the slave trade. They move to 2 Quai Jean-Bart, with a magnificent view over the Loire. 1829 Birth of brother, Paul, followed by sisters Anna (1837), Mathilde (1839) and Marie (1842). 1834–7 Boarding school. The Vernes spend the summers in bucolic countryside with a buccaneer uncle, where Jules writes his travel dreams. His cousins drown in the Loire. 1837–9 École Saint-Stanislas. Performs well in geography, translation and singing. For half the year, the Vernes stay in Chantenay, overlooking the Loire. Jules’s boat sinks near an island, and he re-enacts Crusoe. Runs away to sea, but is caught by his father. 1840–2 Petit séminaire de Saint-Donitien. The family move to 6 Rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Jules writes in various genres, his father predicting a future as a ‘savant’. 1843 Collège royal de Nantes, but missing a year’s studies. 1844–6 In love with his cousin Caroline. Writes plays and short prose pieces. Easily passes baccalauréat. 1847 Studies law in the Latin Quarter. Fruitless passion for Herminie Arnault-Grossetière, dedicating her scores of poems. 1848–9 In the literary salons meets Dumas père and fils, and perhaps Victor Hugo. Law degree. 1850 Comedy ‘Broken Straws’ runs for twelve nights. 1851 Publishes short stories ‘Drama in Mexico’ and ‘Drama in the Air’. Works as private tutor, bank clerk and law clerk. -

The Sphinx of the Ice Realm Ably Well-Known Item, It Regularly Turns up in Discussions of Poe’S the Narrative of Arthur

Translating Verne runs the old Italian adage: translators are traitors. And it’s raduttore, traditore possible that no big-name author has suffered more betrayals than Frenchman TJules Verne in his nineteenth-century English translations. Fans and academics have been pointing out this problem for decades. It was in the turbulent 1960s that NYU scholar Walter James Miller made a startling discov- ery: Captain Nemo’s famed submarine, the , was manufactured from a revolutionary Nautilus type of sheet iron that was lighter than water and could float. Well, not really. Checking Verne’s French, Miller verified that the translator had sim- ply made an idiotic mistake. And then other readers started finding other kinks: the first English version of (1864) recomposed every third paragraph Journey to the Center of the Earth and gave the characters silly new monikers—Verne’s Professor Lidenbrock became Profes- sor Hardwigg. As for more literal translations, often they were preposterously abridged: in (1869) Verne includes an amusing chapter on using algebra to calculate Circling the Moon flight times—the original translator kept the chapter but left out the formulas. And then there were issues of political correctness: in (1875) Verne condemns The Mysterious Island the British Raj—his UK translator simply revamped him so that he voices support instead. In short, the Victorian translations of many Verne novels not only abound in asinine errors, they condense him, censor him, rewrite him, drop whole passages, fabricate new ones, concoct different titles, rearrange chapters, redo characterizations, chop his descriptions, dump his science, axe his jokes, and generally delete things that are politically iffy or call for homework. -

Redalyc.SCIENCE in VERNE and POE the PYM CASE

Mètode Science Studies Journal ISSN: 2174-3487 [email protected] Universitat de València España Bonet Safont, Juan Marcos SCIENCE IN VERNE AND POE THE PYM CASE Mètode Science Studies Journal, núm. 6, 2016, pp. 6-12 Universitat de València Valencia, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=511754471004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Mètode 6 MÈTODE DOCUMENT MÈTODE Science Studies Journal, 6 (2016): 6–12. University of Valencia. DOI: 10.7203/metode.85.3315 ISSN: 2174-3487. Article received: 20/02/2014, accepted: 09/07/2014. SCIENCE IN VERNE AND POE THE PYM CASE JUAN MARCOS BONET SAFONT In 1897, Jules Verne’s novel An antarctic mystery was published both in periodical form and as a complete book. It is a continuation of Edgar Allan Poe’s story The narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838). In this article, we will use the plots of both novels to show the different images of science and technology presented by the two authors. We address both Verne’s and Poe’s approach to science, as conveyed through their fictional stories. We also discuss how Verne’s scientific descriptions are much more extensive than Poe’s, a testament to Verne’s rational and learned character, as opposed to Poe’s more fantastic and imaginative approach to science. Keywords: Poe, Verne, science and literature, Pym, South Pole. -

Jules Verne. the Sphinx of the Ice Realm

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Modern Languages Faculty Publications Modern Languages 2013 Another Excellent Verne Translation Arthur B. Evans DePauw University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/mlang_facpubs Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons Recommended Citation Evans, Arthur B. "Another Excellent Verne Translation." [Review of Jules Verne's The Sphinx of the Ice Realm. Trans. and ed. Frederick Paul Walter. Albany, NY: Excelsior, 2012]. Science Fiction Studies 40.3 (2013): 572-575 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Languages Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 572 SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 40 (2013) BOOKS IN REVIEW Another Excellent Verne Translation. Jules Verne. The Sphinx of the Ice Realm: The First Complete English Translation, with the Full Text of The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym by Edgar Allan Poe. Trans. and ed. Frederick Paul Walter. Albany: State U of New York P/Excelsior, 2012. xix + 413 pp. $24.95 pbk. The past couple of decades have witnessed a resurgence of interest in Jules Verne and the appearance of a host of new English translations of his legendary Voyages Extraordinaires. For example, Oxford University Press’s “World’s Classics” series has published several fine translations by William Butcher, including Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864) in 1992, Around the World in 80 Days (1873) in 1995, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas (1870) in 1998, and The Adventures of Captain Hatteras (1866) in 2005. -

Jules Verne Studies – Etudes Jules Verne Vol

V E R N I A N A Jules Verne Studies – Etudes Jules Verne Vol. 2 2009–2010 Initial capital “V” copyright ©1972 Richard Aeschlimann, Yverdon- les-Bains (Switzerland). Reproduced with his permission. La lettrine “V” de couverture est copyright ©1972 Richard Aeschlimann, Yverdon-les-Bains (Suisse). Elle est reproduite ici avec son autorisation. V E R N I A N A Jules Verne Studies – Etudes Jules Verne Vol. 2 2009–2010 ISSN : 1565-8872 Editorial Board – Comité de rédaction William Butcher ([email protected] and http://www.ibiblio.org/julesverne) has taught at the École nationale d’administration, researched at the École normale supérieure and Oxford, and is now a Hong Kong property developer. His publications since 1980, notably for Macmillan, St Martin’s and Gallimard, include Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Self, Jules Verne: The Definitive Biography and Salon de 1857. In addition to a series of Verne novels for OUP, he has recently published a critical edition of Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours. Daniel Compère ([email protected]) est professeur de littérature française à l’Université de Paris III-Sorbonne nouvelle. Créateur du Centre Jules Verne d’Amiens en 1972, il a publié de nombreux ouvrages et articles sur Jules Verne (dont Les Voyages extraordinaires de Jules Verne. Pocket, 2005). Président de l’Association des Amis du Roman populaire et responsable de la revue Le Rocambole, il a également consacré des publications à la littérature populaire dont deux livres sur Alexandre Dumas (dont D’Artagnan & Cie. Les Belles Lettres - Encrage, 2002). -

20,000 Leagues Under The

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea December 23, 1954 Copyright © 2017 - AllEars.net - Created by JamesD (dzneynut) Email the bonus clue to [email protected] for a chance to win a Disney pin! 1 P A 2 3 4 5 B U R B A N K T S 6 7 8 L I W A R S H I P S 9 G O L D E N A R R O W O E 10 11 U K H I S T A T O O K D A U E 12 R A O L N R 13 14 15 C O N S E I L U E K L I N C O L N 16 R Y G O J O 17 18 F A L S E L F A R 19 20 P E S M E R A L D A M R F 21 A A S T R U E E L 22 N E M O A S E 23 D O J L M I 24 25 G I A N T S Q U I D E A F I R S T S L S A C 26 T E A O N H 27 28 E D E S T R O Y I N A B O T T L E 29 R V O P A R 30 E N N A U T I L U S R N R I 31 V U L C A N I A I A E X S Kirk Douglas Esmeralda Nemo James Mason Vulcania Nautilus Lincoln Fleischer two False True Golden Arrow Aronnax A Whale of a Tale his tatoo Fantasia Rorapandi Conseil in a bottle eyes giant squid Peter Lorre Burbank warships Jules Verne shot destroy sea monster sunk Paul Lukas Paris first ̣ The organ played by Captain Nemo in this film eventually found its way into what popular Disneyland attraction? [HAUNTEDMANSION] Across Down 2. -

Lewintro.Pdf

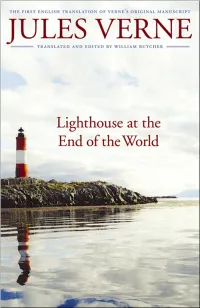

7>HDC;GDCI>:GHD;>B6<>C6I>DC JULES VERNE Lighthouse at the End of theWorld Le Phare du bout du monde The First English Translation of Verne’s Original Manuscript Translated and edited by William Butcher JC>K:GH>IND;C:7G6H@6EG:HH•A>C8DAC Publication of this book was made possible by a grant from The Florence Gould Foundation. Le Phare du bout du monde © Les Éditions internationales Alain Stanké, 1999. © Editions de l’Archipel. Translation and critical apparatus © 2007 by William Butcher. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Verne, Jules, 1828–1905. [Le phare du bout du monde. English] Lighthouse at the end of the world = Le phare du bout du monde : the first English translation of Verne’s original manuscript / Jules Verne ; translated and edited by William Butcher. p. cm. — (Bison frontiers of imagination) Includes bibliographical references. isbn-13: 978-0-8032-4676-8 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-13: 978-0-8032-6007-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) I. Butcher, William, 1951– II. Title. III. Title: Le phare du bout du monde. pq2469.p4e5 2007 843'.8—dc22 2007001717 Set in Adobe Garamond by Kim Essman. Designed by R. W. Boeche. contents Introduction vii A Chronology of Jules Verne xxxiii Map of Staten Island xxxix 1.Inauguration 1 2. Staten Island 10 3. The Three Keepers 19 4.Kongre's Gang 30 5. The Schooner Maule 41 6. At Elgor Bay 50 7.The Cavern 61 8. Repairing the Maule 70 9.Vasquez 79 10.After the Wreck 89 11.The Wreckers 99 12. -

![Jules Verne: the Extraordinary Voyages Collection [Free Audiobook Links Included] Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5654/jules-verne-the-extraordinary-voyages-collection-free-audiobook-links-included-online-7735654.webp)

Jules Verne: the Extraordinary Voyages Collection [Free Audiobook Links Included] Online

YGArF (Free pdf) Jules Verne: The Extraordinary Voyages Collection [Free Audiobook Links Included] Online [YGArF.ebook] Jules Verne: The Extraordinary Voyages Collection [Free Audiobook Links Included] Pdf Free Jules Verne *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #711761 in eBooks 2017-05-24 2017-05-24File Name: B071LQG48X | File size: 72.Mb Jules Verne : Jules Verne: The Extraordinary Voyages Collection [Free Audiobook Links Included] before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Jules Verne: The Extraordinary Voyages Collection [Free Audiobook Links Included]: This ebook comprises the 54 volumes of the Extraordinary Voyages cycle by Jules Verne. (Important note: due to copyright restrictions, novels marked with a (*) are offered in their original French)For a better reading experience, we have created active tables of contents at the beginning of each volume as well as a master table of contents. Clicking on a volume or a chapter title will take you to the parent table of contents.CONTENTS:1.Five weeks in a balloon, or, journeys and discoveries in Africa by three Englishmen2.The adventures of Captain Hatteras3.A journey into the center of the Earth4.From the Earth to the Moon5.In search of the castaways6.20,000 leagues under the sea7.Around the Moon8.A floating city9.The adventures of three Englishmen and three Russians in South Africa10.The fur country11.Around the world in eighty days12.The mysterious island13.The survivors of the -

Contents 2. Prefaces to the Mysterious Island, Two

Contents Introduction Note on Previous Translations A Chronology of Jules Verne 1. Inception of the Novel A. The Manuscripts of “Uncle Robinson” B. The Manuscripts of The Mysterious Island C. Publication of The Mysterious Island 2. Prefaces to The Mysterious Island, Two Years Vacation, and Second Home- land A. A Few Words to the Readers of The Mysterious Island B. Preface to Two Years Vacation C. Preface – Why I Wrote Second Homeland 3. Select Bibliography A. Principal Works of Verne Cited B. Studies of The Mysterious Island C. Books on Verne D. The Principal Origins of The Mysterious Island The Mysterious Island List of Abbreviations Appendix A: The Sources of The Mysterious Island Appendix B: Verne’s Other Writing on the Desert-Island Theme 1 Introduction At a time when Jules Verne is making a comeback in the United States as a main- stream literary figure, one of his most brilliant and famous novels remains unavailable in English. Although half a dozen works carrying the title “The Mysterious Island” are in print, all follow W. H. G. Kingston’s 1874-75 translation, which omits sections of the novel and ideologically skews other passages.1 The real Mysterious Island is nearly 200,000 words long. For Sidney Kravitz, this first-ever complete translation has been a long labor of love, resulting in a highly accurate text which captures every nuance and will be the undisputed reference text in English. L’Ile mystérieuse (MI – 1874) needs little presentation. In 1865 during the American Civil War, a violent storm sweeps a balloon carrying a group of Unionists to an island in the Pacific. -

Jules Verne's English Translations: a Bibliography

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Modern Languages Faculty publications Modern Languages 3-2005 Jules Verne's English Translations: A Bibliography Arthur B. Evans DePauw University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.depauw.edu/mlang_facpubs Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Arthur B. Evans. "Jules Verne's English Translations: A Bibliography" Science Fiction Studies 32.1 (2005): 105-141. Available at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/mlang_facpubs/15/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Languages Faculty publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DePauw University From the SelectedWorks of Arthur Bruce Evans March 2005 Jules Verne's English Translations: A Bibliography Contact Start Your Own Notify Me Author SelectedWorks of New Work Available at: http://works.bepress.com/arthur_evans/11 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF VERNE’S ENGLISH TRANSLATIONS 105 Arthur B. Evans A Bibliography of Jules Verne’s English Translations The following bibliography lists the most common English translations of Jules Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaires. The opening passages from Verne’s original French texts and their different English translations are provided for purposes of identification and comparison. For those novels originally published in two or three parts (where, in translation, each part was often published as a separate volume), the opening passage for each part is indicated by the symbol [N]. -

Around the World in Eighty Days Verne, Jules

Around the World in Eighty Days Verne, Jules Published: 1872 Categorie(s): Fiction, Action & Adventure Source: http://en.wikisource.org 1 About Verne: Jules Gabriel Verne (February 8, 1828–March 24, 1905) was a French author who pioneered the science-fiction genre. He is best known for novels such as Journey To The Center Of The Earth (1864), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea (1870), and Around the World in Eighty Days (1873). Verne wrote about space, air, and underwater travel before air travel and practical submarines were invented, and before practical means of space travel had been devised. He is the third most translated author in the world, according to Index Transla- tionum. Some of his books have been made into films. Verne, along with Hugo Gernsback and H. G. Wells, is often popularly referred to as the "Father of Science Fiction". Source: Wikipedia Also available on Feedbooks for Verne: • 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1870) • In the Year 2889 (1889) • A Journey into the Center of the Earth (1877) • The Mysterious Island (1874) • From the Earth to the Moon (1865) • An Antarctic Mystery (1899) • The Master of the World (1904) • Off on a Comet (1911) • The Underground City (1877) • Michael Strogoff, or The Courier of the Czar (1874) Note: This book is brought to you by Feedbooks http://www.feedbooks.com Strictly for personal use, do not use this file for commercial purposes. 2 Chapter 1 IN WHICH PHILEAS FOGG AND PASSEPARTOUT ACCEPT EACH OTHER, THE ONE AS MASTER, THE OTHER AS MAN Mr. Phileas Fogg lived, in 1872, at No. -

Ethnicity and Crosscultural Imaging in Jules Verne's La Jangada

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University World Languages and Cultures Faculty Publications Department of World Languages and Cultures 2008 Along the Banks of the Amazon: Ethnicity and Crosscultural Imaging in Jules Verne's La Jangada Rudyard Alcocer [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/mcl_facpub Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, Latin American History Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Alcocer, R. (2008). Along the banks of the Amazon: Ethnicity and crosscultural imaging in Jules Verne's La Jangada. Reconsidering Comparative Literary Studies, 5(1), 1-17. Available at: http://ejournals.library.vanderbilt.edu/index.php/ameriquests/article/view/112 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of World Languages and Cultures at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages and Cultures Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Along the Banks of the Amazon: Ethnicity and Crosscultural Imaging in Jules Verne’s La Jangada Rudyard Alcocer In what ways can a lesser-known novel by a prominent 19th-century French writer have any bearing on contemporary discussions of colonial and post-colonial ideologies in Latin America? Jules Verne (1828-1905) remains well known, especially in science fiction circles, on account of his narratives about extraordinary voyages, narratives that have held nearly the entire globe and the heavens alike as an artistic canvas. As such, in his writings he often blurred the line that separates the known world from the unknown.